“Micro” Finance for Small-Scale Irrigation in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Review of Lessons Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Pay TV Fragments

Global pay TV fragments The top 503 pay TV operators will reach 853 million subscribers from the 1.02 billion global total by 2026. The top 50 operators accounted for 64% of the world’s pay TV subscribers by end-2020, with this proportion dropping to 62% by 2026. Pay TV subscribers by operator ranking (million) 1200 1000 143 165 38 45 800 74 80 102 102 600 224 215 400 200 423 412 0 2020 2026 Top 10 11-50 51-100 101-200 201+ Excluded from report The top 50 will lose 20 million subscribers over the next five years. However, operators beyond the top 100 will gain subscribers over the same period. Simon Murray, Principal Analyst at Digital TV Research, said: “Most industries consolidate as they mature. The pay TV sector is doing the opposite – fragmenting. Most of the subscriber growth will take place in developing countries where operators are not controlled by larger corporations.” By end-2020, 13 operators had more than 10 million pay TV subscribers. China and India will continue to dominate the top pay TV operator rankings, partly as their subscriber bases climb but also due to the US operators losing subscribers. Between 2020 and 2026, 307 of the 503 operators (61%) will gain subscribers, with 13 showing no change and 183 losing subscribers (36%). In 2020, 28 pay TV operators earned more than $1 billion in revenues, but this will drop to 24 operators by 2026. The Global Pay TV Operator Forecasts report covers 503 operators with 726 platforms [132 digital cable, 116 analog cable, 279 satellite, 142 IPTV and 57 DTT] across 135 countries. -

ETB 2013 V2:Layout 1

Reader’s Digest Trusted Brands Survey 2013 Contents Page No: Overview 3 How we award Trusted Brand status 7 The Trusted Brand logo and guidelines for its usage 8 Results - Brands: 20 common categories 9 Most nominated brands across Europe 10 All winners by country and category – share of vote 12 Comparison of winners by category – past 5 years 14 The local categories – winning brands 21 Results – Confidence and Trust: Professions 25 Government Policies 31 Criteria of trust 36 Trust and purchase 42 Appendix i. Response rate by country 2013 v 2012 46 ii. Respondent base 2009 – 2013 47 iii. Respondents by category by country 48 iv. Respondent profile – all countries 49 v. Respondent profile by country 50 vi. Population weightings 51 Sample questionnaire 55 Reader’s Digest circulation and readership by country 59 Contacts by country 60 www.rdtrustedbrands.com 2 Reader’s Digest Trusted Brands 2013 An overview About the survey • Reader’s Digest European Trusted Brands is now in its 13th year, it was first published in 2001. • Fieldwork for this study is conducted annually and the results are available (free of charge) from www.rdtrustedbrands.com • In order to allow for tracking over time every effort is made to retain consistency in methodology, content and presentation of data. • Research was conducted in 11 languages across 12 European countries. • Croatia and Sweden did not participate in 2013. Fieldwork was conducted in Austria but didn’t produce an acceptable base for detailed analysis of the brand results. • The primary focus of the study is to find out which brands Europeans trust the most. -

Diapositiva 1

July 14th, 2016 Company Update Rating: Colombia, Equities Buy Industry: ETB Telecoms & Media Fever for fiber After the strong performance in the name since our upgrade to BUY in Oct-15 (total return of +20.4% compared to 8.1% the COLCAP), we are setting our 2016 TP at COP 720 with a BUY Company Data recommendation. The new TP and rating consider a successful Ticker etb cb sale process of ETB. Price (COP) 590 . Sale process ahead looks promising. ETB is going through a LTM Range (COP) 485 - 619 process (Law 226) to sell the 86.6% stake of the District in the Target 720 company. The Bogota Council approved the sale process on Ex pected Return 22.0% May 30th as part of Bogota’s Development Plan, and according to the management, the sale to the general public should be Market Cap (USD mn) 714 ready by the second half of 2017. Shares Outstanding (mn) 3,551 Free Float 13.0% . Strategic shift in the company’s outlook. The prior administration invested 2 COP tn in the modernization of ETB’s ADTV (USD mn) 0.3 infrastructure, which allowed the company to have a stronger stream of income in business lines other than copper networks. This gives the company a new competitive outlook. ADTV and Performance . The potential entry of a strategic investor should be value 130 6 enhancing for current shareholders. We consider that with a strategic and experienced majority shareholder, ETB could see 120 5 important improvements in three fronts i) commercial strategy, 110 improving market shares, ii) efficiency, improving margins and 4 100 iii) corporate governance, allowing it to carry on its strategy 3 90 consistently in the long term. -

