Assignment 1: Case Study Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Bash League 2018-19 Fixtures

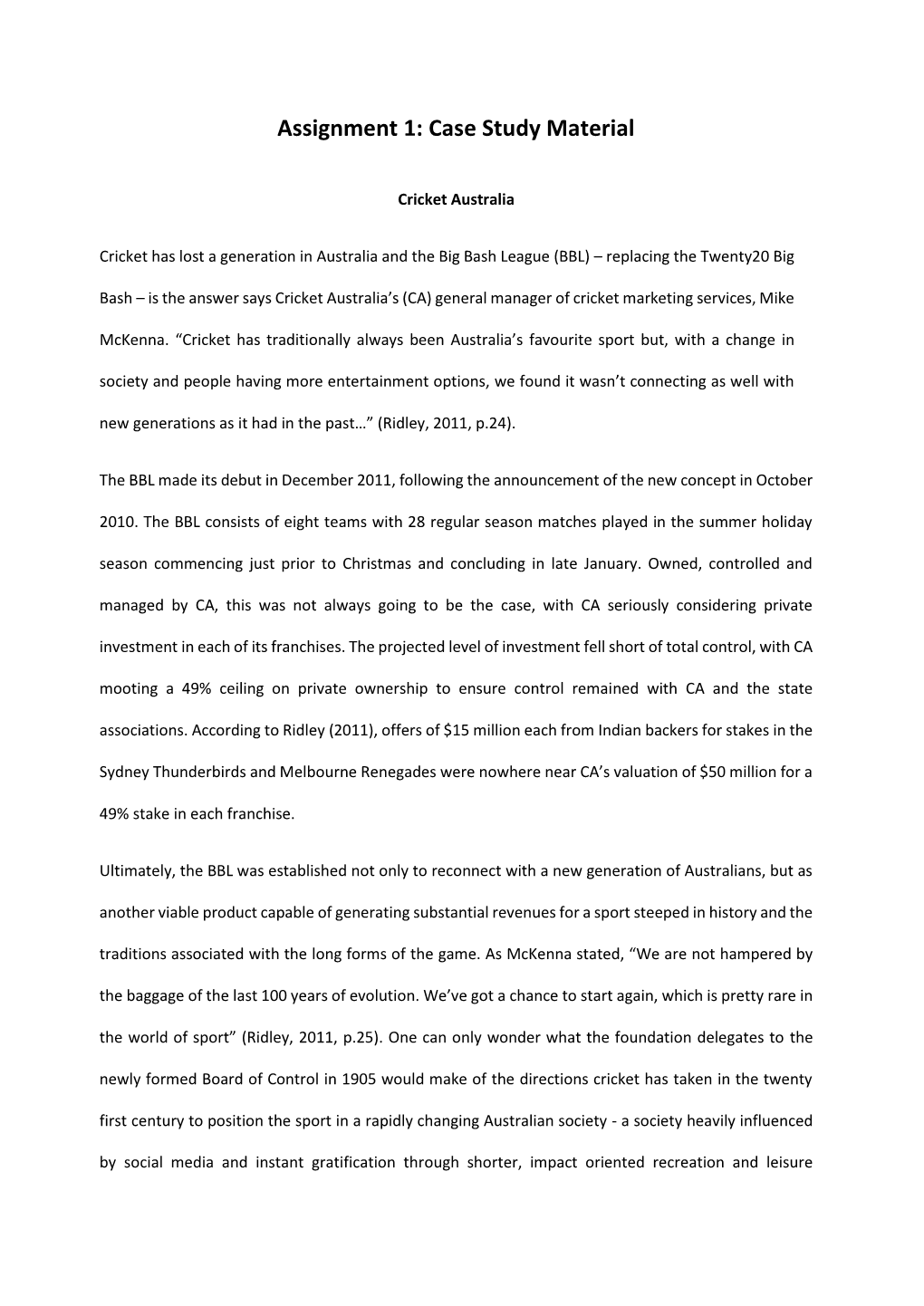

Big Bash League 2018-19 Fixtures DATE TIME MATCH FIXTURE VENUE 19 December 18:15 Match 1 Brisbane Heat v Adelaide Strikers The Gabba 20 December 19:15 Match 2 Melbourne Renegades v Perth Scorchers Marvel Stadium 21 December 19:15 Match 3 Sydney Thunder v Melbourne Stars TBD 22 December 15:30 Match 4 Sydney Sixers v Perth Scorchers SCG 18:00 Match 5 Brisbane Heat v Hobart Hurricanes Carrara Stadium 23 December 18:45 Match 6 Adelaide Strikers v Melbourne Renegades Adelaide Oval 24 December 15:45 Match 7 Hobart Hurricanes v Melbourne Stars Bellerive Oval 19:15 Match 8 Sydney Thunder v Sydney Sixers Spotless Stadium 26 December 16:15 Match 9 Perth Scorchers v Adelaide Strikers Optus Stadium 27 December 19:15 Match 10 Sydney Sixers v Melbourne Stars SCG 28 December 19:15 Match 11 Hobart Hurricanes v Sydney Thunder Bellerive Oval 29 December 19:00 Match 12 Melbourne Renegades v Sydney Sixers Docklands 30 December 19:15 Match 13 Hobart Hurricanes v Perth Scorchers York Park 31 December 18:15 Match 14 Adelaide Strikers v Sydney Thunder Adelaide Oval 1 January 13:45 Match 15 Brisbane Heat v Sydney Sixers Carrara Stadium 19:15 Match 16 Melbourne Stars v Melbourne Renegades MCG 2 January 19:15 Match 17 Sydney Thunder v Perth Scorchers Spotless Stadium 3 January 19:15 Match 18 Melbourne Renegades v Adelaide Strikers TBC 4 January 19:15 Match 19 Hobart Hurricanes v Sydney Sixers Bellerive Oval 5 January 17:15 Match 20 Melbourne Stars v Sydney Thunder Carrara Stadium 18:30 Match 21 Perth Scorchers v Brisbane Heat Optus Stadium 6 January 18:45 Match -

Cricket Australia

Submission 035 Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs: Inquiry into the contribution of sport to Indigenous wellbeing and mentoring November 2012 1 Submission 035 Contents Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 Background ................................................................................................................................ 4 Australian Cricket Initiatives ...................................................................................................... 