The Following Article Was the First Award Winner of the Trust's Murray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breakfast Programme

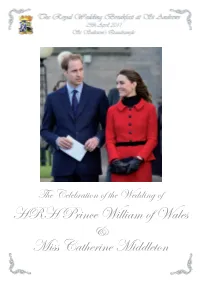

The Celebration of the Wedding of HRH Prince William of Wales & Miss Catherine Middleton Site Map 2 About the Event Today, two of St Andrews’ most famous recent graduates are due to be married in Westminster Abbey in London with the eyes of the world upon them. As the town in which they met and their relationship blossomed, we are delighted to be able to welcome you to our celebrations in honour of the Royal Couple, HRH Prince William of Wales and Miss Catherine Middleton. A variety of entertainment and activities await, building up towards the big moment at around 10:45am where the Royal Couple will be making their entrance into the Abbey for the ceremony itself (due to start at 11am). This will be shown live on the large outdoor screen situated in the main Quadrangle. The “Wedding Breakfast” will be served from 8am on the lower lawn from the marquee with a selection of hot and cold food/drink available. Food will also be on sale throughout the day from local vendors. After the ceremony, and the traditional ‘appearance at the balcony’ the entertainment on the main stage will pick up again, taking the party on to 4pm. The main purpose of the day, aside from having fun, is to raise money for the Royal Wedding Charitable Fund. The list of charities we will be collecting for appears later in the programme. Most of what you see today is provided for free, but we would encourage you to please give generously. The organising committee hope you enjoy this momentous occasion and we are sure you will join with us in extending our warmest wishes and heartfelt congratulations to “Wills & Kate” as they look forward to a long and happy life together. -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Scottish Augustinians: a study of the regular canonical movement in the kingdom of Scotland, c. 1120-1215 Garrett B. Ratcliff Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Classics, and Archaeology University of Edinburgh 2012 In memory of John W. White (1921-2010) and Nicholas S. Whitlock (1982-2012) Declaration I declare that this thesis is entirely my own work and that no part of it has previously been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. N.B. some of the material found in this thesis appears in A. Smith and G. Ratcliff, ‘A Survey of Relations between Scottish Augustinians before 1215’, in The Regular Canons in the Medieval British Isles, eds. J. Burton and K. Stöber (Turnhout, 2011), pp. 115-44. Acknowledgements It has been a long and winding road. -

The Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Replicas for Object Cultural Biographies: Lessons in Duplication from 1830S Fife Sally M

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Aberdeen University Research Archive P a g e | 1 The Legacy of Nineteenth-century Replicas for Object Cultural Biographies: Lessons in Duplication from 1830s Fife Sally M. Foster, Alice Blackwell and Martin Goldberg Replicas are material culture with a direct dependence on more ancient archaeological things, but they also deserve to be treated as things in their own right. As archaeological source material replicas help to complete the biographies of things; they certainly add to our knowledge even if they might occasionally complicate matters. The majority of such replicas date from the second half of the long nineteenth century when large numbers were produced primarily by or for art academies, individuals, antiquarian societies, museums, and art galleries. The term replica has multiple meanings, often with pejorative overtones or a definition contingent on a perceived reduction in authenticity and value (could even imply deception); we use it in the sense of conscious attempts to make direct and accurate copies (facsimiles). Rather than dismiss replicas, we should consider their nature, the circumstances in which they came about, their impact, their changing meanings, and their continuing legacy. For this reason, our nineteenth-century case studies begin with initial replication, when replicas had great value and were used to disseminate information and stimulate discussion about the objects they replicated. Through this intertwining of original and replica as connected parts of the biography of things, we hope to bring about a new realization of the value of replicas in order to demonstrate their continuing potential as often untapped sources of knowledge. -

20 R Trench-Jellicoe

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 135 (2005), 505–559 TRENCH-JELLICOE: KILDUNCAN SLAB | 505 A richly decorated cross-slab from Kilduncan House, Fife: description and analysis * Ross Trench-Jellicoe † ABSTRACT The discovery in late 2001 of a small slab with a sophisticated, innovative and, in part, unique decorative programme near the eastern seaboard of Fife, raises important questions about the cultural affinities and dating of sculpture in Scotland. Analysis of the Kilduncan slab’s carving suggests that the majority of its expected connections of form and ornament lie not with other monuments in eastern-central Scotland but rather in two seemingly mutually exclusive zones: sculpture in a North Sea province, stretching from the shores of the Moray Firth as far as the Northern Isles, Shetland demonstrating particularly strong affinities; and another yet further afield in an Irish Sea province where unique parallels occur, some only on metalwork. A primary milieu is proposed for the Kilduncan slab in a context of Scando-insular culture in Northern Scotland, probably on proto-episcopal estates in Moray linked with St Andrews but drawing on cultural affinities on occasion as distant as south-west Wales and Southern Ireland, transmitted via western sea routes to a lively Christian culture in northern Scotland before redistribution southwards. Unexpected connections also occur with north-east England, implying St Andrews influence at work during Alban expansion southwards around the end of the first millennium AD. INTRODUCTION Ireland and England in the period of Viking and Norse activity is here augmented with the epithet The discovery in 2001 (Dundee Courier 5 Albano-Norse to describe Scotland during this September 2002, illus; DES 2002, 161; Speirs period (and Scando-Manx for the Isle of Man), 2003a, 24–5; 2003b, 4–7) of a substantial frag- and all are set within an overarching concept of ment of highly decorated sculpture at Kilduncan, Scando-insular art within which they are local Fife, provides a useful opportunity to study manifestations. -

Helen C. Rawson Phd Thesis

><1.=?<1= 92 >41 ?85@1<=5>C+ .8 1B.758.>598 92 >41 5018>525/.>598! ;<1=18>.>598 .80 <1=;98=1= >9 .<>12./>= 92 =538525/.8/1 .> >41 ?85@1<=5>C 92 => .80<1A=! 2<97 &)&% >9 >41 750"&*>4 /18>?<C, A5>4 .8 .005>598.6 /98=501<.>598 92 >41 01@169;718> 92 >41 ;9<><.5> /9661/>598 >9 >41 1.<6C '&=> /18>?<C 4HNHP /# <DXTQP . >KHTLT =VEOLUUHG IQS UKH 0HJSHH QI ;K0 DU UKH ?PLWHSTLUZ QI =U .PGSHXT '%&% 2VNN OHUDGDUD IQS UKLT LUHO LT DWDLNDENH LP <HTHDSFK-=U.PGSHXT+2VNN>HYU DU+ KUUR+$$SHTHDSFK"SHRQTLUQSZ#TU"DPGSHXT#DF#VM$ ;NHDTH VTH UKLT LGHPULILHS UQ FLUH QS NLPM UQ UKLT LUHO+ KUUR+$$KGN#KDPGNH#PHU$&%%'($**% >KLT LUHO LT RSQUHFUHG EZ QSLJLPDN FQRZSLJKU Treasures of the University: an examination of the identification, presentation and responses to artefacts of significance at the University of St Andrews, from 1410 to the mid-19th century; with an additional consideration of the development of the portrait collection to the early 21st century Helen Caroline Rawson Submitted in application for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Art History, University of St Andrews, 20 January 2010 I, Helen Caroline Rawson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 111,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2001 and as a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in June 2003; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2001 and 2010. -

ANCIENT LIVES Ancient Lives Provides New Perspectives on Object, People and Place in Early Scotland and Beyond

Sheridan (eds) Sheridan and Hunter ANCIENT ANCIENT ANCIENT LIVES Ancient Lives provides new perspectives on object, people and place in early Scotland and beyond. The 19 papers cover topics ranging from the Neolithic to the Medieval period, and from modern museum practice to ancient craft skills. The material culture of ancient lives is centre stage – how it was created and used, how it was rediscovered and thought about, and how it is displayed. Dedicated to Professor David V Clarke, former Keeper of Archaeology in National Museums Scotland, on his 70th birthday, the book comprises three sections which reflect some of his many interests. “Presenting the past” offers perspectives on current museum LIVES practice, especially in relation to archaeological displays. “Ancient lives and multiple lives” looks at antiquarian approaches to the Scottish past and the work of a Scottish antiquary abroad, while “Pieces of the past” offers a series of authoritative case-studies on Scottish artefacts, as well as papers on the iconic site of Skara Brae and on the impact of the Roman world on Scotland. With subjects ranging from Gordon Childe to the Govan Stones ANCIENT LIVES and from gaming pieces to Grooved Ware, this scholarly and OBJECT, PEOPLE AND PLACE IN EARLY SCOTLAND. accessible volume provides a show-case of new information and new perspectives on material culture linked, but not limited to, Scotland. ESSAYS FOR DAVID V CLARKE ON HIS 70TH BIRTHDAY Sidestone edited by ISidestoneSBN 978-90-8890-375-5 Press ISBN: 978-90-8890-375-5 Fraser Hunter and Alison Sheridan 9 789088 903755 This is an Open Access publication.