Two-Thirds of Pay TV Operators Will Gain Subs

Two-thirds of pay TV operators will gain subs Two-thirds of the world’s pay TV operators will gain subscribers between 2019 and 2025. Covering 502 operators across 135 countries, the Global Pay TV Operator Forecasts report estimates that 59% will also increase their revenues over the same period. Share of pay TV subscribers by operator ranking (million) 100% 38 48 90% 74 80 80% 104 106 70% 225 60% 225 50% 40% 30% 460 449 20% 10% 0% 2019 2025 Top 10 11-50 51-100 101-200 201+ The top 50 operators accounted for 46% of the world’s pay TV subscribers by end- 2019. However, the top 10 will lose subscribers over the next five years, with the next 40 operators flat. Operators beyond these positions will gain subscribers. Simon Murray, Principal Analyst at Digital TV Research, said: “By end-2019, 13 operators had more than 10 million paying subscribers. This will reach 14 operators by 2025.” Eight operators will add more than 1 million subscribers between 2019 and 2025. China Unicom will win the most subs (19.96 million), followed by China Telecom (18.52 million). Eight operators will lose 1 million or more subscribers between 2019 and 2025, led by China Radio and TV with a 37 million loss. The next five losers will all be from the US. The Global Pay TV Operator Forecasts report covers 502 operators with 732 platforms [134 digital cable, 118 analog cable, 283 satellite, 140 IPTV and 57 DTT] across 135 countries. Global Pay TV Operator Forecasts Table of Contents Published in June 2020, this 302-page electronically-delivered report comes in two parts: • A 73-page PDF giving a global executive summary and forecasts. -

Firmware Updates

FIRMWARE UPDATES Issue 20 December 2017 BE THE FIRST TO UPDATE YOUR PHONE! Every week a new list and design. GALAXY A GALAXY ALPHA GALAXY C GALAXY J GALAXY FOLDER GALAXY NOTE GALAXY S5 GALAXY S6 GALAXY S7 GALAXY S8 GALAXY TAB GALAXY XCOVER SAMSUNG GALAXY A SERIES Model Name Country (Product Code) Model Version PDA GALAXY A3 Greece (Vodafone)(VGR) SM-A300FU 6.0.1 A300FUXXU1CQG3 GALAXY A3 Greece (Vodafone)(VGR) SM-A300FU 6.0.1 A300FUXXU1CQJ1 GALAXY A3 Netherlands (Vodafone) SM-A300FU 6.0.1 A300FUXXU1CQG3 (VDF) GALAXY A3 Netherlands (Vodafone) SM-A300FU 6.0.1 A300FUXXU1CQJ1 (VDF) GALAXY A3 Portugal (Vodafone) SM-A300FU 6.0.1 A300FUXXU1CQJ1 (TCL) GALAXY A5 Croatia (VIPNET)(VIP) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQJ2 GALAXY A5 Croatia (VIPNET)(VIP) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQF4 GALAXY A5 Czech Republic (Voda- SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQF4 fone)(VDC) GALAXY A5 Czech Republic (Voda- SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQJ2 fone)(VDC) GALAXY A5 Netherlands (Vodafone) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQF4 (VDF) GALAXY A5 Netherlands (Vodafone) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQJ2 (VDF) GALAXY A5 Portugal (Vodafone) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQJ2 (TCL) GALAXY A5 Portugal (Vodafone) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQF4 (TCL) GALAXY A5 Romania (Vodafone) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQJ2 (CNX) GALAXY A5 Romania (Vodafone) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQF4 (CNX) GALAXY A5 Switzerland (Swisscom) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQF4 (SWC) GALAXY A5 Switzerland (Swisscom) SM-A500FU 6.0.1 A500FUXXU1CQJ2 (SWC) Galaxy A3 Colombia(COO) SM-A320Y 7 A320YDXU1BQH2 Galaxy A3 Colombia(COO) SM-A320Y 7 A320YDXU1BQJ2 -

