Pas in Cardiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Excellence in Cardiology

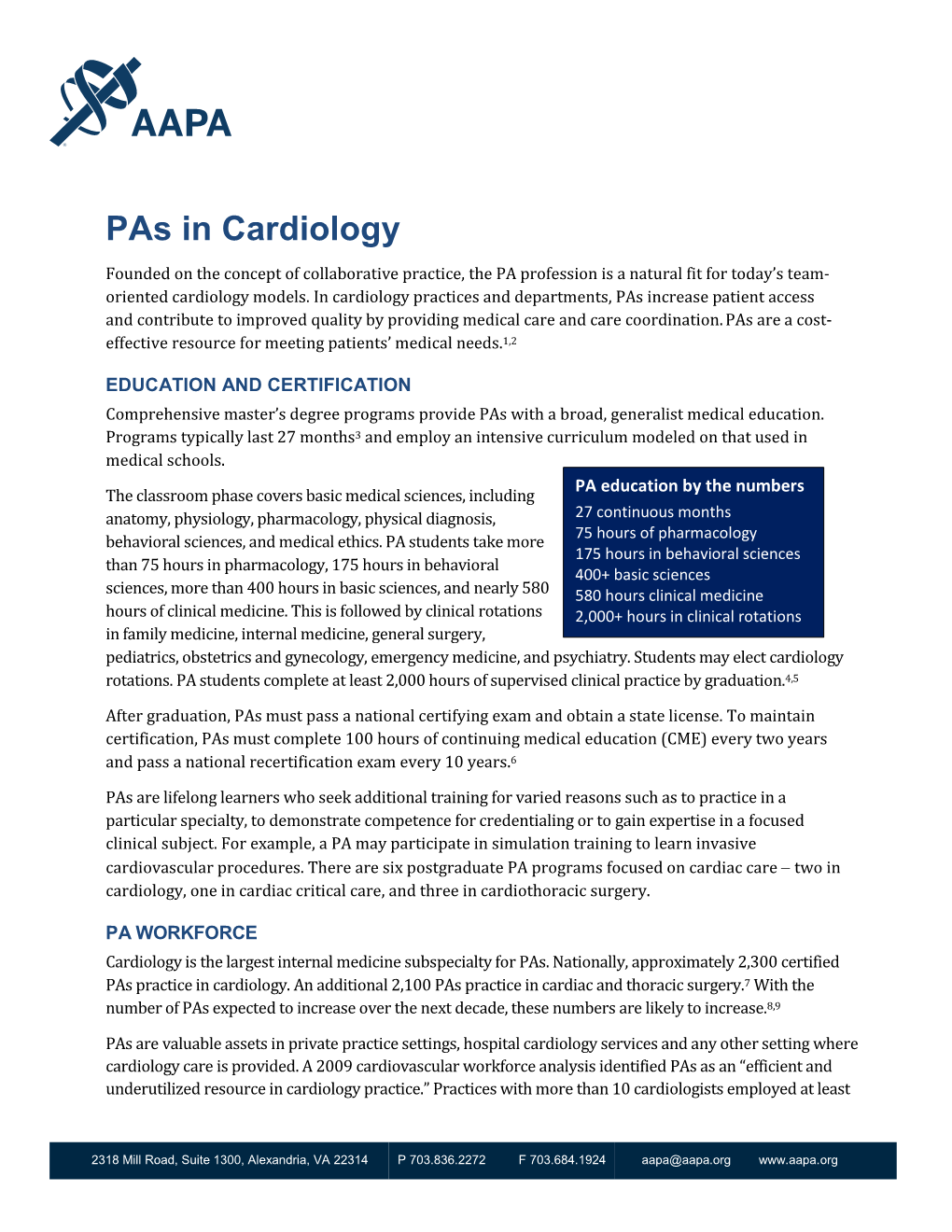

Clinical Excellence in Cardiology Roy C. Ziegelstein, MD* A recent study identified 7 domains of clinical excellence on the basis of interviews with “clinically excellent” physicians at academic institutions in the United States: (1) commu- nication and interpersonal skills, (2) professionalism and humanism, (3) diagnostic acu- men, (4) skillful negotiation of the health care system, (5) knowledge, (6) taking a scholarly approach to clinical practice, and (7) having passion for clinical medicine. What constitutes clinical excellence in cardiology has not previously been defined. The author discusses clinical excellence in cardiology using the framework of these 7 domains and also considers the additional domain of clinical experience. Specific aspects of the domains of clinical excellence that are of greatest relevance to cardiology are highlighted. In conclusion, this discussion characterizes what constitutes clinical excellence in cardiology and should stimulate additional discussion of the topic and an examination of how the domains of clinical excellence in cardiology are related to specific patient outcomes. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. (Am J Cardiol 2011;108:607–611) On the basis of interviews with 24 academic physicians and clinical excellence has not been clearly demonstrated. deemed “clinically excellent,” Christmas et al1 identified 7 For example, the compliance of hospitals with performance domains of clinical excellence relevant to all disciplines in measures is not associated with improved heart failure out- medicine: (1) communication and interpersonal skills, (2) comes.10,11 The speed with which an interventional cardi- professionalism and humanism, (3) diagnostic acumen, (4) ologist achieves reperfusion of the culprit vessel, the so- skillful negotiation of the health care system, (5) knowl- called door-to-balloon time, is an important performance edge, (6) taking a scholarly approach to clinical practice, measure in the treatment of patients with acute ST-segment and (7) having passion for clinical medicine. -

