Branches on the Oldest Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November/December 2004 Newsletter

The Retreat Newsletter November/December 2004 Volume 1, Issue 4 FRANCES FUELS FRIENDSHIPS September 4, 2004 By Hank Stasiewicz As we sat and listened, from storm tall, a symbol of community pride and along their way, they created new paneled concrete “bunkers,” to the unity. friendships, some of which will last wind howling at unbelievable decibels, What developed in those days and, unfortunately, some will not. for what seemed an eternity, we could preceding Frances was a If you asked them, “Why do only wonder what unpredictable you do this?” I am sure feeling of camaraderie “What developed in those disasters Hurricane Frances had in the reply would be a between neighbors, days preceding Frances was store for the residents of The Retreat some of which had a feeling of camaraderie resounding and Florida. Many residents chose to never met each other between neighbors, some of “Because we care!” protect their homes and travel to a formally. A feeling of which had never met each Items in need were safer area, but for those who chose to need and a feeling of other formally.” readily shared with stay within the confines of their homes, giving permeated the air. those who required an unexpected blessing would enter We found ourselves working side them. Those of us that are many of their lives. by side, hungry, tired and sweaty, to seasoned storm survivors guided In the time preceding Frances, in a help our neighbors, to protect our lives, the novices. Our prior hurricane period filled with anxious preparations, homes and assets. Residents, informally knowledge was freely given, and an unusual, but not unheard of, series assembled into loose groups, traversed gratefully accepted, by those who had of events unfolded. -

The Construction of Adversarial Growth in the Wake of a Hurricane

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Construction of Adversarial Growth in the Wake of a Hurricane Beverly Lynn Mcclay Borawski University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Mcclay Borawski, Beverly Lynn, "The Construction of Adversarial Growth in the Wake of a Hurricane" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3241 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Construction of Adversarial Growth in the Wake of a Hurricane by Beverly L. McClay Borawski A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Communication College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor, Kenneth N. Cissna, Ph.D. Carolyn Ellis, Ph.D. Jane Jorgenson, Ph.D. Graham A. Tobin, Ph.D. Date of Approval March 29, 2011 Keywords: Coping, Emotional Support, Interpersonal Communication, Natural Disasters, Recovery Copyright © 2011, Beverly L. McClay Borawski DEDICATION To Dr. Kenneth N. Cissna, my committee chair, advisor, professor, and friend, thank you for your unflagging support, encouragement, insight, and advice. The countless hours you have devoted to providing me with useful feedback have been sustaining and inspiring. To Drs. Carolyn Ellis, Jane Jorgenson, and Graham A. -

Somebody Told Me You Died

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2020 Somebody Told Me You Died Barry E. Maxwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Nonfiction Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maxwell, Barry E., "Somebody Told Me You Died" (2020). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11606. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11606 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOMEBODY TOLD ME YOU DIED By BARRY EUGENE MAXWELL Associate of Arts in Creative Writing, Austin Community College, Austin, TX, 2015 Bachelor of Arts with Honors, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, 2017 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Nonfiction The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2020 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg Dean of The Graduate School Judy Blunt Director, Creative Writing Department of English Kathleen Kane Department of English Mary-Ann Bowman Department of Social Work Maxwell, Barry, Master of Fine Arts, Spring 2020 Creative Writing, Nonfiction Somebody Told Me You Died Chairperson: Judy Blunt Somebody Told Me You Died is a sampling of works exploring the author’s transition from “normal” life to homelessness, his adaptations to that world and its ways, and his eventual efforts to return from it. -

Party in the Usa Sheet Music

Party In The Usa Sheet Music Download party in the usa sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 3 pages partial preview of party in the usa sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2641 times and last read at 2021-09-24 09:12:18. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of party in the usa you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: A Cappella, Alto Voice, Bass Voice, Soprano Voice, Tenor Voice Ensemble: 4 Part, A Cappella, Satb Level: Early Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Party Time Party Time sheet music has been read 5006 times. Party time arrangement is for Beginning level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 14:27:30. [ Read More ] Crashing My Party Crashing My Party sheet music has been read 2993 times. Crashing my party arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 21:08:09. [ Read More ] Valentine Party Valentine Party sheet music has been read 3917 times. Valentine party arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 18:25:29. [ Read More ] When The Party Over Woodwind Trio When The Party Over Woodwind Trio sheet music has been read 2113 times. When the party over woodwind trio arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-25 23:18:27. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

“Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans?” the Use of Popular Music After Hurricane Katrina

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE August 2016 “Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans?” The use of popular music after Hurricane Katrina Jennifer Billinson Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Billinson, Jennifer, "“Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans?” The use of popular music after Hurricane Katrina" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 650. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/650 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This single-case study explores the use of popular music in response to the destruction of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina in August, 2005. Using research in sociology of disaster and uses and gratifications theory in mass communication, data collected included original music written in response to the hurricane, major benefit concerts that aired in the wake, and re-appropriated music that developed new meaning when used in conjunction to the case. Analysis yielded that popular music was used to raise awareness, raise funds, and express emotion following the disaster. Common themes throughout include the impact of genre on how this was accomplished and the messages it yielded, the power of collective effervescence, and the importance of space and place when dealing with tragedy through music. ‘DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS?’ THE USE OF POPULAR MUSIC AFTER HURRICANE KATRINA by Jennifer Billinson B.A., Indiana University, 2006 M.A., Syracuse University, 2009 Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mass Communications Syracuse University August 2016 Copyright © Jennifer Billinson 2016 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction p. -

Nominations List

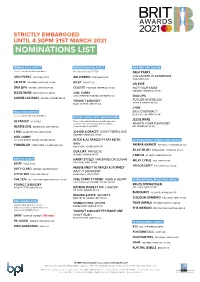

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 4.30PM 31ST MARCH 2021 NOMINATIONS LIST FEMALE SOLO ARTIST BREAKTHROUGH ARTIST MASTERCARD ALBUM In association with Amazon Music In association with TikTok ARLO PARKS ARLO PARKS TRANSGRESSIVE ARLO PARKS TRANSGRESSIVE COLLAPSED IN SUNBEAMS TRANSGRESSIVE CELESTE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC BICEP NINJA TUNE CELESTE DUA LIPA WARNER, WARNER MUSIC CELESTE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC NOT YOUR MUSE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JESSIE WARE EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JOEL CORRY ASYLUM/PERFECT HAVOC, WARNER MUSIC DUA LIPA LIANNE LA HAVAS WARNER, WARNER MUSIC YOUNG T & BUGSEY FUTURE NOSTALGIA WARNER, WARNER MUSIC BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC J HUS MALE SOLO ARTIST BIG CONSPIRACY BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC In association with Amazon Music BRITISH SINGLE WITH MASTERCARD JESSIE WARE AJ TRACEY AJ TRACEY The top ten identified by chart eligible sales success then voted for by The Academy, WHAT'S YOUR PLEASURE? HEADIE ONE RELENTLESS, SONY MUSIC Supported by Capital FM EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC J HUS BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC 220 KID & GRACEY DON'T NEED LOVE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JOEL CORRY ASYLUM/PERFECT HAVOC, WARNER MUSIC AITCH & AJ TRACEY FT TAY KEITH INTERNATIONAL FEMALE SOLO ARTIST RAIN YUNGBLUD INTERSCOPE, UNIVERSAL MUSIC ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC, UNIVERSAL MUSIC NQ, VIRGIN, UNIVERSAL MUSIC BILLIE EILISH INTERSCOPE, UNIVERSAL MUSIC DUA LIPA PHYSICAL WARNER, WARNER MUSIC CARDI B ATLANTIC, WARNER MUSIC BRITISH GROUP HARRY STYLES WATERMELON SUGAR MILEY CYRUS RCA, SONY MUSIC COLUMBIA, SONY MUSIC BICEP NINJA TUNE TAYLOR SWIFT EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC HEADIE -

Prisons and Floods in the United States Interrogating Notions of Social and Spatial Control

