Figuration and Form in Hartmann's Concerto for Viola, Piano, Wind Instruments, and Percussion (1954-6)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

Pastiche for Piano on Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music

Pastiche For Piano On Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music Download pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2619 times and last read at 2021-09-28 10:12:03. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Method, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 sheet music has been read 3180 times. Opus calidoscopium in memory of sorabji op 2 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 19:02:59. [ Read More ] Pastiche 2017 Pastiche 2017 sheet music has been read 2663 times. Pastiche 2017 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 02:51:33. [ Read More ] Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 sheet music has been read 2729 times. Virtuoso etude no 4 in memory of sorabji nocturne op 1 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 05:00:02. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Conducting from the Piano: a Tradition Worth Reviving? a Study in Performance

CONDUCTING FROM THE PIANO: A TRADITION WORTH REVIVING? A STUDY IN PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: MOZART’S PIANO CONCERTO IN C MINOR, K. 491 Eldred Colonel Marshall IV, B.A., M.M., M.M, M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2018 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor David Itkin, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Marshall IV, Eldred Colonel. Conducting from the Piano: A Tradition Worth Reviving? A Study in Performance Practice: Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C minor, K. 491. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2018, 74 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. Is conducting from the piano "real conducting?" Does one need formal orchestral conducting training in order to conduct classical-era piano concertos from the piano? Do Mozart piano concertos need a conductor? These are all questions this paper attempts to answer. Copyright 2018 by Eldred Colonel Marshall IV ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: A BRIEF HISTORY OF CONDUCTING FROM THE KEYBOARD ............ 1 CHAPTER 2. WHAT IS “REAL CONDUCTING?” ................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 3. ARE CONDUCTORS NECESSARY IN MOZART PIANO CONCERTOS? ........................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271 “Jeunehomme” (1777) ............................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 13 in C major, K. 415 (1782) ............................................................. 23 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 (1785) ............................................................. 25 Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Quintet for Piano and Four Stringed Instruments and Its Intended Performance by Norah Drewett and the Hart House String Quartet

91 Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Quintet for Piano and Four Stringed Instruments and its intended performance by Norah Drewett and the Hart House String Quartet Marc-AndrC Roberge Abstract This article attempts to reconstruct the history of what was to be the first per- formance of Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Quintet for Piano and Four Stringed Instruments (1919-20), which was scheduled to be given on 29 November 1925 at Aeolian Hall in New York by the pianist Norah Drewett and the University of Toronto's Hart House String Quartet as part of a concert sponsored by Edgard Varese's International Composers' Guild. The performance never took place for reasons that are not entirely clear but have to do mostly with the work's difficul- ties. The article also provides an introduction to the work itself, which Sorabji dedicated to his friend, the composer Philip Heseltine. Most people who have heard of Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988), the Parsi composer and pianist active who lived as a recluse in England for most of his career, know that performances of his often massive and extremely difficult works have been extremely rare as a result of a so-called ban.l The thirteen scores that Sorabji published between 1921 and 1931 contain the following warning: "All rights including that of performance, reserved for all countries by the composer." The score of his 248-page Opus clavicembalisticum (1929-30), his longest and most often cited work, contains the additional admonition: "Public performance prohibited unless by express consent of the composer." Various statements in letters make it possible to say that, in the late thirties, Sorabji had decided to turn down all requests for public performance either by himself or by others. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart – Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Mozart entered this concerto in his catalog on February 10, 1785, and performed the solo in the premiere the next day in Vienna. The orchestra consists of one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At these concerts, Shai Wosner plays Beethoven’s cadenza in the first movement and his own cadenza in the finale. Performance time is approximately thirty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20 were given at Orchestra Hall on January 14 and 15, 1916, with Ossip Gabrilowitsch as soloist and Frederick Stock conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 15, 16, and 17, 2007, with Mitsuko Uchida conducting from the keyboard. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 6, 1961, with John Browning as soloist and Josef Krips conducting, and most recently on July 8, 2007, with Jonathan Biss as soloist and James Conlon conducting. This is the Mozart piano concerto that Beethoven admired above all others. It’s the only one he played in public (and the only one for which he wrote cadenzas). Throughout the nineteenth century, it was the sole concerto by Mozart that was regularly performed—its demonic power and dark beauty spoke to musicians who had been raised on Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt. -