5 The future of Australian Cricket ................................................................................................. 8 Outcomes ................................................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................. 9 2 | Page 2 Submission 035 Purpose This submission seeks to inform the Committee of the work that Cricket Australia (CA) does in Indigenous communities, delivering opportunities in cricket for Indigenous men and women across Australia, and the positive impacts on Indigenous wellbeing as a result. This submission analyses what more can -

Ow, Look Out! They’Re out There Again

Palm Island Voice Your Community Issue 47 Your Newsletter Tuesday 17 November 2009 Your Voice Ow, look out! They’re out there again... The Stinger Season has arrived with one person from Palm Island already confirmed as stung by one of the marine creatures. It’s a timely reminder that prevention is better than cure, says paramedic Ian Day. The young person concerned had her stinger suit purchased for her the week before, but wasn’t wearing it at the time of the attack. After a painful night in hospital she told the Palm Island Voice she wouldn’t be going into the water again without it. QAS Palm Island has just taken delivery of this year’s supply of stinger suits and for the first time now cater for all ages and all sizes from size 2 child to size 28 adult. Mr Day said some sizes were limited and sales would be on a “first in, first served’ basis. He also said they could not take book-ups, only cash. Condolence message from Brigadier Stuart Smith The most senior “In life, Bill was greatly League match between the Army officer in north admired by our Army for Palm Island Skipjacks and Queensland has sent an three reasons,” he said. Lavarack Barracks Army as exclusive message “First, he was an the Coolburra Shield event. of condolence to the accomplished soldier. “Lastly, and most Palm Island Voice to “Indeed, he had proven importantly, he was a mark the passing of his bravery as a combat mentor. He encouraged “greatly admired” elder engineer with the 3rd Field young people to consider Bill Coolburra. -

