Periodontal Health and Systemic Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal Health

International Journal of Dentistry Research 2016; 1(1): 31-33 Review Article Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal IJDR 2016; 1(1): 31-33 December Health © 2016, All rights reserved www.dentistryscience.com Dr. Manpreet Kaur*1, Dr. Krishan Kumar1 1 Department of Periodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak-124001, Haryana, India Abstract Plaque is responsible for periodontal diseases. In order to prevent occurrence and progression of periodontal disease, removal of plaque becomes important. Mechanical tooth cleaning aids such as toothbrushes, dental floss, interdental brushes are used for removal of plaque. However, in some cases, chemical agents are used as an adjunct to mechanical methods to facilitate plaque control and prevent gingivitis. Chlorhexidine (CHX) mouthwash is the most commonly used and is considered as gold standard chemical agent. In this review, mechanism of action and other properties of CHX are discussed. Keywords: Plaque, Chemical agents, Chlorhexidine (CHX). INTRODUCTION Dental plaque is primary etiologic factor responsible for gingivitis and periodontitis [1]. Mechanical plaque control using toothbrushes, interdental brushes, dental floss prevent occurrence of gingivitis. However, in majority of population, mechanical methods of plaque control are ineffective due to less time spent[2] for plaque removal and lack of consistency. These limitations necessitate use of chemical plaque control agents as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control. Among various chemical agents, chlorhexidine (CHX) is considered to be a gold standard chemical agent for plaque control. Its structural formula consists of two symmetric 4-chlorophenyl rings and two biguanide groups connected by a central hexamethylene chain. Mechanism of action for CHX CHX is bactericidal and is effective against gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria and yeast organisms. -

DENTIN HYPERSENSITIVITY: Consensus-Based Recommendations for the Diagnosis & Management of Dentin Hypersensitivity

October 2008 | Volume 4, Number 9 (Special Issue) DENTIN HYPERSENSITIVITY: Consensus-Based Recommendations for the Diagnosis & Management of Dentin Hypersensitivity A Supplement to InsideDentistry® Published by AEGISPublications,LLC © 2008 PUBLISHER Inside Dentistry® and De ntin Hypersensitivity: Consensus-Based Recommendations AEGIS Publications, LLC for the Diagnosis & Management of Dentin Hypersensitivity are published by AEGIS Publications, LLC. EDITORS Lisa Neuman Copyright © 2008 by AEGIS Publications, LLC. Justin Romano All rights reserved under United States, International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a PRODUCTION/DESIGN Claire Novo retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. The views and opinions expressed in the articles appearing in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the editors, the editorial board, or the publisher. As a matter of policy, the editors, the editorial board, the publisher, and the university affiliate do not endorse any prod- ucts, medical techniques, or diagnoses, and publication of any material in this jour- nal should not be construed as such an endorsement. PHOTOCOPY PERMISSIONS POLICY: This publication is registered with Copyright Clearance Center (CCC), Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. Permission is granted for photocopying of specified articles provided the base fee is paid directly to CCC. WARNING: Reading this supplement, Dentin Hypersensitivity: Consensus-Based Recommendations for the Diagnosis & Management of Dentin Hypersensitivity PRESIDENT / CEO does not necessarily qualify you to integrate new techniques or procedures into your practice. AEGIS Publications expects its readers to rely on their judgment Daniel W. -

Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters

microorganisms Article Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters Andrea Butera , Simone Gallo * , Carolina Maiorani, Domenico Molino, Alessandro Chiesa, Camilla Preda, Francesca Esposito and Andrea Scribante * Section of Dentistry–Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Paediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (F.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Periodontitis consists of a progressive destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. Considering that probiotics are being proposed as a support to the gold standard treatment Scaling-and-Root- Planing (SRP), this study aims to assess two new formulations (toothpaste and chewing-gum). 60 patients were randomly assigned to three domiciliary hygiene treatments: Group 1 (SRP + chlorhexidine-based toothpaste) (control), Group 2 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste) and Group 3 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste + probiotics-based chewing-gum). At baseline (T0) and after 3 and 6 months (T1–T2), periodontal clinical parameters were recorded, along with microbiological ones by means of a commercial kit. As to the former, no significant differences were shown at T1 or T2, neither in controls for any index, nor in the experimental -

