The Memory of the American and French Revolutions in William Blake's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in the Four Zoas

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1983 Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.173-189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ackland: Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas by MICHAEL ACKLAND RIZEN is at once one of Blake's most easily recognizable characters U and one of his most elusive. Pictured often as a grey, stern, hover ing eminence, his wide-outspread arms suggest oppression, stultifica tion, and limitation. He is the cruel, jealous patriarch of this world, the Nobodaddy-boogey man-god evoked to quieten the child, to still the rabble, to repress the questing intellect. At other times in Blake's evolv ing mythology he is an inferior demiurge, responsible for this botched and fallen creation. In political terms, he can project the repressive, warmongering spirit of Pitt's England, or the collective forces of social tyranny. More fundamentally, he is a personal attribute: nobody's daddy because everyone creates him. As one possible derivation of his name suggests, he is "your horizon," or those impulses in each of us which, through their falsely assumed authority, limit all man's other capabilities. Yet Urizen can, at times, earn our grudging admiration. -

William Blake

THECAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO WILLIAM BLAKE EDITED BY MORRIS EAVES Department of English University of Rochester published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge companion to William Blake / edited by Morris Eaves. (Cambridge companions to literature) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Blake, William, 1757–1827 – Criticism and interpretation – Handbooks, manuals, etc. i. Eaves, Morris ii. Series. pr4147. c36 2002 821.7 –dc21 2002067068 isbn 0 521 78147 7 hardback isbn 0 521 78677 0 paperback CONTENTS List of illustrations page vii Notes on contributors xi Acknowledgments xiv List of abbreviations xv Chronology xvii aileen ward 1 Introduction: to paradise the hard way 1 morris eaves Part I Perspectives 2 William Blake and his circle 19 aileen ward 3 Illuminated printing 37 joseph viscomi 4 Blake’s language in poetic form 63 susan j. -

Binary Domination and Bondage: Blake's Representations of Race

Binary Domination and Bondage: Blake’s Representations of Race, Nationalism, and Gender Katherine Calvin Submitted to the Department of English, Vanderbilt University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major, April 17, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………..………………………1 I. Blake’s Theory and Technique…………………….…………………………………..3 II. Revealing (and Contesting) the Racial Binary in Blake’s “The Little Black Boy”.......14 III. Colonization, Revolution, and the Consequences in America, A Prophecy …...……..33 IV. Gender and Rhetoric in Visions of the Daughters of Albion …………………..…..…63 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….90 Selected Bibliography……………………………………………………...………….93 Introduction “Thy soft American plains are mine and mine thy north and south/ Stampt with my signet are the swarthy children of the sun.”1 In William Blake’s Visions of the Daughters of Albion, the rapist Bromion decries his victim Oothoon on the basis of three conflated identities: race, colonial status, and gender. With his seed already sown in her womb, he pledges that her “swarthy” offspring will bear not only his genetic signet but also labor in subservience to him, the colonial master. Bromion himself encompasses everything Oothoon is not—he is a white male in the act of colonization while she is a female lashed to the identity of America, which is ethnically and politically subservient. Written in an age of burgeoning political and social radicalism, Visions nonetheless fails to conclude with the triumphant victory of Oothoon, -

