World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WANDA: a Measurement Tool for Forensic Document Examiners Measurement Science and Standards in Forensic Handwri�Ng Analysis, NIST Campus, Conference & Webcast 4./5

A FISH called WANDA, 2013 A FISH called WANDA! WANDA: A Measurement Tool for Forensic Document Examiners Measurement Science and Standards in Forensic HandwriCng Analysis, NIST Campus, Conference & Webcast 4./5. June 2013 Katrin Franke, Department of Computer Science and Media Technology, Gjøvik University College hp://www.nislab.no Forensics Lab 1 A FISH called WANDA, 2013 Katrin Franke, PhD, Professor § Professor of Computer Science, 2010 PhD in ArCficial Intelligence, 2005 MSc in Electrical Engineering, 1994 § Industrial Research and Development (19+ years) Financial Services and Law Enforcement Agencies § Courses, Tutorials and post-graduate Training: Law Enforcement, BSc, MSc, PhD § Chair IAPR/TC6 – Computaonal Forensics, 2008-2012 § IAPR Young InvesCgator Award, 2009 Internaonal Associaon of Paern RecogniCon Forensics Lab 2 kyfranke.com A FISH called WANDA, 2013 Current Affilia7on § Norwegian Information Security Laboratory (NISlab) Department of Computer Science and Media Technology, Gjøvik University College, P.O. Box 191, N-2802 Gjøvik, Norway. § http://www.nislab.no Forensics Lab 3 KyFranke - ICDAR 2007 - Tutorial - Computational Forensics 3 A FISH called WANDA, 2013 Disclaimer § The following slides have been published previously, i.e. § Franke, K., Schomaker, L., Vuurpijl, L., Giesler, S. (2003). FISH-New: A common ground for computer-based forensic writer identification (Abstract). Forensic Science International, Volume 136(S1-S432) p. 84, Proc. 3rd European Academy of Forensic Science Triennial Meeting, Istanbul, Turkey. § Franke, K. (2004). Digital image processing and pattern recognition in the forensic analysis of handwriting (Abstract). In Proc. 6th International Congress of the Gesellschaft für Forensischen Schriftenuntersuchung (GFS), Heidelberg, Germany. § Franke, K., Rose, S. (2004). Ink-deposition model: The relation of writing and ink deposition processes. -

Technical Description Mechanical Pencil Portfolio

The Mechanical Pencil A Technical Description The mechanical pencil is a reusable wri�ng instrument that uses a lead-advance mechanism to extend rods of graphite lead forward. The mechanical pencil is most commonly used for drawing pictures, designs or symbols, and wri�ng text on paper. Tombow Pencil Co. is recognized for high-quality mechanical pencils, and mul�farious erasers. This document uses the Tombow Mono Graph pencil (as a model) to describe the features and components of a mechanical pencil. Features The mechanical pencil is a precision wri�ng instrument more commonly used for drawing than wooden pencils and uses either dra�ing lead or thin leads. Graphic art, technical drawing, and wri�ng professionals use the mechanical pencil to create a line of constant thickness. (see fig. 1) • Life�me reusable holder • Individual replacemtn of graphite lead rods • Pencil never decreases in size or need to be sharpened • Rubber gripping prevents callus buildup under the middle finger joint The mechanical pencil combines the features of a wooden pencil and a ballpoint pen. It can be held in the palm of a hand and is made of hi-impact plas�c or metal. Approximately one-third of the mechanical pencil is wrapped with so� black rubber for gripping between the thumb, index, and middle finger while wri�ng or drawing. The clamp holder (or clip), located at the top, can slide into a T-shirt breast pocket allowing for hands-free carrying and easy access. Types There are three basic types of mechanisms used to extend the graphite lead in the mechanical pencil. -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Legal Studies Social and Behavioral Studies 1996 Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents Joe Nickell University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Nickell, Joe, "Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents" (1996). Legal Studies. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_legal_studies/1 Detecting Forgery Forensic Investigation of DOCUlllen ts .~. JOE NICKELL THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1996 byThe Universiry Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2005 The Universiry Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine Universiry, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky Universiry, The Filson Historical Sociery, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Sociery, Kentucky State University, Morehead State Universiry, Transylvania Universiry, University of Kentucky, Universiry of Louisville, and Western Kentucky Universiry. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales qtJices:The Universiry Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: Nickell,Joe. Detecting forgery : forensic investigation of documents I Joe Nickell. p. cm. ISBN 0-8131-1953-7 (alk. paper) 1. Writing-Identification. 2. Signatures (Writing). 3. -

