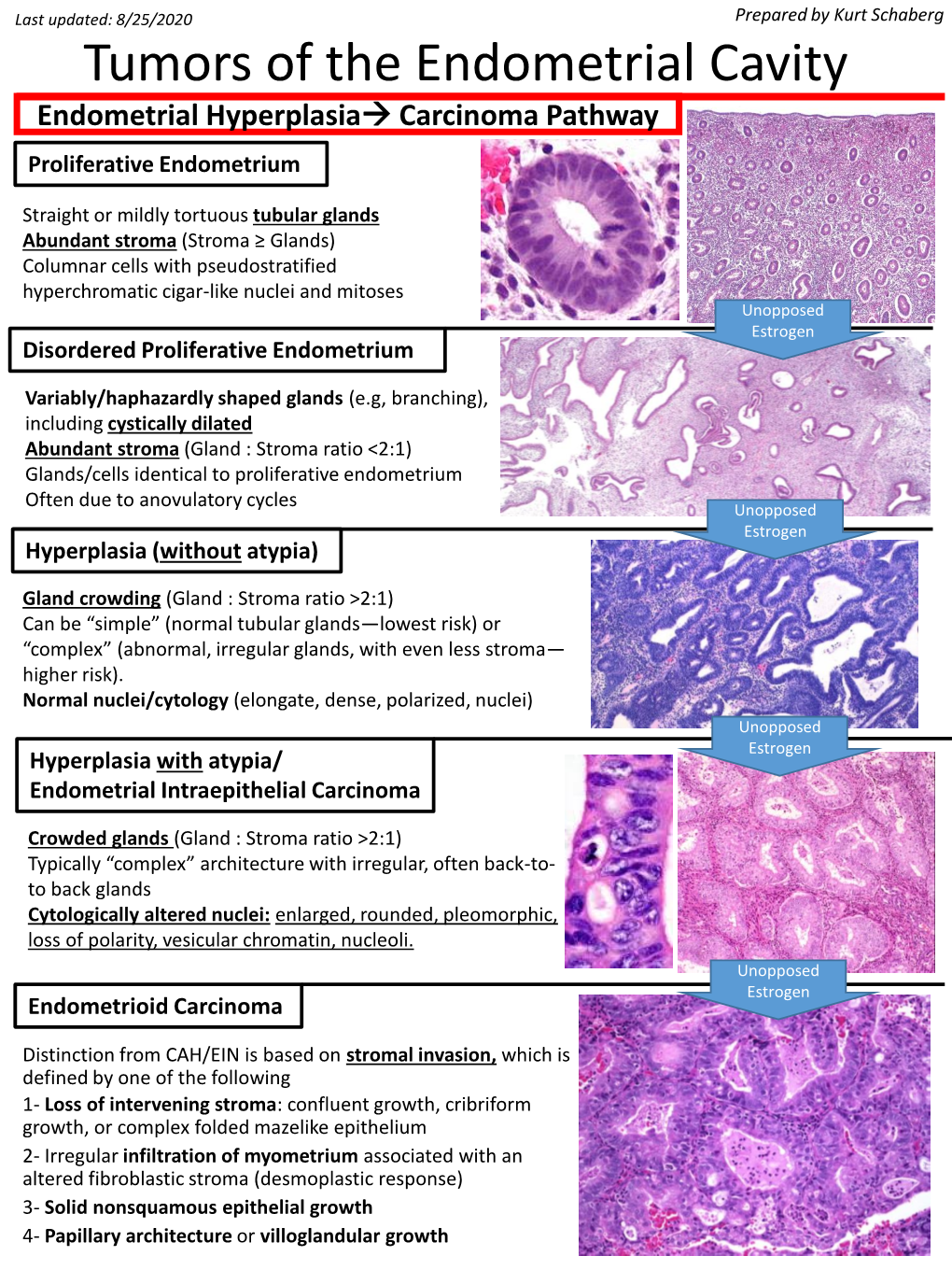

Tumors of the Endometrial Cavity Endometrial Hyperplasia→ Carcinoma Pathway Proliferative Endometrium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aderomyoma of the Common Bile Duct --Report of a Case

