Oppositional Christian Symbolism and Salvation in Blake's America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Another Source for Blake's Orc

MINUTE PARTICULAR Another Source for Blake’s trc Randel Helms Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 15, Issue 4, Spring 1982, pp. 198-199 198 By omitting all reference to Blake's life and writings, Ballard has written a tour de force that in some ways gets closer to the heart of Blake's MINUTE vision than the more explicitly Blakean novels. [My thanks to Roberto Cuooi and Barbara Heppner for PARTICULARS drawing my attention to the last too novels.] BLAKE AND THE NOVELISTS ANOTHER SOURCE FOR BLAKE'S ORC Christopher Heppner Randel Helms recurring fascination in the reading of illiam Blake derived the name and character- Blake is to wonder how some of his statements istics of his figure Ore from a variety of A and exhortations would feel if lived out in Wsources, combining them to produce the a real life—one's own, for example. Many of the various aspects of the character in such poems as novelists who have used Blake have explored this America, The Four Zoas and The Song of Los. The question, from a variety of perspectives. Joyce hellish aspects of Ore probably come from the Latin Cary in The Horse's Mouth gave us one version of the Orcus, the abode of the dead in Roman mythology and artist as hero, living out his own interpretation of an alternate name for Dis, the god of the underworld. Blake. Colin Wilson's The Glass Cage made its hero In Tiriel, Ijim describes Uriel's house, after his a Blake critic, but an oddly reclusive one, who sons have expelled him, as "dark as vacant Orcus."1 appears a little ambivalent in his lived responses The libidinous aspect of Ore may well come, as David to the poet, and is now writing about Whitehead. -

Postgraduate English: Issue 15

Farrell Postgraduate English: Issue 15 Postgraduate English www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english ISSN 1756-9761 Issue 15 March 2007 Editors: Ollie Taylor and Kostas Boyiopoulos Revolution & Revelation: William Blake and the Moral Law Michael Farrell* * University of Oxford ISSN 1756-9761 1 Farrell Postgraduate English: Issue 15 Revolution & Revelation: William Blake and the Moral Law Michael Farrell University of Oxford Postgraduate English, Issue 15, March 2007 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, despite its parodic form and function, is Blake’s personal and politico-theological manifesto outlining his fervent opposition to institutionalised religion and the oppressive moral laws it prescribes. It ultimately concerns the opposition between the Spirit of Prophecy and religious Law. For Blake, true Christianity resides in the cultivation of human energies and in the fulfilment of human potential and desire – the cultivation for which the prophets of the past are archetypal representatives – yet the energies of which the Mosaic Decalogue inhibits. Blake believes that all religion has its provenance in the Poetic Genius which “is necessary from the confined nature of bodily sensation” (Erdman 1) to the fulfilment of human potential. Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell” demonstrate how the energies underlying the true religious and potentially revolutionary consciousness are to be cultivated. He is especially concerned with repressed sexual energies of bodily sensation, stating in The Marriage that “the whole creation will be consumed and appear infinite and holy … This will come to pass by an improvement of sexual enjoyment” (39). He subsequently exposes the relativity of moral codes and hence “the vanity of angels” who “speak of themselves as the only wise” (42) – that is, the fallacy of institutionalised Christianity and its repressive moral law or “sacred codes” which are established upon “systematic reasoning”. -

Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in the Four Zoas

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1983 Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.173-189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ackland: Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas by MICHAEL ACKLAND RIZEN is at once one of Blake's most easily recognizable characters U and one of his most elusive. Pictured often as a grey, stern, hover ing eminence, his wide-outspread arms suggest oppression, stultifica tion, and limitation. He is the cruel, jealous patriarch of this world, the Nobodaddy-boogey man-god evoked to quieten the child, to still the rabble, to repress the questing intellect. At other times in Blake's evolv ing mythology he is an inferior demiurge, responsible for this botched and fallen creation. In political terms, he can project the repressive, warmongering spirit of Pitt's England, or the collective forces of social tyranny. More fundamentally, he is a personal attribute: nobody's daddy because everyone creates him. As one possible derivation of his name suggests, he is "your horizon," or those impulses in each of us which, through their falsely assumed authority, limit all man's other capabilities. Yet Urizen can, at times, earn our grudging admiration. -

William Blake

THECAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO WILLIAM BLAKE EDITED BY MORRIS EAVES Department of English University of Rochester published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge companion to William Blake / edited by Morris Eaves. (Cambridge companions to literature) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Blake, William, 1757–1827 – Criticism and interpretation – Handbooks, manuals, etc. i. Eaves, Morris ii. Series. pr4147. c36 2002 821.7 –dc21 2002067068 isbn 0 521 78147 7 hardback isbn 0 521 78677 0 paperback CONTENTS List of illustrations page vii Notes on contributors xi Acknowledgments xiv List of abbreviations xv Chronology xvii aileen ward 1 Introduction: to paradise the hard way 1 morris eaves Part I Perspectives 2 William Blake and his circle 19 aileen ward 3 Illuminated printing 37 joseph viscomi 4 Blake’s language in poetic form 63 susan j. -