Badwpad: the Lasting Menace of a Bad Protocol

badWPAD: The Lasting Menace of a Bad Protocol Max Goncharov Trend Micro Forward-Looking Threat Research (FTR) Team A TrendLabsSM Research Paper TREND MICRO LEGAL DISCLAIMER The information provided herein is for general information Contents and educational purposes only. It is not intended and should not be construed to constitute legal advice. The information contained herein may not be applicable to all situations and may not reflect the most current situation. Nothing contained herein should be relied on or acted upon without the benefit of legal advice based on the 4 particular facts and circumstances presented and nothing herein should be construed otherwise. Trend Micro What is WPAD? reserves the right to modify the contents of this document at any time without prior notice. Translations of any material into other languages are intended solely as a convenience. Translation accuracy is not guaranteed nor implied. If any questions arise related to the accuracy of a translation, please refer to 8 the original language official version of the document. Any discrepancies or differences created in the translation are badWPAD Attacks not binding and have no legal effect for compliance or enforcement purposes. Although Trend Micro uses reasonable efforts to include accurate and up-to-date information herein, Trend Micro makes no warranties or representations of any kind as to its accuracy, currency, or completeness. You agree 13 that access to and use of and reliance on this document and the content thereof is at your own risk. Trend Micro Our WPAD Experiment disclaims all warranties of any kind, express or implied. Neither Trend Micro nor any party involved in creating, producing, or delivering this document shall be liable for any consequence, loss, or damage, including direct, indirect, special, consequential, loss of business profits, or special damages, whatsoever arising out of access to, use of, or inability to use, or in connection with the use of 21 this document, or any errors or omissions in the content thereof. -

Afstemmen Op Een Radiozender

Details over AM/FM-ontvangst Afstemmen op een radiozender Automatisch tunen 1. Druk enkele keren op TUNER op de afstandsbediening om "AM" of "FM" te selecteren. 2. Druk op TUN MODE zodat het "AUTO"controlelampje op het display gaat branden. 3. Druk op de cursors / om het automatisch tunen te starten. Als alternatief kunt u op TUNING op het hoofdtoestel drukken om het automatisch tunen te starten. Automatisch zoeken stopt wanneer een zender is gevonden. Wanneer op een radiozender ingetuned is, brandt het controlelampje " TUNED " op het display. Wanneer afgestemd op een FMradiozender zal de "FM STEREO"indicator branden. Er wordt geen geluid uitgevoerd terwijl de " TUNED "indicator uit is. Wanneer het signaal van een FMradiozender zwak is: Radiogolven kunnen zwak zijn afhankelijk van de bouwconstructie en omgevingsomstandigheden. In dat geval voert u de procedure uit zoals hieronder in "Handmatig Tunen" uitgelegd wordt, om de gewenste zender met de hand te selecteren. Handmatig tunen 1. Druk enkele keren op TUNER op de afstandsbediening om "AM" of "FM" te selecteren. 2. Druk op TUN MODE zodat het "AUTO"controlelampje op het display uitgaat. 3. Terwijl u op de cursors / drukt, selecteert u de gewenste radiozender. Als alternatief kunt u op TUNING op het hoofdtoestel drukken. De frequentie verandert met 1 stap iedere keer wanneer u op de knop drukt. De frequentie verandert voortdurend als de knop wordt ingedrukt en stopt wanneer de knop wordt losgelaten. Stem af door op het display te kijken. Naar automatisch tunen terugkeren: Druk nogmaals op TUN MODE op de afstandsbediening. Het toestel stemt automatisch af op een radiozender. -

