Reformation England and the Performance of Wonder: Automata Technology and the Transfer of Power from Church to State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering King Charles I: History, Art and Polemics from the Restoration to the Reform Act T

REMEMBERING KING CHARLES I: HISTORY, ART AND POLEMICS FROM THE RESTORATION TO THE REFORM ACT T. J. Allen Abstract: The term Restoration can be used simply to refer to the restored monarchy under Charles II, following the Commonwealth period. But it can also be applied to a broader programme of restoring the crown’s traditional prerogatives and rehabilitating the reign of the king’s father, Charles I. Examples of this can be seen in the placement of an equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross and a related poem by Edmund Waller. But these works form elements in a process that continued for 200 years in which the memory of Charles I fused with contemporary constitutional debates. The equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross, produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur c1633 and erected in 1675. Photograph: T. J. Allen At the southern end of Trafalgar Square, looking towards Whitehall, stands an equestrian statue of Charles I. This is set on a pedestal whose design has been attributed to Sir Christopher Wren and was carved by Joshua Marshall, Master Mason to Charles II. The bronze figure was originally commissioned by Richard Weston (First Earl of Portland, the king’s Lord High Treasurer) and was produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur in the early 1630s. It originally stood in 46 VIDES 2014 the grounds of Weston’s house in Surrey, but as a consequence of the Civil War was later confiscated and then hidden. The statue’s existence again came to official attention following the Restoration, when it was acquired by the crown, and in 1675 placed in its current location. -

Tethys Festival As Royal Policy

‘The power of his commanding trident’: Tethys Festival as royal policy Anne Daye On 31 May 1610, Prince Henry sailed up the River Thames culminating in horse races and running at the ring on the from Richmond to Whitehall for his creation as Prince of banks of the Dee. Both elements were traditional and firmly Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester to be greeted historicised in their presentation. While the prince is unlikely by the Lord Mayor of London. A flotilla of little boats to have been present, the competitors must have been mem- escorted him, enjoying the sight of a floating pageant sent, as bers of the gentry and nobility. The creation ceremonies it were, from Neptune. Corinea, queen of Cornwall crowned themselves, including Tethys Festival, took place across with pearls and cockleshells, rode on a large whale while eight days in London. Having travelled by road to Richmond, Amphion, wreathed with seashells, father of music and the Henry made a triumphal entry into London along the Thames genius of Wales, sailed on a dolphin. To ensure their speeches for the official reception by the City of London. The cer- carried across the water in the hurly-burly of the day, ‘two emony of creation took place before the whole parliament of absolute actors’ were hired to play these tritons, namely John lords and commons, gathered in the Court of Requests, Rice and Richard Burbage1 . Following the ceremony of observed by ambassadors and foreign guests, the nobility of creation, in the masque Tethys Festival or The Queen’s England, Scotland and Ireland and the Lord Mayor of Lon- Wake, Queen Anne greeted Henry in the guise of Tethys, wife don with representatives of the guilds. -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Cover Hubert Le Sueur Hercules and Telephus.Indd

benjamin proust fine art limited london benjamin proust fine art limited london attributed to HUBERT LE SUEUR Paris, 1580–1658 hercules and telephus circa 1630 Bronze 39.4 x 15.9 x 12.4 cm Inventory mark ‘8’ in red paint on lion skin tail provenance Most probably, François Le Vau (1613–1676), ‘Maison du Centaure’, 45 Quai de Bourbon, Paris, until his death; Most probably, Louis, Grand Dauphin de France (1661–1711), Château de Versailles, from at least 1689 and until his death, when sold; Most probably, Jean-Baptiste, Count du Barry (1723–1794), Paris; His sale, 21 November 1774, lot 142; Noble private collection, Provence, France, until 2017 comparative literature F. Souchal, Les Frères Coustou, Paris, 1980 G. Bresc-Bautier, ‘L’activité parisienne d’Hubert Le Sueur sculpteur du roi (connu de 1596 à 1658)’, in Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, 1985, pp. 35–54 C. Avery, ‘Hubert Le Sueur, the ‘Unworthy Praxiteles’ of King Charles I’, in Studies in European Sculpture II, London, 1988, pp. 145–235 J. Chlibec, ‘Small Italian Renaissance Bronzes in the Collection of the National Gallery in Prague’, in Bulletin of the National Gallery in Prague, III-IV (1993–94), pp. 36–52 A. Gallottini (ed.), ‘Philippe Thomassin: Antiquarum Statuarum Urbis Romae Liber Primus (1610–1622)’, in Bollettino d’Arte, 1995, pp. 21–23 S. Castelluccio, ‘La Collection de bronzes du Grand Dauphin’, in Curiosité: Édutes d’histoire de l’art en l’honneur d’Antoine Schnapper, Paris, 1998, pp. 355–63 S. Baratte, G. Bresc-Bautier et al., Les Bronzes de la Couronne, exh. -

