Interactive Lesson Guide™ for Astronomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathématiques Et Espace

Atelier disciplinaire AD 5 Mathématiques et Espace Anne-Cécile DHERS, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Peggy THILLET, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Yann BARSAMIAN, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Olivier BONNETON, Sciences - U (mathématiques) Cahier d'activités Activité 1 : L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL Activité 2 : DENOMBREMENT D'ETOILES DANS LE CIEL ET L'UNIVERS Activité 3 : D'HIPPARCOS A BENFORD Activité 4 : OBSERVATION STATISTIQUE DES CRATERES LUNAIRES Activité 5 : DIAMETRE DES CRATERES D'IMPACT Activité 6 : LOI DE TITIUS-BODE Activité 7 : MODELISER UNE CONSTELLATION EN 3D Crédits photo : NASA / CNES L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL (3 ème / 2 nde ) __________________________________________________ OBJECTIF : Détermination de la ligne d'horizon à une altitude donnée. COMPETENCES : ● Utilisation du théorème de Pythagore ● Utilisation de Google Earth pour évaluer des distances à vol d'oiseau ● Recherche personnelle de données REALISATION : Il s'agit ici de mettre en application le théorème de Pythagore mais avec une vision terrestre dans un premier temps suite à un questionnement de l'élève puis dans un second temps de réutiliser la même démarche dans le cadre spatial de la visibilité d'un satellite. Fiche élève ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Victor Hugo a écrit dans Les Châtiments : "Les horizons aux horizons succèdent […] : on avance toujours, on n’arrive jamais ". Face à la mer, vous voyez l'horizon à perte de vue. Mais "est-ce loin, l'horizon ?". D'après toi, jusqu'à quelle distance peux-tu voir si le temps est clair ? Réponse 1 : " Sans instrument, je peux voir jusqu'à .................. km " Réponse 2 : " Avec une paire de jumelles, je peux voir jusqu'à ............... km " 2. Nous allons maintenant calculer à l'aide du théorème de Pythagore la ligne d'horizon pour une hauteur H donnée. -

The Brightest Stars Seite 1 Von 9

The Brightest Stars Seite 1 von 9 The Brightest Stars This is a list of the 300 brightest stars made using data from the Hipparcos catalogue. The stellar distances are only fairly accurate for stars well within 1000 light years. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 No. Star Names Equatorial Galactic Spectral Vis Abs Prllx Err Dist Coordinates Coordinates Type Mag Mag ly RA Dec l° b° 1. Alpha Canis Majoris Sirius 06 45 -16.7 227.2 -8.9 A1V -1.44 1.45 379.21 1.58 9 2. Alpha Carinae Canopus 06 24 -52.7 261.2 -25.3 F0Ib -0.62 -5.53 10.43 0.53 310 3. Alpha Centauri Rigil Kentaurus 14 40 -60.8 315.8 -0.7 G2V+K1V -0.27 4.08 742.12 1.40 4 4. Alpha Boötis Arcturus 14 16 +19.2 15.2 +69.0 K2III -0.05 -0.31 88.85 0.74 37 5. Alpha Lyrae Vega 18 37 +38.8 67.5 +19.2 A0V 0.03 0.58 128.93 0.55 25 6. Alpha Aurigae Capella 05 17 +46.0 162.6 +4.6 G5III+G0III 0.08 -0.48 77.29 0.89 42 7. Beta Orionis Rigel 05 15 -8.2 209.3 -25.1 B8Ia 0.18 -6.69 4.22 0.81 770 8. Alpha Canis Minoris Procyon 07 39 +5.2 213.7 +13.0 F5IV-V 0.40 2.68 285.93 0.88 11 9. Alpha Eridani Achernar 01 38 -57.2 290.7 -58.8 B3V 0.45 -2.77 22.68 0.57 144 10. -