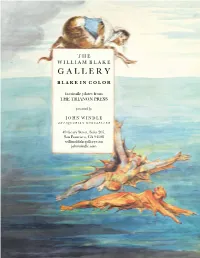

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

ENG 439: William Blake Spring 2011 W 6:00-9:15 Richard Squibbs

ENG 439: William Blake Spring 2011 W 6:00-9:15 Richard Squibbs McGaw 232 (773-325-7657) Office hours: Mon 1:30-2:30; Wed 5:00-6:00 & by appt. Email: [email protected] Required texts: The Early Illuminated Books (ISBN: 9780691001470) Songs of Innocence (ISBN: 9780486227641) Songs of Experience (ISBN: 9780486246369) America: A Prophecy & Europe: A Prophecy (ISBN: 9780486245485) The Book of Urizen (ISBN: 9780486298016) Course requirements: One 5-8 page essay (w/two secondary sources); one 3-page research essay proposal & 8-item annotated bibliography; final 10-20 page research essay. The essays together count for 4/5 of your final grade; the bibliography counts for 1/5 of your final grade. This is a seminar-style course, which means that regular and active participation in discussion is crucial. You are allowed one absence without penalty; after that, each absence will proportionately lower your final grade for the course. Schedule of Readings Wed 3/30 Introduction Revelation ; There Is No Natural Religion I & II; All Religions Are One Wed 4/6 Songs of Innocence Wed 4/13 Book of Thel Lecture: Prophecy ( Isaiah , Ezekiel , Daniel) Wed 4/20 Marriage of Heaven and Hell Lecture: Theosophy ( Swedenborg , Boehme ) Wed 4/27 Visions of the Daughters of Albion [Essay #1 due] Wed 5/4 America: A Prophecy Lecture: The American and French Revolutions & republican art Wed 5/11 America: A Prophecy ; Europe: A Prophecy **[3-page proposal due w/annotated bibliography due via email by Fri 5/13]** Wed 5/18 Songs of Experience Wed 5/25 The Book of Urizen & Genesis Wed 6/1 open day Final essay due Wednesday 6/8 in my mailbox in McGaw 232 by 6:00pm Preliminary Bibliography (titles in boldface are available in the Richardson library) Ackroyd, Peter. -

William Blake (1757-1827)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN William Blake (1757-1827) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Blake's Poetry and Designs

A NORTON CRITICAL EDITION BLAKE'S POETRY AND DESIGNS ILLUMINATED WORKS OTHER WRITINGS CRITICISM Second. Edition Selected and Edited by MARY LYNN JOHNSON UNIVERSITY OF IOWA JOHN E. GRANT UNIVERSITY OF IOWA W • W • NORTON & COMPANY • New York • London Contents Preface to the Second Edition xi Introduction xiii Abbreviations xvii Note on Illustrations xix Color xix Black and White XX Key Terms XXV Illuminated Works 1 ALL RELIGIONS ARE ONE/THERE IS NO NATURAL RELIGION (1788) 3 All Religions Are One 5 There Is No Natural Religion 6 SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE (1789—94) 8 Songs of Innocence (1789) 11 Introduction 11 The Shepherd 13 The Ecchoing Green 13 The Lamb 15 The Little Black Boy 16 The Blossom 17 The Chimney Sweeper 18 The Little Boy Lost 18 The Little Boy Found 19 Laughing Song 19 A Cradle Song 20 The Divine Image 21 Holy Thursday 22 Night 23 Spring 24 Nurse's Song 25 Infant Joy 25 A Dream 26 On Anothers Sorrow 26 Songs of Experience (1793) 28 Introduction 28 Earth's Answer 30 The Clod & the Pebble 31 Holy Thursday 31 The Little Girl Lost 32 The Little Girl Found 33 vi CONTENTS The Chimney Sweeper 35 Nurses Song 36 The Sick Rose 36 The Fly 37 The Angel 38 The Tyger 38 My Pretty Rose Tree 39 Ah! Sun-Flower 39 The Lilly 40 The Garden of Love 40 The Little Vagabond 40 London 41 The Human Abstract 42 Infant Sorrow 43 A Poison Tree 43 A Little Boy Lost 44 A Little Girl Lost 44 To Tirzah 45 The School Boy 46 The Voice of the Ancient Bard 47 THE BOOK OF THEL (1789) 48 VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION (1793) 55 THE MARRIAGE OF HEAVEN AND HELL (1790) 66 AMERICA A PROPHECY (1793) 83 EUROPE A PROPHECY(1794) 96 THE SONG OF Los (1795) 107 Africa 108 Asia 110 THE BOOK OF URIZEN (1794) 112 THE BOOK OF AHANIA (1794) 130 THE BOOK OF LOS (1795) 138 MILTON: A POEM (1804; c. -