Internal Medicine Milestones

Internal Medicine Milestones The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Implementation Date: July 1, 2021 Second Revision: November 2020 First Revision: July 2013 ©2020 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) All rights reserved except the copyright owners grant third parties the right to use the Internal Medicine Milestones on a non-exclusive basis for educational purposes. Internal Medicine Milestones The Milestones are designed only for use in evaluation of residents in the context of their participation in ACGME-accredited residency programs. The Milestones provide a framework for the assessment of the development of the resident in key dimensions of the elements of physician competency in a specialty or subspecialty. They neither represent the entirety of the dimensions of the six domains of physician competency, nor are they designed to be relevant in any other context. ©2020 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) All rights reserved except the copyright owners grant third parties the right to use the Internal Medicine Milestones on a non-exclusive basis for educational purposes. i Internal Medicine Milestones Work Group Eva Aagaard, MD, FACP Jonathan Lim, MD Cinnamon Bradley, MD Monica Lypson, MD, MHPE Fred Buckhold, MD Allan Markus, MD, MS, MBA, FACP Alfred Burger, MD, MS, FACP, SFHM Bernadette Miller, MD Stephanie Call, MD, MSPH Attila Nemeth, MD Shobhina Chheda, MD, MPH Jacob Perrin, MD Davoren Chick, MD, FACP Raul Ramirez Velazquez, DO Jack DePriest, MD, MACM Rachel Robbins, MD Benjamin Doolittle, MD, MDiv Jacqueline Stocking, PhD, MBA, RN Laura Edgar, EdD, CAE Jane Trinh, MD Christin Giordano McAuliffe, MD Mark Tschanz, DO, MACM Neil Kothari, MD Asher Tulsky, MD Heather Laird-Fick, MD, MPH, FACP Eric Warm, MD Advisory Group Mobola Campbell-Yesufu, MD, MPH Subha Ramani, MBBS, MMed, MPH Gretchen Diemer, MD Brijen Shah, MD Jodi Friedman, MD C. -