Ov\,E <1000{ Tayget

oV\,e <1000{ TaYget w~tVi SOVlA.e otViey s~gVits wortVt see~v\'g wVi~Le You'ye ~v\, tVie Ne~gVtboYVioofi MlAycltl GLustey M4g wLtVi ~cn'bov\" stClr X CClv\"~rL Cl V\.,c{ Cl v\"L~e grou-p of stClYS Cl rouV\.,c{ "B>etCl CCl V\.,Ls M~v\"orLs Cluster M48, a magnitude 5.5 open star cluster in the constellation Hydra, was first discovered by comet-hunter Charles Messier in 1771 but, because Messier misstated its coordinates, it was "lost" until 1934, when German astronomer Oswalt Thomas demonstrated that the cluster Messier described was NGC 2458. The cluster is shown slightly right of center near the bottom of the chart, along with other nearby stars that we will use in this month's hunt: • Pollux • • • • • • Gamma M44 • Cancer. • • ~ • ;. I • ·HYdra~ Procyon •• • Sextans • • Monoceros • 0 ~\ • M48 . To find M48 using binoculars or a finderscope, start at Procyon, the bright mag 0.3 star at the SE corner of The Winter Hexagon. Procyon is the 8th brightest star in the sky, and quite close to us, at a distance of only 11~ light years. It was named Procyon, meaning "Before the Dog," because it rises just before Sirius, The Dog Star: that was important because Sirius heralded the annual flooding of the Nile River, which was crucial to the life of ancient Egypt. Just over 4° NW of Procyon is mag 2.9 blue dwarf Beta Canis Minoris, which forms a pretty lYz ° binocular group with a mag 4.3 orange giant and a mag 5.0 yellow giant. -

GTO Keypad Manual, V5.001

ASTRO-PHYSICS GTO KEYPAD Version v5.xxx Please read the manual even if you are familiar with previous keypad versions Flash RAM Updates Keypad Java updates can be accomplished through the Internet. Check our web site www.astro-physics.com/software-updates/ November 11, 2020 ASTRO-PHYSICS KEYPAD MANUAL FOR MACH2GTO Version 5.xxx November 11, 2020 ABOUT THIS MANUAL 4 REQUIREMENTS 5 What Mount Control Box Do I Need? 5 Can I Upgrade My Present Keypad? 5 GTO KEYPAD 6 Layout and Buttons of the Keypad 6 Vacuum Fluorescent Display 6 N-S-E-W Directional Buttons 6 STOP Button 6 <PREV and NEXT> Buttons 7 Number Buttons 7 GOTO Button 7 ± Button 7 MENU / ESC Button 7 RECAL and NEXT> Buttons Pressed Simultaneously 7 ENT Button 7 Retractable Hanger 7 Keypad Protector 8 Keypad Care and Warranty 8 Warranty 8 Keypad Battery for 512K Memory Boards 8 Cleaning Red Keypad Display 8 Temperature Ratings 8 Environmental Recommendation 8 GETTING STARTED – DO THIS AT HOME, IF POSSIBLE 9 Set Up your Mount and Cable Connections 9 Gather Basic Information 9 Enter Your Location, Time and Date 9 Set Up Your Mount in the Field 10 Polar Alignment 10 Mach2GTO Daytime Alignment Routine 10 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR NEW SETUPS OR SETUP IN NEW LOCATION 11 Assemble Your Mount 11 Startup Sequence 11 Location 11 Select Existing Location 11 Set Up New Location 11 Date and Time 12 Additional Information 12 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR MOUNTS USED AT THE SAME LOCATION WITHOUT A COMPUTER 13 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR COMPUTER CONTROLLED MOUNTS 14 1 OBJECTS MENU – HAVE SOME FUN! -

Campus Connection March 2017.Indd

SPONSORED CONTENT CAMPUS CONNECTION toledoBlade.com THE BLADE, TOLEDO, OHIO ■ MARCH 8, 2017 SECTION B PAGE 9 GET MORE @ toledoblade.com/campusconnection Your source for higher education news and information. UT Undergrad Discovers Mercy College Working to Elusive Companion Star Respond to Strong Local to Beta Canis Minoris Demand for Paramedics Nick Dulaney was Beta Canis Minoris,” to determine how the Emergency Medical 33 percent from 2010 and lifesaving skills. determined to solve a Dulaney said. “While stars interact. Technicians (EMT) and to 2020, much faster Part of the Paramedic galactic mystery. Why it’s circling the bright Dulaney is the lead Paramedics represent than the average for certifi cate program is there an unexpected, star, the smaller star author on the research the fi rst responders in all occupations.” In the provides students a wavy edge on a disk stops the disk on the paper recently pub- emergency medical sit- northwest Ohio area clinical rotation with around a bright, rapidly bigger star from getting lished in the Astrophys- uations. They are often EMTs and Paramedics hands-on experience rotating star located too big by creating a ical Journal. He worked the fi rst at the scene are in high demand. with area fi rst respond- 162 light years away wave in the disk.” on the project while to provide care. They Mercy College’s ers. Students may have from Earth? Beta Canis Minoris participating in UT’s stabilize the patient EMT/Paramedic pro- the opportunity to gain The junior studying is what is known as a Research Experience and prepare them for gram allows students experience on Life physics at the Univer- Be star, a hot star that for Undergraduates transport to a medi- to begin their career Flight. -