Effectofvariousw00ayri.Pdf

THE EFFECT OF VARIOUS WRITING TOOLS ON THE HANDWRITING LEGIBILITY OF FIRST GRADE CHILDREN By BEULAH M. AYRIS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1981 Tt gives me great pleasure and a deep sense of satisfaction to dedicate this volume to my loving and wonderful mother, Mrs. Aubra Jane Haynie. Throughout my life, she has given so freely of her time and energ}', faith and emotional support in all my endeavors. This study makes her dream a reality. I wish to express sincere gratitude to my husband, Art, and my three children, Arthur, Cynthia and David, for all the patience and tolerance they have shown with household chaos and turmoil during my many months of study. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisory committee: Dr. Linda L. Lamme for her patient guidance in the development of this study, her wisdom as a teacher and for her true friendship; Dr. William Hedges for his kindness and support in the data analysis and for his faith in me as a student; Dr. Dorene Ross for her help in conceptualizing and critiquing the study; Dr. Evelyn Wenzel who has consistently conveyed a feeling of genuine enthusiasm in the development of the study; Dr. Cecil Mercer who has given time and support for the study. This research would not have been possible without the professional support of the first grade teachers who so patiently and conscientiously made daily use of the writing tools in their classrooms for a full semester My aide, Mrs. -

2021 Premium Business Gifts Advertise with Lamy

2021 Premium Business Gifts Advertise with Lamy Fountain pens Ballpoint pens Rollerball pens Mechanical pencils Multisystem pens Notebooks Set offers Lamy’s wide range of promotional articles is available solely to commercial enterprises, businesses and Contents freelancers. Private sale is not possible. Sending a lasting message ................... 3 LAMY AL-star EMR ......................... 44 Taking responsibility – shaping the future ....... 4 LAMY twin pen ............................. 46 From Heidelberg into the world ............... 8 LAMY tri pen ............................... 48 LAMY safari . 10 Notebook assortment from Lamy ............. 50 LAMY AL-star .............................. 12 Sets ....................................... 54 LAMY xevo ................................ 14 Cases ..................................... 55 LAMY noto ................................ 16 LAMY ideos ............................... 56 LAMY logo ................................ 18 LAMY studio ............................... 58 LAMY tipo ................................. 28 LAMY scala. 60 LAMY econ ................................ 30 LAMY 2000 ................................ 62 LAMY pur .................................. 32 LAMY 2000 M ............................. 64 LAMY swift ................................ 34 LAMY dialog cc ............................ 66 LAMY cp1 ................................. 36 LAMY dialog .............................. 68 LAMY pico ................................ 38 LAMY imporium ............................ 70 LAMY -

Writing Instruments & Accessories

Writing instruments & Accessories 2015 100 YEARS OF CREATIVITY AND EMOTION Caran d’Ache is delighted to celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2015. Founded in 1915 in Geneva, the company was renamed ‘Caran d’Ache’ in 1924 as a tribute to the famous French illustrator, Emmanuel Poiré. The company initially specialised in graphite and coloured pencils and diversified its activities to include wax oil pastels, mechanical pencils and the first ballpoint pens.T he expansion of the company, combined with the development of the Colour, Writing Instruments and Office ranges, contributed to the international renown of the Manufacture. Therefore, thanks to its rich history, the Caran d’Ache creations have been a true inspiration for many generations of enthusiasts for a hundred years. “COLLECTION Anniversaire” Caran d’ACHE To mark its 100th anniversary, Caran d’Ache invites you to discover a new collection that has been created especially for this occasion. More than 90 art crafts are expressing themselves through unique creations that take their inspiration from five iconic products:T echnograph, Fixpencil, Prismalo, Ecridor and 849. The Caran d’Ache artisans have imagined and designed each of these items to develop a limited edition collection that is already iconic and animated by the famous character “Bonne-Mine”, the historic emblem of Caran d’Ache. TECHNOGRAPH 100 ANS 4 graphite pencils HB, B, 2B, 3B and a sharpener Ref. CA0777.304 PRISMALO 100 ANS 25 watersoluble pencils Ref. CA0999.325 849 100 ANS Metal ballpoint pen and its giant Goliath cartridge Ref. CA0849.100 ECRIDOR 100 ANS Ballpoint pen Guillochage Chevron 100 ans FIXPENCIL 2MM 100 ANS Ref. -