Cricket Tasmania Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019-20

Chairman’s Report 2 Chief Executive’s Report 4 Financial Statements 6 Partners 28 Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 30 June 2020 as presented at the Annual General Meeting of the Association on 21 September 2020. Image credits: Alastair Bett and Richard Jupe/The Mercury Normally the Chairman’s Report focuses on the season end of the season and was a chance to make the just past and the season forthcoming. Of course, for all Sheffield Shield final, before the last round of matches sport the emergence of Covid-19 has resulted in a was cancelled. Our men’s Hurricanes team made the huge disruption. As I write this in mid-September the finals for the third year in a row but unfortunately ran fixture for 2020/21 remains unclear. We continue to into an in-form Sydney Thunder outfit at Blundstone live in Arena. Big Bash silverware has remained elusive for uncertain sporting times and the best that we can do at our teams and it would be nice to see a trophy in the Cricket Tasmania is “prepare for the worst, hope for cabinet at Blundstone Arena. the best”. Luckily we entered the pandemic in sound The Tasmanian Tigers Women’s side had a frustrating financial shape. A number of years of strong results WNCL season with two wins out of their eight matches. had seen Cricket Tasmania’s debt reduced from $5.3 The highlight of the competition was in January with million to $2 million. Selling the Hurricanes match into back-to-back victories over the SA Scorpions in Alice Springs was financially lucrative and Cricket Adelaide Tasmania had increased revenues from the Function There were numerous notable performances Centre, sponsorship and through Government grants. -

Cricket Australia Junior Formats

CRICKET AUSTRALIA APRIL JUNIOR CRICKET POLICY 2004 CRICKET AUSTRALIA JUNIOR CRICKET POLICY 1 Table of Contents 1.0 Everyone Can Play: Fostering Equity of Access and Enjoyment of Cricket • Fun in Cricket • Girls’ Participation • Benefits of Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents 2.0 The Cricket Pathway: Player Development and Game Formats • Children’s Development in Sport • Nurturing our Young Cricketers’ Skills • Snapshot of Skill and Game Progressions for Club and School Cricket • Social and Participative Cricket • Representative Cricket 3.0 Safety Guidelines: Strategies to Promote Safety and Prevent Injuries • Injury Prevention • Bowling Guidelines and Restrictions • Helmets, Field Placements, Ground and Weather Conditions Introduction • Guidelines for Heat, Hydration and Sun Protection 4.0 Strategies for Managing and Growing Enhancing the Junior Cricket Clubs • Player Recruitment Cricket experience • Player Retention • Implementing Junior Cricket Guidelines and Welcome Administrators, Coaches, Procedures Teachers & Parents • Make cricket fun for • Cricket Australia Modified Cricket Programs t is my pleasure to introduce you to the Cricket everyone; system. As the custodians 5.0 Spirit and Etiquette of the Game: Australia Junior Cricket Policy. The purpose of the • Develop safety guidelines and responsible for the future of the The Unwritten Laws of Cricket IJunior Cricket Policy is to provide a framework for all principles to prevent injuries; game of cricket, we must be • Spirit of Cricket those involved in the game at junior level and to allow • Foster the spirit of cricket and committed to ensuring others • Cricket Etiquette for a consistent, safe, and nurturing environment for all etiquette of the game; enjoy the rewards of life-long cricket involvement. -