The Electric Sun Hypothesis

Basics of astrophysics revisited. II. Mass- luminosity- rotation relation for F, A, B, O and WR class stars Edgars Alksnis [email protected] Small volume statistics show, that luminosity of bright stars is proportional to their angular momentums of rotation when certain relation between stellar mass and stellar rotation speed is reached. Cause should be outside of standard stellar model. Concept allows strengthen hypotheses of 1) fast rotation of Wolf-Rayet stars and 2) low mass central black hole of the Milky Way. Keywords: mass-luminosity relation, stellar rotation, Wolf-Rayet stars, stellar angular momentum, Sagittarius A* mass, Sagittarius A* luminosity. In previous work (Alksnis, 2017) we have shown, that in slow rotating stars stellar luminosity is proportional to spin angular momentum of the star. This allows us to see, that there in fact are no stars outside of “main sequence” within stellar classes G, K and M. METHOD We have analyzed possible connection between stellar luminosity and stellar angular momentum in samples of most known F, A, B, O and WR class stars (tables 1-5). Stellar equatorial rotation speed (vsini) was used as main parameter of stellar rotation when possible. Several diverse data for one star were averaged. Zero stellar rotation speed was considered as an error and corresponding star has been not included in sample. RESULTS 2 F class star Relative Relative Luminosity, Relative M*R *eq mass, M radius, L rotation, L R eq HATP-6 1.29 1.46 3.55 2.950 2.28 α UMi B 1.39 1.38 3.90 38.573 26.18 Alpha Fornacis 1.33 -

Clusters Nebulae & Galaxies

CLUSTERS, NEBULAE & GALAXIES A NOVICE OBSERVER’S HANDBOOK By: Prof. P. N. Shankar PREFACE In the normal course of events, an amateur who builds or acquires a telescope will use it initially to observe the Moon and the planets. After the thrill of seeing the craters of the Moon, the Galilean moons of Jupiter and its bands, and the rings of Saturn he(*) is usually at a loss as to what to do next; Mars and Venus are usually disappointing as are the stars (they don’t look any bigger!). If the telescope had good resolution one could observe binaries, but alas, this is often not the case. Moreover, at this stage, the amateur is unlikely to be willing to do serious work on variable stars or on planetary observations. What can he do with his telescope that will rekindle his interest and prepare him for serious work? I believe that there is little better for him to do than hunt for the Messier objects; this book is meant as a guide in this exciting adventure. While this book is primarily a guide to the Messier objects, a few other easy clusters and nebulae have also been included. I have tried, while writing this handbook, to keep in mind the difficulties faced by a beginner. Even if one has good star maps, such as those in Norton’s Star Atlas, a beginner often has difficulty in locating some of the Messier objects because he does not know what he is expected to see! A cluster like M29 is a little difficult because it is a sparse cluster in a rich field; M97 is nominally brighter than M76, another planetary, but is more difficult to see; M33 is an approximately 6th magnitude galaxy but is far more difficult than many 9th magnitude galaxies. -