Representations of the Marine in Jacobean Drama and Visual Culture

‘A Sea-Change’: Representations of the Marine in Jacobean Drama and Visual Culture By Maria Shmygol Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy December 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ List of Illustrations ii Acknowledgements iv Note on Presentation v INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE The Marine in English and Scottish Entertainments pre 1603 36 CHAPTER TWO Civic Pageantry: Marine Metaphor and Urban Location 69 CHAPTER THREE Seafaring and Maritime Endeavour 100 CHAPTER FOUR Strange Fish 135 CHAPTER FIVE Representations of the Marine in the Jacobean Court Masque 179 CONCLUSION 232 ILLUSTRATIONS 240 APPENDIX: Transcription and translation of Histoire tragique, & espouvantable […] d’un monstre marin (1616) 256 BIBLIOGRAPHY 263 i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS _____________________________________________________ Fig. 1. Detail from a hand-coloured woodcut depicting the Elvetham Entertainment (1591) as it appears in the revised second quarto of the printed account. Fig. 2. Plate from John Gough Nichols, ed., The Fishmongers’ Pageant on Lord Mayor's Day, 1616 Fig. 3. Woodcut from A True Relation, of the Lives and Deaths of two Most Famous English pyrats, Purser, and Clinton (London, 1639). Fig 4. Sea monster tableau vivant from Sebastian Münster’s Comographia Universalis (Basel, 1559). Fig. 5. Detail from Olaus Magnus, Carta Marina (Rome, 1572). Fig. 6. Title-page of A Most Strange and True Report of a Monsterous Fish, that Appeared in the forme of a Woman, from her Waist Upwardes (London, 1603). Fig. 7. From Conrad Gesner, Conradi Gesneri Medici Tigurini Historiae Animalium, 5 vols (Zurich, 1551-87), IV (1558). -

ROYAL COLLECTION STUDIES 2016 Reading List

ROYAL COLLECTION STUDIES 2016 Reading list There is a vast literature on the Royal Collection, the royal palaces and the British monarchy. The aim here is to provide references to the works which will be of most use both before and after the course. The first part contains some widely available titles which should ideally be read in advance. The second, longer part is a guide for those who wish to pursue subjects in more depth afterwards. A lengthy bibliography can also be found in the exhibition catalogue Royal Treasures (2002/2008). Titles marked with an asterisk* are current Royal Collection publications, distributed by Thames & Hudson and available from [email protected] or from the on- site shops. See also the Royal Collection website/shop for many of these titles www.royalcollection.org.uk and www.royalcollectionshop.co.uk. PART ONE (Before the course) General titles Christopher Lloyd The Paintings in the Royal Collection London, 1999 Oliver Millar The Queen’s Pictures, The Story of the Royal Collection from Henry VIII to Elizabeth II London, 1977 J.H. Plumb & H. Weldon Royal Heritage. The Story of Britain’s Royal Builders and Collectors London, BBC, 1977 The book which accompanied the BBC television series celebrating the Silver Jubilee, and still a useful tour d’horizon of the collection in its settings. Geoffrey de Bellaigue et al Carlton House: the past glories of George IV’s palace Exh. cat., The Queen’s Gallery, London, 1991 A preliminary read through this authoritative work on Carlton House, perhaps in conjunction with the following title, will prove very helpful at several points in the course. -