Anemia in Heart Failure - from Guidelines to Controversies and Challenges

52 Education Anemia in heart failure - from guidelines to controversies and challenges Oana Sîrbu1,*, Mariana Floria1,*, Petru Dascalita*, Alexandra Stoica1,*, Paula Adascalitei, Victorita Sorodoc1,*, Laurentiu Sorodoc1,* *Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy; Iasi-Romania 1Sf. Spiridon Emergency Hospital; Iasi-Romania ABSTRACT Anemia associated with heart failure is a frequent condition, which may lead to heart function deterioration by the activation of neuro-hormonal mechanisms. Therefore, a vicious circle is present in the relationship of heart failure and anemia. The consequence is reflected upon the pa- tients’ survival, quality of life, and hospital readmissions. Anemia and iron deficiency should be correctly diagnosed and treated in patients with heart failure. The etiology is multifactorial but certainly not fully understood. There is data suggesting that the following factors can cause ane- mia alone or in combination: iron deficiency, inflammation, erythropoietin levels, prescribed medication, hemodilution, and medullar dysfunc- tion. There is data suggesting the association among iron deficiency, inflammation, erythropoietin levels, prescribed medication, hemodilution, and medullar dysfunction. The main pathophysiologic mechanisms, with the strongest evidence-based medicine data, are iron deficiency and inflammation. In clinical practice, the etiology of anemia needs thorough evaluation for determining the best possible therapeutic course. In this context, we must correctly treat the patients’ diseases; according with the current guidelines we have now only one intravenous iron drug. This paper is focused on data about anemia in heart failure, from prevalence to optimal treatment, controversies, and challenges. (Anatol J Cardiol 2018; 20: 52-9) Keywords: anemia, heart failure, intravenous iron, ferric carboxymaltose, quality of life Introduction g/dL in men) (2). -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Training in Nuclear Cardiology

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY VOL.65,NO.17,2015 ª 2015 BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATION ISSN 0735-1097/$36.00 PUBLISHED BY ELSEVIER INC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.019 TRAINING STATEMENT COCATS 4 Task Force 6: Training in Nuclear Cardiology Endorsed by the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology Vasken Dilsizian, MD, FACC, Chair Todd D. Miller, MD, FACC James A. Arrighi, MD, FACC* Allen J. Solomon, MD, FACC Rose S. Cohen, MD, FACC James E. Udelson, MD, FACC, FASNC 1. INTRODUCTION ACC and ASNC, and addressed their comments. The document was revised and posted for public comment 1.1. Document Development Process from December 20, 2014, to January 6, 2015. Authors 1.1.1. Writing Committee Organization addressed additional comments from the public to complete the document. The final document was The Writing Committee was selected to represent the approved by the Task Force, COCATS Steering Com- American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the Amer- mittee, and ACC Competency Management Commit- ican Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) and tee; ratified by the ACC Board of Trustees in March, included a cardiovascular training program director; a 2015; and endorsed by the ASNC. This document is nuclear cardiology training program director; early- considered current until the ACC Competency Man- career experts; highly experienced specialists in agement Committee revises or withdraws it. both academic and community-based practice set- tings; and physicians experienced in defining and applying training standards according to the 6 general 1.2. Background and Scope competency domains promulgated by the Accredita- Nuclear cardiology provides important diagnostic and tion Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) prognostic information that is an essential part of the and American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), knowledge base required of the well-trained cardiol- and endorsed by the American Board of Internal ogist for optimal management of the cardiovascular Medicine (ABIM). -

Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Training in Internal Medicine Residents

Clinical AND Health Affairs Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Training in Internal Medicine Residents BY MOLLIE ALPERN, MD, QI WANG, MS, AND MEGHAN ROTHENBERGER, MD Common allergic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, asthma and antibiotic allergies are frequently encountered by internal medicine physicians. These conditions are a significant source of health care utilization and morbidity. However, many internal medicine residency programs offer limited training in allergy and immunology. Internal medicine residents’ significant knowledge deficits regarding allergy-related content have been previously identified. We conducted a survey-based study to examine the knowledge and self-assessed clinical competency of residents at an academic medical center to determine the need for further education in allergy and immunology. Our study revealed that the majority of these residents did not feel adequately prepared to treat allergic rhinitis, urticaria, contact dermatitis, antibiotic/drug allergies or anaphylaxis; and only half felt adequately trained to treat asthma. We believe that internal medicine residency programs should provide trainees with additional education in allergy and immunology in order to improve their knowledge and clinical competency. COMMENTARY: DON’T BLOW OFF AR Physicians should help patients with the Rodney Dangerfield of respiratory diseases. BY BARBARA P. YAWN, MD, MSC, FAAFP 6,7 The above article, “Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Training average, greater than that for diabetes. The very common in Internal Medicine Residents,” shines a light on an interesting symptom of nasal congestion affects sleep in people of all issue: Many primary care physicians feel unprepared to address ages, and in children has been shown to interfere with school 8 some of the most common respiratory concerns of patients. -