Prisons and Floods in the United States Interrogating Notions of Social and Spatial Control By Hannah Hauptman, Yale University On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina ripped across the state dream of full social order, both inside and outside Southern Louisiana, rupturing New Orleans’ levees and of the prison. Strict protocols, concrete beds, steel-barred scouring a place for itself among the costliest and most poorly windows and pacing guards imply that this dream has, managed disasters in contemporary history. On that fateful in fact, been realized. Yet foods, amongst other natural August morning, an inmate at the Orleans Parish Prison disasters, provide an avenue for chaos to move through the recalled, “we awake to fnd water up to our knees and no seemingly indestructible barriers of the prison. Troughout security.”1 Te water would eventually rise to the inmates’ the twentieth century and into the twenty-frst, foods have necks. As another inmate recounted, “it was like we were left threatened or necessitated emergency evacuations of prisons, to die. No water, no air, no food.”2 As the wealthy and the free as well as the movement of inmates out of prisons to work fed the city, inmates in local prisons—whose impregnable on food protection and rescue. Only by examining both the walls held frm while the once-impregnable levees crumbled— theoretical parallels and the historical convergences between were left locked in their cells. Hurricane Katrina brutally these two systems of control can we uncover their surprisingly illustrated the confict between the apparent order of prisons intimate relationship. Recovered narratives from fooded and the chaos of foods, revealing the diferentiated value of prisons, wherein the uncontrollable met the impenetrable, life placed on incarcerated individuals and troubling notions thus provide a historical nexus for the critical deconstruction of maximum security or absolute protection. -

Rod & Gun Gazette, September 2004

Fin Fur & Feather Club, Inc. September Volume 6, Issue 1 Charles Bruckerhoff Editor-in-Chief Matt Bruckerhoff Mike Bruckerhoff Copy Editors Rod & Gun Gazette Letter from the President As you all know, this will be my last letter, as my term as president is over. I would like to Inside this issue: thank all the officers , board members, committee chairmen and everyone who so gener- ously donated their time and efforts over the last three years to help make the Fin Fur & Feather Club the great club that it is today. In the last few years the club has grown consid- Election of Club Officers 2 erably with the new skeet and trap fields, sporting clays, 5 stand, the land purchase and also because of the tremendous responsibly that some members take upon themselves to organ- Return of Troop 34 2 ize and run committees like archery, the shooting sports, and the hunting and fishing sports. Also let’s not forget all the work that goes into the publishing of the newsletter, and how 2004 Hunting Rules & 4-5 much time is spent calculating the work hours, dues and assessments, the kitchen, and all Regulations the children’s activities. All these functions are done by members who are trying to keep the club moving in the right direction. I am very confident that our new officers and chairper- Pheasant Hunting Re- 6 sons will continue to do so as well. We are very fortunate to have these people; so let’s help quest Form them out not burn them out. -