Benjamin Proust Fine Art Limited London

london fall 2018 fall TEFAF NEW YORK NEW YORK TEFAF fine art limited benjamin proust benjamin TEFAF NEW YORK 2018 BENJAMIN PROUST LONDON benjamin proust fine art limited london TEFAF NEW YORK fall 2018 CONTENTS important 1. ATTRIBUTED TO LUPO DI FRANCESCO VIRGIN AND CHILD european 2. SIENA, EARLY 14TH CENTURY sculpture SEAL OF THE COMMUNAL WHEAT OF SIENA 3. FLORENCE, LATE 15TH CENTURY BUST OF A BOY 4. PIERINO DA VINCI TWO CHILDREN HOLDING A FISH 5. ATTRIBUTED TO WILLEM VAN TETRODE BUST OF TIBERIUS 6. FLORENCE OR ROME, FIRST HALF 17TH CENTURY FLORA FARNESE 7. ATTRIBUTED TO HUBERT LE SUEUR HERCULES AND TELEPHUS antiquities 8. KAVOS, EARLY CYCLADIC II LYRE-SHAPED HEAD & modern 9. GREEK, LATE 5TH CENTURY BC drawings ATTIC BLACK-GLAZED PYXIS 10. IMPERIAL ROMAN OIL LAMP 11. AUGUSTE RODIN FEMME NUE ALLONGÉE 12. AUGUSTE RODIN NAKED WOMAN IN A FUR COAT 13. PIERRE BONNARD PAYSAGE DE VERNON benjamin proust Having first started at the Paris flea market, Benjamin Proust trained with international-level art dealers, experts and auctioneers in France and Belgium, setting up his own gallery in Brussels in 2008. In 2012, Benjamin moved his activity to New Bond Street, in the heart of Mayfair, London’s historic art district, where it has been located ever since. A proud sponsor of prominent British institutions such as The Wallace Collection and The Courtauld Gallery in London, Benjamin Proust Fine Art focuses on European sculpture and works of art, with a particular emphasis on bronzes and the Renaissance. Over the years, our meticulous sourcing, in-depth research, and experience in solving provenance issues, all conducted with acknowledged honesty and professionalism, have been recognized by a growing number of major international museums, with whom long-standing relationships have been established. -

Contents of Previous Walpole Society Volumes

CONTENTS OF PREVIOUS WALPOLE SOCIETY VOLUMES Abbo$, John White, of Exeter . XIII. 67 Abercorn, Lord, Le$ers from Uvedale Price . LXVIII (enCre volume) Adams, C. Kingsley, and W. S. Lewis, The Portraits of Horace Walpole . XLII. 1 Alexander, David, George Vertue as an Engraver . LXX. 207 Allen, Derek, Thomas Simon’s Sketch-Book . XXVII. 13 Althorp, A Catalogue of Pictures . XLV (enCre volume) Anderson, Jaynie, The Travel Diary of OBo Mündler . LI (enCre volume) Andrew, Patricia R., Jacob More: Biography and a Checklist of Works . LV. 105 Andrews, H. C., A Lost Monument by Nicholas Stone . VIII. 127 ‘Arte of Limning’, Nicholas Hilliard’s . I. 1 Ashfield, Edmund . III. 83 Avery, Charles, Hubert Le Sueur, ‘the unworthy Praxiteles of King Charles I’ . XLVIII. 135 Avery-Quash, Susanna, The Travel Notebooks of Sir Charles Eastlake . LXXIII (enCre volume) Baker, Audrey, Lewes Priory and the Early Group of Wall PainSngs in Sussex . XXXI. 1 Baker, C. H. Collins, Notes on Edmund Ashfield . III. 83 and L. O’Malley, Reynolds’s First Portrait of Keppel . I. 83 Baker, Malcolm, et al., The Ledger of Sir Francis Chantrey, R.A., at the Royal Academy, 1809–1841 . LVI (enCre volume) Barcheston Tapestries . XIV. 27 Bardwell, Thomas, of Bungay, ArCst and Author 1704–1767, with a Checklist of Works . XLVI. 91 A Notebook of Portrait ComposiCons by . LIII. 181 Barker, Elizabeth E., Documents relaSng to Joseph Wright ‘of Derby’ (1734–97) . LXXI. 1 Ba$en, M. I., The Architecture of Dr. Robert Hooke, F.R.S. XXV. 83 Beaumont, Sir George and Lady, Le$ers from Uvedale Price . -