Complete Poetry and Prose-William Blake

www.GetPedia.com *More than 150,000 articles in the search database *Learn how almost everything works The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake All Religions are One For the Sexes: The Annotations to: There is No Natural Gates of Paradise Lavater's Aphorisms Religion [a] On Homers Poetry on Man There is No Natural On Virgil Swedenborg's Heaven Religion [b] The Ghost of Abel and Hell The Book of Thel [Laocoön] Swedenborg's Divine Songs of Innocence and Tiriel Love and Divine Wisdom of Experience (Index) The French Revolution Swedenborg's Divine For Children: The Gates The Four Zoas Providence of Paradise Vala Night the First An Apology for the The Marriage of Vala Night the Bible by R. Watson Heaven and Hell [Second] Bacon's Essays Moral, Visions of the Vala Night the Economical and Political Daughters of Albion Third Boyd's Historical America a Prophecy Vala Night the Notes on Dante Europe a Prophecy Fourth The Works of Sir The Song of Los Vala Night the Fifth Joshua Reynolds The [First] Book of Vala Night the Sixth Spurzheim's Urizen Vala Night the Observations on Insanity The Book of Ahania Seventh Berkeley's Siris The Book of Los Vala Night the Wordsworth's Poems Milton: a Poem in 2 Eighth Wordsworth's Preface Books Vala Night the to The Excursion Jerusalem: The Ninth Being The Last Thorton's The Lord's Emanation of The Giant Judgment Prayer, Newly Translated Albion Poetical Sketches Cellini(?) frontispiece [An Island in the Moon] Young's Night To the Public [Songs and Ballads] Thoughts Chap: 1 [plates4-27] (Index) [Inscriptions and Notes On To the Jews [The Pickering or For Pictures] "The fields from Manuscript] (Index) [Miscellaneous Prose] Islington to Marybone [Satiric Verses and [The Letters] (Index) Chap: 2 [plates Epigrams] 28-50] The Everlasting Gospel To the Deists [Blake's Exhibition and "I saw a Monk of Catalogue of 1809] Charlemaine" [Descriptions of the Chap 3 [plates Last Judgment] 53-75] [Blake's Chaucer: To the Christians Prospectuses] "I stood among my [Public Address] valleys of the south" "England! awake! . -

Blake's Minor Prophecies: a Study of the Development of His Major

70-2 6 ,34-1 NELSON, John Walter, 1931- BLAKE’S MINOR PROPHECIES: A STUDY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF HIS MAJOR PROPHETIC MODE. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan (c) John Walter Nelson 1971 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS, RECEIVED BLAKE'S MINOR PROPHECIES? A STUDY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF HIS MAJOR PROPHETIC MODE A DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Walter Nelson, B.A., B«D., M«A. ^1**vU J U tO The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by Adviser Department of English ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance in the completion of this study I especially thank my adviser, Dr. Albert Kuhn, who con tinued to read my rough drafts even while he was in England for a year of private study and who eventually underwent surgery that year for eyestrain. I also thank Professors Edward Corbett and Edwin Robbins, who served as second readers, Professor Franklin Luddens, who assisted in my oral examination, and my wife, whose hard work and patience made my years at Ohio State financially and emotionally possible. VITA September 23 1931* • Born— Hartford, Connecticut 1953- . - . • • • • B.A., Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut 1956® • • c 9 o • B.D., Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1965. » • • • • M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1966—1970> • • • • Teaching Associate, Department of English, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: English Literature of the Eighteenth Century. -

