A Nukuoro Origin Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARC Code List for Countries: Part I

Code Sequence PART II: CODE SEQUENCE Discontinued codes are identified by a hyphen preceding the code aa Albania ce Sri Lanka abc Alberta cf Congo (Brazzaville) -ac Ashmore and Cartier Islands cg Congo (Democratic Republic) ae Algeria ch China (Republic : 1949- ) af Afghanistan ci Croatia ag Argentina cj Cayman Islands -ai Anguilla ck Colombia ai Armenia (Republic) cl Chile -air Armenian S.S.R. cm Cameroon aj Azerbaijan -cn Canada -ajr Azerbaijan S.S.R. cou Colorado aku Alaska -cp Canton and Enderbury Islands alu Alabama cq Comoros am Anguilla cr Costa Rica an Andorra -cs Czechoslovakia ao Angola ctu Connecticut aq Antigua and Barbuda cu Cuba aru Arkansas cv Cape Verde as American Samoa cw Cook Islands at Australia cx Central African Republic au Austria cy Cyprus aw Aruba -cz Canal Zone ay Antarctica dcu District of Columbia azu Arizona deu Delaware ba Bahrain dk Denmark bb Barbados dm Benin bcc British Columbia dq Dominica bd Burundi dr Dominican Republic be Belgium ea Eritrea bf Bahamas ec Ecuador bg Bangladesh eg Equatorial Guinea bh Belize em East Timor bi British Indian Ocean Territory enk England bl Brazil er Estonia bm Bermuda Islands -err Estonia bn Bosnia and Hercegovina es El Salvador bo Bolivia et Ethiopia bp Solomon Islands fa Faroe Islands br Burma fg French Guiana bs Botswana fi Finland bt Bhutan fj Fiji bu Bulgaria fk Falkland Islands bv Bouvet Island flu Florida bw Belarus fm Micronesia (Federated States) -bwr Byelorussian S.S.R. fp French Polynesia bx Brunei fr France cau California fs Terres australes et antarctiques cb Cambodia françaises cc China ft Djibouti cd Chad gau Georgia MARC Code List for Countries page 37 Code Sequence gb Kiribati kz Kazakhstan gd Grenada -kzr Kazakh S.S.R. -

Ethnography of Ontong Java and Tasman Islands with Remarks Re: the Marqueen and Abgarris Islands

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 9, No. 3 July 1986 ETHNOGRAPHY OF ONTONG JAVA AND TASMAN ISLANDS WITH REMARKS RE: THE MARQUEEN AND ABGARRIS ISLANDS by R. Parkinson Translated by Rose S. Hartmann, M.D. Introduced and Annotated by Richard Feinberg Kent State University INTRODUCTION The Polynesian outliers for years have held a special place in Oceanic studies. They have figured prominently in discussions of Polynesian set- tlement from Thilenius (1902), Churchill (1911), and Rivers (1914) to Bayard (1976) and Kirch and Yen (1982). Scattered strategically through territory generally regarded as either Melanesian or Microne- sian, they illustrate to varying degrees a merging of elements from the three great Oceanic culture areas—thus potentially illuminating pro- cesses of cultural diffusion. And as small bits of land, remote from urban and administrative centers, they have only relatively recently experienced the sustained European contact that many decades earlier wreaked havoc with most islands of the “Polynesian Triangle.” The last of these characteristics has made the outliers particularly attractive to scholars interested in glimpsing Polynesian cultures and societies that have been but minimally influenced by Western ideas and Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 1 2 Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 accoutrements. For example, Tikopia and Anuta in the eastern Solo- mons are exceptional in having maintained their traditional social structures, including their hereditary chieftainships, almost entirely intact. And Papua New Guinea’s three Polynesian outliers—Nukuria, Nukumanu, and Takuu—may be the only Polynesian islands that still systematically prohibit Christian missionary activities while proudly maintaining important elements of their old religions. -

