Helen C. Rawson Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956)

099-105dnh 10 Clark Watson collection_baj gs 28/09/2015 15:10 Page 101 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XVI, No. 2 The art collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956) Adrian Clark 9 The co-author of a ously been assembled. Generally speaking, he only collected new the work of non-British artists until the War, when circum- biography of Peter stances forced him to live in London for a prolonged period and Watson identifies the he became familiar with the contemporary British art world. works of art in his collection: Adrian The Russian émigré artist Pavel Tchelitchev was one of the Clark and Jeremy first artists whose works Watson began to collect, buying a Dronfield, Peter picture by him at an exhibition in London as early as July Watson, Queer Saint. 193210 (when Watson was twenty-three).11 Then in February The cultured life of and March 1933 Watson bought pictures by him from Tooth’s Peter Watson who 12 shook 20th-century in London. Having lived in Paris for considerable periods in art and shocked high the second half of the 1930s and got to know the contempo- society, John Blake rary French art scene, Watson left Paris for London at the start Publishing Ltd, of the War and subsequently dispatched to America for safe- pp415, £25 13 ISBN 978-1784186005 keeping Picasso’s La Femme Lisant of 1934. The picture came under the control of his boyfriend Denham Fouts.14 eter Watson According to Isherwood’s thinly veiled fictional account,15 (1908–1956) Fouts sold the picture to someone he met at a party for was of consid- P $9,500.16 Watson took with him few, if any, pictures from Paris erable cultural to London and he left a Romanian friend, Sherban Sidery, to significance in the look after his empty flat at 44 rue du Bac in the VIIe mid-20th-century art arrondissement. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection MC.100

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection MC.100 Last updated on January 06, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 110.American poets................................................................................................................................. 9 115.British poets.................................................................................................................................... 16 120.Dramatists........................................................................................................................................23 130.American prose writers...................................................................................................................25 135.British Prose Writers...................................................................................................................... 33 140.American -

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

0-208 Artwork

The North*s Original Free Arts Newspaper + www.artwork.co.uk Number 208 Pick up your own FREE copy and find out what’s really happening in the arts May - June 2019 Shedding Old Coats – one of the haunting works by Karólína Lárusdóttir from a recent exhibition of her work at the Castle Gallery, Inverness. In- side: Denise Wilson tells the story of this Anglo-Icelandic artist. INSIDE: Cultivating Patrick Geddes :: Tapestry Now Victoria Crowe at City Arts :: A northern take on Turner artWORK 208 May/June 2019 Page 2 artWORK 208 May/June 2019 Page 3 CASTLE GALLERY KELSO POTTERY 100 metresmetres behind behind the Kelso Kelso Abbey in the Knowes Car Park. Abbey in The Knowes Car Park. Mugs, jugs, bowls and “TimePorridge Tablets” and Soup fired Bowls, in Piggy theBanks Kelso and Goblets,Pit Kiln. Ovenproof OpenGratin DishesTuesday & Pit-fi to Saturday red Pieces. Open Mon, 10 Braemar Road, 10am-1pm and 2pm-5pm Ballater Thurs, Fri and TelephoneOpen Tues -(01573) Sat 10 to224027 1 - 2 to 5 Sat 10.00 -5.00 AB35 5RL NEWTelephone: SHOP, (01573) DISABLED 224027 ACCESS larksgallery.com facebook/Larks Gallery 013397 55888 CHECK OUT OUR ROBERT GREENHALF OTHER TITLES opening 17th may Jane B. Gibson RMS Wild Wings Over Lonely Shores Scotland’s Premier artWORK kirsty lorenz richard bracken 7th - 29th June www.artwork.co.uk Miniture Portrait Oils and woodcuts inspired by the birds of our jim wright kirstie cohen Painter coast and wetlands by Robert Greenhalf SWLA with hand-carved birds by Michael Lythgoe. West Highland www.resipolestudios.co.uk Open Studio/Gallery Castle Gallery, 43 Castle St, Inverness, IV2 3DU 01463 729512 Wayfarer loch sunart | acharacle | argyll | scotland | ph36 4hx EVERY FRIDAY [email protected] www.westhighlandwayfarer.co.uk or by appointment any www.castlegallery.co.uk THE other time. -

The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 2007, 'The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair' Edinburgh Law Review, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 300-48. DOI: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Edinburgh Law Review Publisher Rights Statement: ©Cairns, J. (2007). The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair. Edinburgh Law Review, 11, 300-48doi: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 EdinLR Vol 11 pp 300-348 The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: the Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair John W Cairns* A. -

