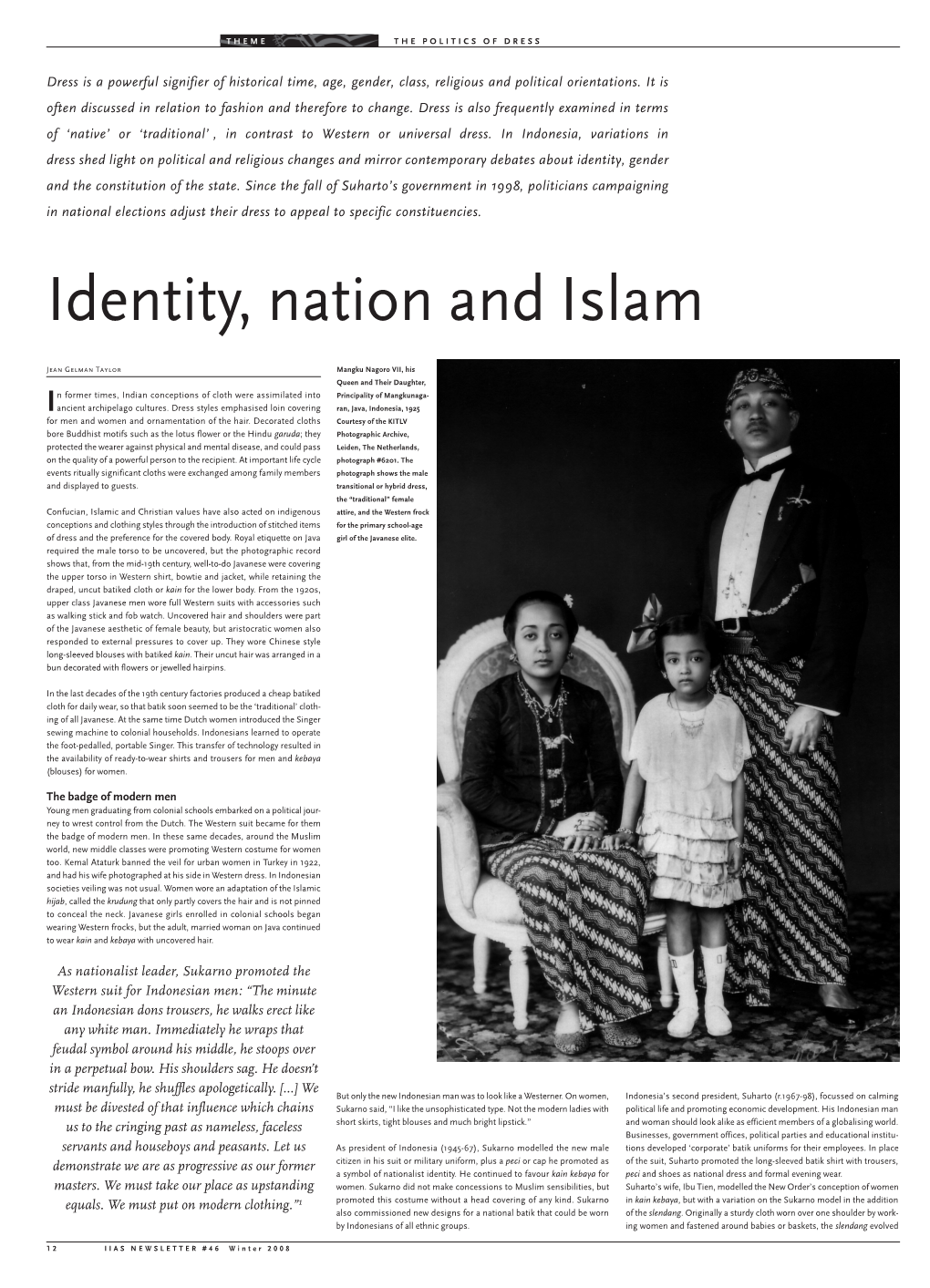

Identity, Nation and Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

His Excellency Mr. Joko Widodo, President of Indonesia

REMARKS PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA H.E. JOKO WIDODO AT 77TH SESSION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC (UNESCAP) MONDAY, 26 APRIL 2021 Page 1 of 4 Executive Secretary of the UNESCAP, Armida Alisjahbana, and all Delegates, 1. The COVID-19 Pandemic has shown us ➔ of the weakness of health infrastructures at the national, regional, and global levels. ➔ And how fragile our economy is from external shocks. 2. Therefore together, we must reflect upon ourselves and correct our course. 3. The Asia and Pacific region must soon come out from the pandemic and become stronger. 4. Recover together…recover stronger. 5. Allow me to share some thoughts. 6. First… we must expand investment in strengthening regional health resilience. 7. The region’s health expenditures are still low. ➔ In South Asia, for instance, at only 3.48% of the GDP, while East Asia and the Pacific at 6.67%. ➔ Compared to in Latin America 7.96%, in the European Union 9.85%, and in the United States 16.89%. 8. This needs to be corrected. 9. UNESCAP must become the catalyst in strengthening the region’s health infrastructure, through … ➔ Enhancing the quality of health personnel Page 2 of 4 ➔ Collaborating in health, pharmaceutical, vaccines, and medical raw materials industries … and ➔ research and technology in the health sector 10. The capacity for pandemic early warning in the region must also be strengthened. 11. Second… we have to adapt towards economic recovery 12. Investment on digital-based economy must be scaled up. 13. Innovation to support safe tourism must be undertaken. -

SUSILO BAMBANG YUDHOYONO and HIS GENERALS by Leonard C

SUSILO BAMBANG YUDHOYONO AND HIS GENERALS by Leonard C. Sebastian EXECUTIVE SUMMARY a civilian government where the to provide the military with an special position of the armed forces adequate budget. Third, if a The Indonesian National Military allowed it autonomy to reserve civilian government is unable to (TNI, Tentera Nasional Indonesia) power enabling the TNI to play a maintain national stability and unity. may no longer be the most dominant leading role in politics or mediate Particularly in the third scenario, player in Indonesian politics but between political contenders. The the likelihood that the TNI will has pragmatically incorporated a TNI’s preeminent position was a temporarily re-enter the political strategy that enables it to play a reflection of its special entitlement arena in partnership with other like- significant “behind the