05. T He Sheffield Shield

05 05. THE SHEFFIELD SHIELD Playing Conditions | 2014-15 27 05 05. THE SHEFFIELD SHIELD 28 Playing Conditions | 2014-15 2014-15 SHEFFIELD SHIELD Match Start Date End Date Home Team Vs Away Team Venue Local Start Friday, October 31, Monday, November WESTERN 1 v TASMANIA WACA 10:30 am 2014 03, 2014 AUSTRALIA Friday, October 31, Monday, November NEW SOUTH 2 VICTORIA v MCG 10:30 am 2014 03, 2014 WALES Friday, October 31, Monday, November SOUTH 3 v QUEENSLAND ADELAIDE OVAL 10:30 am 2014 03, 2014 AUSTRALIA Saturday, November Tuesday, November WESTERN 4 v QUEENSLAND WACA 1:30 pm 08, 2014 11, 2014 AUSTRALIA Saturday, November Tuesday, November BLUNDSTONE 5 TASMANIA v VICTORIA 2:00 pm 08, 2014 11, 2014 ARENA Saturday, November Tuesday, November SOUTH NEW SOUTH 6 v ADELAIDE OVAL 2:00 pm 08, 2014 11, 2014 AUSTRALIA WALES Sunday, November Wednesday, NEW SOUTH 7 QUEENSLAND v GABBA 10:00 am 16, 2014 November 19, 2014 WALES Sunday, November Wednesday, WESTERN BLUNDSTONE 8 TASMANIA v 10:30 am 16, 2014 November 19, 2014 AUSTRALIA ARENA Sunday, November Wednesday, SOUTH 9 v VICTORIA ADELAIDE OVAL 10:30 am 16, 2014 November 19, 2014 AUSTRALIA Tuesday, November Friday, November 28, NEW SOUTH SOUTH 10 v SCG 10:30 am 25, 2014 2014 WALES AUSTRALIA 29 Playing Conditions | 2014-15 THE SHEFFIELD SHIELD SHEFFIELD THE 05. 05. 30 05. THE SHEFFIELD SHIELD Match Start Date End Date Home Team Vs Away Team Venue Local Start Tuesday, November Friday, November 28, 11 QUEENSLAND v TASMANIA AB FIELD 10:00 am 25, 2014 2014 Tuesday, November Friday, November 28, WESTERN 12 -

International Cricket Council

TMUN INTERNATIONAL CRICKET COUNCIL FEBRUARY 2019 COMITTEEE DIRECTOR VICE DIRECTORS MODERATOR MRUDUL TUMMALA AADAM DADHIWALA INAARA LATIFF IAN MCAULIFFE TMUN INTERNATIONAL CRICKET COUNCIL A Letter from Your Director 2 Background 3 Topic A: Cricket World Cup 2027 4 Qualification 5 Hosting 5 In This Committee 6 United Arab Emirates 7 Singapore and Malaysia 9 Canada, USA, and West Indies 10 Questions to Consider 13 Topic B: Growth of the Game 14 Introduction 14 Management of T20 Tournaments Globally 15 International Tournaments 17 Growing The Role of Associate Members 18 Aid to Troubled Boards 21 Questions to Consider 24 Topic C: Growing Women’s Cricket 25 Introduction 25 Expanding Women’s T20 Globally 27 Grassroots Development Commitment 29 Investing in More Female Umpires and Match Officials 32 Tying it All Together 34 Questions to Consider 35 Advice for Research and Preparation 36 Topic A Key Resources 37 Topic B Key Resources 37 Topic C Key Resources 37 Bibliography 38 Topic A 38 Topic B 40 Topic C 41 1 TMUN INTERNATIONAL CRICKET COUNCIL A LETTER FROM YOUR DIRECTOR Dear Delegates, The International Cricket Council (ICC) is the governing body of cricket, the second most popular sport worldwide. Much like the UN, the ICC brings representatives from all cricket-playing countries together to make administrative decisions about the future of cricket. Unlike the UN, however, not all countries have an equal input; the ICC decides which members are worthy of “Test” status (Full Members), and which are not (Associate Members). While the Council has experienced many successes, including hosting the prestigious World Cup and promoting cricket at a grassroots level, it also continues to receive its fair share of criticism, predominantly regarding the ICC’s perceived obstruction of the growth of the game within non- traditionally cricketing nations and prioritizing the commercialization of the sport over globalizing it. -

Exploring Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Inclusion in Australian Cricket