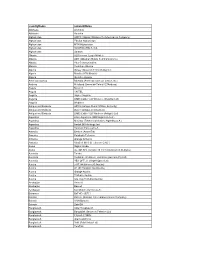

Cellcore Worldwide Coverage

countryName networkName Abkhazia A-Mobile Abkhazia Aquafon Afghanistan AWCC (Afghan Wireless Communication Company) Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan Afghanistan MTN Afghanistan Afghanistan ROSHAN (TDCA Ltd) Afghanistan Salaam Albania ALBtelecom (Eagle Mobile) Albania AMC (Albanian Mobile Communications) Albania Plus Communication Albania Vodafone Albania Algeria Djezzy (Orascom Telecom Algerie) Algeria Mobilis (ATM Mobilis) Algeria Ooredoo Algeria American Samoa BlueSky (American Samoa License, Inc.) Andorra Mobiland (Servei de Tele d%27Andorra) Angola Movicel Angola UNITEL Anguilla Digicel Anguilla Anguilla LIME (Cable %26 Wireless (Anguilla) Ltd) Anguilla Weblinks Antigua and Barbuda APUA (Antigua Public Utilities Authority) Antigua and Barbuda Digicel Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda LIME (Cable %26 Wireless (Antigua) Ltd) Argentina Claro Argentina (AMX Argentina S.A.) Argentina Movistar (Telefonica Moviles Argentina S.A.) Argentina Nextel (NII Holdings Inc) Argentina Telecom Personal S.A. Armenia Beeline (ArmenTel) Armenia Karabakh Telecom Armenia Orange Armenia Armenia VivaCell-MTS (K Telecom CJSC) Aruba Digicel Aruba Aruba SETAR N.V. (Servicio di Telecomunicacion di Aruba) Australia Telstra Australia Vodafone (Vodafone Hutchison Australia Pty Ltd) Australia YES OPTUS (Singtel Optus Ltd) Austria 3 AT (Hutchison 3G Austria) Austria A1 (A1 Telekom Austria AG) Austria Orange Austria Austria T-Mobile Austria Austria tele.ring (T-Mobile Austria) Azerbaijan Azercell Azerbaijan Bakcell Azerbaijan Nar Mobile (Azerfon LLC) Bahamas BaTelCo -

Elenco Paesi E Operatori Disponibili

Elenco Paesi e Operatori disponibili Country Operator Afghanistan Afghan Wireless Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan MTN Afghanistan Roshan Afghanistan Salaam Albania Vodafone Algeria Djezzy Algeria Mobilis Algeria Ooredoo Argentina Claro Argentina Movistar Argentina Nextel Argentina Personal Bangladesh Airtel Bangladesh Banglalink Bangladesh CityCell Bangladesh GrameenPhone Bangladesh Robi Bangladesh Teletalk Bolivia Entel Bolivia Tigo Bolivia Viva Brazil Algar Telecom Brazil Claro Brazil Movistar Brazil Nextel Brazil OI Brazil TIM Brazil Vivo Cameroon MTN Cameroon Orange Cape Verde CV Movel Cape Verde Unitel T+ Central African Republic Orange Chile Claro Chile Entel Chile Falabella Chile Movistar Chile Telsur Chile VTR Chile Virgin Mobile Chile Wom China Mobile China China Mobile China China Mobile China China Telecom China China Unicom China Colombia Avantel Colombia Claro Colombia Etb Colombia Movistar Colombia Tigo Colombia Uff Movil Colombia Une Colombia Virgin Mobile Costa Rica Claro Cuba Cel Cuba Democratic Republic of the Congo MTN Democratic Republic of the Congo Orange DRC Democratic Republic of the Congo Tatem DRCongo Dominican Republic Altice DR Dominican Republic Claro DR Dominican Republic Moun DR Dominican Republic Tricom DR Dominican Republic Viva DR Ecuador CNT Ecuador Claro Ecuador Movistar Ecuador Tuenti Egypt Etisalat Egypt Orange Egypt Vodafone El Salvador Claro El Salvador Digicel El Salvador Movistar El Salvador Tigo Ethiopia Ethiotelecom France Bouygues France Lebara France Lyca France Orange PIN France SFR PIN -

