Study of the Sales-To-Delivery Process for Complete Buses and Coaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Contents 1. Message from the General Director 2. 2019: A Record Year 3. A Year of Celebrations and Important Milestones 4. At the forefront of technology 5. Irizar Group Sustainability Message from the General Director In March, when the global pandemic was declared, an enormous health crisis of unknown dimensions was confirmed and that lead to an unprecedented economic crisis. We have been working on staying close to our customers these months and ensuring that the people in the Group can keep doing their jobs safely and maintain their delicate work life balance. Likewise, we have given some social support, in accordance with our principles and mission. I am very proud of the behaviour of every person in the Group and the attitude of union and solidarity with which we are facing these difficult times. However, this annual report for 2019 should let us recognise the goal we are aspiring to. 2019 was the year we celebrated the 130th anniversary of Irizar. It has also been ten years since we had our own stand at the Busworld fair for the first time. And we are celebrating the 20th anniversary of Irizar Mexico, the 10th anniversary of Datik and it has been ten years since we became a manufacturer of integral coaches. The Group currently has 13 production plants, 8 brands of its own, an R&D centre and 8 distribution and Without a doubt, the success of the Group is an outcome of the strategy based on brand, technology and after-sales companies. We have activities in six different sectors, including passenger transport, electro-mo- sustainability. -

Test Facility Capabilities

MCC Mobile Climate Control Military MCC Mobile Climate Control On Road MCC Mobile Climate Control Off Road MCC Mobile Climate Control Specialty Vehicles MCC Mobile Climate Control Test Facility Test Facility Capabilities Mobile Climate Control Test Facility, Toronto A new dimension in testing Something all of these vehicles have in common is an Since 1975 MCC has been involved in the testing and HVAC system designed and manufactured for function, validation of HVAC products and systems for transit, reliability and longevity. We welcome the challenge and we off-road, utility, military, and specialty applications. surpass every expectation. With our sophisticated and flexible test chambers and analysis equipment, we are able to quantify performance, robustness, and reliability of all types of equipment, in Technology and all types of conditions. MCC has invested significantly in equipment, but MCC’s greatest asset is its’ people. State of the art test facilities MCC’s research & development testing facilities include expertise extensive equipment for testing the performance of HVAC systems as well as components within the systems. Our custom-built climate chamber, the core of our test Transit bus in Large Chamber ready for A/C system test. facility, enables MCC to provide a chamber with a large internal volume capable of accepting large articles. In our climate chamber, we are able simulate the most at your side, severe environmental conditions and put client vehicles or HVAC systems through the most demanding tests. In addition to the specifications of the state of the art test facility, the IP-cameras in the drive in chamber can be accessed from anywhere, improving the ability to remotely when you need it! & securely, view ongoing tests. -

Irizar Technology Page 6

Nº 7 October 2013 - Irizar Group Magazine Irizar technology Page 6 CREATIO R&D Centre Page 4 Euro VI The new generation Page 8 Datik Intelligent information systems Page 29 People Alain Flausch Secretary General UITP Page 10 >> Table of Contents 4| Front cover – Technology Creatio – The Irizar Group’s Research and Development Centre IEB: Irizar’s electric bus, full speed ahead EURO VI: New generation of Irizar brand complete buses 10| Interview with Alain Flausch, Secretary General UITP 14| Markets Irizar, the leading brand in the United Kingdom Long distance coaches A small yet great Irizar i6 22| Irizar Group Irizar Mexico: a project in continuous expansion Irizar Brasil: focused on exporting Morocco: platform for Europe 27| Diversification Jema in the JT60SA research project in Japan Datik: The fatigue detector and Ecoassits: Driving efficiency and sustainable mobility Masats arrives in the USA Hispacold launches a range of electric acclimatising systems 34| Innovation The Irizar i3 arrives in Europe 36| CSR Joining the Global Compact 38| On the road Australia – The island continent 47| Rear-view Serene maturity: 1990 – 2000 (I) People & Coaches // October 2013 >> EDITORIAL Together we form a strong team research and technological development. Its duty is to work on innovation with a long-term vision, focusing on improving the Group’s sustainable competitiveness in the future as well as its employment and wealth generating growth in the areas where we operate. The strongest research efforts are focused on our bodywork components for conventional buses as well as on all the systems in our range of complete buses. -