Essentials of Cardiology Timothy C

Th e Heart SECTION IV Essentials of Cardiology Timothy C. Slesnick, Ralph Gertler, and CHAPTER 14 Wanda C. Miller-Hance Congenital Heart Disease Evaluation of the Patient with a Cardiac Murmur Incidence Basic Interpretation of the Pediatric Segmental Approach to Diagnosis Electrocardiogram Physiologic Classifi cation of Defects Essentials of Cardiac Rhythm Interpretation and Acute Arrhythmia Management in Children Acquired Heart Disease Basic Rhythms Cardiomyopathies Conduction Disorders Myocarditis Cardiac Arrhythmias Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease Pacemaker Therapy in the Pediatric Age Group Infective Endocarditis Pacemaker Nomenclature Kawasaki Disease Permanent Cardiac Pacing Cardiac Tumors Diagnostic Modalities in Pediatric Cardiology Heart Failure in Children Chest Radiography Defi nition and Pathophysiology Barium Swallow Etiology and Clinical Features Echocardiography Treatment Strategies Magnetic Resonance Imaging Syndromes, Associations, and Systemic Disorders: Cardiovascular Disease and Anesthetic Implications Computed Tomography Chromosomal Syndromes Cardiac Catheterization and Angiography Gene Deletion Syndromes Considerations in the Perioperative Care of Children with Cardiovascular Disease Single-Gene Defects General Issues Associations Clinical Condition and Status of Prior Repair Other Disorders Summary Selected Vascular Anomalies and Their Implications for Anesthetic Care Aberrant Subclavian Arteries Persistent Left Superior Vena Cava to Coronary Sinus Communication Congenital Heart Disease adulthood has become the expectation for most congenital car- diovascular malformations.3 At present it is estimated that there Incidence are more than a million adults with CHD in the United States, Estimates of the incidence of congenital heart disease (CHD) surpassing the number of children similarly aff ected for the fi rst range from 0.3% to 1.2% in live neonates.1 Th is represents the time in history. -

Bed-Based Ballistocardiography: Dataset and Ability to Track Cardiovascular Parameters

sensors Article Bed-Based Ballistocardiography: Dataset and Ability to Track Cardiovascular Parameters Charles Carlson 1,* , Vanessa-Rose Turpin 2, Ahmad Suliman 1 , Carl Ade 2, Steve Warren 1 and David E. Thompson 1 1 Mike Wiegers Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (D.E.T.) 2 Department of Kinesiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA; [email protected] (V.-R.T.); [email protected] (C.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Background: The goal of this work was to create a sharable dataset of heart-driven signals, including ballistocardiograms (BCGs) and time-aligned electrocardiograms (ECGs), photoplethysmo- grams (PPGs), and blood pressure waveforms. Methods: A custom, bed-based ballistocardiographic system is described in detail. Affiliated cardiopulmonary signals are acquired using a GE Datex CardioCap 5 patient monitor (which collects ECG and PPG data) and a Finapres Medical Systems Finometer PRO (which provides continuous reconstructed brachial artery pressure waveforms and derived cardiovascular parameters). Results: Data were collected from 40 participants, 4 of whom had been or were currently diagnosed with a heart condition at the time they enrolled in the study. An investigation revealed that features extracted from a BCG could be used to track changes in systolic blood pressure (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.54 +/− 0.15), dP/dtmax (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.51 +/− 0.18), and stroke volume (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.54 +/− 0.17). Conclusion: A collection of synchronized, heart-driven signals, including BCGs, ECGs, PPGs, and blood pressure waveforms, was acquired and made publicly available. -

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Compact ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Core Tenets of Residency ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Program Requirements ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Resident Recruitment/Appointments .............................................................................................. 9 Background Check Policy ................................................................................................................ 10 New Innovations ............................................................................................................................. 11 Social Networking Guidelines ......................................................................................................... 11 Dress Code ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Resident’s Well Being ...................................................................................................................... 13 Academic Conference Attendance ................................................................................................ -