2016-2017 Court Minutes

Minutes 2016-2017 No 1 1 UNIVERSITY COURT OF ST ANDREWS AT ST ANDREWS on the 14th day of OCTOBER 2016 AT A MEETING OF THE COURT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS Present: Ms Catherine Stihler, Rector (President) ; Dame Anne Pringle, Senior Governor; Professor Sally Mapstone, Principal; Professor Garry Taylor, Deputy Principal & Master of the United College; Mr Adrian Greer, Chancellor’s Assessor; Ms Charlotte Andrew, President, Students' Association; Mr Jack Carr, Director of Representation, Students' Association; Mr Dylan Bruce, Rector’s Assessor; Mr Nigel Christie and Mr Kenneth Cochran, General Council Assessors; Professor Frances Andrews, Dr Chris Hooley, Professor James Naismith and Dr Philip Roscoe, Senate Assessors; Mr David Stutchfield, Non-Academic Staff Assessor; Councillor Bryan Poole, Provost of Fife’s Assessor; Mr Timothy Allan, Ms Pamela Chesters, Mr Ken Dalton, Professor Stuart Monro, Mr Nigel Morecroft, Dr Mary Popple and Professor Sir David Wallace, Non-Executive Members. In attendance: Professor Verity Brown, Vice-Principal (Enterprise & Engagement); Mr Alastair Merrill, Vice-Principal (Governance & Planning); Professor Lorna Milne, Vice- Principal (Proctor); Dr Anne Mullen, Vice-Principal (International); Mr Derek Watson, Quaestor & Factor; Professor Derek Woollins, Vice-Principal (Research); Mr Andy Goor, Finance Director; Dr Gillian MacIntosh, Executive Officer to the University Court. I. SESSION ON BREXIT Prior to the formal Court meeting, members held a strategic discussion session to discuss the potential implications of Brexit on the University and the UK HE sector in general (report on file, Court 16/22). II. OPENING BUSINESS 1. WELCOME The Rector welcomed Professor Sally Mapstone, Mr Adrian Greer, Ms Pamela Chesters, Mr Dylan Bruce, Ms Charlotte Andrew and Mr Jack Carr, who were each attending their first formal meeting of Court as a new members. -

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series: Stirling Produced from Information Contained Within The Gazetteer for Scotland. Tourist Guide of Stirling Index of Pages Introduction to the settlement of Stirling p.3 Features of interest in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.5 Tourist attractions in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.9 Towns near Stirling p.15 Famous people related to Stirling p.18 Further readings p.26 This tourist guide is produced from The Gazetteer for Scotland http://www.scottish-places.info It contains information centred on the settlement of Stirling, including tourist attractions, features of interest, historical events and famous people associated with the settlement. Reproduction of this content is strictly prohibited without the consent of the authors ©The Editors of The Gazetteer for Scotland, 2011. Maps contain Ordnance Survey data provided by EDINA ©Crown Copyright and Database Right, 2011. Introduction to the city of Stirling 3 Scotland's sixth city which is the largest settlement and the administrative centre of Stirling Council Area, Stirling lies between the River Forth and the prominent 122m Settlement Information (400 feet) high crag on top of which sits Stirling Castle. Situated midway between the east and west coasts of Scotland at the lowest crossing point on the River Forth, Settlement Type: city it was for long a place of great strategic significance. To hold Stirling was to hold Scotland. Population: 32673 (2001) Tourist Rating: In 843 Kenneth Macalpine defeated the Picts near Cambuskenneth; in 1297 William Wallace defeated the National Grid: NS 795 936 English at Stirling Bridge and in June 1314 Robert the Bruce routed the English army of Edward II at Stirling Latitude: 56.12°N Bannockburn. -

