Child Neurology: a Case of PMM2-CDG (CDG 1A) Presenting with Unusual Eye Movements Rohini Coorg and Timothy E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report DDUV 2009

Research at the de Duve Institute and Brussels Branch of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research August 2009 de Duve Institute Introduction 5 Miikka Vikkula 12 Frédéric Lemaigre 20 Annabelle Decottignies and Charles de Smet 25 Emile Vanschaftingen 31 Françoise Bontemps 37 Jean-François Collet 42 Guido Bommer 47 Mark Rider 50 Fred Opperdoes 56 Pierre Courtoy 62 Etienne Marbaix 69 Jean-Baptiste Demoulin 75 Jean-Paul Coutelier 80 Thomas Michiels 84 Pierre Coulie 89 LICR Introduction 95 Benoît Van den Eynde 98 Pierre van der Bruggen 106 Nicolas Van Baren 114 Jean-Christophe Renauld 119 Stefan Constantinescu 125 The de Duve Institute 5 THE DE DUVE INSTITUTE: AN INTERNATIONAL BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE In 1974, when Christian de Duve founded the Institute of Cellular Pathology (ICP), now rena- med the de Duve Institute, he was acutely aware of the constrast between the enormous progress in biological sciences that had occurred in the 20 preceding years and the modesty of the medical advances that had followed. He therefore crea- ted a research institution based on the principle that basic research in biology would be pursued by the investigators with complete freedom, but that special attention would be paid to the exploi- tation of basic advances for medical progress. It was therefore highly appropriate for the Institute to be located on the campus of the Faculty of Emile Van Schaftingen Medicine of the University of Louvain (UCL). This campus is located in Brussels. The Univer- sity hospital (Clinique St Luc) is located within walking distance of the Institute. The main commitment of the members of the de Duve Institute is research. -

PMM2 Gene Phosphomannomutase 2

PMM2 gene phosphomannomutase 2 Normal Function The PMM2 gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2). This enzyme is involved in a process called glycosylation, which attaches groups of sugar molecules (oligosaccharides) to proteins. Oligosaccharides are made up of many small sugar molecules that are attached to one another in a long chain. Glycosylation modifies proteins so they can perform a wider variety of functions. In one of the early steps of glycosylation, the PMM2 enzyme converts a molecule called mannose-6-phosphate to mannose-1-phosphate. Subsequently, mannose-1-phosphate is converted into GDP-mannose, which can transfer its small sugar molecule called mannose to the growing oligosaccharide chain. Once the correct number of small sugar molecules are linked together to form the oligosaccharide, it can be attached to a protein. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes PMM2-congenital disorder of glycosylation More than 115 mutations in the PMM2 gene have been found to cause PMM2- congenital disorder of glycosylation (PMM2-CDG, also known as congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ia). This is a severe condition that is characterized by developmental delay, weak muscle tone (hypotonia), abnormal distribution of fat, and various other signs and symptoms. The mutations that cause PMM2-CDG change the structure of the PMM2 enzyme in different ways; however, all of the mutations appear to result in reduced enzyme activity. Decreased activity of the PMM2 enzyme leads to a shortage of GDP-mannose within cells. As a result, there is not enough activated mannose to form oligosaccharides. Glycosylation cannot proceed normally because incorrect oligosaccharides are produced. -

'Improvement of Dolichol-Linked Oligosaccharide Biosynthesis by The

IMPROVEMENT OF DOLICHOL-LINKED OLIGOSACCHARIDE BIOSYNTHESIS BY THE SQUALENE SYNTHASE INHIBITOR ZARAGOZIC ACID Micha A. Haeuptle1,3, Michael Welti1,3, Heinz Troxler2, Andreas J. Hülsmeier1, Timo Imbach1, and Thierry Hennet1 1Institute of Physiology, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland; 2Division of Clinical Chemistry and Biochemistry, Children Hospital Zurich, Switzerland 3These authors contributed equally Running head: Zaragozic acid improves N-glycosylation Address correspondence to: Thierry Hennet, Institute of Physiology, University of Zürich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zürich, Switzerland. Phone: +41-44-635-5080. Fax: +41-44-635-6814. E-mail: [email protected] The majority of Congenital Disorders of involved in biosynthesis of lipid-linked Glycosylation (CDG) are caused by defects of oligosaccharide (LLO) required for N- dolichol (Dol)-linked oligosaccharide assembly, glycosylation (2) or proteins involved in glycan which lead to under-occupancy of N- processing (3,4) or transport of N-glycoproteins (5) glycosylation sites. Most mutations encountered form the molecular basis of CDG. The majority of in CDG are hypomorphic, thus leaving residual CDG encompass disorders affecting the assembly activity to the affected biosynthetic enzymes. We of the LLO precursor dolichol-pyrophosphate (Dol- hypothesized that increased cellular levels of PP)-GlcNAc2Man9Glc3, which leads to under- Dol-linked substrates might compensate for the occupancy of N-glycosylation sites (6). The low biosynthetic activity and thereby improve stepwise biosynthesis of the LLO precursor begins the output of protein N-glycosylation in CDG. at the cytosolic side of the endoplasmic reticulum To this end, we have investigated the potential of (ER) membrane by transfer of GlcNAc-P to the squalene synthase inhibitor zaragozic acid to dolichol-P (Dol-P) and completes at the luminal redirect the flow of the poly-isoprene pathway side of the ER membrane. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