The Paleoecology and Fire History from Crater Lake

THE PALEOECOLOGY AND FIRE HISTORY FROM CRATER LAKE, COLORADO: THE LAST 1000 YEARS By Charles T. Mogen A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science and Policy Northern Arizona University August 2018 Approved: R. Scott Anderson, Ph.D., Chair Nicholas P. McKay, Ph.D. Darrell S. Kaufman, Ph.D. Abstract High-resolution pollen, plant macrofossil, charcoal and pyrogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) records were developed from a 154 cm long sediment core collected from Crater Lake (37.39°N, 106.70°W; 3328 m asl), San Juan Mountains, Colorado. Several studies have explored Holocene paleo-vegetation and fire histories from mixed conifer and subalpine bogs and lakes in the San Juan and southern Rocky Mountains utilizing both palynological and charcoal studies, but most have been at relatively low resolution. In addition to presenting the highest resolution palynological study over the last 1000 years from the southern Rocky Mountains, this thesis also presents the first high-resolution pyrogenic PAH and charcoal paired analysis aimed at understanding both long-term fire history and the unresolved relationship between how each of these proxies depict paleofire events. Pollen assemblages, pollen ratios, and paleofire activity, indicated by charcoal and pyrogenic PAH records, were used to infer past climatic conditions. Although the ecosystem surrounding Crater Lake has remained a largely spruce (Picea) dominated forest, the proxies developed in this thesis suggest there were two distinct climate intervals between ~1035 to ~1350 CE and ~1350 to ~1850 CE in the southern Rocky Mountains, associated with the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA) and Little Ice Age (LIA) respectively. -

Micronesica 37(1) Final

Micronesica 37(1):163-166, 2004 A Record of Perochirus cf. scutellatus (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands GARY J. WILES1 Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, 192 Dairy Road, Mangilao, Guam 96913, USA Abstract—This paper documents the occurrence of the gecko Perochirus cf. scutellatus at Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands, where it is possibly restricted to a single islet. This represents just the third known location for the species and extends its range by 975 km. Information gathered to date suggests the species was once more widespread and is perhaps sensitive to human-induced habitat change. The genus Perochirus is comprised of three extant species of gecko native to Micronesia and Vanuatu and an extinct form from Tonga (Brown 1976, Pregill 1993, Crombie & Pregill 1999). The giant Micronesian gecko (P. scutellatus) is the largest member of the genus and was until recently considered endemic to Kapingamarangi Atoll in southern Micronesia, where it is common on many islets (Buden 1998a, 1998b). Crombie & Pregill (1999) reported two specimens resem- bling this species from Fana in the Southwest Islands of Palau; these are consid- ered to be P. cf. scutellatus pending further comparison with material from Kapingamarangi (R. Crombie, pers. comm.). Herein, I document the occurrence of P. cf. scutellatus from an additional site in Micronesia. During a week-long fruit bat survey at Ulithi Atoll in Yap State, Caroline Islands in March 1986 (Wiles et al. 1991), 14 of the atoll’s larger islets com- prising 77% of the total land area were visited. Fieldwork was conducted pri- marily from dawn to dusk, with four observers spending much of their time walking transects through the forested interior of each islet. -

The CANADIAN FIELD-NATURALIST

The CANADIAN FIELD-NATURALIST Published by THE OTTAWA FIELD-NATURALISTS’ CLUB, Ottawa Canada Linda J. Gormezano © A black and white version of this photo appears on the cover of Volume 122, Number 4 (Oct–Dec 2008) of the Journal and is referred to in the text of Rockwell, Gormezano and Hedman 122:323-326. Grizzly Bears, Ursus arctos, in Wapusk National Park, Northeastern Manitoba ROBERT ROCKWELL 1,3 , L INDA GORMEZANO 1, and DARYLL HEDMAN 2 1Division of Vertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79 th Street, New York, New York 10024 USA 2Manitoba Conservation, Thompson, Manitoba R8N 1X4 Canada 3Corresponding author: Robert Rockwell e-mail: [email protected] Rockwell, Robert, Linda Gormezano, and Daryll Hedman. 2008. Grizzly Bears, Ursus arctos, in Wapusk National Park, northeastern Manitoba. Canadian Field-Naturalist 122(4): 323-326. We report on nine sightings of Grizzly Bears ( Ursus arctos ) in northeastern Manitoba in what is now Wapusk National Park. Although biological research in the region has been conducted regularly since 1965, all sightings have been made since 1996. The Grizzly Bears were seen either along rivers known to harbor fish or in an area known for berries . Key Words: Grizzly Bear, Ursus arctos , Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada. Grizzly Bears ( Ursus arctos ) are reported to have been absent from Manitoba historically at least through 1989 (Banfield 1959, 1974; Harington et al. 1962; Banci 1991, McLellan And Bianci 1999). Some recent accounts and range maps have included Manitoba in the Grizzly Bear’s regular range (e.g., Schwartz et al. 2003), while others indicate that the regular range ends north of the Manitoba border but list rare, extra-limital observations for at least two sites along the Hudson Bay coast of Manitoba (e.g., Ross 2002*). -