Download/FAQ of CRS.Pdf

An Analysis of the Binding Constraints on Digital Financial Inclusion in India Using a Decision Tree Methodology Nandini Harihareswara and Howard Miller Abstract The past decade has seen significant innovation and growth in the volume and value of digital payments in India. However, we find that the associated gains have been heavily concentrated in favor of wealthier and urban customers and have had less impact on lower- income and rural populations. While some customers now have a far greater selection of quick, cheap, and convenient digital payments methods, as much as 65 percent of the population remains effectively excluded. Using a decision tree framework, we test a range of factors on the supply and demand sides that could be binding constraints on further digital finance penetration. We find that an unlevel playing field in favor of the (primarily state-owned) banking sector results in a lack of effective competition that could be inhibiting greater innovation and outreach in favor of lower-income and marginalized people. This unlevel playing field is potentially a function of institutional weakness combined with the nexus of control of the government and the banking sector, which is reinforced by the position of the National Center for Global Payments Corporation of India. This control may also be viewed by the government as Development necessary to protect economic stability in a very dynamic market. To the extent that 2055 L Street NW institutional deficiencies are the root cause of regulatory barriers to the entry of new Fifth Floor providers and the scope of digital financial services offered, they are a binding constraint on Washington DC 20036 advancing digital financial inclusion. -

Africa Asia & Pacific Eastern Europe Access Communications (ACL) 3G

Africa Asia & Pacific Eastern Europe Access Communications (ACL) 3G Investments (Australia) A-Mobile AccessKenya AAPT Aero2 (incl. Mobyland) Albanian Broadband Company AFcom Advanced Info Service (AIS) (ABCOM) Albanian Mobile Communications Africa Cellulaire (Africell) Aircel (AMC) Africaonline (Tanzania) Aktel (Fonex) Albtelecom Africell (Gambia) Altel Alfa Cable Africonnect Altimax Broadcasting Alternative Digital Network (ADN) Airtel Seychelles Applifone (Star-Cell) Amis (formerly Medinet) Asia Pacific Broadband Wireless Al Madar Telecomm Company (APBW) Aquafon GSM Armenian Datacom Company Algerie Telecom Asia Pacific Telecom (APT) (ADC) Algerie Telecom Mobile (Mobilis) AsiaBell (AERO) ArmenTel (Beeline) Association for Telecommunication Alink Telecom Congo ASTEL Services (Americom) Allterra Gridline Communications Ghana Limited Axiata (formerly TM International) Astelit (life:)) Altech Stream Rwanda Axiata Bangladesh (Robi) Aster Angola Telecom B-Mobile Atlant Telecom Anupam Global Soft Babilon-M Az.Starnet Arobase Telecom Babilon-T Azercell Atlantic Wireless Liberia (Libercell) Bakrie Telecom Azerfon (Nar Mobile) Bangladesh Telecommunications Atlas Communications Company Ltd (BTCL) AzEuroTel Bell Benin Communication (BBCOM) Banglalink GSM AzTelekom Bayantel Telecommunications Benin Telecom (Bayan) AzTrank Benson Informatics Limited Beeline Tajikistan (Tacom) B.net Croatia Botswana Telecommunications Corporation (BTC) Bell Telecommunications (BellTel) Bakcell Broadmax Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd (BSNL) BakTelekom BTC Mobile (beMobile) -

Defining the Relevant Market in Telecommunications 2014

COMPETITION COMMITTEE COMPETITION COMMITTEE Defining the Relevant Market DEFINING THE RELE in Telecommunications VANT MARK Review of Selected OECD Countries and Colombia ET IN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 2014 2014 Defining the Relevant Market in Telecommunications Review of Selected OECD Countries and Colombia 2014 ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 34 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD. OECD Publishing disseminates widely the results of the Organisation’s statistics gathering and research on economics, social and environmental issues, as well as the conventions, guidelines and standards agreed by its members. This work is issued under the responsibility of the Secretary- General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OECD member countries.