The Analysis of Variants in the General Population Reveals That PMM2 Is Extremely Tolerant to Missense Mutations and That Diagno

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article The Analysis of Variants in the General Population Reveals That PMM2 Is Extremely Tolerant to Missense Mutations and That Diagnosis of PMM2-CDG Can Benefit from the Identification of Modifiers Valentina Citro 1, Chiara Cimmaruta 1, Maria Monticelli 1, Guglielmo Riccio 1, Bruno Hay Mele 1,2, Maria Vittoria Cubellis 1,* ID and Giuseppina Andreotti 3 ID 1 Dipartimento di Biologia, Università Federico II, 80126 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (G.R.); [email protected] (B.H.M.) 2 Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie ed Agroalimentari, Università Federico II, 80055 Napoli, Italy 3 Istituto di Chimica Biomolecolare—CNR, 80078 Pozzuoli, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-081-679118; Fax: +39-081-679233 Received: 30 May 2018; Accepted: 26 July 2018; Published: 30 July 2018 Abstract: Type I disorders of glycosylation (CDG), the most frequent of which is phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2-CDG), are a group of diseases causing the incomplete N-glycosylation of proteins. PMM2-CDG is an autosomal recessive disease with a large phenotypic spectrum, and is associated with mutations in the PMM2 gene. The biochemical analysis of mutants does not allow a precise genotype–phenotype correlation for PMM2-CDG. PMM2 is very tolerant to missense and loss of function mutations, suggesting that a partial deficiency of activity might be beneficial under certain circumstances. The patient phenotype might be influenced by variants in other genes associated with the type I disorders of glycosylation in the general population. -

Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation Type Ia)

European Journal of Human Genetics (2000) 8, 367–371 © 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd All rights reserved 1018–4813/00 $15.00 y www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Lack of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for the most prevalent PMM2 mutation in CDG-Ia (congenital disorders of glycosylation type Ia) Els Schollen1, Susanne Kjaergaard2, Eric Legius1, Marianne Schwartz2 and Gert Matthijs1 1Center for Human Genetics, University of Leuven, Belgium; 2Department of Clinical Genetics, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark The R141H mutation in the PMM2 gene is the most frequent mutation in type Ia of the congenital disorders of glycosylation (formerly carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndromes)(CDG-Ia). However, it has never been observed in the homozygous state. Homozygosity for this mutation is probably incompatible with life. In this study, we determined the frequency of R141H in two normal populations: in neonates of Dutch origin 1/79 were carriers, whilst in the Danish population, a carrier frequency of 1/60 was found. These figures are clearly in disequilibrium with the frequency of CDG-Ia that has been estimated at 1/80 000 to 1/40 000 in these populations. Haplotype analysis of 43 patients with the R141H mutation of different geographic origins indicated that the R141H is an old mutation in the Caucasian population. Based on the new data, the disease frequency has been calculated at 1/20 000 in these populations. It is concluded that the disease is probably underdiagnosed. European Journal of Human Genetics (2000) 8, 367–371. Keywords: N-glycosylation; carrier frequency; heterozygote advantage; phosphomannomutase; foetal wastage; recessive mutation Introduction mutations that retain residual enzymatic activity are tol- Congenital disorders of glycosylation type Ia (CDG-Ia, for- erated in patients. -

Downloaded from the App Store and Nucleobase, Nucleotide and Nucleic Acid Metabolism 7 Google Play

