Chapter 3.British Period (1796 -1948)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Company Profile- Civil.Pdf

CHANCEENGINEERING PRIVATE LIMITED THE COMPANY Company & Registration No : CHANCE ENGINEERING (PVT) LTD – PV 12295 Constitution : Private Limited Country of Incorporation : Sri Lanka Date of Incorporation : 13th of February 2002 Registered Address: : No: 73, Dharmapala Place, Rajagiriya, Sri Lanka Correspondence: : No: 73, Dharmapala Place, Rajagiriya, Sri Lanka Of�ice Tel. No : 0112-889316 Of�ice Fax No : 0112-889314 Business Enquiry Email : [email protected] ICTAD Registration No : C-7150, S- 0162 ICTAD Grade : C-5, EM 1 NCASL No : R-4270 Company secretary : U.D.Kulathunga (LLB (SL) Attorney at law) Auditors : H.A. Wehella & Company CHANCE ENGINEERING (PVT) LTD 1 CHANCEENGINEERING PRIVATE LIMITED Chance Engineering (PVT) Ltd. In the �ields of Electrical, Mechani- cal & Civil Engineering, the process is that consists of the building or assembling of infrastructure. At Chance, we understand that we play an important role as an engine of growth and a partner in success for more than hundred of individuals, families and busi- nesses. We built this company with a focus on serving the common man through the commissioning of world- class Applications in Electrical, Mechanical & civil Engineering that would enhance life quality. Our ability to support the well-being of those we serve. Also we provide solutions that spread the largest good to the widest number and taking a decisive step in this direction and in order to build a strong brand for the Company. We have a quali�ied and experienced staff in-house and the construction sites are well supervised and managed until the projects are completed. It has always met the requirements of the Clients and the Consultants and has proven it by completing the Projects on time to their entire satisfaction. -

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka November 2017 Dimantha De Silva, Ph.D(Calgary), P.Eng.(Alberta) Senior Lecturer, University of Moratuwa 1 SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Table of Content Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background and Purpose .............................................................................................................. 4 Study Area .................................................................................................................................... 5 Existing Transport Master Plans .................................................................................................. 6 Indicator 1: Extent to which Transport Plans Cover Public Transport, Intermodal Facilities and Infrastructure for Active Modes ............................................................................................... 7 Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 8 Indicator 2: Modal Share of Active and Public Transport in Commuting................................. 13 Summary ................................................................................................................................... -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

Battle of the “Species” to Play the Role of “National Bourgeoisie”: a Reading of Shyam Selvadurai's Cinnamon Gardens A

9ROXPH,,,,VVXH9-XO\,661 Battle of the “Species” to play the Role of “National bourgeoisie”: A Reading of Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy Niku Chetia Gauhati University India Decolonization is quite simply the replacing of a certain “species” of men by another “species” of men. (Fanon, 1963) Fanon had quite rightly pointed out in his work, The Wretched of the Earth (1961) that during the colonial and post-colonial period, the battle for dominating, suppressing and subjugating certain groups of people by a superior class never ceases to exist. He explains that there are two species- “Colonisers” and “National bourgeoisie” of the colonised- who seeks to rule the country after independence. Though he places his ideas in an African context, his arguments seems valid even for a South-East Asian country like Sri Lanka. After colonisers left the nation, there emerged a pertinent question - Who would play the role of national bourgeoisie? The struggle to play the coveted role drives Sri Lanka through ethnic conflicts and prejudices among them. The two dominant “species” battling for the position are: Tamils and Sinhalese. Considering the Marxist model of society, Althusser in work On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses claims that the social structure is composed of Base and Superstructure. The productive forces (labour forces/working class) and relations of production forms the Base while religious ideology, ethics, politics, family, identity and politico-legal (law and state) forms the superstructure (237). The National bourgeoisie exists in the superstructure. Both the groups try to survive in the superstructure.The objective of this paper is to study Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy and excavate the diverse ways in which these two mammoth ethnic groups struggle to oust one another and form the “national bourgeoisie”. -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

