Do Public-Good Oriented Courses in Independent Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goldman Sachs Philanthropy Fund | October 2012 SEPTEMBER 2011

Philanthropy Fund Families and Philanthropy An Overview for Donors Goldman Sachs Philanthropy Fund | October 2012 SEPTEMBER 2011 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Why should you engage your family in philanthropy? ..................................................................... 2 Who is in your “family?” ....................................................................................................................... 3 What values are core to your family philanthropy? .......................................................................... 4 How do you want to involve your family members in philanthropy? .............................................. 5 Which decision rules should you use in your family philanthropy? ................................................ 6 When should you start talking with your family about philanthropy? ............................................. 7 How can you engage your spouse/life partner in philanthropy?..................................................... 8 How can you engage your preschool- and elementary-age children in philanthropy? ................ 9 How can you engage your middle school- and high school-age children in philanthropy? ...... 10 How can you engage young adults in philanthropy? ..................................................................... 11 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................... -

Philanthropy Networks: Creating Value, Voice and Collective Impact 01 Foreword Who Said Net-Working Means Not-Working? Why This Publication and Why Now?

WINGS: Table of contents Worldwide Initiatives for Summary 01 Grantmaker Foreword 02 Introduction 04 Support 01 Creating and Conveying Value Summary 09 Value as a journey, not a destination 10 WINGS is a network of 150 Actively engaging stakeholders 10 philanthropy associations, networks, Creating value 12 academic institutions, support Designing responsive member services: Technology to engage 12 organizations, and funders in 50 Shaping the field through knowledge and practice 14 countries around the world whose Driving data solutions for membersand the sector 16 purpose is to strengthen, promote Conveying value 19 and provide leadership on the Communicating a value proposition 20 development of philanthropy and Assessing value of programs and services: The 4Cs 21 social investment. Amplifying Voice Thank you to dissemination partners 02 the United Philanthropy Forum and DAFNE- Donor and Foundations Summary 24 Network in Europe. Advocacy 25 The six-step approach 26 Common challenges 28 Thought leadership 28 What is a thought leader? 29 Priorities, framing and resources 30 03 Mobilizing Collective Impact Summary 33 Taking in the view 34 Landscaping and mapping 35 Cultivating connectivity in networks 36 Functions and practical approaches 37 Publication Author: Fostering collective impact 38 Filiz Bikmen, Constellations for Change Basic, moderate and complex approaches 39 Supervision: Benjamin Bellegy Coordination: Sarah Brown-Campello Conclusion 42 Editing: Resource Guide 44 Andrew Milner, Alliance Magazine WINGS Members Map: Networks & Associations 48 Design: Annex 50 Xouse Studio References 55 Summary One-minute version organizations serve their members or the sector? In reality, this is a false dichotomy, since serving their member or clients ultimately Value. -

Youth Philanthropy: a Framework of Best Practice

A Kellogg Foundation Publication Youth Philanthropy: A Framework of Best Practice Introduction "The philosophy of Although everyone knows that youth are the leaders of tomorrow, too youth as resources is few people 'recognize that they can be - and in many cases, already simple. If youth know are - the leaders of TODAY. that their community needs them, they will What can be done to better prepare young realize that they can be partners in solving people for this leadership role? some of society's most vexing problems and Youth philanthropy is an approach to empower and establish young perceive that their people as community leaders. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation has responsible action will supported a number of programs which successfully demonstrate that improve the experience in philanthropy encourages young people as community community's and their leaders. own situation." - Changing Perspectives, National Crime Prevention Council The Foundation is interested in sharing the lessons learned from these youth philanthropy programs and encouraging efforts to develop new programs in other communities. This "framework of best practice" in youth philanthropy is intended to serve as a decisionmaking guide for those interested in establishing similar efforts. Section 1 The BENEFITS of youth philanthropy programs Giving the power of philanthropy to young people allows teenagers to become valuable contributors now, as well as essential leaders for the future. Successful youth philanthropy programs can contribute to many positive outcomes (refer to Figures 1 and 2). The program responds to their need to belong and be a part of a peer group engaged in socially constructive activities. -