scenes” role. owing to its role in the war of minded social and political forces The situation in Indonesia today independence (1945-48) where its to stabilize national politics cannot has closer parallels with the state defence of the Republic ensured be discounted. The mindset of of civil military relations in Germany that the returning Dutch colonialists the officer corps has not changed between the two World Wars or would not be able to subdue the drastically despite the abolition France in 1958.1 In analysing the TNI independence movement by military of its Dual Function role in 2000. relationship with the Yudhoyono means. There remains a deep contempt for presidency, this paper argues that civilian rule and a belief that only the Dr Yudhoyono enjoys the loyalty and The situation in Indonesia since TNI is capable of rising above the trust of the TNI elite. -

1 SUMMARY the Shibori, Batik and Ikat Techniques Are Known As Resist

SIMBOL ŞI TEHNICĂ ARHAICĂ-RAPEL ÎN CREAłIA CONTEMPORANĂ BITAY ECATERINA 1 SUMMARY The Shibori, Batik and Ikat techniques are known as resist dyeing techniques. „Shibori” is actually an old name of the Tie-dye technique, a widespread expression in the hippie communities of the 60’s – 70’s period, when this technique had a great success also among the fashion designers, making a spectacular comeback, after a long period of sporadic isolation in certain areas of the world, especially in Japan, Africa and South America. The first textiles found by archaeologists are so old that we may say that world history could be read in the nations’ textiles. The rise of the civilizations and the fall of the empires are woven and printed on the scarves and the shrouds of the great conquests main characters. Archaeological diggings revealed signs of these traditions of 5000 years old. Religion, traditions, myths, superstitions and rituals are closely related to the textiles belonging to many nations of Eastern Asia, Asia Minor, and of the Pacific Islands, their aesthetic value being, more than once, secondary. CHAPTER 1 THE SHIBORI TECHNIQUE The origin of the word “Shibori” is the verb “shiboru” which means to wring, to twist, to press. Even if “shibori” refers to a particular group of resist dyeings, the word’s origin suggests the cloth manipulation process and it can comprise modern methods of dyeing which involve the same type of cloth treatment, possibly without pigments or treatment with pigments applied by using totally different methods than the ancient ones. Shibori can be divided in many ways: according to the areas where it is used, such as Japan, China, India, Africa, Indonesia, South America or according to the details usesd in the technique. -