A Memorial Volume of St. Andrews University In

DUPLICATE FROM THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND. GIFT OF VOTIVA TABELLA H H H The Coats of Arms belong respectively to Alexander Stewart, natural son James Kennedy, Bishop of St of James IV, Archbishop of St Andrews 1440-1465, founder Andrews 1509-1513, and John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews of St Salvator's College 1482-1522, cofounders of 1450 St Leonard's College 1512 The University- James Beaton, Archbishop of St Sir George Washington Andrews 1 522-1 539, who com- Baxter, menced the foundation of St grand-nephew and representative Mary's College 1537; Cardinal of Miss Mary Ann Baxter of David Beaton, Archbishop 1539- Balgavies, who founded 1546, who continued his brother's work, and John Hamilton, Arch- University College bishop 1 546-1 57 1, who com- Dundee in pleted the foundation 1880 1553 VOTIVA TABELLA A MEMORIAL VOLUME OF ST ANDREWS UNIVERSITY IN CONNECTION WITH ITS QUINCENTENARY FESTIVAL MDCCCCXI MCCCCXI iLVal Quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis Horace PRINTED FOR THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND COMPANY LIMITED MCMXI GIF [ Presented by the University PREFACE This volume is intended primarily as a book of information about St Andrews University, to be placed in the hands of the distinguished guests who are coming from many lands to take part in our Quincentenary festival. It is accordingly in the main historical. In Part I the story is told of the beginning of the University and of its Colleges. Here it will be seen that the University was the work in the first instance of Churchmen unselfishly devoted to the improvement of their country, and manifesting by their acts that deep interest in education which long, before John Knox was born, lay in the heart of Scotland. -

The Art of Picture Making 5 - 29 March 2014

(1926-1998) the art of picture making 5 - 29 march 2014 16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6HZ tel 0131 558 1200 email [email protected] www.scottish-gallery.co.uk Cover: Paola, Owl and Doll, 1962, oil on canvas, 63 x 76 cms (Cat. No. 29) Left: Self Portrait, 1965, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 73 cms (Cat. No. 33) 2 | DAVID McCLURE THE ART OF PICTURE MAKING | 3 FOREWORD McClure had his first one-man show with The “The morose characteristics by which we Scottish Gallery in 1957 and the succeeding recognise ourselves… have no place in our decade saw regular exhibitions of his work. painting which is traditionally gay and life- He was included in the important surveys of enhancing.” Towards the end of his exhibiting contemporary Scottish art which began to life Teddy Gage reviewing his show of 1994 define The Edinburgh School throughout the celebrates his best qualities in the tradition 1960s, and culminated in his Edinburgh Festival of Gillies, Redpath and Maxwell but in show at The Gallery in 1969. But he was, even by particular admires the qualities of his recent 1957 (after a year painting in Florence and Sicily) Sutherland paintings: “the bays and inlets where in Dundee, alongside his great friend Alberto translucent seas flood over white shores.” We Morrocco, applying the rigour and inspiration can see McClure today, fifteen years or so after that made Duncan of Jordanstone a bastion his passing, as a distinctive figure that made a of painting. His friend George Mackie writing vital contribution in the mainstream of Scottish for the 1969 catalogue saw him working in a painting, as an individual with great gifts, continental tradition (as well as a “west coast intellect and curiosity about nature, people and Scot living on the east coast whose blood is part ideas. -

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

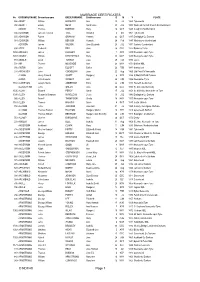

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Buyer Profile: Forthcoming, Current & Awarded Tender Exercises

Procurement PROCUREMENT BUYER PROFILE The majority of tenders for The University of St Andrews are now administered through our E-tendering system. Please go to our tender web site at: https://in-tendhost.co.uk/universityofstandrews/ If you experience problems in registering at the above address, please do not hesitate to contact the Procurement Team on the contact details at the foot of the page. As well as the Buyer Profile, the University currently advertises tenders on: • Public Contracts Scotland - http://www.publiccontractsscotland.gov.uk/ • OJEU (Official Journal of the European Union) FORTHCOMING, CURRENT & AWARDED TENDER EXERCISES Blue Shading = Current and Unawarded Tenders Title Date of OJEU / Notice Deadline Closing Date Date Contract OJEU Award Appearance in Reference for for Receipt of Awarded Awarded To Reference No. OJEU / Public Contracts Requesting Tenders @ 12 Scotland Docs @ noon 12noon Estates: Dismantling & N/A EST/300921/KR/SL N/A 22-OCT-21 Demolition of the Miller Shed, Eden Campus Page 1 of 149 Ref: X:\Procurement\shared\#Document Library 2\#Tender\buyer_profile.docx \ 30-Sep-21 Walter Bower House, Eden Campus, Main Street, Guardbridge, Fife, KY16 0US T: +44 (0)1334 462523 E: [email protected] The University of St Andrews is a charity registered in Scotland, No: SC013532 Procurement Entrepreneurial St Andrews 06-SEP-21 ESA/060921/CZ/SL 08-OCT-21 08-OCT-21 Unit: IP Renewal Services Publications: Print Tender for N/A PUB/100921/CC/SL N/A 01-OCT-21 Undergraduate Prospectus 2023 & 2024 Entries (mini-Tender