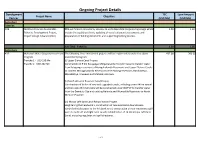

Ongoing Project Details

Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) Agriculture Fisheries ADB Northern Province Sustainable PDA will finance consultancy services to undertake detail engineering design which 1.59 1.30 Fisheries Development Project, include the updating of cost, updating of social safeguard assessments and Project Design Advance (PDA) preparation of bidding documents and supporting bidding process. Sub Total - Fisheries 1.59 1.30 Agriculture ADB Mahaweli Water Security Investment The following three investment projects will be implemented under the above 432.00 360.00 Program investment program. Tranche 1 - USD 190 Mn (i) Upper Elahera Canal Project Tranche 2- USD 242 Mn Construction of 9 km Kaluganga-Morgahakanda Transfer Canal to transfer water from Kaluganga reservoir to Moragahakanda Reservoirs and Upper Elehera Canals to connect Moragahakanda Reservoir to the existing reservoirs; Huruluwewa, Manakattiya, Eruwewa and Mahakanadarawa. (ii) North Western Province Canal Project Construction of 96 km of new and upgraded canals, including a new 940 m tunnel and two new 25 m tall dams will be constructed under NWPCP to transfer water from the Dambulu Oya and existing Nalanda and Wemedilla Reservoirs to North Western Province. (iii) Minipe Left Bank Canal Rehabilitation Project Heightening the headwork’s, construction of new automatic downstream- controlled intake gates to the left bank canal; construction of new emergency spill weirs to both left and right bank canals; rehabilitation of 74 km Minipe Left Bank Canal, including regulator and spill structures. 1 of 24 Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) IDA Agriculture Sector Modernization Objective is to support increasing Agricultural productivity, improving market 125.00 125.00 Project access and enhancing value addition of small holder farmers and agribusinesses in the project areas. -

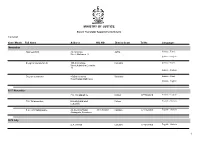

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Technical Assistance Consultant's Report Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: National Port Master Plan

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 50184-001 February 2020 Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: National Port Master Plan (Financed by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction) The Colombo Port Development Plan – Volume 2 (Part 3) Prepared by Maritime & Transport Business Solutions B.V. (MTBS) Rotterdam, The Netherlands For Sri Lanka Ports Authority This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Figure 8-16 Warehouse Logistics Process Three main flows can be identified: • Incoming flow: products or goods discharged from a truck or unloaded from a container. • Warehousing cargo flow: storage of the palletised goods within the warehouse and – if applicable – registration/follow-up of additional value added activities like re-packing, labelling, price-marking, etc. • Outgoing flow: products or goods leaving the warehouse via truck or loaded into a container. The use of pallets is one of the basic and most fundamental requirements of modern warehousing activities and operations. All incoming cargo or products that are not yet palletised need to be stacked on (standardised) pallets during or directly after unloading a truck or un-stuffing a container. A dedicated follow-up of pallet stock management is of paramount importance to carry on the logistics activities. After palletising the goods, the content of each pallet needs to be inventoried and this data needs to flow into the warehouse management system. -

Colombo Hotels Page 1 of 4

ypically, the weather in Colombo is warm and sunny, with a chance of rain at certain times of the year. Average temperature (in degree Celsius) April to October: 33.5°C November to April: 25°C Population: 600,000 Sightseeing Explore a new area. Be inspired by another culture. The Gateway Hotel wants to help you get as much as possible out of every travel experience. Here are some local attractions and intriguing destinations we think you'll like. 01 Museums Attractions near the hotel include the National Museum of Colombo, the Natural History Museum and the Dutch Period Museum. It is also worth visiting the Galle Face Green Promenade and the local zoo, which hosts an elephant show every day. 02 Day tour to Wilpattu National Park Close to Anuradhapura is unique in its topography having several inland 'Villus' (lakes) that attract thousands of water birds. It is the domain of the elusive leopard. Bear and herds of deer and sambhur are common. 03 Day tour to Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage Is very popular and visited daily by many Sri Lankan and foreign tourists. The main attraction is clearly to observe the bathing elephants from the tall river bank as it allows visitors to observe the herd interacting socially, bathing and playing. This 24 acre elephant orphanage is also a breeding place for elephants. Twenty elephants have been born since 1984, and the orphanage has the largest herd of captive elephants in the world. 04 Day tour to Kandy "The name Kandy comes from the Sinhala name Kanda Udarata which means The Country over the mountains. -

