William Blake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Binary Domination and Bondage: Blake's Representations of Race

Binary Domination and Bondage: Blake’s Representations of Race, Nationalism, and Gender Katherine Calvin Submitted to the Department of English, Vanderbilt University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major, April 17, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………..………………………1 I. Blake’s Theory and Technique…………………….…………………………………..3 II. Revealing (and Contesting) the Racial Binary in Blake’s “The Little Black Boy”.......14 III. Colonization, Revolution, and the Consequences in America, A Prophecy …...……..33 IV. Gender and Rhetoric in Visions of the Daughters of Albion …………………..…..…63 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….90 Selected Bibliography……………………………………………………...………….93 Introduction “Thy soft American plains are mine and mine thy north and south/ Stampt with my signet are the swarthy children of the sun.”1 In William Blake’s Visions of the Daughters of Albion, the rapist Bromion decries his victim Oothoon on the basis of three conflated identities: race, colonial status, and gender. With his seed already sown in her womb, he pledges that her “swarthy” offspring will bear not only his genetic signet but also labor in subservience to him, the colonial master. Bromion himself encompasses everything Oothoon is not—he is a white male in the act of colonization while she is a female lashed to the identity of America, which is ethnically and politically subservient. Written in an age of burgeoning political and social radicalism, Visions nonetheless fails to conclude with the triumphant victory of Oothoon, -

Blake's Debt to Wollstonecraft in the Four Zoas

ARTICLE The Embattled Sexes: Blake’s Debt to Wollstonecraft in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Winter 1982/1983, pp. 172-183 PAGE 172 BLAKE AS ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY WINTER 1982-83 The Embattled Sexes: Blake's Debt to Wollstonecraft in The Four Zoas BY MICHAEL ACKLAND Our knowledge of Blake's acquaintance with the writings of with them to Wollstonecraft's conception of female poten- Mary Wollstonecraft is at once precise and frustratingly in- tial. Moreover, these ideas are further developed in The complete. We know he illustrated, and presumably also Four Zoas, where many crucial conceptual links between the read, her novel Original Stories from Real Life.' We also works of Blake and Wollstonecraft testify to the enduring have evidence in his earlier works, notably in Visions of the impact on him of her impassioned call for harmony, equali- Daughters of Albion, that he was influenced by the doc- ty and true friendship between the sexes. trines she expressed in Vindication of the Rights of Men Visions of the Daughters of Albion offers evidence not (1790) and Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).2 only of Blake's debt to Wollstonecraft but, more important- Moreover, both writers were frequent visitors at the booksel- ly, of his capacity to assimilate her ideas into his evolving cos- ler and publisher Joseph Johnson in the early 1790s; and mology. As commentators have noted, Oothoon's descrip- would, at the very least, have been known to each through tion of the negative and positive roles open to her sex seems word of mouth. -

The Memory of the American and French Revolutions in William Blake's

University of Bucharest Review Vol. III/2013, no. 1 (new series) Cultures of Memory, Memories of Culture Ruxanda Topor* THE MEMORY OF THE AMERICAN AND FRENCH REVOLUTIONS IN WILLIAM BLAKE’S AMERICA: A PROPHECY AND EUROPE: A PROPHECY Keywords: Blake; memory; revolution; America; Europe; France; England. Abstract: The French and American Revolutions were radical historical events of paramount significance for the subsequent fate of the two continents- Europe and America. They entailed deep social changes and fostered revolutionary ideas of freedom and equality that challenged the old hierarchies. William Blake, the English Romantic poet, lived amidst the turmoil and excitement brought by these mnemonically outstanding events- his lifespan comprised both revolutions. This paper sets out to explore his stance towards the French and American Revolutions in two of his prophetic books, Europe: A Prophecy and America: A Prophecy. The books reveal a harmonious blending of historical fact with mythological figures, such as Orc, the outstanding character that represents the revolutionary spirit. In addition, the presence of intertextuality in the poems, besides attesting to the pervasiveness and importance of these cultural upheavals at the time, authorizes subjective poetic memory and contributes to meaning-making, by reference to other works or documents dwelling on similar subjects. Blake recalls the images of noteworthy figures that played a major role in the revolutions; he also invokes sites of memory and scenes of war. Last but not least, the poet calls forth the emotional states dominating the people from both continents. Being an Englishman living in a monarchy, Blake stresses out throughout the books England’s attitude and reaction towards the French and American Revolutions, which shows his high concern for the fate of his country. -