Yamanashl Med. J. 4 (2), 83"v87, 1989 Case Report AdeRomyoma of the Common Bile Duct --Report of a Case Yoshiro MATsuMoTe, Masatoshi MoGAKi, Hidehisa AoyAMA, Takayoshi SEKmAwA, Katsnhiko SuGAHARA, Koichi SuDAi), and Masayuki FuJiNo2) DePa,rt・ment of Surge7pu. i)DePartment of Pathology, 2)DePartment of lnte7"nal Medicine, YamanasJzi Medical Coglege, Tamaho, Nakakoma, Ya?nanashi 409-38, JaPan Abstract: Adenomyomas in the extrahepatic biie duc£ are extremely rare. In a 75-year- old male with acute cholangitis due to adenomyoma £erming a protruding lesion iR the terminal bile duct, pamacreatoduodenectomy was carried out, resulting complete cure, Key words: Adenomyoma of the common bile duct, Early bile dact cancer, Obstructive jaundice formed, aRd £rom the histologic examina- INTRODUCTION tion of the surgical specimen, adenomyoma Adenomyoma in the biliary ductal system of the common bile duct was confirmed. is most freguently fouRd in the gallbladder. Although beRign neoplasma o£ the bile The gallbiadder wall is more abuRdant in duct system are uncommon, the tumors are muscle fibers than is the wall o£ the bile clinically very important because they can duct. Adenomyoma in the gallbladder is cause obstructive jaundice4) and require knowlt to be closely re}ated to the forma- differentiation £rom eary cancer of the bile tion of gallstones. In other parts of the duct. biliary ductal system, kex4xeve]-, adeno- We report here the surgical results and myoma is very rarei)・2), although a few pathologic findings in a case of adeno- cases of a tumor arising from the papil}a myoma of the terminal bile duct. of Vater3) have beelt reported. -

HIV-1: Cancer Evaluation 8/1/16

Report on Carcinogens Monograph on Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 August 2016 Report on Carcinogens Monograph on Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 August 1, 2016 Office of the Report on Carcinogens Division of the National Toxicology Program National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences U.S. Department of Health and Human Services This Page Intentionally Left Blank RoC Monograph on HIV-1: Cancer Evaluation 8/1/16 Foreword The National Toxicology Program (NTP) is an interagency program within the Public Health Service (PHS) of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and is headquartered at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIEHS/NIH). Three agencies contribute resources to the program: NIEHS/NIH, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (NIOSH/CDC), and the National Center for Toxicological Research of the Food and Drug Administration (NCTR/FDA). Established in 1978, the NTP is charged with coordinating toxicological testing activities, strengthening the science base in toxicology, developing and validating improved testing methods, and providing information about potentially toxic substances to health regulatory and research agencies, scientific and medical communities, and the public. The Report on Carcinogens (RoC) is prepared in response to Section 301 of the Public Health Service Act as amended. The RoC contains a list of identified substances (i) that either are known to be human carcinogens or are reasonably anticipated to be human carcinogens and (ii) to which a significant number of persons residing in the United States are exposed. The NTP, with assistance from other Federal health and regulatory agencies and nongovernmental institutions, prepares the report for the Secretary, Department of HHS. -

SNOMED CT Codes for Gynaecological Neoplasms

SNOMED CT codes for gynaecological neoplasms Authors: Brian Rous1 and Naveena Singh2 1Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust and 2Barts Health NHS Trusts Background (summarised from NHS Digital): • SNOMED CT is a structured clinical vocabulary for use in an electronic health record. It forms an integral part of the electronic care record, and serves to represent care information in a clear, consistent, and comprehensive manner. • The move to a single terminology, SNOMED CT, for the direct management of care of an individual, across all care settings in England, is recommended by the National Information Board (NIB), in “Personalised Health and Care 2020: A Framework for Action”. • SNOMED CT is owned, managed and licensed by SNOMED International. NHS Digital is the UK Member's National Release Centre for the creation of, and delegated authority to licence the SNOMED CT Edition and derivatives. • The benefits of using SNOMED CT in electronic care records are that it: • enables sharing of vital information consistently within and across health and care settings • allows comprehensive coverage and greater depth of details and content for all clinical specialities and professionals • includes diagnosis and procedures, symptoms, family history, allergies, assessment tools, observations, devices • supports clinical decision making • facilitates analysis to support clinical audit and research • reduces risk of misinterpretations of the record in different care settings • Implementation plans for England: • SNOMED CT must be implemented across primary care and deployed to GP practices in a phased approach from April 2018. • Secondary care, acute care, mental health, community systems, dentistry and other systems used in direct patient care must use SNOMED CT as the clinical terminology, before 1 April 2020. -