The Sustainable High Schools Kit

The Sustainable High Schools Kit A GGuideuide ttoo ImprovingImproving thethe SSocialocial andand EcologicalEcological Well-BeingWell-Being ooff YYourour SSchoolchool FFromrom tthehe SierraSierra YouthYouth CoalitionCoalition andand TThehe SSierraierra ClubClub BBCC EducationEducation ProgramProgram AAboutbout TThishis KitKit The 2007 edition of the original HHighigh SSchoolchool SSustainabilityustainability AAssessmentssessment FFrameworkramework (HSSAF) was written by Nicolas Parent with input from Aqueela Nanji, Emma Banks, participants in the Sustainable High Schools Symposium, members of the Sustainable High Schools Steering Committee and Sustainable Campuses Project staff Kerri Klein, Shari Hayne and Anjali Helferty. It was edited by SSierraierra YYouthouth CCoalitionoalition (SYC) National Director Rosa Kouri, SYC Executive Committee member Justin Grenier, and SSierraierra CClublub BBCC staff Emily Menzies, Jennifer Hoffman, Kerri Lanaway and Pharis Romero. This Sustainable High Schools Kit was written by Emily Menzies, with feedback from Summer 2007 Community Youth Action Gatherings, Kerri Lanaway, and Pharis Romero. This kit was designed and layed out by Pharis Romero. Cover art by Adrienne Dawn Enns Ink drawings by Mark Perrault RReproductioneproduction RightsRights TThehe SSustainableustainable HighHigh SSchoolschools KKitit © 2008 Sierra Club BC. All rights reserved. Permission is granted for educational, non-profit use only. For all other duplications, please contact the Sierra Club BC for permission prior to use. TThankhank -

Teen Philanthropists Award $33900 in Grants to Eight Nonprofits

FOR RELEASE: CONTACT: Alex Jacobs June 10, 2016 Marketing and Communications Officer (858) 279-2740 [email protected] TEEN PHILANTHROPISTS AWARD $33,900 IN GRANTS TO EIGHT NONPROFITS SECURING THE ESSENTIAL NEEDS FOR AT-RISK YOUTH SAN DIEGO – June 10, 2016 – The board of the Jewish Teen Foundation of San Diego (JTF), following a year-long experiential learning program about philanthropy, granted a total of $33,900 to eight nonprofits working to address essential needs for at-risk youth. JTF hosted a Community Check Presentation Ceremony celebrating the 2015-16 grantees and the teen participants on May 15. During the 2015-16 school year, twenty-five San Diego Jewish high schoolers collaborated to assess community needs, learn about nonprofit organizations and identify opportunities to effect change through strategic philanthropy. As a result, they awarded grants to ELEM/Youth in Distress in Israel, Just in Time for Foster Youth, Jewish Federation of San Diego, Monarch School, North County Lifeline, Reality Changers, Voices for Children and Yemin Orde Youth Village. Notable to this year’s grantmaking focus, the JTF program officers decided the best way to invest in these organizations was to fund infrastructure to ensure organizational sustainability. “What JTF participants are doing is very smart and forward thinking,” said Jeremy Pearl, Acting President and CEO of the Jewish Community Foundation. “They are helping to give voice to the narrative that strong infrastructure means a strong organization. JTF is a program of the Jewish Community Foundation (JCF) of San Diego, which has a 19-year history of providing philanthropy education programs designed uniquely for teens. -

Scanning the Landscape of Youth Philanthropy

SCANNING THE LANDSCAPE OF YOUTH PHILANTHROPY: OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STRENGTHENING A GROWING FIELD AUTHORS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Jen Bokoff, Director of GrantCraft The authors would like to thank the Frieda C. Fox Family Amanda Dillon, Manager of Strategic Philanthropy Foundation and its special project, Youth Philanthropy Connect, for its generous support of this work. Special ILLUSTRATOR thanks to Ellen Blanchard, Brenda Henry-Sanchez, Amanda Lyons, Visuals for Change Annie Hernandez, Luana Nissan, Erin Nylen-Wysocki, Lisa Philp, and Jamie Semel, who reviewed drafts and PHOTO CREDITS provided thoughtful and constructive feedback. Cover image, page 19: Ross Moore Page 12, 15: Youth Speak Media Solutions Additional thanks to Foundation Center staff members Denise McLeod, Sarah Jo Neubauer, and Mary Ann ABOUT FOUNDATION CENTER Santos, who conducted scans or provided guidance, and to Christine Innamorato, Cheryl Loe, Betty Established in 1956, Foundation Center is the Saronson, Vanessa Schnaidt, and Davis Winslow, leading source of information about philanthropy who helped with production. worldwide. Through data, analysis, and training, it connects people who want to change the world We would like to thank all the individuals who joined to the resources they need to succeed. Foundation us for a youth philanthropy convening in May 2014 and Center maintains the most comprehensive database contributed their energy, thoughts, and new ideas to on U.S. and, increasingly, global grantmakers and this project. They include Dave Aldrich, Elizabeth Cahill, their grants—a robust, accessible knowledge bank for Rob Collier, Steve Culbertson, Shirish Dayal, Siah the sector. It also operates research, education, and Dowlatshahi, Alan Fox, Daveen Fox, Rahsaan Harris, training programs designed to advance knowledge Mark Larimer, Nakisha Lewis, Luana Nissan, Diana of philanthropy at every level. -