Adressverzeichnis

ADRESSVERZEICHNIS ANHÄNGER & AUFBAUTEN . .Seite 11–13 BUSSE. .Seite 13–16 LKW und TRANSPORTER . .Seite 16–19 SPEZIALFAHRZEUGE . .Seite 19–22 ANHÄNGER & Aebi Schmidt ALF Fahrzeugbau Andreoli Rimorchi S.r.l. Deutschland GmbH GmbH & Co.KG Via dell‘industria 17 AUFBAUTEN Albtalstraße 36 Gewerbehof 12 37060, Buttapietra (Verona) 79837 St. Blasien 59368 Werne ITALIEN Acerbi Veicoli Industriali S.p.A. Tel. +49.7672-412-0 Tel. +49.2389 98 48-0 Tel. +39 045 666 02 44 Strada per Pontecurone, 7 www.aebi-schmidt.com www.alf-fahrzeugbau.de www.andreoli-ribaltabili.it 15053 Castelnuovo Scrivia (AL) ITALIEN Agados spol. s.r.o. ALHU Fahrzeugtechnik GmbH Andres www.acerbi.it Rumyslová 2081 Borstelweg 22 Hermann Andres AG 59401 Velké Mezirici 25436 Tornesch Industriering 42 Achleitner Fahrzeugbau TSCHECHIEN Tel. +49.4122 - 90 67 00 3250 Lyss Innsbrucker Straße 94 Tel. +420 566 653 311 www.alhu.de SCHWEIZ 6300 Wörgl www.agados.cz Tel. +41 32 387 31 61 Asch- ÖSTERREICH AL-KO www.andres-lyss.ch wege & Tönjes Aucar- Tel. +43 5332-7811-0 Agados Anhänger Handels Alois Kober GmbH Zur Schlagge 17 Trailer SL www.achleitner.com GmbH Ichenhauser Str. 14 Annaburger Nutzfahrzeuge 49681 Garrel Pintor Pau Roig 41 2-3 Schwedter Str. 20a 89359 Kötz GmbH Tel. +49.4474-8900-0 08330 Premià de mar, Barcelona Ackermann Aufbauten & 16287 Schöneberg Tel. +49.8221-97-449 Torgauer Straße 2 www.aschwege-toenjes.de SPANIEN Fahrzeugvertrieb GmbH Tel. +49.33335 42811 www.al-ko.de 06925 Annaburg Tel. +34 93 752 42 82 Am Wallersteig 4 www.agados.de Tel. +49.35385-709-0 ASM – Equipamentos www.aucartrailer.com 87700 Memmingen-Steinheim Altinordu Trailer www.annaburger.de de Transporte, S Tel. -

An Analysis of the UK Coach Market This Report Is Published by the Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership 3 Birdcage Walk, London, SW1H 9JJ

An Analysis of the UK Coach Market This report is published by the Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership 3 Birdcage Walk, London, SW1H 9JJ Tel: +44 (0)20 7304 6880 E-mail: [email protected] Author: Daniel Hayes, Project Manager Reviewed by: Gloria Esposito, Head of Projects Date of Report: 1st September 2020 LowCVP would like to thank members of their Bus & Coach Working Group and other contributors for providing supporting information contained within this report – Confederation of Passenger Transport, Yutong, National Express, Johnson Coaches, Irizar UK, Luckett’s Travel, SMMT, Volvo Group UK, Scania GB, Evobus. An Analysis of the UK Coach Market 3 Contents Executive Summary 4 Glossary 5 1.0 Introduction 6 1.1 Estimating UK Coach Fleet Size 7 1.2 Annual New Coach Registrations 10 1.3 Coach Manufacturers 13 1.4 Travel Statistics 16 1.5 Coach Operators 16 2.0 Greenhouse Gas Emissions 18 2.1 Introduction to UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions 19 2.2 Estimating Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Coach Operations 22 3.0 Air Quality Emissions 26 3.1 UK Coach Fleet: Euro Standards breakdown 28 3.2 NOx and PM emissions 30 3.3 Coach Retrofit 31 4.0 Conclusion 32 5.0 References 34 An Analysis of the UK Coach Market 4 Executive Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected the UK The coach industry is smaller than other heavy-duty markets coach industry during what would normally be the busiest such as bus and trucks but plays a vital role in providing time of year. -

DRIVING PROGRAMS for ZERO EMISSION TRANSIT Umberto Guida UITP - Director Research and Innovation

DRIVING PROGRAMS FOR ZERO EMISSION TRANSIT Umberto Guida UITP - Director Research and Innovation THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF PUBLIC TRANSPORT UITP is… UITP main ac=vies 1,400 company-members in 96 Countries ü PT Operators Advocacy & Outreach ü PT Authorities & Cities ü Industries et supply industry Knowledge ü Decision Makers ü Scientific & research institutes, Network & Business consultancies UITP worldwide organisaon with 15 regional Offices UITP through its Secretary General is one of the 12 members of High-level Advisory Group on Sustainable Transport set by United Naons Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon UITP’s members commitment = -40% emissions by 2025 2 350 climate actions / 30% on Buses DECARBONISING PUBLIC TRANSPORT Quality of life of citizens ensuring Accessible, Comfortable, Cleaner Vehicles Quality of service to passengers Improved commercial speed PT Dedicated Infrastructure Traffic & operations management Efficient Combined mobility Smart use of energy in vehicles Modal shift Renewal of old-bus fleets towards low/ zero emission plus Modal Shift for a multiplier effect 3 EVOLUTION OF FLEETS Which propulsion technology / solution? Current fleet Future fleet Bus fleet breakdown per fuel or energy used + 41,5% Respondents distribution according to 5 future plans to change propulsion system ratio ZEEUS: A PROJECT TO SUPPORT ELECTRIC BUS DEPLOYMENT 40 Consortium Partners 20 User Group Members 10 demo cities 50 Observatory Members 22,5 million€ ~70 electric buses Coordinator: UITP EU funding: 13,5 60 observed cities million € 300 -