Joseph-Haas-Info

Vielen Dank an Wolfgang Haas, der uns diese Biographie zukommen ließ. Joseph Haas Joseph Haas wurde am 19. März 1879 in Maihingen im schwäbischen Ries als 3. Kind des dortigen Lehrers geboren. Schon früh zeigte sich seine musikalische Begabung. Zunächst wurde er aber Lehrer. Nach erfolgreicher Prüfung versuchte er seine musikalischen Studien zu vervollkommnen. Entscheidend war dabei die Begegnung mit Max Reger, dem er bis Leipzig folgte. Schon bald zeigten sich die ersten Erfolge als Komponist, die ihm 1911 die Berufung als Lehrer für Komposition am Konservatorium in Stuttgart und 1921 die Berufung an die Akademie der Tonkunst in München brachten. Konsequent ging er in seinem Schaffen von der Kammermusik über Lieder und Chorwerke zu den großen Orchesterwerken, Oratorien und Opern. Von den bedeutenden Werken seien die beiden Opern "Tobias Wunderlich" und "Die Hochzeit des Jobs", die Oratorien "Die heilige Elisabeth", "Das Lebensbuch Gottes", "Das Jahr im Lied" und "Die Seligen", von den Liederzyklen "Gesänge an Gott" nach Gedichten von Jakob Kneip und "Unterwegs" nach Gedichten von Hermann Hesse, von den Messen die "Speyerer Domfestmesse" und die "Münchner Liebfrauenmesse" sowie von den Kammermusikwerken das Streichquartett A Dur op. 50, die Violinsonate h Moll op. 21 und die Klaviersonate a Moll op. 46 genannt. Im Jahre 1921 gründete Joseph Haas mit Paul Hindemith und Heinrich Burkard die "Donaueschinger internationalen Kammermusikfeste für Neue Musik" und bewies damit seine Aufgeschlossenheit für alles Neue, obwohl er selbst stets tonal komponierte. Schon bald war er einer der gesuchtesten Kompositionslehrer in Deutschland. Aus seiner Meisterklasse gingen so unterschiedliche Künstler hervor wie Karl Amadeus Hartmann, Karl Höller, Philipp Mohler, Cesar Bresgen oder die Dirigenten Eugen Jochum und Wolfgang Sawallisch. -

Student Achievements 2019 - 2020

Student Achievements 2019 - 2020 SUMMER 2020 8.20 Academy cellist Jan Vargas-Nedvetsky was named winner of the Chicago Chamber Music Festival 6th Annual Concerto Competition for pianists and string players. The winners will be invited to perform with the Northeastern Illinois University Orchestra conducted by Dr. Benjamin Firer during the ‘20 - ‘21 Academic Year. * CCMF Concerto Competition is open to pre-college students only. Perform with NEIU Orchestra during the ‘20 - ‘21 season. • Receive written feedback from a panel of three renowned orchestra conductors • ONE private lesson with CCMF’s faculty* • ONE private meeting with conductor for valuable insight into playing as a soloist with an orchestra • Access to CCMF Special Topic Seminars Pianist Clara Zhang was the winner of the 2018 Concerto Competition. 2020 Chicago International Music Competition 8.20 Congratulations to members of PRIMAVERA AND DASANI ensembles…. tying for the Grand Prize at the 2020 Chicago International Music Competition. More than 400 musicians in 22 countries applied to the virtual competition. GRAND PRIZES DIVISION II—Amateur Division 1st Prize—Trio Primavera coached by Rodolfo Vieira and Mark George. (US): Jan Vargas Nedvetsky / Esme Arias-Kim / Yerin Yang Tied with Dasani String Quartet coached by Mathias Tacke. (US): Isabella Brown/ Katya Moeller/ Zechariah Mo/ Brandon Cheng 2nd Prize—Not Awarded 3rd Prize—Brian Lin (US) In addition, the Academy had winners in the Professional Young Artist II Division. Isabella Brown was awarded first prize, and Katya Moeller second prize, in the Professional Young Artist II Division. Congratulations to everyone for high achievements in a distinguished competition. 7.1.20 - Träumerei Project: Timeless Tribute Video With no end of year orchestra concert, no last day to say goodbye, and no graduation ceremony for the seniors, the Academy Class of 2019-2020, in their homes across four states, created a Time Capsule Video to honor their year together. -