Polypoid Adenomyoma of the Uterus

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.4044 Polypoid Adenomyoma of the Uterus Nida Sajjad 1 , Hina Iqbal 1 , Kumail Khandwala 1 , Shaista Afzal 1 1. Radiology, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, PAK Corresponding author: Kumail Khandwala, [email protected] Abstract Polypoid adenomyoma is a rare uterine endometrial polypoid tumor of mixed epithelial and mesenchymal origin. Although the clinical and pathologic features of polypoid adenomyomas have been described extensively, imaging findings for these tumors have not been frequently reported in the literature. On imaging, their features may be confused with prolapsed leiomyomas or malignancy. Hemorrhagic cystic spaces in a prolapsed uterine tumor within the vagina should raise consideration of a diagnosis of polypoid adenomyoma. Such blood-containing cystic spaces would be unusual findings in leiomyomas and malignancy. Diagnosing polypoid adenomyoma is vital because it can potentially be managed by hysteroscopic resection, unlike an ordinary form of adenomyosis. Categories: Obstetrics/Gynecology, Radiology Keywords: mesenchymal tumor, atypical polypoid adenomyoma, uterus Introduction Polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus is an endometrial polyp in which the stromal component is made up of smooth muscle [1]. These are benign tumors and account for 1.3% of all endometrial polyps. Polypoid adenomyomas are of mixed epithelial and mesenchymal origin [2]. Although their clinical and pathological features have been described well in literature, imaging findings for these tumors have been seldom reported. We report a case of a 44-year-old woman with urinary retention who had a prolapsed polypoidal uterine lesion on imaging which was confirmed to be polypoid adenomyoma on histopathology. We aim to review the imaging findings and the relevant literature on this rare entity. -

Sonography of Adenomyosis

3105jumonline.qxp:Layout 1 4/19/12 9:48 AM Page 805 SOUND JUDGMENT SERIES Sonography of Adenomyosis Khaled Sakhel, MD, Alfred Abuhamad, MD Invited paper denomyosis was first described by Rokitansky in 1860 as “cystosarcoma adenoides uterinum” and was later defined A by Von Recklinghausen in 1896. It is a common condition that predominantly affects women in the late reproductive years. Adenomyosis has been noted to occur in about 30% of the general female population and in up to 70% of hysterectomy specimens depending on the definition of the entity.1 The diagnosis can be The Sound Judgment Series consists of made with sonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but invited articles highlighting the clinical this article will show that sonography should be the imaging modal- value of using ultrasound first in specific ity of choice for adenomyosis. clinical diagnoses where ultrasound has Definition shown comparative or superior value. The series is meant to serve as an educational Adenomyosis is defined by the presence of ectopic endometrial tool for medical and sonography students glands and stroma within the myometrium. The presence of ectopic and clinical practitioners and may help endometrial glands and stroma induces a hypertrophic and hyper- integrate ultrasound into clinical practice. plastic reaction in the surrounding myometrial tissue. Clinical Presentation Most patients with adenomyosis are asymptomatic. Symptoms related to adenomyosis include dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and menstrual menometrorrhagia. Adeno- myosis presents most commonly as a diffuse disease involving the entire myometrium (Figure 1). It can also present in a focal area of the uterus, known as adenomyoma (Figure 2). -

Conversion of Morphology of ICD-O-2 to ICD-O-3

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH National Cancer Institute to Neoplasms CONVERSION of NEOPLASMS BY TOPOGRAPHY AND MORPHOLOGY from the INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES FOR ONCOLOGY, SECOND EDITION to INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES FOR ONCOLOGY, THIRD EDITION Edited by: Constance Percy, April Fritz and Lynn Ries Cancer Statistics Branch, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program National Cancer Institute Effective for cases diagnosed on or after January 1, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................... 1 Morphology Table ..................................... 7 INTRODUCTION The International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition1 (ICD-O-3) was published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2000 and is to be used for coding neoplasms diagnosed on or after January 1, 2001 in the United States. This is a complete revision of the Second Edition of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology2 (ICD-O-2), which was used between 1992 and 2000. The topography section is based on the Neoplasm chapter of the current revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Tenth Revision, just as the ICD-O-2 topography was. There is no change in this Topography section. The morphology section of ICD-O-3 has been updated to include contemporary terminology. For example, the non-Hodgkin lymphoma section is now based on the World Health Organization Classification of Hematopoietic Neoplasms3. In the process of revising the morphology section, a Field Trial version was published and tested in both the United States and Europe. Epidemiologists, statisticians, and oncologists, as well as cancer registrars, are interested in studying trends in both incidence and mortality. -

Atypical Stromal Cells As a Diagnostic Pitfall in Lesions of the Lower Female Genital Tract and Uterus: a Review and Presentation of Some Unusual Cases