Hoytema van Konijnenburg et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis (2021) 16:170 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01727-2 REVIEW Open Access Treatable inherited metabolic disorders causing intellectual disability: 2021 review and digital app Eva M. M. Hoytema van Konijnenburg1†, Saskia B. Wortmann2,3,4†, Marina J. Koelewijn2, Laura A. Tseng1,4, Roderick Houben6, Sylvia Stöckler‑Ipsiroglu5, Carlos R. Ferreira7 and Clara D. M. van Karnebeek1,2,4,8* Abstract Background: The Treatable ID App was created in 2012 as digital tool to improve early recognition and intervention for treatable inherited metabolic disorders (IMDs) presenting with global developmental delay and intellectual disabil‑ ity (collectively ‘treatable IDs’). Our aim is to update the 2012 review on treatable IDs and App to capture the advances made in the identifcation of new IMDs along with increased pathophysiological insights catalyzing therapeutic development and implementation. Methods: Two independent reviewers queried PubMed, OMIM and Orphanet databases to reassess all previously included disorders and therapies and to identify all reports on Treatable IDs published between 2012 and 2021. These were included if listed in the International Classifcation of IMDs (ICIMD) and presenting with ID as a major feature, and if published evidence for a therapeutic intervention improving ID primary and/or secondary outcomes is avail‑ able. Data on clinical symptoms, diagnostic testing, treatment strategies, efects on outcomes, and evidence levels were extracted and evaluated by the reviewers and external experts. The generated knowledge was translated into a diagnostic algorithm and updated version of the App with novel features. Results: Our review identifed 116 treatable IDs (139 genes), of which 44 newly identifed, belonging to 17 ICIMD categories. -

Pseudouridylation Defect Due to DKC1 and NOP10 Mutations Causes Nephrotic Syndrome with Cataracts, Hearing Impairment, and Enterocolitis

Pseudouridylation defect due to DKC1 and NOP10 mutations causes nephrotic syndrome with cataracts, hearing impairment, and enterocolitis Eszter Balogha,b,1, Jennifer C. Chandlerc,1, Máté Vargaa,d,1,2, Mona Tahounc,e,1, Dóra K. Menyhárdf,g, Gusztáv Schaya,h, Tomas Goncalvesi, Renáta Hamard, Regina Légrádia,b, Ákos Szekeresb, Olivier Gribouvalj, Robert Kletak,l, Horia Stanescuk,l, Detlef Bockenhauerk, Andrea Kertia,b, Hywel Williamsm, Veronica Kinslern, Wei-Li Dio, David Curtisp, Maria Kolatsi-Joannouc, Hafsa Hammidc, Anna Szocs} q, Kristóf Perczela,b, Erika Makar, Gergely Toldib, Florentina Savaa, Christelle Arrondelj, Magdolna Kardoss, Attila Finthas, Ahmed Hossaint, Felipe D’Arcou, Mario Kaliakatsosv, Jutta Koeglmeierw, William Mifsudx, Mariya Moosajeey, Ana Faroz, Eszter Jávorszkya,b, Gábor Rudasq, Marwa H. Saiede, Salah Marzouke, Kata Kelenb, Judit Götzeb, George Reuszb, Tivadar Tulassayb, François Dragont,aa, Géraldine Molletj, Susanne Motamenybb, Holger Thielebb,cc, Guillaume Dorvalj, Peter Nürnbergbb,cc, András Perczelf,g, Attila J. Szabób,dd, David A. Longc, Kazunori Tomitai,ee, Corinne Antignacj,ff, Aoife M. Watersc,3,2, and Kálmán Torya,b,3,2 aMTA-SE Lendület Nephrogenetic Laboratory, Semmelweis University, HU 1083 Budapest, Hungary; bFirst Department of Pediatrics, Semmelweis University, HU 1083 Budapest, Hungary; cDevelopmental Biology and Cancer Programme, University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, WC1N 1EH London, United Kingdom; dDepartment of Genetics, Eötvös Loránd University, HU 1117 Budapest, -

Diseases Catalogue

Diseases catalogue AA Disorders of amino acid metabolism OMIM Group of disorders affecting genes that codify proteins involved in the catabolism of amino acids or in the functional maintenance of the different coenzymes. AA Alkaptonuria: homogentisate dioxygenase deficiency 203500 AA Phenylketonuria: phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) 261600 AA Defects of tetrahydrobiopterine (BH 4) metabolism: AA 6-Piruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency (PTS) 261640 AA Dihydropteridine reductase deficiency (DHPR) 261630 AA Pterin-carbinolamine dehydratase 126090 AA GTP cyclohydrolase I deficiency (GCH1) (autosomal recessive) 233910 AA GTP cyclohydrolase I deficiency (GCH1) (autosomal dominant): Segawa syndrome 600225 AA Sepiapterin reductase deficiency (SPR) 182125 AA Defects of sulfur amino acid metabolism: AA N(5,10)-methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency (MTHFR) 236250 AA Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency (CBS) 236200 AA Methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency 250850 AA Methionine synthase deficiency (MTR, cblG) 250940 AA Methionine synthase reductase deficiency; (MTRR, CblE) 236270 AA Sulfite oxidase deficiency 272300 AA Molybdenum cofactor deficiency: combined deficiency of sulfite oxidase and xanthine oxidase 252150 AA S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency 180960 AA Cystathioninuria 219500 AA Hyperhomocysteinemia 603174 AA Defects of gamma-glutathione cycle: glutathione synthetase deficiency (5-oxo-prolinuria) 266130 AA Defects of histidine metabolism: Histidinemia 235800 AA Defects of lysine and -