The Cea Forum 2021

Winter/Spring THE CEA FORUM 2021 William Blake’s Emoji: Composite Art and Composition Matthew Leporati College of Mount Saint Vincent “If you look closely at the letter C,” I explained to the class as I zoomed in on the title of William Blake’s poem “The Chimney Sweeper” on the projector screen, “you can see that inside the letter, there’s a child hunched over with his cleaning tools.” I paused for a moment and gestured toward the figure as I circled it with the laptop’s cursor. “Blake forces us to question the distinction between text and image. It’s a letter, but it’s also a picture.” “So it’s like an emoji,” one student laughed from the other side of the room. Several others nodded in agreement. I was teaching William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience in my freshman writing class, Writing in Context I at the College of Mount Saint Vincent, and we were examining “The Chimney Sweeper” from Songs of Innocence (Figure 1).1 This poem famously highlights the injustice of child labor in the eighteenth century and indirectly condemns the Church of England for tacitly supporting the exploitation of children by offering to the poor a message of conformity to the social order. Like most of Blake’s poems, the Songs were the product of his unique methods of printing: an engraver by trade, Blake wrote, illustrated, engraved, printed, colored, and sold his works with the help only of his wife, Catherine.2 The results of this process are what W.J.T. -

The Bravery of William Blake

ARTICLE The Bravery of William Blake David V. Erdman Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 10, Issue 1, Summer 1976, pp. 27-31 27 DAVID V. ERDMAN The Bravery of William Blake William Blake was born in the middle of London By the time Blake was eighteen he had been eighteen years before the American Revolution. an engraver's apprentice for three years and had Precociously imaginative and an omnivorous reader, been assigned by his master, James Basire, to he was sent to no school but a school of drawing, assist in illustrating an antiquarian book of at ten. At fourteen he was apprenticed as an Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain. Basire engraver. He had already begun writing the sent Blake into churches and churchyards but exquisite lyrics of Poetioal Sketches (privately especially among the tombs in Westminster Abbey printed in 1783), and it is evident that he had to draw careful copies of the brazen effigies of filled his mind and his mind's eye with the poetry kings and queens, warriors and bishops. From the and art of the Renaissance. Collecting prints of drawings line engravings were made under the the famous painters of the Continent, he was happy supervision of and doubtless with finishing later to say that "from Earliest Childhood" he had touches by Basire, who signed them. Blake's dwelt among the great spiritual artists: "I Saw & longing to make his own original inventions Knew immediately the difference between Rafael and (designs) and to have entire charge of their Rubens." etching and engraving was yery strong when it emerged in his adult years. -

Images of the Divine Vision in the Four Zoas

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 1973 Nature, Reason, and Eternity: Images of the Divine Vision in The Four Zoas Cathy Shaw Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Shaw, Cathy, "Nature, Reason, and Eternity: Images of the Divine Vision in The Four Zoas" (1973). Honors Papers. 754. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/754 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURE, nEASON, and ETERNITY: Images of the Divine Vision in The }1'our Zoas by Cathy Shaw English Honors }i;ssay April 26,1973 In The Four Zoas Blake wages mental ,/Ur against nature land mystery, reason and tyranny. As a dream in nine nights, the 1..Jorld of The Four Zoas illustrates an unreal world which nevertheless represents the real t-lorld to Albion, the dreamer. The dreamer is Blake's archetypal and eternal man; he has fallen asleep a~ong the floitlerS of Beulah. The t-lorld he dreams of is a product of his own physical laziness and mental lassitude. In this world, his faculties vie 'tvi th each other for pOi-vel' until the ascendence of Los, the imaginative shapeI'. Los heralds the apocalypse, Albion rem-Jakas, and the itwrld takes on once again its original eternal and infinite form. -

Binary Domination and Bondage: Blake's Representations of Race

Binary Domination and Bondage: Blake’s Representations of Race, Nationalism, and Gender Katherine Calvin Submitted to the Department of English, Vanderbilt University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major, April 17, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………..………………………1 I. Blake’s Theory and Technique…………………….…………………………………..3 II. Revealing (and Contesting) the Racial Binary in Blake’s “The Little Black Boy”.......14 III. Colonization, Revolution, and the Consequences in America, A Prophecy …...……..33 IV. Gender and Rhetoric in Visions of the Daughters of Albion …………………..…..…63 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….90 Selected Bibliography……………………………………………………...………….93 Introduction “Thy soft American plains are mine and mine thy north and south/ Stampt with my signet are the swarthy children of the sun.”1 In William Blake’s Visions of the Daughters of Albion, the rapist Bromion decries his victim Oothoon on the basis of three conflated identities: race, colonial status, and gender. With his seed already sown in her womb, he pledges that her “swarthy” offspring will bear not only his genetic signet but also labor in subservience to him, the colonial master. Bromion himself encompasses everything Oothoon is not—he is a white male in the act of colonization while she is a female lashed to the identity of America, which is ethnically and politically subservient. Written in an age of burgeoning political and social radicalism, Visions nonetheless fails to conclude with the triumphant victory of Oothoon, -