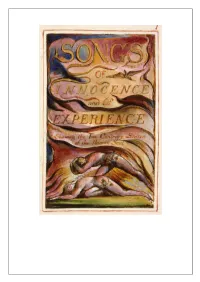

Songs of Innocence Is a Publication of the Pennsylvania State University

This publication of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence is a publication of the Pennsylvania State University. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any purpose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. William Blake’s Songs of Innocence, the Pennsylvania State University, Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, Hazleton, PA 18201-1291 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing student publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them, and as such is a part of the Pennsylvania State University’s Elec- tronic Classics Series. Cover design: Jim Manis; Cover art: William Blake Copyright © 1998 The Pennsylvania State University Songs of Innocence by William Blake Songs of Innocence was the first of Blake’s illuminated books published in 1789. The poems and artwork were reproduced by copperplate engraving and colored with washes by hand. In 1794 he expanded the book to in- clude Songs of Experience. Frontispiece 3 Songs of Innocence by William Blake Table of Contents 5 …Introduction 17 …A Dream 6 …The Shepherd The images contained 19 …The Little Girl Lost 7 …Infant Joy in this publication are 20 …The Little Girl Found 7 …On Another’s Sorrow copies of William 22 …The Little Boy Lost 8 …The School Boy Blakes originals for 22 …The Little Boy Found 10 …Holy Thursday his first publication. -

The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake's Poetry

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry Audrey F. Lytle Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons Recommended Citation Lytle, Audrey F., "The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1026. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1026 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~ THE AMBIGUITY OF "WEEPING" IN WILLIAM BLAKE'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Audrey F. Lytle August, 1968 LD S77/3 I <j-Ci( I-. I>::>~ SPECIAL COLL£crtoN 172428 Library Central W ashingtoft State Conege Ellensburg, Washington APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ H. L. Anshutz, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Robert Benton _________________________________ John N. Terrey TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 Method 1 Review of the Literature 4 II. "WEEPING" IMAGERY IN SELECTED WORKS 10 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 10 Songs of Innocence 11 --------The Book of Thel 21 Songs of Experience 22 Poems from the Pickering Manuscript 30 Jerusalem . 39 III. CONCLUSION 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY 57 APPENDIX 58 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I. -

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

Blake and Tradition: “The Little Girl Lost” and “The Little Girl Found”

DISCUSSION BCake and Tradition: “The LittCe GirC Lost” and “The LittCe GirC Found” Irene H. Chayes BCake/An ICCustrated QuarterCy, VoCume 4, Issue 1, August 19:0, pp. 25-28 -25- appears in an important though a little-known picture iden- tified by Essick as representing the "Genius of Shakes- peare" (repr. AnolLo N.S. LXXIX (1964), 321.) But the exact counterpart of the Sea Goddess is to be found st the center of the "Whirlwind of Lovers" (Divine Comedy nos. 10 and 1(E) where she is working to overcome those depri- vations whi ch would forever forbid the return of mankind into paradise. I shall maintain that this great picture acts as an explanatory sequel to ACP. ****£***$*** 2. Blake and Tradition: "The Little Girl Lost" and "The Little Girl Found" Irene H. Chayes Silver Spring, Maryland In his review of Kathleen Raine!s Blake and Tradition (BNL, Vol. Ill, Whole #11), Daniel Hughes mentions my name in connection with a pair of Blake's poems on which I have taken a stand in print. Since Mr. Hughes does not exa- mine any of the RaL ne read ngs he commends, I would like to supplement my incidental criticism of seven years ago. For at least some of us who have needed no introduc- tion to Thomas Taylor and have remained unconverted, what is at issue in the Neoplatonist chapters of Blake and Tra- dition is what was at issue w!en they were published first as separate essays: not the "poetic process," but critical method: not whether Blake knew Taylor's translations and commentaries (he probably did, as he knew other books of the time), but hew close they can or should be brought to his poetry; not what Taylor said but what Blake means. -