Patología 2009;47(2):103-7 Revista latinoamericana 2ULJLQDODUWLFOH Atypical stromal cells as a diagnostic pitfall in lesions of the lower female genital tract and uterus: a review and presentation of some unusual cases MI Rodrigues,* E Goez,** K Larios K,*** M Cuevas,**** J Aneiros Fernandez,**** S Stolnicu,1 FF Nogales**** RESUMEN Antecedentes: las células estromales atípicas (CEAts) en el conducto genital femenino son un hallazgo poco frecuente en lesiones polipoides de vulva, vagina, cuello uterino y endometrio, lo que con frecuencia genera errores diagnósticos. Objetivo: mostrar los hallazgos de 12 casos enviados a consulta por la sospecha de una lesión maligna. Material y métodos: estudio clínico-patológico de 12 casos con inmunohistoquímica de actina, desmina, S100, Ki67, RE y RP. Resultados: las células estromales atípicas se encontraron en un patrón multifocal, en tres casos de lesiones de vulva (incluido un caso de liquen escleroso), dos pólipos vaginales, dos casos de cuello uterino, incluido uno prolapsado y un carcinoma escamoso y, por último, cuatro casos de pólipos endometriales y un caso de adenomiosis. Los marcadores de inmunohistoquímica en las células estromales atí- picas fueron positivos para receptores hormonales de estrógenos y progesterona y sólo focalmente para actina. El índice de proliferación Ki67 fue bajo. ConclusionesODVFpOXODVHVWURPDOHVDWtSLFDVVRQUHDFWLYDVQRHVSHFt¿FDVRGHJHQHUDWLYDVFRQXQtQGLFHGHSUROLIHUDFLyQPX\EDMRFRQ receptores hormonales y capacidad para expresar marcadores de músculo liso y de estroma endometrial. Presentamos casos, hasta ahora no publicados, de células estromales atípicas asociadas a un liquen escleroso en la vulva, un carcinoma escamoso del cuello uterino y un cuello uterino prolapsado. Se plantean además, como diagnósticos diferenciales, sitio de implantación exagerado y nevo azul, ya que las células trofoblásticas y névicas presentan características similares a las células estromales atípicas. -

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making Biomed Central

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making BioMed Central Software Open Access Automatic extraction of candidate nomenclature terms using the doublet method Jules J Berman* Address: Cancer Diagnosis Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA Email: Jules J Berman* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 18 October 2005 Received: 07 January 2005 Accepted: 18 October 2005 BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2005, 5:35 doi:10.1186/1472-6947-5-35 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/5/35 © 2005 Berman; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: New terminology continuously enters the biomedical literature. How can curators identify new terms that can be added to existing nomenclatures? The most direct method, and one that has served well, involves reading the current literature. The scholarly curator adds new terms as they are encountered. Present-day scholars are severely challenged by the enormous volume of biomedical literature. Curators of medical nomenclatures need computational assistance if they hope to keep their terminologies current. The purpose of this paper is to describe a method of rapidly extracting new, candidate terms from huge volumes of biomedical text. The resulting lists of terms can be quickly reviewed by curators and added to nomenclatures, if appropriate. The candidate term extractor uses a variation of the previously described doublet coding method. -

Adenomyoma of Endocervical Type of The

Hauptmann et al. Obstet Gynecol cases Rev 2015, 2:6 ISSN: 2377-9004 Obstetrics and Gynaecology Cases - Reviews Case Report: Open Access Adenomyoma of Endocervical Type of the Cervix Uteri with Reactive Atypia and Goblet Cell Differentiation – A Case Report and Review of the Literature Steffen Hauptmann1*, Katja Mohr2 and Regina Grosse2 1Medical Service Center for Gynecology, Cytology, and Histology, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany 2Department of Gynecology, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany *Corresponding author: Steffen Hauptmann, MD., Medical Service Center for Gynecology, Cytology, and Histology, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Eisenbahnstr, 50-52, D-66424 Homburg (Saar), Germany, Tel: +49- 6841-993252, Fax: +49-6841-993253, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Case Report In this report we present the rare case of a 53 years old woman A 53 years old postmenopausal female presented with a feeling with an adenomyoma of endocervical type of the cervix uteri with of pressure and heaviness in the bladder region as well as abnormal reactive atypia and focal goblet cell differentiation. The epithelium vaginal bleeding. During hysteroscopy a slight enlargement of the of the lesion was MUC5AC positive, making this marker invalid in anterior part of the cervix was noticed. Curettage revealed only excluding the most important differential diagnosis of this lesion, the immature squamous metaplasia of the endocervical epithelium minimal deviation adenocarcinoma. The most relevant literature is reviewed and the differential diagnoses are discussed. Introduction Cullen firstly described Adenomyomas in 1896 [1]. They are much more common in the corpus than in the cervix uteri and belong to the group of mixed Mullerian tumors of the female genital tract. -