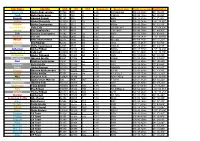

Vessels Insured Between 20Th February 2015 and 20Th February 2016

Steamship Mutual – Vessels insured between 20th February 2015 and 20th February 2016 Vessel Name IMO Certificate Number Vessel Name IMO Certificate Number Number Number 105 HYODONG CHEMI 8875968 55035 4 X OHNE NAMEN Unknown 823250 107 HYODONG CHEMI 9262285 55036 455 Unknown 823437 109 HYODONG CHEMI 9253997 61141 4US Unknown 61435 11 X 'C-' TYPE WORKBOATS Unknown 60430 4US Unknown 61550 13 B 23-52 Unknown 812791 54-33-YN Unknown 812896 14 X SKIFF BOATS Unknown 57241 550-1 9270309 55633 14-28-YL Unknown 812896 550-2 9270311 55613 15 PONTOONS Unknown 824019 550-3 9271107 55686 17' HOWARD 115 HP YAMAHA Unknown 55912 550-4 9271092 55684 18' HUGUES CRAFT 115 HP YAMAHA Unknown 55913 5604440 - DAGOBERT Unknown 812793 18' SEINE SKIFF / 75 HP Unknown 55888 600 Unknown 823960 1948 NTC-9 DOCK BARGE Unknown 61515 6498 - BEATRICE Unknown 812766 197 Unknown 823250 650-1 9369318 55670 198 Unknown 823250 650-10 9542647 55663 1999 25' SHAMROCK Unknown 61510 650-2 9369320 55678 1ST LT. JACK LUMMUS 8302454 61177 650-3 9369332 55676 20' RIVER ALUMINIUM BOAT / 75 HP Unknown 55887 650-4 9369344 55674 22' ALUMINIUM SKIFF / 115 HP Unknown 55891 650-5 9369356 55672 22' ALUMINIUM SKIFF / 185 HP Unknown 55889 650-6 9369368 55668 22' ALUMINIUM SKIFF / 200 HP Unknown 55890 650-7 9542611 55681 2229 Unknown 812793 650-8 9542623 55680 22-31-YT Unknown 812942 650-9 9542635 55669 23 Unknown 823250 69-25-YT Unknown 812896 2320 Unknown 812793 6L2XL1051235 Unknown 820539 2328 Unknown 812777 712 Unknown 823437 2363 FRANCIS-PIA Unknown 812793 750-1 9475076 55661 237-4990 Unknown 812825 750-2 9475337 55690 24' ALUMINUM WORKBOAT Unknown 58111 750-3 9475351 55688 2407 Unknown 813008 A 4 - 21302 Unknown 821017 2412 Unknown 813008 A 5 - 21303 Unknown 821017 2415 Unknown 812796 A AND A 1001570 60458 2420 Unknown 812799 A. -

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral Class Right Ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral class Right ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B8IVpMnHg 00h 08,388m 29° 05,433' Caph Beta Cassiopeiae 21133 432 2 2,27 F2III-IV 00h 09,178m 59° 08,983' Algenib Gamma Pegasi 91781 886 7 2,83 B2IV 00h 13,237m 15° 11,017' Ankaa Alpha Phoenicis 215093 2261 12 2,39 K0III 00h 26,283m - 42° 18,367' Schedar Alpha Cassiopeiae 21609 3712 21 2,23 K0IIIa 00h 40,508m 56° 32,233' Deneb Kaitos Beta Ceti 147420 4128 22 2,04 G9.5IIICH-1 00h 43,590m - 17° 59,200' Achird Eta Cassiopeiae 21732 4614 3,44 F9V+dM0 00h 49,100m 57° 48,950' Tsih Gamma Cassiopeiae 11482 5394 32 2,47 B0IVe 00h 56,708m 60° 43,000' Haratan Eta ceti 147632 6805 40 3,45 K1 01h 08,583m - 10° 10,933' Mirach Beta Andromedae 54471 6860 42 2,06 M0+IIIa 01h 09,732m 35° 37,233' Alpherg Eta Piscium 92484 9270 50 3,62 G8III 01h 13,483m 15° 20,750' Rukbah Delta Cassiopeiae 22268 8538 48 2,66 A5III-IV 01h 25,817m 60° 14,117' Achernar Alpha Eridani 232481 10144 54 0,46 B3Vpe 01h 37,715m - 57° 14,200' Baten Kaitos Zeta Ceti 148059 11353 62 3,74 K0IIIBa0.1 01h 51,460m - 10° 20,100' Mothallah Alpha Trianguli 74996 11443 64 3,41 F6IV 01h 53,082m 29° 34,733' Mesarthim Gamma Arietis 92681 11502 3,88 A1pSi 01h 53,530m 19° 17,617' Navi Epsilon Cassiopeiae 12031 11415 63 3,38 B3III 01h 54,395m 63° 40,200' Sheratan Beta Arietis 75012 11636 66 2,64 A5V 01h 54,640m 20° 48,483' Risha Alpha Piscium 110291 12447 3,79 A0pSiSr 02h 02,047m 02° 45,817' Almach Gamma Andromedae 37734 12533 73 2,26 K3-IIb 02h 03,900m 42° 19,783' Hamal Alpha -