Whole-Genome Comparison Between the Type Strain of Halobacterium Salinarum (DSM 3754T) and the Laboratory Strains R1 and NRC-1

Whole-genome comparison between the type strain of Halobacterium salinarum (DSM 3754T) and the laboratory strains R1 and NRC-1. Friedhelm Pfeiffer, Gerald Losensky, Anita Marchfelder, Bianca Habermann and Mike Dyall-Smith MicrobiologyOpen, 2019, accepted Note: This document contains Supplementary Tables for the above manuscript. The legends use some terms which are only defined in the context of that manuscript. Here is one paragraph from that manuscript which briefly describes the content of the tables. Correlation of protein-coding genes among Halobacterium salinarum strains 91-R6T, R1, and NRC-1. As an annotation principle, every gene encoding a protein on a matching genome segment in one strain must have a correlated gene in the other strain. The gene sets of the three strains have been correlated in detail (for details see Methods of the associated manuscript and Appendix A4 and A5). Proteins are classified as strain- specific only after validation by tBLASTn that they are not mere missing gene calls. Correlated proteins, encoded on the chromosome of strains 91- R6 and R1 are listed in Table S1 (1986 proteins). The corresponding proteins from strain NRC-1 are also listed. In addition, there are regions of very high similarity between the plasmids from strains 91-R6 and R1, there are plasmid encoded correlated proteins, which are listed in Table S2. Furthermore, Table S2 lists proteins which are encoded on a plasmid in strain R1 but in a strain-specific region of the chromosome from strain 91- R6. Chromosomally encoded proteins from strain-specific regions of 91-R6 are listed in Table S3. -

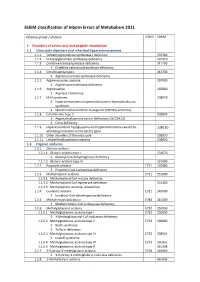

SSIEM Classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011

SSIEM classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011 Disease group / disease ICD10 OMIM 1. Disorders of amino acid and peptide metabolism 1.1. Urea cycle disorders and inherited hyperammonaemias 1.1.1. Carbamoylphosphate synthetase I deficiency 237300 1.1.2. N-Acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency 237310 1.1.3. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency 311250 S Ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency 1.1.4. Citrullinaemia type1 215700 S Argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency 1.1.5. Argininosuccinic aciduria 207900 S Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency 1.1.6. Argininaemia 207800 S Arginase I deficiency 1.1.7. HHH syndrome 238970 S Hyperammonaemia-hyperornithinaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome S Mitochondrial ornithine transporter (ORNT1) deficiency 1.1.8. Citrullinemia Type 2 603859 S Aspartate glutamate carrier deficiency ( SLC25A13) S Citrin deficiency 1.1.9. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia and hyperammonemia caused by 138130 activating mutations in the GLUD1 gene 1.1.10. Other disorders of the urea cycle 238970 1.1.11. Unspecified hyperammonaemia 238970 1.2. Organic acidurias 1.2.1. Glutaric aciduria 1.2.1.1. Glutaric aciduria type I 231670 S Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.1.2. Glutaric aciduria type III 231690 1.2.2. Propionic aciduria E711 232000 S Propionyl-CoA-Carboxylase deficiency 1.2.3. Methylmalonic aciduria E711 251000 1.2.3.1. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency 1.2.3.2. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase deficiency 251120 1.2.3.3. Methylmalonic aciduria, unspecified 1.2.4. Isovaleric aciduria E711 243500 S Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.5. Methylcrotonylglycinuria E744 210200 S Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency 1.2.6. Methylglutaconic aciduria E712 250950 1.2.6.1. Methylglutaconic aciduria type I E712 250950 S 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency 1.2.6.2. -

Characterisation of the Potential of Probiotics Or Their Extracts As Therapy for Skin

Characterisation of the potential of probiotics or their extracts as therapy for skin A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences 2014 Walaa Mohammedsaeed, Master of Science (MSc) School of Medicine Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................. 2 Table of Figures ................................................................................................................ 5 List of Tables .................................................................................................................... 8 List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................ 9 1 Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 11 2 Declaration .................................................................................................................. 12 3 Copyright Statement .................................................................................................... 13 4 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... 14 5 The author ................................................................................................................... 15 6 Publications arising from this Thesis ...........................................................................