How the Devils in William Blake's Marriage Of

A Thesis entitled Burning Sensations: How the Devils in William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell Illustrate the Creation of New Texts by: Joshua A. Mooney as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts Degree with Honors in English Thesis Director:___________________________ Dr. Andrew Mattison Honors Advisor:___________________________ Dr. Melissa Valiska Gregory Honors Program Director:___________________________ Dr. Thomas E. Barden University of Toledo DECEMBER 2010 Abstract Critics approaching Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790?) have often described the Devils appearing in the work to be creatures that exemplify creative energy. This creative energy is seen by David V. Erdman as part of Blake’s revolutionary sympathies and by Northrop Frye as part of a mythical representation of actively procreative forces. I wish to explore how the Devils seen in MHH function as exemplary of a relation between existing texts such as those of the Bible or “Swedenborg’s volumes” ( MHH 19) 1 and the minds of those who are inspired to create new works from them. The Devils featured throughout MHH do not exist merely to destroy or negate existing texts in order to make way for new ones, nor do they wish to subjugate the minds of those who adhere to such documents to a status beneath that of themselves. Rather, the Devils enact their fiery energies upon religious texts or minds, altering them in an act of renewal that does not destroy but empowers the mind or text, treating it as if it were a medium for creating new art. I explore various examples of this devilish energy as illustrating of a creative vision that involves a dynamic relationship between a text and the human mind’s experience of it. -

Between 1789 and 1792

鳥取大学教育学部研究報告 人文 社会科学 第 48巻 第 2号 (1997) The Rise and Fa1l of the Myth of Orc(1): Orc's Origin Traced in Blake's Poems Composed Between 1789 and 1792 Ayako Wada Northrop Frye attributed the failure of予石α,α/T力 ι Яθttγ Zο αs partly to the indeterminacy of who― Orc or Los― was the true protagonist in precipitating the Last Judgment.He says: The Last 」udgment silnply starts off 、vith a bang, as an instinctive shudder of self― preservation against a tyranny of intolerable menace.If so,then it is not really the work of Los....it iS old revolutionary doctrine of a spontaneous reappearance of Orc.ユ Frye overlooked the hidden dyna■ �cs by which Los attains heroic status and thereby occasions the LastJudgment.Remarkable,nevertheless,is his insight that Orc used to be the central figure of レ物,α.Indeed, レ物′α was almost certainly proieCted to evolve from the fragmentary myths developed in Blake's earlier works a comprehensive vision of the Fall and Judgment Of the cosmic h/1an.Those fragmentary myths came together when Orc、vas identified as the generated form of Luvah.This crucial idea is■ ot found in T力θ Bο ο″っF」77izι η,as is clear from the fact that the poe■1, although meant to be the first book of a longer study of the Fall and probably 」udgment,came to a dead end because of the lack of this crucial identity of Orc. This moment of inspiration is,in my view,expressed in 4物 を打θα.2 The COmpletion of the myth of Orc and its coHapse is found only in the Preludiunl ofス 滅 θα.This rise and fa1l of the myth of Orc can be seen as reflecting the formation and -

The Memory of the American and French Revolutions in William Blake's

University of Bucharest Review Vol. III/2013, no. 1 (new series) Cultures of Memory, Memories of Culture Ruxanda Topor* THE MEMORY OF THE AMERICAN AND FRENCH REVOLUTIONS IN WILLIAM BLAKE’S AMERICA: A PROPHECY AND EUROPE: A PROPHECY Keywords: Blake; memory; revolution; America; Europe; France; England. Abstract: The French and American Revolutions were radical historical events of paramount significance for the subsequent fate of the two continents- Europe and America. They entailed deep social changes and fostered revolutionary ideas of freedom and equality that challenged the old hierarchies. William Blake, the English Romantic poet, lived amidst the turmoil and excitement brought by these mnemonically outstanding events- his lifespan comprised both revolutions. This paper sets out to explore his stance towards the French and American Revolutions in two of his prophetic books, Europe: A Prophecy and America: A Prophecy. The books reveal a harmonious blending of historical fact with mythological figures, such as Orc, the outstanding character that represents the revolutionary spirit. In addition, the presence of intertextuality in the poems, besides attesting to the pervasiveness and importance of these cultural upheavals at the time, authorizes subjective poetic memory and contributes to meaning-making, by reference to other works or documents dwelling on similar subjects. Blake recalls the images of noteworthy figures that played a major role in the revolutions; he also invokes sites of memory and scenes of war. Last but not least, the poet calls forth the emotional states dominating the people from both continents. Being an Englishman living in a monarchy, Blake stresses out throughout the books England’s attitude and reaction towards the French and American Revolutions, which shows his high concern for the fate of his country. -

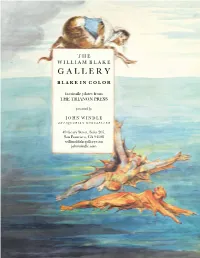

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected]