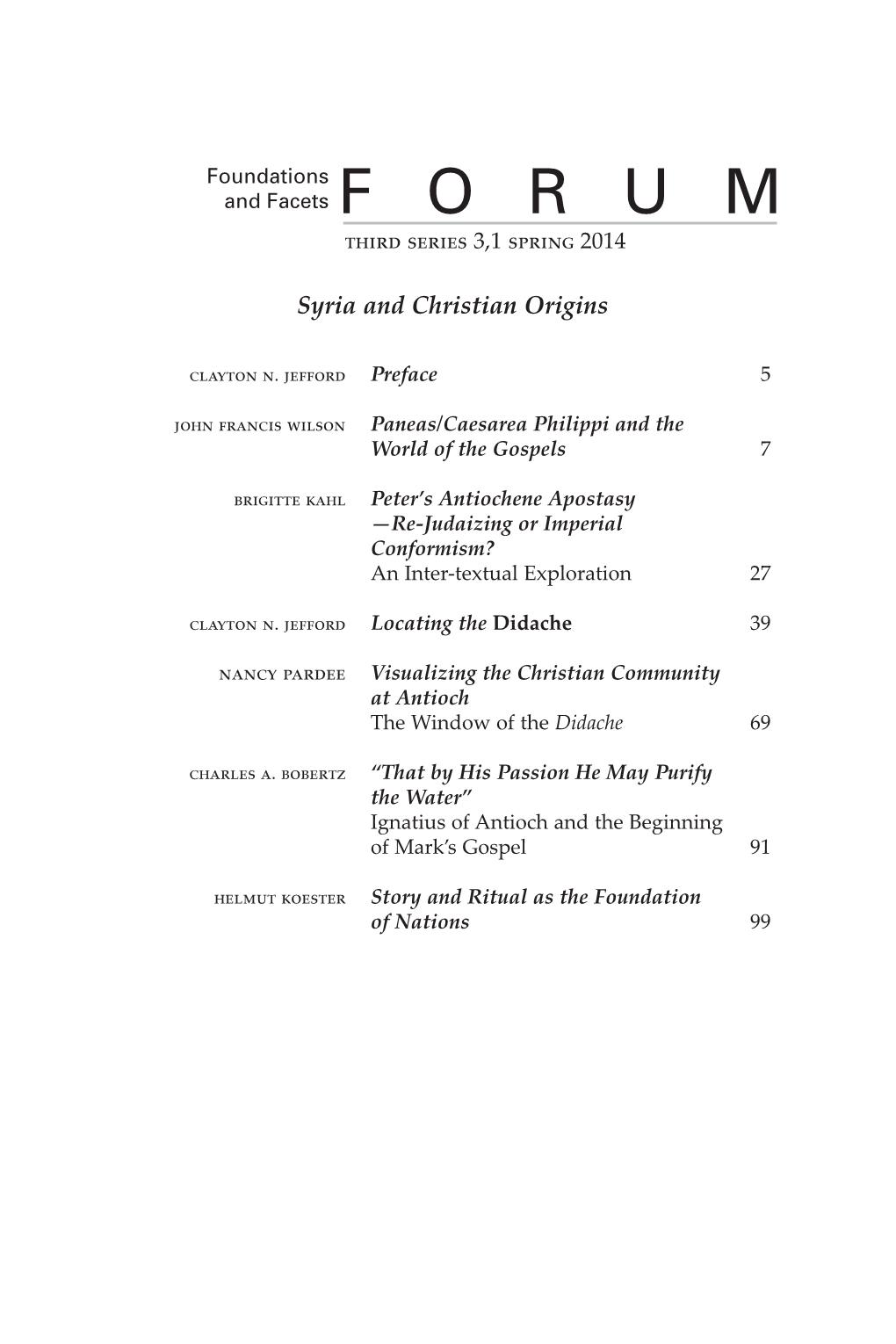

Forum 3,1 Syria and Christian Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petition for Marriage Permission Or Dispensation