Europe: a Prophecy

EUROPE: A PROPHECY William Blake EUROPE: A PROPHECY Table of Contents EUROPE: A PROPHECY.......................................................................................................................................1 William Blake................................................................................................................................................1 Preludium.......................................................................................................................................................1 A Prophecy.....................................................................................................................................................2 i EUROPE: A PROPHECY William Blake This page copyright © 2001 Blackmask Online. http://www.blackmask.com • Preludium • A Prophecy `Five windows light the cavern'd Man: thro' one he breathes the air; Thro' one hears music of the spheres; thro' one the Eternal Vine Flourishes, that he may receive the grapes; thro' one can look And see small portions of the Eternal World that ever groweth; Thro' one himself pass out what time he please, but he will not; For stolen joys are sweet, and bread eaten in secret pleasant.' So sang a Fairy, mocking, as he sat on a streak'd tulip, Thinking none saw him: when he ceas'd I started from the trees, And caught him in my hat, as boys knock down a butterfly. `How know you this,' said I, `small Sir? where did you learn this song?' Seeing himself in my possession, thus he answer'd me: `My Master, I am yours! command -

The Image of Canada in Blake's America a Prophecy

MINUTE PARTICULAR The Image of Canada in Blake’s America a Prophecy Warren Stevenson Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 27, Issue 3, Winter 1993-1994, pp. 72-74 11 BLAKE/ANILLUSTRA TED QUARTERL Y Winter 1993/94 Nor wandering thought. We thank thee, 1 6 vols. (London: John Murray, 1830) 2: gracious God! 140-79. The Image of Canada For all its treasured memories! tender 2 Henry Crabb Robinson records reading in Blake's America a cares, Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Ex- Fond words, bright, bright sustaining perience to Wordsworth on 24 May 1812 Prophecy looks unchanged and notes, "He was pleased with some of Through tears and joy. O Father! most of them, and considered Blake as having the all elements of poetry a thousand times more Warren Stevenson We thank, we bless Thee, for the than either Byron or Scott." priceless trust, 3 Some early reviews did take notice of Through Thy redeeming Son the unreliability of certain aspects of he theme oi America a Prophecy' vouchsafed, to those Cunningham's account. See, for instance, is less the emergence of a new That love in Thee, of union, in Thy sight, The Athenaeum for Saturday, 6 February T And in Thy heavens, immortal!—Hear 1830 and the London University Magazine nation—about whose post-revolu- our prayer! for March 1830. John Linnell also made no tionary course, involving as it did the Take home our fond affections, purified secret of his dismay at the liberties Cunning- persistence of slavery, Blake had To spirit-radiance from all earthly stain; ham took with the truth. -

The Rise and Fa1l of the H/1Yth of Orc(2)

鳥取大学教育学部研究報告 人文・社会科学 第49巻 第1号 (1998) The Rise and Fa1l of the h/1yth of Orc(2): mythogenesis in Blakeも A%ヮ 狗切 and in予 々sんηsげ 肋σ Dα夕ぽカル郷 げ 4みケο% Ayako Wada The title page of∠ 4夕″夕ιttθα Shows that the work覇 〆as produced in 1793. Hoヽ vever, there is a strong possibility that the work took its present form later than that date.Geoffrey I(eynes and D.ヽr. Erdman speculated thatッ 4物 θα was completed in 1794 or 1795, but this idea was not researched further and Ⅵ/as denied by G.E. Bentley. I(eynes noticed that no copies of 4夕 %ι 夕ηεα had▼〆atermarks dated earher than 1794,l but Bentley dis■ lissed the indication that aH copies were made later than 1794 by pointing out that copies C― L, without dated、 vatermarks,could be earlier.2 Erdman, on the other hand, perceived a difference in spirit and the quanty of dra、ving between the cancened plates and the plates integrated into the、 vork.3 He alSo argued thatッ4賜 θα was completed around 1795, pointing out the closeness between the design of the second page of the Preludium of 4物 ιηtt and the text of T力ι Sθ ηgげ Lθs.4 Bentley found little validity in Erdman's suggestion and concluded thus:`there seems to be no sound reason not to accept the date of``1793" on the title page'.5 frhe existence of a gap between the date on the title page and the actual date of completion of a市 〆ork is not unusual、 vith Blake. Bentley beheved the date on the title page because of the Prospectus of October 10, 1793, in、 vhich ッ4%珍ι%εα ヽVaS advertised: :AInerica, a Prophecy, in lnunlinated Printing.