Jg U O F N'.Tio:;

J GUOF N'.TIO:;, C. 121,1.:, 44.12 34/711. Communicated to the Council and Members Geneva ; inarch 17th. 19 34. of the League. SAAR E^STN. PETITION FROM IHE "SAARL.iNPISCHE WI RT5C1IAFTSYE RE INI GUNG” . Note by the Secretary-Genera 1, The Secretary-General has the honour to circulate for the information of the Council and Members of the League a letter from the Chair : .an of the Governing Com mission of the Saar Territory, dated March Oth, 1934, enclosing a petition from the Saarl&ndische Wirtschafts- vereinigung", dated February 19th, 1934. Translation) Saarbruck, March 8th, 1934. To the Secretary-General of the League of Nations. Sir, I have the honour to send you herewith a petition, dated February 19th, 1934, addressed to the Council of the League of Nations by the Saar Economic Association ( :,Saarl9ndische Wirtschaftavereinigung”) „ The Governing Commission, referring to its last periodi cal report and to the special reports submitted by it to the Council in January 1934, considers that the measures concerning the allocation of meeting-halls, licensed premises, etc . seem to come vri thin the province of the Plebiscite Co emission which is to be appointed by the Council. I have the honour to be, etc., (Signed) G. G. KNOX, 2 - nslation from G-êrrrrn j SAAR ECONOMIC AS SC 01, TION Saarlouis, February 19th, 1934 The undersigned Committee of the Saar iicononic Associa tion, Saarlouis, has the honour to acquaint the League of Nations with the following : The League of Nations has devoted special attention to the question of the plebiscite in the Saar Territory and has appointed a sps cial Commission for this purpose. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

KAY, Paul, and Chad K. Mcdaniel, the Linguistic Significance of the Meanings of Basic Color Language,Terms

7 8 Cecil H. Brown KAY, Paul, and Chad K. McDANIEL, The Linguistic Significance of the Meanings of Basic Color Language,Terms. 54:610-46. KEMPTON, Willett, 1978. Category Grading and Taxonomic Relations: a Mug Is a Sort ofAmerican Cup. Ethnologist, 5:44-65. ----------- , 1981. The Folk Classification of Ceramics: a Study of Cognitive Prototypes. New York, Academic Press. LAKOFF, George, 1987.Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about theChicago Mind. University Press. RANDALL, Robert A., 1977. Change and Variation in Samal Fishing: Making Plans to “Make a Living” in the Southern Philippines. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. ----------- , and Eugene S. HUNN, 1984. Do Life-forms Evolve or do Uses for Life? Some Doubts about Brown’s Universals Hypotheses.American Ethnologist, 11:329-49. ROSCH, Eleanor, 1975. Universals and Cultural Specifics in Human Categorization, in R.W. Brislin, S. Bochner, and W.J. Lonner (eds),Cross-cultural Perspectives on Learning: the Interface between Culture and Learning. New York, Halsted Press, pp. 177-206. ----------- , 1977. Human Categorization, in N. Warren (ed.),Studies in Cross-cultural Psychology, vol.l. New York, Academic Press, pp. 1-49. ----------- , and Carolyn B. MERVIS, 1975. Family Resemblances: Studies in the Internal Structure of Categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7:573-605. WIERZBICKA, Anna, 1985.Lexicography and Conceptual Analysis. Ann Arbor, Karoma. WITKOWSKI, Stanley R., Cecil H. BROWN, and P. CHASE, 1981. Where do Tree Terms Come from?Man, (n.s.) 16:1-14. FINGOTA/FANGOTA: SHELLFISH AND FISHING IN POLYNESIA Ross Clark University of Auckland A few years ago, in the course of a brief foray into the shallows of marine ethnotaxonomy (Clark 1981),11 suggested the possibility of “shellfish” as a labelled life-form category in some Polynesian languages. -