Form M2 Revised 9/2009 DIOCESE OF SPOKANE PETITION FOR MARRIAGE PERMISSION OR DISPENSATION GROOM BRIDE Name Name Address Address City, State City, State Date of Birth Date of Birth RELIGION Catholic Catholic Parish: Parish: Place: Place: Baptized non-Catholic Baptized non-Catholic Denomination: Denomination: Unbaptized Unbaptized Scheduled date and place for marriage: The following dispensation and permissions may be granted by the pastor for marriages celebrated within the territory his parish. Otherwise, the petition is submitted to the Local Ordinary. A. Disparity of Cult (C. 1086, a Catholic and a non-baptized person). See reverse side. B. Mixed Religion (and, if necessary, disparity of cult, C. 1124). See reverse side. C. Natural obligations from a prior union (C. 1071 3°). Marriage is permitted only when the pastor or competent authority is sure that these obligations are being fulfilled. D. Permission to marry when conditions are attached to a declaration of nullity—granted only if these stipulations have been fulfilled. (Cf. C. 1684) By virtue of the faculties granted to pastors of the Diocese of Spokane, I hereby grant the above indicated permissions/dispensation. Pastor: Date: (This document is retained in the prenuptial file) See p. 2 of this form for dispensations and permissions reserved to the Local Ordinary (Diocesan bishop, Vicar General or their delegate). Page 1 of 2 Form M2 In cases of Mixed Religion (Catholic and a baptized non-Catholic) or Disparity of Cult, the Catholic party is to make the following promise in writing or orally: “I reaffirm my faith in Jesus Christ and, with God’s help, intend to continue living that faith in the Catholic Church. -

Applying the Doctrine of Revocation by Divorce to Life Insurance Policies Alan S

Cornell Law Review Volume 73 Article 6 Issue 3 March 1988 Applying the Doctrine of Revocation by Divorce to Life Insurance Policies Alan S. Wilmit Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan S. Wilmit, Applying the Doctrine of Revocation by Divorce to Life Insurance Policies, 73 Cornell L. Rev. 653 (1988) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol73/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPLYING THE DOCTRINE OF REVOCATION BY DIVORCE TO LIFE INSURANCE POLICIES The Uniform Probate Code states: "If after executing a will the testator is divorced or his marriage annulled, the divorce.., revokes any disposition or appointment of property made by the will to the former spouse .... 1 Forty-four states have similar revocation-by- divorce statutes.2 The revocation statutes recognize that "[d]ivorce usually repre- sents a stormy parting, where the last thing one of the parties wishes is to have an earlier will carried out giving everything to a former 1 UNIF. PROB. CODE § 2-508 (1982). Section 2-508 states in full: If after executing a will the testator is divorced or his marriage an- nulled, the divorce or annulment revokes any disposition or appointment of property made by the will to the former spouse, any provision confer- ring a general or special power of appointment on the former spouse, and any nomination of the former spouse, as executor, trustee, conserva- tor, or guardian, unless the will expressly provides otherwise. -

Around the Sea of Galilee (5) the Mystery of Bethsaida

136 The Testimony, April 2003 to shake at the presence of the Lord. Ezekiel that I am the LORD” (v. 23). May this time soon concludes by saying: “Thus will I magnify My- come when the earth will be filled with the self, and sanctify Myself; and I will be known in knowledge of the glory of the Lord and when all the eyes of many nations, and they shall know nations go to worship the King in Jerusalem. Around the Sea of Galilee 5. The mystery of Bethsaida Tony Benson FTER CAPERNAUM, Bethsaida is men- according to Josephus it was built by the tetrarch tioned more times in the Gospels than Philip, son of Herod the Great, and brother of A any other of the towns which lined the Herod Antipas the tetrarch of Galilee. Philip ruled Sea of Galilee. Yet there are difficulties involved. territories known as Iturea and Trachonitis (Lk. From secular history it is known that in New 3:1). Testament times there was a city called Bethsaida Luke’s account of the feeding of the five thou- Julias on the north side of the Sea of Galilee, but sand begins: “And he [Jesus] took them [the apos- is this the Bethsaida of the Gospels? Some of the tles], and went aside privately into a desert place references to Bethsaida seem to refer to a town belonging to the city called Bethsaida” (9:10). on the west side of the lake. A tel called et-Tell 1 The twelve disciples had just come back from is currently being excavated over a mile north of their preaching mission and Jesus wanted to the Sea of Galilee, and is claimed to be the site of be able to have a quiet talk with them. -