Catalog 2018

We wish one day could offer a range of beautiful, attractive and high quality products in children sta- tionery, work and office, art and creativity to our customers. In this a p p r o a c h we attempt to manufacture and choose the best and the most at- tractive products. we are on the top business posi- tion if we could offer products with a good quality, suitable price and attractive design in the daily life and works. We use every opportunity to apply our ability to find the best talents, raw material, suppliers and manufacturers. we try to be creative in design in the future. Increase our products quality and im- prove our client’s relations. For this reason our company slogan is “friend to good ideas”. We welcome good ideas and at- tempt to help you finding, developing good ideas and make them reality by high quality products. 1 Writing instruments for the people… Owner is everyone’s favorite brand of writing and coloring instruments and accessories. Made of finest quality materials and presented in vibrant and attractive packaging, Owner products make for excellent gifts for adults and children alike. Product Offering: • Pens & Pencils • Mechanical Pencils • Coloring Pencils • Watercolors, Postercolor & Pastels • Markers & Highlighters & more… Owner is an innovative brand of writing and coloring instruments, with a wide selection of vibrant and exciting products on offer. From product and packaging design, through to component and material selection, we are meticulously involved in every step of the process to offer unique and high-quality products, bearing the continually refreshed and modern Owner logo. -

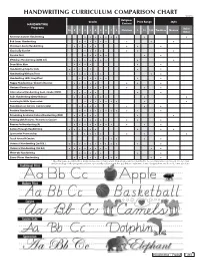

Handwriting Curriculum Comparison Chart

HANDWRITING CURRICULUM COMPARISON CHART ©2018 Religious Grades Price Range Style HANDWRITING Content Programs Italic/ PK K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Christian $ $$ $$$ Tradition Modern Other American Cursive Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Bob Jones Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Christian Liberty Handwriting • • • • • • • • Classically Cursive • • • • • • • Cursive First • • • • • • • D'Nealian Handwriting (2008 ed.) • • • • • • • • • Draw Write Now • • • • • • Handwriting Help for Kids • • • • • • • Handwriting Without Tears • • • • • • • • • Handwriting Skills Simplified • • • • • • • • Happy Handwriting / Cheerful Cursive • • • • • • • • Horizons Penmanship • • • • • • • • • International Handwriting Cont. Stroke (HMH) • • • • • • • Italic Handwriting (Getty-Dubay) • • • • • • • • • Learning to Write Spencerian • • • • • • • • • New American Cursive (cursive only) • • • • • • • Pentime Handwriting • • • • • • • • • • • Preventing Academic Failure Handwriting (PAF) • • • • • • • Printing with Pictures / Pictures in Cursive • • • • • • • • • • Reason for Handwriting (A) • • • • • • • • • • • Sailing Through Handwriting • • • • • • • • • Spencerian Penmanship • • • • • • • Teach Yourself Cursive • • • • • • Universal Handwriting (2nd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • • • • Universal Handwriting (3rd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • • Write-On Handwriting • • • • • • • Zaner-Bloser Handwriting • • • • • • • • • • • *This chart was assembled by Rainbow Resource Curriculum Consultants and is intended to be a comparative tool based on our own understanding of the programs -

