Author's Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

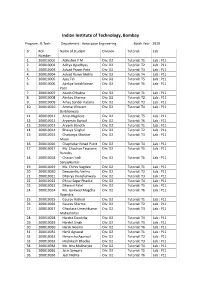

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. THE PRATYUTPANNA-BUDDHA-SAMMUKHAVASTHITA- SAMADHI-SUTRA AN ANNOTATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE TIBETAN VERSION WITH SEVERAL APPENDICES A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Australian National University August, 1979 by Paul Harrison This thesis is based on my own research carried out from 1976 to 1979 at the Australian National University. ABSTRACT The present work consists of a study of the Pratyutpanna-buddha- sammukhavasthita-samadhi-sutra (hereafter: PraS), a relatively early example of Mahayana Buddhist canonical literature. After a brief Intro duction (pp. xxi-xli), which attempts to place the PraS in its historical context, the major portion of the work (pp. 1-186) is devoted to an annotated English translation of the Tibetan version of the sutra, with detailed reference to the three main Chinese translations. Appendix A (pp. 187-252) then attempts a resolution of some of the many problems surrounding the various Chinese versions of the PraS. These are examined both from the point of view of internal evidence and on the basis of bibliographical information furnished by the Chinese Buddhist scripture-catalogues. Some tentative conclusions are advanced concerning the textual history of the PraS in China. -

In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury's

Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings Author: Arkamitra Ghatak Stable URL: http://www.globalhistories.com/index.php/GHSJ/article/view/105 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2017.105 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Apr. 2017), pp. 39–61 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2017 Arkamitra Ghatak License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings ARKAMITRA GHATAK Arkamitra Ghatak completed her major in History at Presidency University, Kolkata, in 2016, securing the first rank in the order of merit and was awarded the Gold Medal for Academic Ex- cellence. She is currently pursuing a Master in History at Presidency University. Her research interests include intellectual history in its plural spatialities, expressions of feminine subjec- tivities and spiritualities, as well as articulations of power and piety in cultural performances, especially folk festivals. She has presented several research papers at international student seminars organized at Presidency University, Jadavpur University and other organizations. -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

Prayers of Renunciation HINDUISM BUDDHISM KUNDALINI

Prayers of Renunciation: BUDDHISM - HINDUISM - KUNDALINI Ephesians)6:10.12)“10)Finally,)my)brethren,)be strong)in)the)Lord,)and)in)the) power)of)his)might.)11)Put)on)the)whole)armour)of)God,)that)ye)may)be)able)to stand)against)the)wiles)of)the)devil.)12)For)we)wrestle)not)against)Dlesh)and)blood,) but)against)principalities,)against)powers,)against)the)rulers)of)the)darkness) of)this)world,)against)spiritual)wickedness)in)high)places.” Amanda Buys’ Spiritual Covering This is a product of Kanaan Ministries, a non-profit ministry under the covering of: • Roly, Amanda’s husband for more than thirty-five years. • River of Life Family Church Pastor Edward Gibbens Vanderbijlpark South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 16 982 3022 Fax: +27 (0) 16 982 2566 Email: [email protected] There is no copyright on this material. However, no part may be reproduced and/or presented for personal gain. All rights to this material are reserved to further the Kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ ONLY. For further information or to place an order, please contact us at: P.O. Box 15253 27 John Vorster Avenue Panorama Plattekloof Ext. 1 7506 Panorama 7500 Cape Town Cape Town South Africa South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 21 930 7577 Fax: 086 681 9458 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.kanaanministries.org Office hours: Monday to Friday, 9 AM to 3 PM Kanaan International Website Website: www.eu.kanaanministries.org 2 contents Preface(... 5 Declara,on(of(confidence(in(GOD’s(Protec,on(... 8 Sealing9off(prayer(before(deliverance(... 9 Prayers'of'renuncia.on'for'Hinduism'.. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

What Do You Know About Hinduism?

UWS An Inclusive Community UWS Multifaith Chaplaincy September 2008 What do you know about Hinduism? Followers of the teachings of the Vedas are called Hindus. Hindu staff and students form a substantial part of the UWS community. Acknowledging and respecting Hindu identities at UWS therefore requires, in part, a basic understanding of what Hinduism and being a Hindu is about. About Hinduism Hinduism originated and developed in India over the last 3,000-3,500 years. It is the majority religion in India. Hindus believe in one Supreme God who manifests him/herself in many different forms. Some of these include Krishna, Durga, Ganesh, Sakti (Devi), Vishnu, Surya, Siva and Skanda (Murugan). Hindus believe: • in the Vedas (scriptures) • there is one Supreme God who is the creator of the universe • in reincarnation • that everyone creates their own destiny (karma) There are four major Hindu denominations classified according to their respective focus of worship. Vaishnavism Vaishnavism worship Vishnu and his incarnations, particularly Krishna and Rama, as the Supreme God. Saivism Saivites worship Siva (also spelt Shiva) as the Supreme God. Shaktism Shaktas worship God as the Shakti, Sri Devi or the Divine Mother in her many forms. Hindu Dress Code Traditional Hindu women wear the sari. Traditional male Hindus wear the Smartism white cotton dhoti. Smarta Hindus view the different manifestations of God as equivalent. They accept all major Hindu gods and are commonly known as liberal or Women in particular may wear a dot (tilak) of turmeric powder or other non-sectarian. coloured substance on their foreheads as a symbol of their religion. -