Suspension and Revocation Chapter 23 Major Offenses

MRS Title 29-A, Chapter 23. MAJOR OFFENSES - SUSPENSION AND REVOCATION CHAPTER 23 MAJOR OFFENSES - SUSPENSION AND REVOCATION SUBCHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS §2401. Definitions As used in this chapter, unless the context otherwise indicates, the following terms have the following meanings. [PL 1993, c. 683, Pt. A, §2 (NEW); PL 1993, c. 683, Pt. B, §5 (AFF).] 1. Alcohol and drug program. "Alcohol and drug program" means the alcohol and other drug education, evaluation and treatment program administered by the Department of Health and Human Services under Title 5, chapter 521, subchapter 5. [PL 2011, c. 657, Pt. AA, §77 (AMD).] 2. Alcohol level. "Alcohol level" means either grams of alcohol per 100 milliliters of blood or grams of alcohol per 210 liters of breath. [PL 2009, c. 447, §32 (AMD).] 3. Chemical test or test. "Chemical test" or "test" means a test or tests used to determine alcohol level or the presence of a drug or drug metabolite by analysis of blood, breath or urine. [PL 2013, c. 459, §1 (AMD).] 4. Drugs. "Drugs" means scheduled drugs as defined under Title 17‑A, section 1101. The term "drugs" includes any natural or artificial chemical substance that, when taken into the human body, can impair the ability of the person to safely operate a motor vehicle. [PL 1995, c. 145, §1 (AMD).] 5. Failure to submit to a test, fails to submit to a test or failed to submit to a test. "Failure to submit to a test," "fails to submit to a test" or "failed to submit to a test" means failure to comply with the duty to submit to and complete a chemical test under section 2521 or 2525. -

DCC ECRM Supervision Supervision Process Revocation.Pdf

Electronic Case Reference Manual > Supervision > DCC Supervision > Supervision Process > Revocations Investigation/Decision Pre-Preliminary Hearing Waived Hearings Preliminary Hearings Post-Preliminary Hearing Final Revocation Hearing Appeals Revocation and Reinstatement Orders Special Revocation Procedures Legal Rules, Aids & Guidelines INVESTIGATION/DECISION .01 AUTHORITY Wisconsin Administrative Code Sections HA 2 Wisconsin Administrative Code DOC 331 Wisconsin Statutes 302.11 .02 GENERAL STATEMENT An offender's supervision may be revoked if the offender violates a rule or condition of supervision. When supervision is revoked, the offender is either: returned to court for sentencing, or transported to a correctional facility to begin serving the sentence indicated by the Court. Protection of the public is the primary consideration in any revocation decision. .03 TIME FRAMES These time frames only apply to cases where an Order to Detain (DOC-212) has been authorized by the Department. Electronic Case Reference Manual > Supervision > DCC Supervision > Supervision Process > Revocations If the offender is in custody, the offender should be interviewed within 3 working days. The original 3 working day detention for investigation can be extended by completing a Detention Extension Request (DOC-212). The supervisor may extend detention for 3 working days. The Regional Chief may extend for an additional 5 working days. If further extension is necessary, the Administrator or designee may approve any additional time in increments of five days. Once a decision to revoke has been made, the Notice of Violation and Hearing Rights (DOC-414) shall be served within 2 working days. If revocation will proceed and an ATR is not likely at the time of issuance of the DOC-414, the Revocation Notification to Victim (DOC-2938) along with a Revocation Proceeding Fact Sheet for Victims shall be sent to the victim. -

HOUSE BILL No. 2038

{As Amended by Senate Committee of the Whole} Session of 2019 HOUSE BILL No. 2038 By Committee on Judiciary 1-17 1 AN ACT concerning inheritance rights; relating to revocation upon 2 divorce. 3 4 Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Kansas: 5 Section 1. (a) As used in this section: 6 (1) "Disposition or appointment of property" includes a transfer of an 7 item of property or any other benefit to a beneficiary designated in a 8 governing instrument. 9 (2) "Divorce or annulment" means any divorce or annulment, or any 10 dissolution or declaration of invalidity of a marriage that would exclude 11 the spouse as a surviving spouse. A decree of separation that does not 12 terminate the parties' marital status is not a divorce for purposes of this 13 section. 14 (3) "Divorced individual" includes an individual whose marriage has 15 been annulled. 16 (4) "Governing instrument" means a document executed by the 17 divorced individual before the divorce or annulment of such individual's 18 marriage to such individual's former spouse. 19 (5) "Relative of the divorced individual's former spouse" means an 20 individual who is related to the divorced individual's former spouse by 21 blood, adoption or affinity and who, after the divorce or annulment, is not 22 related to the divorced individual by blood, adoption or affinity. 23 (6) "Revocable," with respect to a disposition, appointment, provision 24 or nomination, means one under which the divorced individual, at the time 25 of the divorce or annulment, was alone empowered, by law or under the 26 governing instrument, to cancel the designation in favor of such 27 individual's former spouse or former spouse's relative, whether or not the 28 divorced individual was then empowered to designate such individual's 29 self in place of such individual's former spouse or in place of such 30 individual's former spouse's relative and whether or not the divorced 31 individual then had the capacity to exercise the power. -