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH AMONG MICRONESIANS Behavioral Health Teleecho Clinic

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH AMONG MICRONESIANS Behavioral Health TeleECHO Clinic August 20, 2019 Davis Rehuher, BA1, Earl S. Hishinuma, PhD1, Keisha Willis, BS1, & Sidney Roberts, BS1 Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54MD007601 1Department of Psychiatry, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa OBJECTIVES BACKGROUND MENTAL CULTURAL AND CONTEXT HEALTH ASPECTS Micronesia In the Micronesian Cultural Geography region considerations Political Status Among migrants in Resources the US Interests Implications and Indicators Recommendations Migration MICRONESIA, MELANESIA, POLYNESIA MICRONESIA FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA UNITED STATES AFFILIATED PACIFIC ISLANDS - MICRONESIA US Territories COFA Nations THE MICRONESIAN REGION Selected Selected Indigenous Indigenous Area Political Status Citizenship Populations Languages Guam Unincorporated Territory US Chamorro Chamorro Commonwealth Chamorro Chamorro N. Mariana Islands US Territory Carolinian Carolinian F. S. Micronesia Freely Associated State FSM Chuukese Chuukese Chuuk State FSM State FSM Carolinian Carolinian Kosrae State FSM State FSM Kosraen Kosraen Pohnpeian Pohnpeian Pohnpei State FSM State FSM Nukuoro Nukuoro Kapingamarangi Kapingamarangi Yapese Yapese Yap State FSM State FSM Ulithian Ulithian Marshall Islands Freely Associated State Marshall Islands Marshallese Marshallese Palau Freely Associated State Palauan Palauan Palauan GUAM -

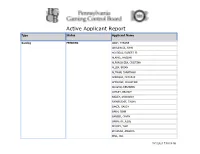

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

Cedar Breaks National Monument NRCA

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Cedar Breaks National Monument Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR—2018/1631 ON THIS PAGE Markagunt Penstemon. Photo Credit: NPS ON THE COVER Clouds over Red Rock. Photo Credit:© Rob Whitmore Cedar Breaks National Monument Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR—2018/1631 Author Name(s) Lisa Baril, Kimberly Struthers, and Patricia Valentine-Darby Utah State University Department of Environment and Society Logan, Utah Editing and Design Kimberly Struthers May 2018 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Continuing Evolution of H6N2 Influenza a Virus in South African

Abolnik et al. BMC Veterinary Research (2019) 15:455 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2210-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Continuing evolution of H6N2 influenza a virus in South African chickens and the implications for diagnosis and control Celia Abolnik1* , Christine Strydom2, Dionne Linda Rauff2, Daniel Barend Rudolph Wandrag1 and Deryn Petty3 Abstract Background: The threat of poultry-origin H6 avian influenza viruses to human health emphasizes the importance of monitoring their evolution. South Africa’s H6N2 epidemic in chickens began in 2001 and two co-circulating antigenic sub-lineages of H6N2 could be distinguished from the outset. The true incidence and prevalence of H6N2 in the country has been difficult to determine, partly due to the continued use of an inactivated whole virus H6N2 vaccine and the inability to distinguish vaccinated from non-vaccinated birds on serology tests. In the present study, the complete genomes of 12 H6N2 viruses isolated from various farming systems between September 2015 and February 2019 in three major chicken-producing regions were analysed and a serological experiment was used to demonstrate the effects of antigenic mismatch in diagnostic tests. Results: Genetic drift in H6N2 continued and antigenic diversity in sub-lineage I is increasing; no sub-lineage II viruses were detected. Reassortment patterns indicated epidemiological connections between provinces as well as different farming systems, but there was no reassortment with wild bird or ostrich influenza viruses. The sequence mismatch between the official antigens used for routine hemagglutination inhibition (HI) testing and circulating field strains has increased steadily, and we demonstrated that H6N2 field infections are likely to be missed.