Gingival Recession – Etiology and Treatment

Preventive_V2N2_AUG11:Preventive 8/17/2011 12:54 PM Page 6 Gingival Recession – Etiology and Treatment Mark Nicolucci, D.D.S., M.S., cert. perio implant, F.R.C.D.(C) Murray Arlin, D.D.S., dip perio, F.R.C.D.(C) his article focuses on the recognition and reason is often a prophylactic one; that is we understanding of recession defects of the want to prevent the recession from getting T oral mucosa. Specifically, which cases are worse. This reasoning is also true for the esthetic treatable, how we treat these cases and why we and sensitivity scenarios as well. Severe chose certain treatments. Good evidence has recession is not only more difficult to treat, but suggested that the amount of height of keratinized can also be associated with food impaction, or attached gingiva is independent of the poor esthetics, gingival irritation, root sensitivity, progression of recession (Miyasato et al. 1977, difficult hygiene, increased root caries, loss of Dorfman et al. 1980, 1982, Kennedy et al. 1985, supporting bone and even tooth loss . To avoid Freedman et al. 1999, Wennstrom and Lindhe these complications we would want to treat even 1983). Such a discussion is an important the asymptomatic instances of recession if we consideration with recession defects but this article anticipate them to progress. However, non- will focus simply on a loss of marginal gingiva. progressing recession with no signs or Recession is not simply a loss of gingival symptoms does not need treatment. In order to tissue; it is a loss of clinical attachment and by know which cases need treatment, we need to necessity the supporting bone of the tooth that distinguish between non-progressing and was underneath the gingiva. -

Pathological and Therapeutic Approach to Endotoxin-Secreting Bacteria Involved in Periodontal Disease

toxins Review Pathological and Therapeutic Approach to Endotoxin-Secreting Bacteria Involved in Periodontal Disease Rosalia Marcano 1, M. Ángeles Rojo 2 , Damián Cordoba-Diaz 3 and Manuel Garrosa 1,* 1 Department of Cell Biology, Histology and Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine and INCYL, University of Valladolid, 47005 Valladolid, Spain; [email protected] 2 Area of Experimental Sciences, Miguel de Cervantes European University, 47012 Valladolid, Spain; [email protected] 3 Area of Pharmaceutics and Food Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, and IUFI, Complutense University of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: It is widely recognized that periodontal disease is an inflammatory entity of infectious origin, in which the immune activation of the host leads to the destruction of the supporting tissues of the tooth. Periodontal pathogenic bacteria like Porphyromonas gingivalis, that belongs to the complex net of oral microflora, exhibits a toxicogenic potential by releasing endotoxins, which are the lipopolysaccharide component (LPS) available in the outer cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. Endotoxins are released into the tissues causing damage after the cell is lysed. There are three well-defined regions in the LPS: one of them, the lipid A, has a lipidic nature, and the other two, the Core and the O-antigen, have a glycosidic nature, all of them with independent and synergistic functions. Lipid A is the “bioactive center” of LPS, responsible for its toxicity, and shows great variability along bacteria. In general, endotoxins have specific receptors at the cells, causing a wide immunoinflammatory response by inducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the production of matrix metalloproteinases. -

Classifications for Gingival Recession: a Mini Review

Galore International Journal of Health Sciences and Research Vol.3; Issue: 1; Jan.-March 2018 Website: www.gijhsr.com Review Article P-ISSN: 2456-9321 Classifications for Gingival Recession: A Mini Review Dr Amit Mani1, Dr. Rosiline James2 1Professor and HOD, Dept. of Periodontics, 2Post graduate student, Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, Loni, India Corresponding Author: Rosiline James _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT the treatment. The following are the classifications for gingival recession. Gingival Recession is a common problem 1. Sullivan and Atkins (1968) associated with or without Periodontitis. It can The basis for the classification was depth be associated with many etiological factors. The and width of the defect. one of the common factor is faulty tooth The four categories were: brushing trauma. There are other factors too which contribute to the gingival recession. Not Deep wide only Gingival Recession causes an esthetic Shallow wide problem but also causes hypersensitivity and Deep narrow associated caries. This paper reviews the various Shallow narrow. classifications for gingival recession which can This classification though simple is be useful for the proper diagnosis and treatment. subjected to open interpretation of the examiner and inter examiner variability and Keywords: Gingival Recession, Classification is therefore not reproducible. [3] for Gingival Recession, Palatal recession INTRODUCTION Gingival recession is defined as an apical shift of the gingival margin (GM) from its position 1 mm coronal to or at the level of the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) with exposure of the root surface to the oral environment. [1] The displacement of marginal tissue apical to the cemento- enamel junction (CEJ). [2] The term “marginal tissue recession” has been considered to be more accurate than “gingival recession,” since the marginal Figure 1: Sullivan & Atkins Classification tissue may have been what is known as alveolar mucosa. -

Desensitizing Agent Reduces Dentin Hypersensitivity During Ultrasonic Scaling: a Pilot Study Dentistry Section