Revocation of Trusts by Consent of the Beneficiaries

Indiana Law Journal Volume 36 Issue 1 Article 4 Fall 1960 Revocation of Trusts by Consent of the Beneficiaries Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Recommended Citation (1960) "Revocation of Trusts by Consent of the Beneficiaries," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 36 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol36/iss1/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES REVOCATION OF TRUSTS BY CONSENT OF THE BENEFICIARIES The settlor of an inter vivos trust generally cannot revoke it unless he has reserved in the trust instrument a power of revocation.' A well recognized exception occurs, however, where all persons who have a "beneficial interest" in the trust give their consent that the settlor can revoke the trust even though the instrument declares that the trust shall be irrevocable.' This exception, called the consent rule, is derived from the English common-law and has been adopted throughout most of the United States3 whenever the question of revocation of a trust by the con- sent of the beneficiaries has arisen. Generally, when a settlor has granted property rights he cannot resume his former status merely because he later decides his disposition was unwise.4 But if the settlor and all the beneficiaries no longer wish the trust to be continued, there is no reason for the court to insist that its terms be carried out.5 The rule is simple enough as stated, but courts have experienced con- siderable difficulty in determining who are persons beneficially interested. -

Hasmonean” Family Tree

THE “HASMONEAN” FAMILY TREE Hasmoneus │ Simeon │ John │ Mattathias ┌──────────────┬─────────────────────┼─────────────────┬─────────┐ John Simon Judas Maccabee Eleazar Jonathan Murdered: Murdered: KIA: KIA: Murdered: 160/159 BC 134 BC 160 BC 162 BC 143 BC ┌────────┬────┴────┐ Judas John Hyrcanus Murdered: Murdered: Died: 134 BC 135 BC 104 BC ├──────────────────────┬─────────────┐ Aristobulus ═ Salome Alexander Antigonus Alexander ═══════ Salome Alexander Declared Himself “King”: Murdered: Declared “King”: Declared “Regent”: 104 BC 103 BC 103 BC 76 BC Died: Died: 103 BC 76 BC ┌──────┴──────┐ Hyrcanus II Aristobulus II Declared High Priest: 76 BC 1 THE “HASMONEAN” DYNASTY OF SIMON THE HIGH PRIEST 142 BC Simon, the last of the sons of Mattathias, was declared High Priest & “Ethnarch” (ruler of one’s own ethnic group) of the Jews by Demetrius II, King of the Seleucid Empire. 138 BC After Demetrius II was captured by the Parthians, his brother, Antiochus VII, affirmed Simon’s High Priesthood & requested assistance in dealing with Trypho, a usurper of the Seleucid throne. “King Antiochus to Simon the high priest and ethnarch and to the nation of the Jews, greetings. “Whereas certain scoundrels have gained control of the kingdom of our ancestors, and I intend to lay claim to the kingdom so that I may restore it as it formerly was, and have recruited a host of mercenary troops and have equipped warships, and intend to make a landing in the country so that I may proceed against those who have destroyed our country and those who have devastated many cities in my kingdom, now therefore I confirm to you all the tax remissions that the kings before me have granted you, and a release from all the other payments from which they have released you. -

The Christology of Mark

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1972 The Christology of Mark Gregory L. Jackson Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Gregory L., "The Christology of Mark" (1972). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1511. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1511 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHRISTOLOGY OF MARK by Gregory L. Jackson A Thesis submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree MASTER OF DIVINITY from Waterloo Lutheran Seminary Waterloo, Ontario May 30, 1972 n^^ty of *he Library "-'uo University College UMI Number: EC56448 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI EC56448 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml -

Family Lesson 52

Family Lesson 52 Principle: We must repent of sin. God was Luke 3:2b pleased with Jesus. Jesus came to save. 2b At this time a message from God came to Bible Character(s): Jesus and John the John son of Zechariah, who was living in the Baptist wilderness. Scripture Reference: Luke 3:1-18, Matthew 3:1-17 Matthew 3:4 4 John’s clothes were woven from coarse 1. Worship - Gather your family and play the camel hair, and he wore a leather belt around worship video found on the curriculum resource his waist. For food he ate locusts and wild page. Have fun, sing loudly, and follow along with honey. the motions! 2. Skit Video - Watch the skit video with your John is very different from the religious leaders family to hear a special message about what you mentioned in Luke 3. He has been living in the will be learning this weekend. wilderness, where God prepares him to share 3. Bible Lesson - Read through the lesson with his message with the people and prepare them your family. The bold font is meant to be read for Jesus. John is more like the people he aloud along with the Scripture references. preached to, more ordinary, than the religious leaders. John is not the most powerful man of Bible Lesson that time. Annas and Caiaphas have more power than John, but God chooses to use John as his Last week, we studied about Jesus when he was messenger. a young boy. Today, we are going to read about John the Baptist. -