Smash Hits Volume 50

OCTOBER 30 NOVEMBER 12 1980 tstti: TErrar5 HAZEL O'CONNOR AQAM & THE ANTS ORCHESTRAL MANOEUVRES & STATUS QUO IN COLOUR - ^gW^**^Oct. 30-Nov. 121980 Vol. 2 No. 22 THE TIDE IS HIGH Blondie 2 TOWERS OF LONDON XTC 5 DANCING WITH MYSELF Generation X S GENTLEMEN TAKE POLAROIDS Japan 8 ONE MAN WOMAN Sheena Easton 11 GIVE ME AN INCH Hazel O'Connor 18 LA-DI-DA Sad Cafe 21 IN MY STREET The Chords 24/25 LET ME TALK Earth Wind & Fire 27 I NEED YOUR LOVIN' Teena Marie 30 ALL OUT OF LOVE Air Supply 30 PASSING STRANGERS Ultravox 35 The Tide Is High HEROES The Stranglers 39 WHOSE PROBLEM Motels 42 Blondie FASHION David Bowie 51 on Chrysalis Records JAPAN: Feature 6/7/8 HAZEL O'CONNOR: Feature 16/17/18 STATUS QUO: Colour Poster 28/29 &KS2ES3S—-— ADAM & THE ANTS: Feature 40/41 O.M.I.T.D.: Colour Poster 52 BITZ 13/14/15 BIRO BUDDIES 22&34 CARTOON 22 MADNESS COMPETITION 24 DISCO 27 Repeat chorus CROSSWORD 31 REVIEWS 32/33 WHITESNAKE COMPETITION 34 rl antSVO,Jtob STAR TEASER 36 IutHf'' t «herrnan FACT IS 43 INDEPENDENT BITZ 44 LETTERS 47/48 BADGE OFFER 48 GIGZ 50 chorus Repeat Editor Editorial Assistants Contributors Ian Cranna Bev Hillier Robin Katz Linda Duff Red Starr 9" 1 nts you to be Fred Dellar hw •"" STKiBut I II artT Advertisement w my deaf David Hepworlh Manager Mike Stand m V Rod Sopp m the kinda Kelly Pike ' ^ •* who aive" u ju« J Hk. th.t. (Tel: 01-439 8801) Jill Furmanovsky oh no Design Editor Assistant Steve Bush Steve Taylor Adie Hegarty 'roduction Editor Editorial Consultant Publisher Kasperde Graaf Nick Logan Peter Strong to fade Repeat chorus Editorial and Advertising address: Smash Hits, 52-55 Carnaby Street, London W1V 1PF. -

City of Angels

ZANFAGNA CHRISTINA ZANFAGNA | HOLY HIP HOP IN THE CITY OF ANGELSHOLY IN THE CITY OF ANGELS The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Lisa See Endowment Fund in Southern California History and Culture of the University of California Press Foundation. Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Holy Hip Hop in the City of Angels MUSIC OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Shana Redmond, Editor Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., Editor 1. California Soul: Music of African Americans in the West, edited by Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje and Eddie S. Meadows 2. William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions, by Catherine Parsons Smith 3. Jazz on the Road: Don Albert’s Musical Life, by Christopher Wilkinson 4. Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars, by William A. Shack 5. Dead Man Blues: Jelly Roll Morton Way Out West, by Phil Pastras 6. What Is This Thing Called Jazz?: African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists, by Eric Porter 7. Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop, by Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr. 8. Lining Out the Word: Dr. Watts Hymn Singing in the Music of Black Americans, by William T. Dargan 9. Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba, by Robin D. -

DRAKE BELL Chops Onscreen, Writing the Theme Song “Found a Way” and Playing an Exaggerated LIVE in EUGENE Version of His Guitarist Self Named Drake Parker

K k JANUARY 2020 K g VOL. 32 #1 H WOWHALL.ORGk the side, and after a program he was in, Nickelodeon’s The Amanda Show, was can- celed in 2002, and a spinoff, The Drake and Josh Show, was started (it first aired in 2004), Bell was able to finally show off his DRAKE BELL chops onscreen, writing the theme song “Found a Way” and playing an exaggerated LIVE IN EUGENE version of his guitarist self named Drake Parker. Drake had a starring role in the comedy spoof film Superhero Movie and recorded a theme song for the film called “Superhero! Song”, which was released on April 8, 2008. Bell was cast as Spiderman in the animated TV series: Ultimate Spiderman based on the comic book of the same name. He later reprised the role in The Avengers: Earth’s Mightiest Heroes. He has also voiced the role of Spider-Man in two video games, Marvel Heroes and Disney Infinity: Marvel Super Heroes. With a sound heavily influenced by The Beatles and The Beach Boys, Drake released his debut album, Telegraph, independently in 2005. Soon after he signed to Universal, who put out his sophomore record, It’s Only Time, the following year. The live album, Drake Bell in Concert, appeared in 2008 and in 2011 Drake released the stopgap EP A On Friday, February 8, Vitbrand miere small-screen commercial at age five, in County, California) didn’t start playing the Reminder. Entertainment welcomes Drake Bell to the early ‘90s. Bell commenced A-list film guitar until he was cast in the 2001 TV Returning to the studio some two years Eugene.