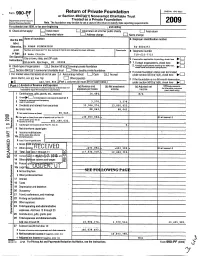

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Departmerp of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this retu rn to satisfy state reporting requirem ents. 2009 For calendar year 2009 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply. L_J Initial return L_J Initial return of a former public charity L_J Final return LI Amended return 0 Address change L1 Name change of foundation Use the IRS Name A Employer Identification number label. Otherwise , L POMAR FOUNDATION 84-6002373 print Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail Is not delivered to street address) Room/sulte B Telephone number or type . 0 Lake Circle 719-633-7733 See Specifi City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application Is pending , check here Instructions . ► olorado Springs, CO 80906 0 1 . Foreign organizations , check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, p.0 H Check type of organization: x Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation Section 4947( 0)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Q Other taxable private foundation E If private foun dation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual under section 507 (b)(1)(A), check here ► (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16 ) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 443, 500 , 866 . -

Building Effective Youth-Adult Partnerships: a Webinar for Adults

March 2016 Newsletter Happy March! Check out all of the opportunities coming up to connect with your fellow network of youth philanthropists! Whether it be remote learning or in-person conferences, we are excited to have you all be able to share and learn from each other, while connecting with your peers. Don't forget to register for one of our upcoming webinars or conferences. Details below! -Team YPC Building Effective Youth-Adult Partnerships: A Webinar for Adults Three YPC Leadership Team members will be speaking on a webinar with Daniel Horgan, a youth development expert, in partnership with Exponent Philanthropy! Learn how to build and sustain effective youth-adult partnerships with this webinar that will give you tangible tools and resources to give youth leadership skills and facilitate meaningful investments of time, talent, and treasure. Register for the FREE webinar here! Thursday, March 31, 2 p.m. EST Alison Pakradooni (pictured left) is a sophomore at Temple University and has been involved in her family foundation, The Andrus Family Fund, since she was 13 years old. As only a junior in high school, Gaby Baum (pictured right) has been active in the Jewish Teen Funders Network program Teen Tzedakah Korps, and the NJY camps philanthropy program. Lexi Laginess (pictured left) started her philanthropic career as a sophomore with the Bedford Community Foundation. Now a senior, she is involved in numerous youth-oriented organizations. (Check out her profile below!) This webinar is the first of the four-part series Enhancing Youth Engagement in Philanthropy. Check out the entire series here! Meet Two Youth Philanthropists: Leadership Team Members Kylie Semel & Lexi Leginess When Kylie Semel was 11 years old, she had an idea. -

Magnified Giving, a Leader in Youth Philanthropy Since 2008 Has Educated Over 23,000 Students Utilizing Our Curriculum and Service-Learning Method

Magnified Giving, a leader in youth philanthropy since 2008 has educated over 23,000 students utilizing our curriculum and service-learning method. The Mayerson Foundation has provided funding and guidance to Magnified Giving to continue supporting and leading our community in this work. The Mayerson Foundation’s history in service-learning is rich and meaningful, forever impacting the lives of our youth and community members. Requests are received from schools for assistance to create opportunities for service hours, integrate service in the academic curriculum, and enhance the experience for the student with reflection activities. Magnified Giving is honored to continue fulfilling these services once provided by the Mayerson Foundation. We will offer support and leadership to Middle School and High School students and teachers for the following programs: Student Service Conference and Challenge This annual event is a day-long workshop bringing students, teachers and non-profits together to energize all for an active and inspirational school year of service-learning and deep impact within the community. Throughout the day students and teachers select meaningful breakout sessions to attend sharing ideas in service and service-learning, cross-educating one another with best practices, and connecting with various non-profit organizations to learn how teens may engage with their organization and mission in the community. The recent Global Pandemic has exposed all of us to the opportunity for virtual connectivity allowing us to get creative in ways to strengthen relationships in our region. The Student Service Conference (SSC) will continue to provide new opportunities for service-learning development and peer connectivity. -