Julia Wilker University of Pennsylvania

ELECTRUM * Vol. 25 (2018): 127–145 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.18.007.8927 www.ejournals.eu/electrum BETWEEN EMPIRES AND PEERS: HASMONEAN FOREIGN POLICY UNDER ALEXANDER JANNAEUS Julia Wilker University of Pennsylvania Abstract: During the reign of Alexander Jannaeus (103–76 BCE), Judea underwent a number of signifi cant changes. This article explores one of them: the fundamental shift in foreign policy strategy. This shift becomes most apparent in the king’s decision to not renew the alliance with Rome, which had been a hallmark of Hasmonean foreign policy since the days of Judas Mac- cabaeus. However, a close analysis of Alexander Jannaeus’ policy regarding other foreign powers demonstrates that the end of the Judean-Roman alliance did not happen in a vacuum. It is shown that under Alexander Jannaeus, the Hasmonean state adopted a different strategy towards imperial powers by focusing on deescalation and ignorance rather than alliances. In contrast, interactions with other rising states in the vicinity, such as the Nabateans and Itureans, increased. This new orientation in foreign policy refl ected changes in Hasmonean identity and self-defi nition; Judea did not need imperial support to maintain its independence anymore but strived to increase its status as a regional power. Key words: Hasmoneans, Alexander Jannaeus, Jewish-Roman relations, foreign relations. The reign of Alexander Jannaeus (103–76 BCE) constituted a seminal period in the his- tory of Hellenistic Judea; his rule signifi es both the acme and a turning point of the Has- monean state. The length of his tenure as king – second only to that of his father, John Hyrcanus (135–105/104 BCE) – stands in signifi cant contrast to that of his predecessor, Aristobulus I, who died after having ruled for less than a year. -

Judaean Rulers and Notable Personnages

Chronology of Syria and Palestine, 40 BCE – 70 CE Governors of Governors of Governors of Iturea, Trachonitis, Judaea Galilee/Perea Paneas & Batanaea Judaean High Lysanias (Tetrarch) LEGEND Priests (including Chalcis and Abila) Ananelus 37-36 BCE 40–36 BCE Aristobulus III 36 BCE High priests of Jerusalem Cleopatra VII Philopater Ananelus 36-30 BCE (Pharaoh of Egypt) 36–30 Rulers of Nabatea Roman prefects Roman 30 BCE Emperors Governors of The status of this territory Herodian monarchs between Cleopatras’ death and Jesus ben Fabus 30–23 BCE Roman Syria Zenodorus’ administration is Marcus Terentius Varro 25–23 uncertain. Roman legates Herod the Great (King) (part of the kingdom of Zenodorus (Tetrarch) 40/39–4 BCE Judaea) 23–20 BCE Roman proconsuls 20 BCE Obodas III Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa 39–9 BCE 23–13 Other rulers Zenodorus’ territories were incorporated into Herod’s Simon ben Boethus 23–5 BCE kingdom in 20 BCE. Trachonitis, Auranitis and Batanaea were Marcus Titius given to Herod earlier, in 23 BCE. 13–9 Governors of 10 BCE Jamnia, Ashdod & Gaius Sentius Saturninus 9–7/6 Phasaelis Augustus Publius Quinctilius Varus 27 BCE – 14 CE 7/6–4 Formerly part of Herod’s kingdom Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus** 4–1 BCE Matthias ben Theophilus 5–4 BCE Joazar ben Boethus 4 BCE Herod Archelaus (Ethnarch) 1 CE Eleazar ben Boethus 4–3 BCE Gaius Julius Caesar Vipsanianus Jesus ben Sie 3 BC– ? 4 BCE – 6 CE 1 BCE – 4 CE Joazar ben Boethus ?–6 CE Salome I (Toparch) 4 BCE – 10 CE Lucius Volusius Saturninus 4–5 Coponius 6–9 Publius Sulpicius Quirinius