Batik Wax Instructions

Instructions Batik Wax Batik: A History Although its exact origin is uncertain, the earliest known batiks were discovered in Egyptian tombs dating back to the 4th century BCE. Wax-resist techniques were probably developed independently by disparate cultures throughout the ancient world. By the seventh century AD, patterning fabric using resists such as wax was a widespread practice throughout Asia and Africa and was perhaps most fully developed as an artform in Indonesia, where batik predates written records. By the thirteenth century, it became a highly respected art form and pastime for the women of Java and Bali, as recognizable motifs, patterns and colors became signifiers of one’s family and geographical area. Distinct styles and traditions proliferated and spread with the exchange of cultures through trade and exploration (see the “inland” and “coastal” batiks of Java, for instance — the two traditions couldn’t be more different). In the seventeenth century, as the world grew smaller, batik was introduced in Holland and other parts of Europe, where it became increasingly fashionable. Europeans and Americans traveling and living in the East encountered the ancient process and brought it back to their homelands — and spread it to colonies far away — where new traditions of batik branched out. Today, art schools across the United States and Europe offer batik courses as an essential part of their textile curricula. For more tips and techniques see www.jacquardproducts.com JACQUARD PRODUCTS Manufactured by Rupert, Gibbon & Spider, Inc. Healdsburg, CA 95448 | www.jacquardproducts.com | 800.442.0455 Batik Instructions Preparing and designing your fabric All new fabrics must be washed with hot soapy water, rinsed and dried to remove factory-applied sizings which may inhibit color penetration. -

Vice President's Power and Role in Indonesian Government Post Amendment 1945 Constitution

Al WASATH Jurnal Ilmu Hukum Volume 1 No. 2 Oktober 2020: 61-78 VICE PRESIDENT'S POWER AND ROLE IN INDONESIAN GOVERNMENT POST AMENDMENT 1945 CONSTITUTION Roziqin Guanghua Law School, Zhejiang University, China Email: [email protected] Abstract Politicians are fighting over the position of Vice President. However, after becoming Vice President, they could not be active. The Vice President's role is only as a spare tire. Usually, he would only perform ceremonial acts. The exception was different when the Vice President was Mohammad Hata and Muhammad Jusuf Kalla. Therefore, this paper will question: What is the position of the President in the constitutional system? What is the position of the Vice President of Indonesia after the amendment of the 1945 Constitution? Furthermore, how is the role sharing between the President and Vice President of Indonesia? This research uses the library research method, using secondary data. This study uses qualitative data analysis methods in a prescriptive-analytical form. From the research, the writer found that the President is assisted by the Vice President and ministers in carrying out his duties. The President and the Vice President work in a team of a presidential institution. From time to time, the Indonesian Vice President's position has always been the same to assist the President. The Vice President will replace the President if the President is permanently unavailable or temporarily absent. With the Vice President's position who is directly elected by the people in a pair with the President, he/she is a partner, not subordinate to the President. -

Textile Printing

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 ISP 1004 TEXTILE PRINTING This report is sponsored by the Importer Support Program and written to address the technical needs of product sourcers. © 2003 Cotton Incorporated. All rights reserved; America’s Cotton Producers and Importers. INTRODUCTION The desire of adding color and design to textile materials is almost as old as mankind. Early civilizations used color and design to distinguish themselves and to set themselves apart from others. Textile printing is the most important and versatile of the techniques used to add design, color, and specialty to textile fabrics. It can be thought of as the coloring technique that combines art, engineering, and dyeing technology to produce textile product images that had previously only existed in the imagination of the textile designer. Textile printing can realistically be considered localized dyeing. In ancient times, man sought these designs and images mainly for clothing or apparel, but in today’s marketplace, textile printing is important for upholstery, domestics (sheets, towels, draperies), floor coverings, and numerous other uses. The exact origin of textile printing is difficult to determine. However, a number of early civilizations developed various techniques for imparting color and design to textile garments. Batik is a modern art form for developing unique dyed patterns on textile fabrics very similar to textile printing. Batik is characterized by unique patterns and color combinations as well as the appearance of fracture lines due to the cracking of the wax during the dyeing process. Batik is derived from the Japanese term, “Ambatik,” which means “dabbing,” “writing,” or “drawing.” In Egypt, records from 23-79 AD describe a hot wax technique similar to batik. -