Exploring Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Inclusion in Australian Cricket Dr Ryan Storr Dr Grant O’Sullivan Associate Professor Caroline Symons Professor Ramón Spaaij Melissa Sbaraglia August 2017 Prepared for Cricket Australia & Cricket Victoria August 2017 Victoria University, August 2017 1 Acknowledgements The preparation of this research report has been a collaborative effort between Cricket Victoria, Cricket Australia and the Institute of Sport, Exercise and Active Living (ISEAL), Victoria University. We also acknowledge the support of the Victorian State Government and Sport and Recreation Victoria in supporting this research. This support has contributed to a leading piece of research from a State Government and State Sport Organisation within the area of LGBT inclusion in sport. Appreciation to the following: Cricket Victoria: Emma Staples Cricket Australia: Sam Almaliki Copyright This report has been prepared by ISEAL on behalf of Cricket Victoria and Cricket Australia. The information contained in this report is intended for specific use by Cricket Victoria and Cricket Australia and may not be used by any other organisation for any other project without the permission of ISEAL. All recommendations identified by ISEAL are based on information provided by Cricket Victoria and Cricket Australia with input from staff, community participants and players. ISEAL has relied on this information to be correct at the time this report was prepared. © Copyright 2017 to ISEAL Contact details For further information regarding this research project, please contact: Professor Ramón Spaaij Research Focus Leader (Sport for Inclusive Communities) Institute of Sport, Exercise and Active Living Victoria University PO Box 14428, Melbourne VIC 8001 E: [email protected] T: 03 9919 4683 Victoria University, August 2017 2 Exploring LGBT Inclusion in Australian Cricket Table of Contents List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... -

Issue 40: Summer 2009/10

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 40, Summer 2009 This Issue From our Summer 2009/10 edition Ken Williams looks at the fi rst Pakistan tour of Australia, 45 years ago. We also pay tribute to Richie Benaud's role in cricket, as he undertakes his last Test series of ball-by-ball commentary and wish him luck in his future endeavours in the cricket media. Ross Perry presents an analysis of Australia's fi rst 16-Test winning streak from October 1999 to March 2001. A future issue of The Yorker will cover their second run of 16 Test victories. We note that part two of Trevor Ruddell's article detailing the development of the rules of Australian football has been delayed until our next issue, which is due around Easter 2010. THE EDITORS Treasures from the Collections The day Don Bradman met his match in Frank Thorn On Saturday, February 25, 1939 a large crowd gathered in the Melbourne District competition throughout the at the Adelaide Oval for the second day’s play in the fi nal 1930s, during which time he captured 266 wickets at 20.20. Sheffi eld Shield match of the season, between South Despite his impressive club record, he played only seven Australia and Victoria. The fans came more in anticipation games for Victoria, in which he captured 24 wickets at an of witnessing the setting of a world record than in support average of 26.83. Remarkably, the two matches in which of the home side, which began the game one point ahead he dismissed Bradman were his only Shield appearances, of its opponent on the Shield table. -

Media Release 13 November 2015

Media Release 13 November 2015 VicHealth announced as first major partner for Melbourne’s two Women’s Big Bash League teams The Melbourne Stars and Melbourne Renegades today (13 November) announced VicHealth as the first major partner for both clubs’ Women’s Big Bash League (WBBL) cricket teams ahead of the inaugural season, which begins next month. In a major boost for both clubs, the partnership was created through VicHealth’s Changing the Game: Increasing Female Participation in Sport program which aims to increase the number of women and girls who are physically active, raise the profile of women’s sport in the media and championing the important role women play in sports’ leadership and management. As part of the partnership, the Stars and Renegades will play for the Lanning Elliott Cup at the WBBL derby at the MCG on 2 January 2016. VicHealth CEO Jerril Rechter described the partnership as a major step towards raising the profile of women’s sport and championing the important role women play in decision making and leadership roles. “We want to change attitudes and change the game. Partnering with the Melbourne Stars and the Melbourne Renegades to support the first Women’s Big Bash League season is a major step in ensuring that women’s sport gets the recognition it deserves.” “This has been an amazing year for women’s sport in Australia. We’ve got some of the best female athletes on the planet, and they deserve better recognition. Recent VicHealth research shows that 62 per cent of Victorians think women’s sport should get more coverage in the media. -