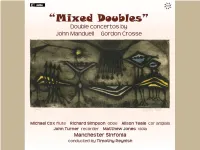

Gordon Crosse

“Mixed Doubles” Double Concertos by John Manduell and Gordon Crosse CD1: Music by Gordon Crosse (b. 1937) 1 Brief Encounter, for oboe d’amore, recorder and strings (2009) 10.09 Concerto for viola and strings with french horn (2009) 22.50 2 I. Prelude: Andante calmo –più mosso – vivace 8.18 3 II. Song: Lento semplice – più mosso – lento 7.08 4 III. Finale: Vivace 7.24 5 Fantasia on ‘Ca’ the Yowes’, for recorder, harp and strings (2009) 9.51 Total duration CD1 43.05 CD2: Music by John Manduell (b. 1928) Flutes Concerto, for flautist, harp, strings and percussion (2000) 26.56 1 I. Vivo – Lento 9.55 2 II. Quasi adagio 9.24 3 III. Allegro – Allegretto – Languido 7.37 Double Concerto, for oboe, cor anglais, strings and percussion (1985/2012) 28.14 4 I. Quasi adagio – allegro molto 10.43 5 II. Adagio molto 12.18 6 III. Allegro vivo 5.13 Total duration CD2 55.19 Michael Cox flute Richard Simpson oboe/oboe d’amore Alison Teale cor anglais John Turner recorder Matthew Jones viola Timothy Jackson french horn Anna Christensen harp (CD1 track 5) Deian Rowlands harp (CD2 tracks 1-3) MANCHESTER SINFONIA leader Richard Howarth conducted by Timothy Reynish The Music Gordon Crosse writes: All three pieces on CD1 were composed in the Summer and Autumn of 2009 which was the most exciting and productive year I have ever experienced. I had returned to composing after a break of some 18 years and I found I couldn't stop working. The music was simpler than it was in 1990 but I think more communicative because more concentrated and focused. -

Graduate Recital in Viola

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2017 Graduate recital in viola Isaak Walter Sund University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2017 Isaak Walter Sund Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Sund, Isaak Walter, "Graduate recital in viola" (2017). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 413. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/413 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRADUATE RECITAL IN VIOLA An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music in Performance Isaak Walter Sund University of Northern Iowa July 2017 This Study by: Isaak Sund Entitled: Graduate Recital in Viola has been approved as meeting the thesis requirement for the Degree of Master of Music in Performance ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Julia Bullard, Chair, Thesis Committee ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Rebecca Burkhardt, Thesis Committee Member ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Alison Altstatt, Thesis Committee Member ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Kavita R. Dhanwada, Dean, Graduate College This Recital Performance by: Isaak Sund Entitled: Graduate Recital in Viola Date of Recital: March 29, 2017 has been approved as meeting the recital requirement for the Degree of Master of Music in Performance ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. Julia Bullard, Chair, Graduate Recital Committee ___________ _____________________________________________________ Date Dr. -

CUL Keller Archive Catalogue

HANS KELLER ARCHIVE: working copy A1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49 A1/1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49: independent work This section contains all Keller’s unpublished manuscripts dating from the 1940s, apart from those connected with his collaboration with Margaret Phillips (see A1/2 below). With the exception of one pocket diary from 1938, the Archive contains no material prior to his arrival in Britain at the end of that year. After his release from internment in 1941, Keller divided himself between musical and psychoanalytical studies. As a violinist, he gained the LRAM teacher’s diploma in April 1943, and was relatively active as an orchestral and chamber-music player. As a writer, however, his principal concern in the first half of the decade was not music, but psychoanalysis. Although the majority of the musical writings listed below are undated, those which are probably from this earlier period are all concerned with the psychology of music. Similarly, the short stories, poems and aphorisms show their author’s interest in psychology. Keller’s notes and reading-lists from this period indicate an exhaustive study of Freudian literature and, from his correspondence with Margaret Phillips, it appears that he did have thoughts of becoming a professional analyst. At he beginning of 1946, however, there was a decisive change in the focus of his work, when music began to replace psychology as his principal subject. It is possible that his first (accidental) hearing of Britten’s Peter Grimes played an important part in this change, and Britten’s music is the subject of several early articles.