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (As of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (as of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee Program Specialty Requirement(s) Requirements for PGY-1 Anesthesiology III.A.2.a).(1); • Residents must have successfully completed 12 months of IV.C.3.-IV.C.3.b); education in fundamental clinical skills in a program accredited by IV.C.4. the ACGME, the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC), or the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), or in a program with ACGME International (ACGME-I) Advanced Specialty Accreditation. • 12 months of education must provide education in fundamental clinical skills of medicine relevant to anesthesiology o This education does not need to be in first year, but it must be completed before starting the final year. o This education must include at least six months of fundamental clinical skills education caring for inpatients in family medicine, internal medicine, neurology, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, surgery or any surgical specialties, or any combination of these. • During the first 12 months, there must be at least one month (not more than two) each of critical care medicine and emergency medicine. Dermatology III.A.2.a).(1)- • Prior to appointment, residents must have successfully completed a III.A.2.a).(1).(a) broad-based clinical year (PGY-1) in an emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, or a transitional year program accredited by the ACGME, AOA, RCPSC, CFPC, or ACGME-I (Advanced Specialty Accreditation). • During the first year (PGY-1), elective rotations in dermatology must not exceed a total of two months. -

Internal Medicine Interest Group Resource Guide

Making the Most of Your Internal Medicine Interest Group: A Practical Resource Guide Developed by the Council of Student Members June 2015 EX4038 Table of Contents Introduction to Internal Medicine Interest Groups................................................................................1 Establishing an IMIG at your School........................................................................................................1 Best Practices for IMIGs ............................................................................................................................3 Holding an Internal Medicine Residency Fair ........................................................................................8 Appendix....................................................................................................................................................9 Introduction to Internal Establishing an IMIG at Your School Medicine Interest Groups You should seek advice from as many resources as possible during the planning An internal medicine interest group (IMIG) is stages. Be sure to consult with your school’s an organized group of medical students who administration about how to establish an meet regularly to learn about internal medi- official club at your school. Once the group’s cine and to establish communication with leadership is established, an e-mail should be faculty and other students who share similar sent out to all group members to poll them interests. IMIGs have a faculty advisor who about activities in which they -

Cocats 4 (Pdf)

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY VOL. 65, NO. 17, 2015 ª 2015 BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATION ISSN 0735-1097/$36.00 PUBLISHED BY ELSEVIER INC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.017 TRAINING STATEMENT ACC 2015 Core Cardiovascular Training Statement (COCATS 4) (Revision of COCATS 3) A Report of the ACC Competency Management Committee Task Force Introduction/Steering Committee Task Force 3: Training in Electrocardiography, Members Jonathan L. Halperin, MD, FACC Ambulatory Electrocardiography, and Exercise Testing (and Society Eric S. Williams, MD, MACC Gary J. Balady, MD, FACC, Chair Representation) Valentin Fuster, MD, PHD, MACC Vincent J. Bufalino, MD, FACC Martha Gulati, MD, MS, FACC Task Force 1: Training in Ambulatory, Jeffrey T. Kuvin, MD, FACC Consultative, and Longitudinal Cardiovascular Care Lisa A. Mendes, MD, FACC Valentin Fuster, MD, PHD, MACC, Co-Chair Joseph L. Schuller, MD Jonathan L. Halperin, MD, FACC, Co-Chair Eric S. Williams, MD, MACC, Co-Chair Task Force 4: Training in Multimodality Imaging Nancy R. Cho, MD, FACC Jagat Narula, MD, PHD, MACC, Chair William F. Iobst, MD* Y.S. Chandrashekhar, MD, FACC Debabrata Mukherjee, MD, FACC Vasken Dilsizian, MD, FACC Prashant Vaishnava, MD Mario J. Garcia, MD, FACC Christopher M. Kramer, MD, FACC Task Force 2: Training in Preventive Shaista Malik, MD, PHD, FACC Cardiovascular Medicine Thomas Ryan, MD, FACC Sidney C. Smith, JR, MD, FACC, Chair Soma Sen, MBBS, FACC Vera Bittner, MD, FACC Joseph C. Wu, MD, PHD, FACC J. Michael Gaziano, MD, FACC John C. Giacomini, MD, FACC Quinn R. Pack, MD Donna M.