Sports Calendar

SPORTS CALENDAR Tuesday 1st Big Bash: Brisbane Heat vs Sixers 3pm - 7:15pm Friday 18th Melbourne Stars vs Melbourne Renegades NBA: 76ers vs Pacers - Lakers vs Thunder 11pm - 1:30pm A League: Western Sydney vs Melbourne City 8pm Cricket: Australia vs India 3rd ODI 1:30pm Big Bash: Perth Scorchers vs Hobart Hurricanes 9:30pm Wednesday 2nd A League: Western Sydney vs Adelaide 8pm Big Bash: Sydney Thunder vs Perth Scorchers 7:15 pm A League: Newcastle vs Brisbane 8pm Saturday 19th Thursday 3rd NBA: Spurs vs T’Wolves - Pelicans vs T’Blazers 12pm - 2:30pm Big Bash: Melbourne Renegades vs Melbourne Stars 7pm NBA: T’Wolves vs Celtics - Thunder Vs Lakers 12pm - 2pm A League: Sydney vs Newcastle Cricket: Australia vs India 4th Test 10:30 am Melbourne City vs Perth 5:30pm - 8pm Big Bash: Melbourne Renegades vs Adelaide Strikers 7:15 pm Friday 4th Sunday 20th NBA: Raptors vs Spurs - Rockets vs Warriors 12pm - 2:30pm NBA: Lakers vs Rockets 12:30 pm Cricket: Australia vs India 4th Test 10:30 am UFC Fight Night 1pm Big Bash: Hobart Hurricanes vs Sydney Sixers 7:15 pm Big Bash: Sydney Sixers vs Brisbane Heat 7:30pm A League: Sydney vs Central Coast 8pm A League: Melbourne Victory vs Wellington 5pm - 7pm Central Coast vs Brisbane Saturday 5th NBA: Wizards vs Heat - Thunder vs T’Blazers 12pm - 2:30pm Monday 21st Cricket: Australia vs India 4th Test 10:30 am Big Bash: Adelaide Strikers vs Hobart Hurricanes 7:30pm Big Bash: Melbourne Stars vs Sydney Thunder 7pm - 9:30pm Perth Scorchers vs Brisbane Heat Tuesday 22nd A League: Adelaide vs Wellington 6pm - -

Strategic Plan 2017-2022 QC STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2022

Strategic Plan 2017-2022 QC STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2022 VISION PURPOSE VALUES To be Queensland’s To unite and inspire Be Real, Clear the Favourite Sport Queensland communities Boundaries, Make Every Ball through cricket Count, Stronger Together STRATEGIC AMBITION SECURING CRICKET’S FUTURE IN QUEENSLAND Cricket participation in Queensland continues to grow, has improved facilities and is providing great experiences. No matter where you live, no matter your background, gender or ability, anyone can have their say, anyone can have a go, anyone can enjoy the game, anyone can achieve their cricket dreams. Queensland Cricket will have built the financial security to support these aspirations – no matter how big or small. STRATEGIC GOALS GROW PARTICIPATION BETTER PLAYERS AND TEAMS GROW AND ENGAGE FANS Grow the level of interest and sustainable Identify, develop and produce great Grow the love of cricket through participation in cricket across all cricketers and successful teams, and even outstanding fan experiences based on demographics and communities better people. world class entertainment, engagement throughout Queensland. and communications. FOCUS AREAS CLUBS AND INFRASTRUCTURE ORGANISATIONAL FINANCIAL VOLUNTEERS AND FACILITIES EFFECTIVENESS PARTNERSHIPS SUSTAINABILITY Empower and support Build the right facilities Build a proactive, authentic Develop and enhance Secure the financial future volunteers and clubs to at the right locations to and future focussed our relationships with all of cricket in Queensland to sustainably grow the game improve the quality and organisation to lead the partners for mutual benefit. fund our ambitions. in Queensland. experience for participants cricket community in and fans. Queensland. MUST ACHIEVES 2019/2020 1. 2. 3. 4.