River Bank Primary Knowledge Organiser Year 6 Autumn 2 Being a Good Hindu

River Bank Primary Knowledge Organiser Year 6 Autumn 2 Being a good Hindu Key Vocabulary Important Facts Hinduism is a religion and dharma, or way of life, widely practised in the Indian subcontinent Brahman- God, Ultimate Reality and parts of Southeast Asia. Brahman and atman are vital concepts in the Hindu understanding of a human being. Atman- eternal self The Hindu story from the Mahabharata, the ‘man in the well’ presents one picture of Mahabharata- stories taken the way the world is for a Hindu. Hindus believe the atman (eternal self) is trapped in from the Bhagavad Gita the physical body and wants to escape the terrible dangers, but the human is distracted (Hindu’s holy scripture) by the trivial pleasures instead of trying to get out. This is a warning to Hindus that Punusharthas- four aims of life they should pay attention to finding the way to escape the cycle of life, death and rebirth. dharma – religious or moral Hindus believe in the idea of karma, and how actions bring good or bad karma. Hindus hold beliefs about samsara, where duty the atman travels through various reincarnations, to achieve moksha. artha – economic development The four aims of life (punusharthas) for Hindus are: Dharma – religious or moral duty moksha – liberation from the Artha – economic development, providing for family and society by honest cycle of birth and means rebirth/reincarnation Kama – beauty of life karma – the law of cause and Moksha – liberation from the cycle of birth and rebirth/reincarnation. effect By pursuing these aims contribute to good karma; doing things selfishly or in samsara – the cycle of life death ways that harm other living things brings bad karma. -

Cultural Dynamics

Cultural Dynamics http://cdy.sagepub.com/ Authoring (in)Authenticity, Regulating Religious Tolerance: The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism Jennifer Coleman Cultural Dynamics 2008 20: 245 DOI: 10.1177/0921374008096311 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Dynamics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cdy.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cdy.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cdy.sagepub.com/content/20/3/245.refs.html >> Version of Record - Oct 21, 2008 What is This? Downloaded from cdy.sagepub.com at The University of Melbourne Libraries on April 11, 2014 AUTHORING (IN)AUTHENTICITY, REGULATING RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE The Implications of Anti-Conversion Legislation for Indian Secularism JENNIFER COLEMAN University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This article explores the politicization of ‘conversion’ discourses in contemporary India, focusing on the rising popularity of anti-conversion legislation at the individual state level. While ‘Freedom of Religion’ bills contend to represent the power of the Hindu nationalist cause, these pieces of legislation refl ect both the political mobility of Hindutva as a symbolic discourse and the prac- tical limits of its enforcement value within Indian law. This resurgence, how- ever, highlights the enduring nature of questions regarding the quality of ‘conversion’ as a ‘right’ of individuals and communities, as well as reigniting the ongoing battle over the line between ‘conversion’ and ‘propagation’. Ul- timately, I argue that, while the politics of conversion continue to represent a decisive point of reference in debates over the quality and substance of reli- gious freedom as a discernible right of Indian democracy and citizenship, the widespread negative consequences of this legislation’s enforcement remain to be seen. -

Mill List - 2020

General Mills - Mill List - 2020 General Mills July 2020 - December 2020 Parent Mill Name Latitude Longitude RSPO Country State or Province District UML ID 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 17.00352 81.46973 No India Andhra Pradesh West Godavari PO1000008590 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000004269 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2 2.11272 100.27311 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000008154 Abago Extractora Braganza 4.286556 -72.134083 No Colombia Meta Puerto Gaitán PO1000008347 Ace Oil Mill Ace Oil Mill 2.91192 102.77981 No Malaysia Pahang Rompin PO1000003712 Aceites De Palma Aceites De Palma 18.0470389 -94.91766389 No Mexico Veracruz Hueyapan de Ocampo PO1000004765 Aceites Morichal Aceites Morichal 3.92985 -73.242775 No Colombia Meta San Carlos de Guaroa PO1000003988 Aceites Sustentables De Palma Aceites Sustentables De Palma 16.360506 -90.467794 No Mexico Chiapas Ocosingo PO1000008341 Achi Jaya Plantations Johor Labis 2.251472222 103.0513056 No Malaysia Johor Segamat PO1000003713 Adimulia Agrolestari Segati -0.108983 101.386783 No Indonesia Riau Kampar PO1000004351 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Sei Basau) -0.136967 101.3908 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000004358 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Singingi) -0.205611 101.318944 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000007629 ADIMULIA AGROLESTARI SEI TESO 0.11065 101.38678 NO INDONESIA Adimulia Palmo Lestari Adimulia Palmo Lestari -

Understanding Dharma and Artha in Statecraft Through Kautilya's

UNDERSTANDING DHARMA AND ARTHA IN STATECRAFT...| 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 53 July 2016 Understanding Dharma and Artha in Statecraft through Kautilya’s Arthashastra Pradeep Kumar Gautam 2 | P K GAUTAM Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-65-9 Disclaimer: It is certified that views expressed and suggestions made in this monograph have been made by the author in his personal capacity and do not have any official endorsement. First Published: July 2016 Price: Rs. 175 /- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Cover & Layout by: Geeta Kumari Printed at: M/S Manipal Technologies Ltd. UNDERSTANDING DHARMA AND ARTHA IN STATECRAFT...| 3 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ............................................................................ 7 2. The Concept of Dharma and Artha .................................... 14 3. Dharma in Dharmashastra and Arthashastra: A Comparative Analysis ...................................................... 37 4. Evaluating Dharma and Artha in the Mahabharata for Moral and Political Interpretations ........................... 72 5. Conclusion.............................................................................. 107 4 | P K GAUTAM UNDERSTANDING DHARMA AND ARTHA IN STATECRAFT...| 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank the panelists and participants in the two of my fellow seminars in 2015 for engaging with the topic with valuable insights, ideas and suggestions.