Katharine Esdaile Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8x63sn4 No online items Katharine Esdaile Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by John Houlton, Marilyn Olsen, Catherine Wehrey, and Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © November 2016 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Katharine Esdaile Papers: Finding mssEsdaile 1 Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Katharine Esdaile Papers Dates (inclusive): 1845-1961 Bulk dates: 1900-1950 Collection Number: mssEsdaile Collector: Esdaile, Katharine Ada, 1881-1950 Extent: 101 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of English art historian Katharine Ada Esdaile (1881-1950). Much of the collection relates to her research of British monumental sculpture. Notably the collection includes more than 600 chiefly pre-World War II visitor booklets and pamphlets produced locally by British churches and approximately 3500 photographs taken or collected by Esdaile of sculpture, often funerary monuments in English churches. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Bibliography Sources for Further Reading May 2011 National Trust Bibliography

Bibliography Sources for further reading May 2011 National Trust Bibliography Introduction Over many years a great deal has been published about the properties and collections in the care of the National Trust, yet to date no single record of those publications has been established. The following Bibliography is a first attempt to do just that, and provides a starting point for those who want to learn more about the properties and collections in the National Trust’s care. Inevitably this list will have gaps in it. Do please let us know of additional material that you feel might be included, or where you have spotted errors in the existing entries. All feedback to [email protected] would be very welcome. Please note the Bibliography does not include minor references within large reference works, such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, or to guidebooks published by the National Trust. How to use The Bibliography is arranged by property, and then alphabetically by author. For ease of use, clicking on a hyperlink will take you from a property name listed on the Contents Page to the page for that property. ‘Return to Contents’ hyperlinks will take you back to the contents page. To search by particular terms, such as author or a theme, please make use of the ‘Find’ function, in the ‘Edit’ menu (or use the keyboard shortcut ‘[Ctrl] + [F]’). Locating copies of books, journals or specific articles Most of the books, and some journals and magazines, can of course be found in any good library. For access to rarer titles a visit to one of the country’s copyright libraries may be necessary. -

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

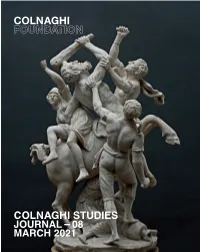

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

A Set of Four English Alabaster Swans

Nicholas Stone (1586 - 1647) A set of four English alabaster swans Alabaster 56.5 cm (22 ¼ in.) high 66.7 cm (26 ¼ in.) wide 39.5 cm (15 ½ in.) deep These four swans represent an exceptional survival of secular genre sculpture from the 17th century, a period when an indigenous English school of sculpture was virtually non-existent. A tradition of alabaster carving of international stature had been well established in England since the Middle Ages, thanks to large quarries in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, but the upheavals of the Reformation and dynastic conflicts in the mid-16th century effectively eradicated major ecclesiastic and courtly patronage of the arts for several generations, and until the 18th century English sculpture was ‘very largely a question of tombs and monuments’ (Whinney, p.26). During the Jacobean and Carolean periods most English sculpture was therefore produced by stonemasons rather than trained artists, and patrons with higher pretentions for their commissions would normally turn to foreign artists, such as the French expatriate Hubert Le Sueur (c.1580-1658) who became official court sculptor to Charles I. The one notable exception to this penury of native-born talent was Nicholas Stone, born in Exeter and apprenticed at a young age to Isaac James, a Dutch-born stonemason in Southwark. In 1606 he travelled to Amsterdam to work for the Dutch sculptor Hendrik de Keyser (1567-1621), where he spent seven years, marrying de Keyser’s daughter and probably building the portico of the Westerkerk in Amsterdam. Upon his return to London he established a thriving workshop in Covent Garden providing funerary monuments.