THE ART and ARGUMENT of "THE TYGER" Author(S): John E

THE ART AND ARGUMENT OF "THE TYGER" Author(s): John E. Grant Source: Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring 1960), pp. 38-60 Published by: University of Texas Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40753660 Accessed: 29-08-2016 20:11 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of Texas Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Texas Studies in Literature and Language This content downloaded from 132.236.27.217 on Mon, 29 Aug 2016 20:11:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE ART AND ARGUMENT OF "THE TYGER" By John E. Grant I. The Poem Blake's "The Tyger" is both the most famous of his poems and one of the most enigmatic. It is remarkable, considering its popularity, that there is no single study of the poem which is not marred by inaccuracy or inattention to crucial details. Partly as a result, the two most recent popular interpretations of "The Tyger" are very uneven in quality.1 Another reason that the meaning of the poem has been only partially revealed is that the textual basis for interpretation is insecure. -

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake Author(s): PAUL MINER Source: Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Winter 1962), pp. 59-73 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23091046 Accessed: 20-06-2016 19:39 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 19:39:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAUL MINER* r" The TygerGenesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake There is the Cave, the Rock, the Tree, the Lake of Udan Adan, The Forest and the Marsh and the Pits of bitumen deadly, The Rocks of solid fire, the Ice valleys, the Plains Of burning sand, the rivers, cataract & Lakes of Fire, The Islands of the fiery Lakes, the Trees of Malice, Revenge And black Anxiety, and the Cities of the Salamandrine men, (But whatever is visible to the Generated Man Is a Creation of mercy & love from the Satanic Void). (Jerusalem) One of the great poetic structures of the eighteenth century is William Blake's "The Tyger," a profound experiment in form and idea. -

Lyca” – Blake’S Artistic Foster-Child

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.8.Issue 2. 2020 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (April-June) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE “LYCA” – BLAKE’S ARTISTIC FOSTER-CHILD PAUL POTTAKKARAN Guest Lecturer, St. Aloysius College, Elthuruth, Kerala Abstract William Blake is believed to be a master in portraying life and nature in words as well as images. His poems and paintings explore the relationship between human life and nature. The Lamb and The Tyger are not just poems but reflections of human life within the animal world. “Lyca” is the girl lost and found, in his twin poems, The Little Girl Lost and The Little Girl Found. The nature accepts, lulls and fosters her innocence. The poems open multiple levels of interpretation along with the fancied journey of Article Received:27/03/2020 little Lyca. She follows the songs of the birds, the music of the nature and is lost in a Article Accepted: 30/04/2020 desert like a teenage girl answering the forbidden calls of the nature. These symbols Published online: 06/05/2020 of nature and sexuality run parallel throughout the poem. This work studies Lyca, the DOI: 10.33329/rjelal.8.2.86 little girl, as the poet’s device to represent sexuality as an innocent journey towards nature and identity. Keywords: Poetry, nature, sexuality. William Blake showed immense love towards Tired and woe-begone, nature in his personal and artistic lives. The poet, Hoarse with making moan: who is believed to play a major role in the transition Arm in arm, seven days, of English Poetry from Neo-classicism to Romanticism, led a liberal life. -

Songs of Innocence and of Experience by William Blake

SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE BY WILLIAM BLAKE 1789-1794 Songs Of Innocence And Of Experience By William Blake. This edition was created and published by Global Grey 2014. ©GlobalGrey 2014 Get more free eBooks at: www.globalgrey.co.uk No account needed, no registration, no payment 1 SONGS OF INNOCENCE INTRODUCTION Piping down the valleys wild Piping songs of pleasant glee On a cloud I saw a child. And he laughing said to me. Pipe a song about a Lamb: So I piped with merry chear, Piper pipe that song again— So I piped, he wept to hear. Drop thy pipe thy happy pipe Sing thy songs of happy chear, 2 So I sung the same again While he wept with joy to hear. Piper sit thee down and write In a book that all may read— So he vanish’d from my sight, And I pluck’d a hollow reed. And I made a rural pen, And I stain’d the water clear, And I wrote my happy songs, Every child may joy to hear 3 THE SHEPHERD How sweet is the Shepherds sweet lot, From the morn to the evening he strays: He shall follow his sheep all the day And his tongue shall be filled with praise. For he hears the lambs innocent call. And he hears the ewes tender reply. He is watchful while they are in peace, For they know when their Shepherd is nigh. 4 THE ECCHOING GREEN The Sun does arise, And make happy the skies. The merry bells ring, To welcome the Spring.