Pergub DIY Tentang Penggunaan Pakaian Adat Jawa Bagi

SALINAN GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA PERATURAN GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA NOMOR 87 TAHUN 2014 TENTANG PENGGUNAAN PAKAIAN TRADISIONAL JAWA YOGYAKARTA BAGI PEGAWAI PADA HARI TERTENTU DI DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA, Menimbang : a. bahwa salah satu keistimewaan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta sebagaimana ditetapkan dalam Pasal 7 ayat (2) Undang-undang Nomor 13 Tahun 2012 tentang Keistimewaan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta adalah urusan kebudayaan yang perlu dilestarikan, dipromosikan antara lain dengan penggunaan Pakaian Tradisional Jawa Yogyakarta; b. bahwa dalam rangka melestarikan, mempromosikan dan mengembangkan kebudayaan salah satunya melalui penggunaan busana tradisional Jawa Yogyakarta, maka perlu mengatur penggunaan Pakaian Tradisional pada hari tertentu di Lingkungan Pemerintah Daerah Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta; c. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a, huruf dan b perlu menetapkan Peraturan Gubernur tentang Penggunaan Pakaian Tradisional Jawa Yogyakarta Bagi Pegawai Pada Hari Tertentu Di Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta; Mengingat : 1. Pasal 18 ayat (6) Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia 1945; 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 3 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah Istimewa Jogjakarta (Berita Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1950, Nomor 3) sebagaimana telah diubah terakhir dengan Undang-Undang Nomor 9 Tahun 1955 tentang Perubahan Undang-Undang Nomor 3 Tahun 1950 jo Nomor 19 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah Istimewa Jogjakarta (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1955, Nomor 43, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 827); 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 13 Tahun 2012 tentang Keistimewaan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2012, Nomor 170, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5339); 4. Undang-Undang Nomor 5 Tahun 2014 tentang Aparatur Sipil Negara (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2014 Nomor 6, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5494); 5. -

Redalyc.Democratization and TNI Reform

UNISCI Discussion Papers ISSN: 1696-2206 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Marbun, Rico Democratization and TNI reform UNISCI Discussion Papers, núm. 15, octubre, 2007, pp. 37-61 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76701504 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 15 (Octubre / October 2007) ISSN 1696-2206 DEMOCRATIZATIO A D T I REFORM Rico Marbun 1 Centre for Policy and Strategic Studies (CPSS), Indonesia Abstract: This article is written to answer four questions: what kind of civil-military relations is needed for democratization; how does military reform in Indonesia affect civil-military relations; does it have a positive impact toward democratization; and finally is the democratization process in Indonesia on the right track. Keywords: Civil-military relations; Indonesia. Resumen: Este artículo pretende responder a cuatro preguntas: qué tipo de relaciones cívico-militares son necesarias para la democratización; cómo afecta la reforma militar en Indonesia a las relaciones cívico-militares; si tiene un impacto positivo en la democratización; y finalmente, si el proceso de democratización en Indonesia va por buen camino. Palabras clave: relaciones cívico-militares; Indonesia. Copyright © UNISCI, 2007. The views expressed in these articles are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNISCI. Las opiniones expresadas en estos artículos son propias de sus autores, y no reflejan necesariamente la opinión de U*ISCI. -

Shifting of Batik Clothing Style As Response to Fashion Trends in Indonesia Tyar Ratuannisa¹, Imam Santosa², Kahfiati Kahdar3, Achmad Syarief4