Errata Planetarian - Vol

Errata Planetarian - Vol. 48, No. 1 March 2019 Page 18 corrected to reflect that the collaborative project involved six planetariums in Europe, not just in Germany Ad on page 55 replaced; original ad as appeared was dated for 2018 and was incorrect. Correct ad now appears With apologies, Sharon Shanks Editor 15 April 2019 Online PDF: ISSN 233333-9063 Vol. 48, No. 1 March 2019 Journal of the International Planetarium Society What motivates teachers to come? Page 20 STUNNING AND IMMERSIVE SHOWS IN 4K AND 8K! BIG & DIGITAL Celebrating 10 Years: 2009-2019 (702) 932-4045 www.biganddigital.com 180/360 - FULLDOME • 30FPS THIS IS REAL Ningaloo: Australia’s Other Great Reef Legends of the Northern Sky In Saturn’s Rings Touch the Stars Super Science Showcase TRANSFORMED GIANT SCREEN • 24FPS Touch the Stars In Saturn’s Rings Space Next IN SATURN’S RINGS NARRATED BY LEVAR BURTON NARRATED SOUND BY LEVAR BURTON BIG & DIGITAL :%SV2 STUDIOS PRODUCTION *STEPHEN VAN VUUREN cTHE GREENSBORO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WITH DMITRY SITKOVETSKY _PIETER SCHLOSSER SIDDHARTHA BARNHOORN DESIGN JEFF KING Dragons: Real Myths and Unreal Creatures „AREND ANTON BERNIE M. BOHIGAS CHRIS BONZA CLAUDIO BOTTACCINI CHARLES W. CLARK THOMAS GUSS TIA HIDAYAT STEPHEN KERN JAMIE LAWSON GUILLERMO MARTINEZ TIMOTHY MATSON ERIK RANKINS DAN SHAW CO- AIMILIA SMYRLI MICHAEL VAN VUUREN AMY VINEWARD JONATHAN AND JANE WARD PRODUCERS ANTONY BIELLO BILL EBERLY JASON HARWELL KEITH HAVILAND VAL KLAVANS LISA E. TATGE LEON TOOMEY DAVID AND LAURA VAN VUUREN SEGMENT xNATHALIEx A. CABROL EDMOND GRIN MICHAEL J. MALASKA pDON CLINE BAN LENG JAMES TOH PRODUCERS BILL EBERLY JASON HARWELL COLIN LEGG KEVIN MCABEE IAN REGAN Expedition Chesapeake jSTEPHEN VAN VUUREN MARIE STONE-VAN VUUREN kSTEPHEN VAN VUUREN INSATURNSRINGS.COM twose.ca/northernsky Max Laurence von Sydow Leboeuf DIRECTED & WRITTEN BY GREG MATKOSKY DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY JAMES NEIHOUSE ASC, SOUND DESIGN BY BRIAN EIMER SENIOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCER MICHAEL L. -

Brightest Stars : Discovering the Universe Through the Sky's Most Brilliant Stars / Fred Schaaf

ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. flast.qxd 3/5/08 6:28 AM Page vi ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page ii This book is dedicated to my wife, Mamie, who has been the Sirius of my life. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2008 by Fred Schaaf. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Illustration credits appear on page 272. Design and composition by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copy- right.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

Desert Skies – Winter 2016

Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association Observing our Desert Skies since 1954 Volume , Issue Inside this issue: NGC 2170 in Monoceros President’s 2 Letter Outreach 3-6 Members’ News 7 CAC Update 8-10 Feature Articles 11-13 Observing 14-18 Kid’s Page 17 Classifieds 12 Sponsors 12 TAAA member Larry Phillips took this image (above) of NGC 2170. This is both a reflection (blue) Contacts 19 and emission (red) nebulae and star birth area found in the constellation Monoceros (the Unicorn). The black streaks are absorption nebulae. This object is 2400 light years away and the image expands an area 15 light years across. © Larry Take Note! Phillips. Used by permission. Grand Canyon Star Party Larry describes this as a hybrid image combining H- Get Ready! alpha images with regular RGB images. He has 38 CAC Update and Big News! hours of exposure in this image. Astronomy Services Report This area of Orion and Monoceros, contains a large molecular cloud known as R2 Mon to which NGC Planetary Nebulae and 2170 belongs and Barnard’s Loop which Image: NGC 2170 as seen companions encompasses much of Orion. by VISTA (Visible Objects in Canis Minor At right, an infrared image of the same object Infrared Survey Kid’s Page (different orientation). The infrared image Telescope for penetrates the dark nebulosity revealing a stellar Determining Stellar Astronomy) reveals the nursery. Magnitude secrets of the Unicorn. Viewing Black Hole Event For more information about this object, visit http:// Credit: ESO Horizon www.robgendlerastropics.com/NGC2170text.html. Desert Skies Page 2 Volume LXI, Issue 4 Winter 2016 From Our President Our mission is to provide opportunities for members and the public to share the joy and excitement of astronomy through observing, education and fun.