Download Catalogue

Design & Production writing instruments and offiDesign ce supplies & Production writing instruments and office supplies SINCE 1951 The ballpoint pen is a Hungarian invention. The idea came from László Bíró, and it materialized with the technical and financial support of Andor Goy. Mr. Andor Goy worked as an engineer at ICO between 1959 and 1976. The original GO–PEN 1946. SINCE 1951 ICO Zrt. 2013 Pomáz, ICO út, 2990 Hrsz. Hungary Telephone: +36 26 527 270, –272, –273 Fax: +36 26 527 269 E-mail: [email protected] www.ico.eu 23 Writing instruments 24 ICO SUNNY mechanical ballpen PCS 48 MIXED COLOURS 30 INK COLOUR: ICO METALLIC F mechanical ballpen PCS 60 MIXED COLOURS 40 INK COLOUR: ICO TATTOO PEN B mechanical ballpen PCS 48 MIXED 40 COLOURS INK COLOUR: 25 ICO SILVER ICE F mechanical ballpen MIXED COLOURS 50 INK COLOUR: ICO GOLF C mechanical ballpen MIXED 12 COLOURS INK COLOUR: ICO GOLF TRENDYM mechanical ballpen MIXED 12 COLOURS INK COLOUR: 26 ICO X-PEN mechanical ballpen MIXED COLOURS 50 PCS 80 INK COLOUR: ICO ORION M mechanical ballpen PCS 80 MIXED COLOURS INK COLOUR: 50 27 ICO OMEGAM mechanical ballpen Set: mechanical ballpen + mechanical pencil MIXED 40 COLOURS INK COLOUR: ICO APOLLO mechanical ballpen PCS 48 MIXED COLOURS 36 INK COLOUR: ICO KAMELEONM mechanical multicolour ballpen 4 colours in 1 pen 4 in 1 INK COLOUR: 50 28 ICO SANTA CLAUS ICO HEART PEN AND KRAMPUS PEN mechanical ballpen mechanical ballpen PCS 48 PCS 20 INK COLOUR: INK COLOUR: ICO RETRO 66 PEN M ICO 70 PEN M mechanical ballpen mechanical ballpen MIXED MIXED COLOURS COLOURS -

Cartooning & Comic Book Illustration

UW-Green Bay Summer Art Studio June 16-21, 2019 Cartooning & Comic Book Illustration Prof. Thomas J. Wallestad, Instructor Welcome Cartooning & Comic Book Illustration Students! ART SUPPLIES Necessary Supplies: *Note: I have listed many optional items below. Prices will vary on art supplies, as does quality. Choices should be based on your wants and needs, as beginners or dabblers need not get the most expensive items. Historically, professionals have used all grades of supplies. It doesn’t matter whether the supplies are expensive or more affordable; it is the results you desire and your ideas that matter. Paper Supplies • Sketchbook- approx. 14” x 17” white sulfite drawing pad suggested (e.g. Strathmore) – for planning the design, before working on good paper for finished art • Choose ONE paper type for finished inked art (2 to 3 sheets): 1. 11” x 17” or bigger- Bristol board (2-ply, hot-pressed smooth) {Best} -OR- 2. 11” x 17” or bigger- non-photo/ non-reproductive blue lined comic art boards (e.g. Blue Line Art) http://www.bluelinepro.com/ Manga size is also available. -OR- 3. 11” x 17” or bigger- any quality smooth and firm drawing paper • Tracing paper (pad or roll) – Vellum (parchment) and Onionskin paper also acceptable Drawing Tools & Drafting Instruments* • An art supply box (e.g. fishing tackle box, tool box, Tupperware, cardboard box, etc) • Several (2H or #4) pencils – Optional other grades of lead hardness (e.g. HB / #2, 3B) • 1 Staedtler or Prismacolor Col-Erase non-photo blue pencil (non-repro) – sketching • Metal pencil -

Handwriting Prepare

Good Practice for Handwriting Prepare... for P checks Posture Paper Pencil Pressure Style Shape Speed Space S Factors Slant for success Size Stringing Sitting together on the line The ‘P checks’ are used to support the process of handwriting and cover Posture, Pencil grasp, Paper position and Pressure and fluency. Poor posture can be a root cause of common handwriting difficulties such as pain or fatigue and will present as a reluctance to write, poor presentation or legibility, slow writing speed and reduced output. Tip Establishing good habits of POSTURE GUIDELINES posture and position early is really helpful. Correcting bad ● Feet flat on the floor or on a wide based raised surface habits later is much more dif- ficult. ● Knees at a right angle with 2-fingers space behind the knee to avoid compression ALTERNATIVE FURNITURE ● Sit on the chair so hips are positioned at approximately 90° with the back supported Adaptive equipment is available for those that struggle with underlying ● Sit approximately a fist-distance away from the table stability, gross and fine motor skills. AND If standing desks are used they ● Table height adjusted so that forearms rest on the top without leaning forward (too low) should also be an appropriate or raising the shoulders/arms (too high) height . Surface - clean, smooth and uncluttered A writing slope can help with wrist ● position and posture. The chair height needs to be higher. TABLE AND CHAIR HEIGHT If the table is at the correct height the forearm is supported, making it easier to control the movement. Too High: children may raise their shoulders induc- ing greater fatigue.