Original Article DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13775.6495 Desensitizing Agent Reduces Dentin Hypersensitivity During Ultrasonic Scaling: A Pilot Study Dentistry Section TOMONARI SUDA1, HIROAKI KOBAYASHI2, TOSHIHARU AKIYAMA3, TAKUYA TAKANO4, MISA GOKYU5, TAKEAKI SUDO6, THATAWEE KHEMWONG7, YUICHI IZUMI8 ABSTRACT of the dentin hypersensitivity agent. Evaluation of effects on Background: Dentin hypersensitivity can interfere with optimal dentin hypersensitivity was determined by a questionnaire and periodontal care by dentists and patients. The pain associated visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores after ultrasonic scaling. with dentin hypersensitivity during ultrasonic scaling is intolerable The statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student for patient and interferes with the procedure, particularly during t-test and Spearman rank correlation coefficient. supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) for patients with gingival Results: The desensitizing agent reduced the mean VAS pain recession. score from 69.33 ± 16.02 at baseline to 26.08 ± 27.99 after Aim: This study proposed to evaluate the desensitizing effect of application. The questionnaire revealed that >80% patients the oxalic acid agent on pain caused by dentin hypersensitivity were satisfied and requested the application of the desensitizing during ultrasonic scaling. agent for future ultrasonic scaling sessions. Materials and Methods: This study involved 12 patients who Conclusion: This study shows that the application of the oxalic were incorporated in SPT program and complained of dentin acid agent considerably reduces pain associated with dentin hypersensitivity during ultrasonic scaling. We examined the hypersensitivity experienced during ultrasonic scaling. This availability of the oxalic acid agent to compare the degree of pain control treatment may improve patient participation and pain during ultrasonic scaling with or without the application treatment efficiency. -

Periodontal Practice Patterns

PERIODONTAL PRACTICE PATTERNS A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Janel Kimberlay Yu, D.D.S. Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angelo Mariotti, Advisor Dr. Jed Jacobson Dr. Eric Seiber Copyright by Janel Kimberlay Yu 2010 Abstract Background: Differences in the rates of dental services between geographic regions are important since major discrepancies in practice patterns may suggest an absence of evidence-based clinical information leading to numerous treatment plans for similar dental problems and the misallocation of limited resources. Variations in dental care to patients may result from characteristics of the periodontist. Insurance claims data in this study were compared to the characteristics of periodontal providers to determine if variations in practice patterns exist. Methods: Claims data, between 2000-2009 from Delta Dental of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, New Mexico, and Tennessee, were examined to analyze the practice patterns of 351 periodontists. For each provider, the average number of select CDT periodontal codes (4000-4999), implants (6010), and extractions (7140) were calculated over two time periods in relation to provider variable, including state, urban versus rural area, gender, experience, location of training, and membership in organized dentistry. Descriptive statistics were performed to depict the data using measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion. ii Results: Differences in periodontal procedures were present across states. Although the most common surgical procedure in the study period was osseous surgery, greater increases over time were observed in regenerative procedures (bone grafts, biologics, GTR) when compared to osseous surgery. -

Peri-Implantitis: a Review of the Disease

DENTISTRY ISSN 2377-1623 http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/DOJ-2-117 Open Journal Review Peri-Implantitis: A Review of the Disease *Corresponding author and Report of a Case Treated with Zeeshan Sheikh, Dip.Dh, BDS, MSc, PhD Department of Dentistry Allograft to Achieve Bone Regeneration University of Toronto Room 222 Fitzgerald Building 150 College Street Toronto, ON M5S 3E2, Canada Haroon Rashid1#, Zeeshan Sheikh2#*, Fahim Vohra3, Ayesha Hanif1 and Michael Glogauer2 Tel. +1-416-890-2289 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] #These authors contributed equally Volume 2 : Issue 3 1Division of Prosthodontics, College of Dentistry, Ziauddin University, Karachi, Pakistan Article Ref. #: 1000DOJ2117 2Matrix Dynamics Group, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Canada 3College of Dentistry, Division of Prosthodontic, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Article History Received: September 20th, 2015 Accepted: October 1st, 2015 ABSTRACT Published: October 5th, 2015 Dental implants offer excellent tooth replacement options however; peri-implantitis can limit their clinical success by causing failure. Peri-implantitis is an inflammatory process Citation around dental implants resulting in bone loss in association with bleeding and suppuration. Rashid H, Sheikh Z, Vohra F, Hanif A, Glogauer M. Peri-implantitis: a review Dental plaque is at the center of its etiology, and in addition, systemic diseases, smoking, and of the disease and report of a case parafunctional habits are also implicated. The pathogenic species associated with peri-implan- treated with allograft to achieve bone titis include, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Tanner- regeneration. Dent Open J. 2015; ella forsythia. The goal in the management of peri-implantitis is the complete resolution of 2(3): 87-97. -