2000 Vw Beetle Radio Code the Name Eos Was Derived from Eos , the Greek Goddess of the Dawn

2000 vw beetle radio code The name Eos was derived from Eos , the Greek goddess of the dawn. However, a limited number of base trim models were sold as models of in the United States. Unlike the Cabrio, which was a convertible version of the Golf hatchback, the Eos was a standalone model with all new body panels, although it shared the platform and components from the Volkswagen Golf Mk5. The wheelbase matches the Golf Mk5 and Jetta. The Eos incorporates into its five piece folding roof an integrated and independently sliding glass sunroof — making the Eos the only retractable hardtop of this kind. The roof folds automatically into the trunk in twenty five seconds, thereby reducing trunk space from The design of the roof system is complex with its own hydraulic control system and numerous rubber seals. Periodic maintenance must be done to keep the seals conditioned so that they function properly. Proper body alignment is critical for proper top function. A facelifted Volkswagen Eos appeared in October , and went on sale as a model of outside Europe. This facelift includes a revised front and rear fascias, headlights and tail lights, side mirrors, as well as new wheel designs. The White Night edition was a special edition with custom wheels, custom black interior and a black and white colour scheme package. Other features include black mirror covers, radiator grille and trim strips, black Nappa leather seats, door and side trim and black steering wheel with light coloured seams, trim strips and radio trim in candy white, sill panel strips with white night letters. -

Global Youth Philanthropy Summit

YOUTH COMMUNITY PHILANTHROPY Global Summit Report 2014 Published October 2014 For Youth and Community Charles Stewart Mott believed that every person exists in a kind of informal partnership with his or her community. He recognized that both can reach their full potential only if they are thriving together. That’s why the Mott Foundation supports institutions that help to build strong relationships between individuals and their communities. Over the past 35 years, we’ve invested more than $150 million in the development of community foundations and in community philanthropy. Recently, we supported a series of projects marking the 100th anniversary of community foundations, including the Global Youth Community Philanthropy Summit. As community foundations enter into their next century, we believe that engaging youth in philanthropy will be vital to the field’s continued success and relevance. The Global Summit provided the opportunity for young people from around the world to forge new connections, share fresh ideas and learn from each other. My hope is that this process continues. As the Mott Foundation has learned from decades of work in the field, global connections and learning definitely lead to community-level improvement. We offer thanks to the Council of Michigan Foundations and the Council on Foundations for organizing the Summit and, most important, to the participants for joining us and sharing. Nicholas S. Deychakiwsky Program Officer, Civil Society The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The spirit of generosity and collaboration is alive in young people around the world. In convening the Global Youth Community Philanthropy Summit, we had the opportunity to capture the voices and experiences of youth philanthropy participants, practitioners and thought leaders. -

Youth-Adult Partnerships: a Training Manual

youth-adult partnerships: a training manual • Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development • National 4-H Council • National Network for Youth • Youth Leadership Institute The authors and partners encourage the reproduction of this material for usage in trainings and workshops, provided that copy- right and source information is cited and credited. Any reproduction, translation, or transmission of this material for financial gain, in any forms or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without permis- sion of the authors, is prohibited. ©2003 Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development, National Network for Youth, Youth Leadership Institute. This edition was printed in August, 2003. youth-adult partnerships - a training manual page 1 This manual is the culmination of contributions from many individuals and organizations. All four partner organizations—the National 4-H Council, the National Network for Youth, and the Youth Leadership Institute, with the leadership of the Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development—are grateful to the dedication, hard work, and creativity of the people involved in the development of this training manual. The Lead Team played a critical role in keeping this project focused and moving forward; the team was bolstered by the invaluable vision and initial conceptual and prac- tical framework for the manual provided by the Design Team. Members of the Lead and Design Teams included the following people: Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development: Keri Dakow, Hartley Hobson, Lyndsey Merchant, Ashley Price, Amy Weisenbach, Carla Roach (facilitator), and Kristen Spangler (facilitator); National Network for Youth: Ingrid Drake, Megan Klein, Jo Mestelle, and Tony Zepeda; Youth Leadership Institute: Eric Rowles, Maureen Sedonean, Monica Alatorre, about Gina Rivera-Cater, Saun-Toy Trotter, and Khin Mae Aung.