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Tumours

S3.02 The tumour type(s) must be recorded. CS3.02a The WHO classification is recommended.2 Refer to Appendix 4. Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Tumours Epithelial tumours Squamous and related tumours and precursors Squamous cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified 8070/3 Keratinizing 8071/3 Non- keratinizing 8072/3 Basaloid 8083/3 Warty 8051/3 Verrucous 8051/3 Keratoacanthoma-like Variant with tumour giant cells Others Basal cell carcinoma 8090/3 Squamous intraepithelial neoplasia Vulva intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) 8077/2 Squamous cell carcinoma in situ 8070/2 Benign squamous lesions Condyloma acuminatum Vestibular papilloma (micropapillomatosis) 8052/0 Fibroepithelial polyp Seborrheic and inverted follicular keratosis Keratoacanthoma Glandular tumours Paget disease 8542/3 Bartholin gland tumours Adenocarcinoma 8140/3 Squamous cell carcinoma 8070/3 Adenoid cystic carcinoma 8200/3 Adenosquamous carcinoma 8560/3 Transitional cell carcinoma 8120/3 Small cell carcinoma 8040/0 Adenoma 8140/0 Adenomyoma 8932/0 Others Tumours arising from specialised anogenital mammary-like glands Adenocarcinoma of mammary gland type 8500/3 Papillary hidradenoma 8405/0 Others Adenocarcinoma of Skene gland origin 8140/3 Adenocarcinomas of other types 8140/3 Adenoma of minor vestibular glands 8140/0 Mixed tumour of the vulva 8940/0 Tumours of skin appendage origin Malignant sweat gland tumours 8400/3 Sebaceous carcinoma 8410/3 Syringoma 8407/0 Nodular hidradenoma 8402/0 Trichoepithelioma 8100/0 Others Soft Tissue tumours Sarcoma botryoides 8910/3 Leiomyosarcoma -

Diagnosis and Management of Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma in a Woman with Prolapsing Cervical Mass Elizabeth V

Connor and Disilvestro. Obstet Gynecol cases Rev 2015, 2:4 ISSN: 2377-9004 Obstetrics and Gynaecology Cases - Reviews Case Report: Open Access Diagnosis and Management of Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma in a Woman with Prolapsing Cervical Mass Elizabeth V. Connor1* and Paul A. Disilvestro2 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, USA 2Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, USA *Corresponding author: Elizabeth V. Connor, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, 101 Dudley Street, Providence, RI 02905, USA, Tel: 401-274-1122, E-mail: [email protected] [4]. Due to the rarity of rhabdomyosarcoma in older women, firm Abstract management guidelines are non-existent. Additionally, prognostic Background: Cervical rhabdomyosarcoma is very rare, comprising information for patients is lacking. We present the case of a woman in less than 1% of cervical cancers in adult women. Less than 40 her thirties diagnosed with cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. cases of cervical rhabdomyosarcoma have been reported in adult women in the last 50 years. Due to the rarity of this disease, Case Report management guidelines are non-existent. A 35-year-old woman, gravida 2 para 2, presented to the Case: We present a 36-year-old woman who presented with pelvic emergency room with pelvic pain and a mass prolapsing from the pain and a vaginal mass. The mass was excised, and pathology confirmed poorly differentiated embryonal type rhabdomyosarcoma. vagina. She reported that the mass had grown within the preceding She then underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral two weeks. -

Table of Contents

CONTENTS 1. Embryology of the Lower Female Genital Tract ........................................................... 1 Cervix and Vagina ..................................................................................................... 1 Vulva .......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Anatomy of the Lower Female Genital Tract ............................................................... 7 Cervix ......................................................................................................................... 7 Gross Anatomy ....................................................................................................... 7 Lymphatic Drainage ............................................................................................... 7 Colposcopic Features and Microscopic Anatomy .................................................. 8 Squamous Epithelium ............................................................................................ 8 Endocervical Glandular Epithelium ....................................................................... 10 Transformation Zone .............................................................................................. 11 Vagina ........................................................................................................................ 16 Gross Anatomy ....................................................................................................... 16 Lymphatic Drainage