Diagnosis Questions and Answers

1.0 DIAGNOSIS – 6 QUESTIONS 1. Where is the narrowest band of attached gingiva found? 1. Lingual surfaces of maxillary incisors and facial surfaces of maxillary first molars 2. Facial surfaces of mandibular second premolars and lingual of canines 3. Facial surfaces of mandibular canines and first premolars and lingual of mandibular incisors* 4. None of the above 2. All these types of tissue have keratinized epithelium EXCEPT 1. Hard palate 2. Gingival col* 3. Attached gingiva 4. Free gingiva 16. Which group of principal fibers of the periodontal ligament run perpendicular from the alveolar bone to the cementum and resist lateral forces? 1. Alveolar crest 2. Horizontal crest* 3. Oblique 4. Apical 5. Interradicular 33. The width of attached gingiva varies considerably with the greatest amount being present in the maxillary incisor region; the least amount is in the mandibular premolar region. 1. Both statements are TRUE* 39. The alveolar process forms and supports the sockets of the teeth and consists of two parts, the alveolar bone proper and the supporting alveolar bone; ostectomy is defined as removal of the alveolar bone proper. 1. Both statements are TRUE* 40. Which structure is the inner layer of cells of the junctional epithelium and attaches the gingiva to the tooth? 1. Mucogingival junction 2. Free gingival groove 3. Epithelial attachment * 4. Tonofilaments 1 49. All of the following are part of the marginal (free) gingiva EXCEPT: 1. Gingival margin 2. Free gingival groove 3. Mucogingival junction* 4. Interproximal gingiva 53. The collar-like band of stratified squamous epithelium 10-20 cells thick coronally and 2-3 cells thick apically, and .25 to 1.35 mm long is the: 1. -

Classification and Diagnosis of Aggressive Periodontitis

Received: 3 November 2016 Revised: 11 October 2017 Accepted: 21 October 2017 DOI: 10.1002/JPER.16-0712 2017 WORLD WORKSHOP Classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis Daniel H. Fine1 Amey G. Patil1 Bruno G. Loos2 1 Department of Oral Biology, Rutgers School Abstract of Dental Medicine, Rutgers University - Newark, NJ, USA Objective: Since the initial description of aggressive periodontitis (AgP) in the early 2Department of Periodontology, Academic 1900s, classification of this disease has been in flux. The goal of this manuscript is to Center of Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), review the existing literature and to revisit definitions and diagnostic criteria for AgP. University of Amsterdam and Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Study analysis: An extensive literature search was performed that included databases Correspondence from PubMed, Medline, Cochrane, Scopus and Web of Science. Of 4930 articles Dr. Daniel H. Fine, Department of Oral reviewed, 4737 were eliminated. Criteria for elimination included; age > 30 years old, Biology, Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, Rutgers University - Newark, NJ. abstracts, review articles, absence of controls, fewer than; a) 200 subjects for genetic Email: fi[email protected] studies, and b) 20 subjects for other studies. Studies satisfying the entrance criteria The proceedings of the workshop were were included in tables developed for AgP (localized and generalized), in areas related jointly and simultaneously published in the Journal of Periodontology and Journal of to epidemiology, microbial, host and genetic analyses. The highest rank was given to Clinical Periodontology. studies that were; a) case controlled or cohort, b) assessed at more than one time-point, c) assessed for more than one factor (microbial or host), and at multiple sites. -

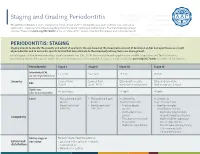

Staging and Grading Periodontitis

Staging and Grading Periodontitis The 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions resulted in a new classification of periodontitis characterized by a multidimensional staging and grading system. The charts below provide an overview. Please visit perio.org/2017wwdc for the complete suite of reviews, case definition papers, and consensus reports. PERIODONTITIS: STAGING Staging intends to classify the severity and extent of a patient’s disease based on the measurable amount of destroyed and/or damaged tissue as a result of periodontitis and to assess the specific factors that may attribute to the complexity of long-term case management. Initial stage should be determined using clinical attachment loss (CAL). If CAL is not available, radiographic bone loss (RBL) should be used. Tooth loss due to periodontitis may modify stage definition. One or more complexity factors may shift the stage to a higher level. Seeperio.org/2017wwdc for additional information. Periodontitis Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Interdental CAL 1 – 2 mm 3 – 4 mm ≥5 mm ≥5 mm (at site of greatest loss) Severity Coronal third Coronal third Extending to middle Extending to middle RBL (<15%) (15% - 33%) third of root and beyond third of root and beyond Tooth loss No tooth loss ≤4 teeth ≥5 teeth (due to periodontitis) Local • Max. probing depth • Max. probing depth In addition to In addition to ≤4 mm ≤5 mm Stage II complexity: Stage III complexity: • Mostly horizontal • Mostly horizontal • Probing depths • Need for