VISTA POINT Reisemagazin Asien

Ausgabe 1/2016 • 1. Jahrgang VISTA POINT Reisemagazin TRAUMSTRÄNDE ANDERE LÄNDER – ANDERE SITTEN UNESCO-WELTERBESTÄTTEN © mauritius images/Age © INKL. LESE- ASIEN PROBE BALI · VIETNAM · THAILAND · SRI LANKA Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser, was erinnert Sie nach Ihrer Rückkehr an die letzte Reise? Sind es die abge- tretenen Schuhe, die Sandkörner im Koffer oder die vielen Fotos auf der Speicherkarte der Kamera? Wie hält man die Ehrfurcht fest, die den Reisenden am Gipfel eines Berges oder beim Anblick uralter Kulturstät- ten ergreift? Seit 1988 fassen unsere Autoren für iStockphoto/Radiuz © Sie Ihre Erfahrungen und Erlebnisse in Worte und schreiben über die schöns- Das VISTA POINT Reisemagazin, unser ten Reiseziele dieser Welt. E-Magazin, gibt es ausschließlich im Genauso lange verlegen wir Reiseführer digitalen Format. Es stellt die span- mit dem Anspruch, den perfekten Reise- nendsten Regionen dieser Welt vor und begleiter für Sie zu gestalten – und das liefert in einer bunten Themenmischung nicht nur im klassischen Printmedium, Wissenswertes, Kurioses und Spannen- sondern auch aktuell in digitaler des zu Ihrem vielleicht nächsten Reise- Form. So wie unsere Apps und E-Books, ziel und darüber hinaus. die wir stets am Puls der Zeit und mit Blick auf die neuesten Trends entwi- Ihre ckeln. VISTA POINT Redaktion Herzlich willkommen! Dies ist die erste Ausgabe des VISTA POINT Reisemagazins, das Sie auf den asiati- schen Kontinent entführen möchte. Die renommierten VISTA POINT-Autoren stel- len Ihnen die schönsten Strände, die kulinarischen Genüsse sowie ausgewählte kulturelle und landschaftliche Highlights von Thailand, Vietnam, Bali und Sri Lanka vor. 2 INHALT Unser Titelbild zeigt einen Reisbauern im Cuc- Phuong-Nationalpark in Vietnam. -

T H3586 Possibilities of Reducing Train Delays

/,©/ VOW ( Cfr/ f SLO/g POSSIBILITIES OF REDUCING TRAIN DELAYS BETWEEN COLOMBO FORT AND MARADANA LIBRARY (jur/ERSSTY OF MORATUWA, SFJ LAHKA mor*tuwa Vithanage Chinthaka Dasun Jayasekara (138327B) Degree of Master of Science Department of Civil Engineering V-/ 3 5 86 4 University of Moratuwa £ V Qor-3 Sri Lanka May 2017 University of Murtiluwn Jf » 6^4 \~r TH3586 S5 G T H3586 POSSIBILITIES OF REDUCING TRAIN DELAYS BETWEEN COLOMBO FORT AND MARADANA Vithanage Chinthaka Dasun Jayasekara (138327B) Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Transportation Department of Civil Engineering University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka May 2017 DECLARATION OF THE CANDIDATE AND SUPERVISOR “I declare that this is my own work and this thesis does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any other University or Institute of higher learning and to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not any material previously published or written by another person except where the acknowledgement is made in the text. Also, I hereby grant to University of Moratuwa the non-exclusive right to reproduce and distribute my thesis, in whole or in part in print, electronic or other medium. I retain the right to use this content in whole or parts in future works (such as articles or books) 20 \ ^ Signature: Date: o & The above candidate has carried out research for the Masters Dissertation under my supervision. c?o e>xoir Signature of the supervisor: Date: 1 ABSTRACT Sri Lanka Railways (SLR) is operating around 300 passenger train movements daily across its 1400 Km rail network. -

Galle Face Green

Galle Face Green Laid out in 1857 by the British governor Sir Henry Ward, Galle Face Green is a park separating the hectic life of Colombo and the Indian Ocean. The green is the city's largest open space and a popular spot during sunset, when hundreds of Sri Lankans come to fly kites, play cricket and eat ice cream. We walked along the green one evening, just as the sun was tucking itself behind the clouds over the ocean. One of the great things about Sri Lanka's being so close to the equator is that the sun rises and sets around the same time all year round. So regardless of when you're visiting Colombo, make sure to head to Galle Face Green at around 6:30pm. If you get lucky, you'll enjoy a spectacular sunset and marvel as the city turns a strange, deep shade of crimson. At the end of the green is the historic Galle Face Hotel, a beautiful lodging which retains much of its colonial charm. The hotel's best feature is its veranda, with chairs and tables facing out to sea. Unsurprisingly, it's one of the city's most popular spots for an evening drink. We sat down and, after sending the waiter to fetch a couple Three Coins lagers, felt as though we'd fallen back through time. So this is how the British lords of colonial Ceylon lived. Not bad. The breeze coming off the ocean was wonderful, the beers cold and delicious, the view unbeatable, the service spectacular, and the other patrons well-dressed and in pleasant moods.