MUDRA Jurnal Seni Budaya Volume 35, Nomor 2, Mei 2020 p 133 - 138 P- ISSN 0854-3461, E-ISSN 2541-0407 Shifting of Batik Clothing Style as Response to Fashion Trends in Indonesia Tyar Ratuannisa¹, Imam Santosa², Kahfiati Kahdar3, Achmad Syarief4 ¹Doctoral Study Program of Visual Arts and Design, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jl. Ganesa 10 Bandung, Indonesia 2,3,4Faculty of Visual Arts and Design, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jl. Ganesa 10 Bandung, Indonesia. [email protected] Fashion style refers to the way of wearing certain categories of clothing related to the concept of taste that refers to a person’s preferences or tendencies towards a particular style. In Indonesia, clothing does not only function as a body covering but also as a person’s style. One way is to use traditional cloth is by wearing batik. Batik clothing, which initially took the form of non -sewn cloth, such as a long cloth, became a sewn cloth like a sarong that functions as a subordinate, evolved with the changing fashion trends prevailing in Indonesia. At the beginning of the development of batik in Indonesia, in the 18th century, batik as a women’s main clothing was limited to the form of kain panjang and sarong. However, in the following century, the use of batik cloth- ing became increasingly diverse as material for dresses, tunics, and blouses.This research uses a historical approach in observing batik fashion by utilizing documentation of fashion magazines and women’s magazines in Indonesia. The change and diversity of batik clothing in Indonesian women’s clothing styles are influenced by changes and developments in the role of Indonesian women themselves, ranging from those that are only doing domestic activities, but also going to school, and working in the public. -

IFES Faqs on Elections in Indonesia: 2019 Concurrent Presidential And

Elections in Indonesia 2019 Concurrent Presidential and Legislative Elections Frequently Asked Questions Asia-Pacific International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive | Floor 10 | Arlington, VA 22202 | www.IFES.org April 9, 2019 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? ................................................................................................................................... 1 Who are citizens voting for? ......................................................................................................................... 1 What is the legal framework for the 2019 elections? .................................................................................. 1 How are the legislative bodies structured? .................................................................................................. 2 Who are the presidential candidates? .......................................................................................................... 3 Which political parties are competing? ........................................................................................................ 4 Who can vote in this election?...................................................................................................................... 5 How many registered voters are there? ....................................................................................................... 6 Are there reserved seats for women? What is the gender balance within the candidate list? .................. -

Rizal Ramli Interviewer

An initiative of the National Academy of Public Administration, and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and the Bobst Center for Peace and Justice, Princeton University Oral History Program Series: Governance Traps Interview no.: C7 Interviewee: Rizal Ramli Interviewer: Matthew Devlin Date of Interview: 15 July 2009 Location: Jakarta Indonesia Innovations for Successful Societies, Bobst Center for Peace and Justice Princeton University, 83 Prospect Avenue, Princeton, New Jersey, 08544, USA www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties Use of this transcript is governed by ISS Terms of Use, available at www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties Innovations for Successful Societies Series: Governance Traps Oral History Program Interview number: C-7 ______________________________________________________________________ DEVLIN: Today is July 15th, 2009, I’m here in Jakarta, Indonesia with Dr. Rizal Ramli. Dr. Ramli headed the nation’s State Logistics Agency and most notably was Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs under the administration of then President Abdurrahman Wahid and also Minister of Finance among other positions in politics here in Indonesia. Dr. Ramli, thank you for joining me. If I could, could we possibly begin by you giving us a sense of the environment here in Indonesia at this transitional point between the longstanding new order and the post Suharto era? RAMLI: The Suharto regime had been in power for such a long time, more than 32 years before it fell. The longer he stayed, the more authoritarian the nature of his regime. But the core of his political support was essentially the armed forces, the bureaucracy, and of course the ruling party which is Golkar. So it is interesting to note for Suharto to go there should be an underlying shift in the perception of the key player in Indonesian politics, especially the army towards Suharto. -

The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance

Policy Studies 23 The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Marcus Mietzner East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the theme of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American understanding of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Policy Studies 23 ___________ The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance _____________________ Marcus Mietzner Copyright © 2006 by the East-West Center Washington The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance by Marcus Mietzner ISBN 978-1-932728-45-3 (online version) ISSN 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C.