2011 Parciales Y Wvta.Xlsx

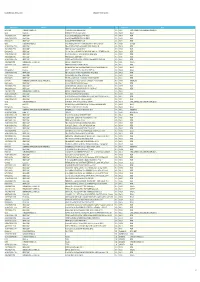

Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo Homologaciones Parciales y WVTA 2011 Nº Homologación Fabricante Tipo ST Nº Informe ST Marcas E9 66R-018469 CARROCERA CASTROSUA, S.A. CS-40 MAGNUS L-10,750 s/ MAN B.2007.46.003 INSIA 11IA0861 CARSA; CASTROSUA CARSA; CARROCERA CASTROSUA, S.A. 022113 BEULAS, S.A. R107-Man-B.2007.46.002-Glory-2 pisos bast. MAN INSIA 11IA0874 BEULAS e9*97/27*2003/19*2158*05 IRIZAR S. COOP. i62 var. i621335 bast. MERCEDES BENZ 634 01 o HTAE 05 INSIA 11IA0877 IRIZAR e9*2001/85*2001/85*2169*05 IRIZAR S. COOP. i62 var. i621335 bast. MERCEDES BENZ 634 01 o HTAE 05 INSIA 11IA0878 IRIZAR E9 66R-018452 Ext. II IRIZAR S. COOP. i6-13,35 s/ MERCEDES BENZ HTAE 05 o 634 01 INSIA 11IA0906 IRIZAR 002146 CALDERERIA DE PABLOS, S.A. NPR75 chasis ISUZU, NPR75 var. NPR75HSM d.c. ISUZU NPR75-V cisterna HIDROCAR-215 INSIA 11IA0926 DE PABLOS e9*2001/85*2001/85*2177*10 IRIZAR S. COOP. PB3 var. PB31537R d.c. PB 15.37 bast. SCANIA M335, 13B6X2E, 9B6X2E d.c. ..EB.. INSIA 11IA0948 IRIZAR e9*97/27*2003/19*2166*10 IRIZAR S. COOP. PB3 M335 var. PB31537R K6X2 EB d.c. PB 15.37 INSIA 11IA0947 IRIZAR E9 66R-008318 Ext. II IRIZAR S. COOP. Century var. NCentury 12.85 s/ MAN R33 D26, R33 D20, B.2007.46.001 d.c. 18.??0 RATIO/EEV, 18.xxx HOC INSIA 11IA0888 IRIZAR e9*2001/85*2001/85*2154*13 IRIZAR S. COOP. i62 var. -

Irizar Technology Page 6

Nº 7 October 2013 - Irizar Group Magazine Irizar technology Page 6 CREATIO R&D Centre Page 4 Euro VI The new generation Page 8 Datik Intelligent information systems Page 29 People Alain Flausch Secretary General UITP Page 10 >> Table of Contents 4| Front cover – Technology Creatio – The Irizar Group’s Research and Development Centre IEB: Irizar’s electric bus, full speed ahead EURO VI: New generation of Irizar brand complete buses 10| Interview with Alain Flausch, Secretary General UITP 14| Markets Irizar, the leading brand in the United Kingdom Long distance coaches A small yet great Irizar i6 22| Irizar Group Irizar Mexico: a project in continuous expansion Irizar Brasil: focused on exporting Morocco: platform for Europe 27| Diversification Jema in the JT60SA research project in Japan Datik: The fatigue detector and Ecoassits: Driving efficiency and sustainable mobility Masats arrives in the USA Hispacold launches a range of electric acclimatising systems 34| Innovation The Irizar i3 arrives in Europe 36| CSR Joining the Global Compact 38| On the road Australia – The island continent 47| Rear-view Serene maturity: 1990 – 2000 (I) People & Coaches // October 2013 >> EDITORIAL Together we form a strong team research and technological development. Its duty is to work on innovation with a long-term vision, focusing on improving the Group’s sustainable competitiveness in the future as well as its employment and wealth generating growth in the areas where we operate. The strongest research efforts are focused on our bodywork components for conventional buses as well as on all the systems in our range of complete buses. -

Peoplecoaches-2012-EN.Pdf

>> Summary 4| Front cover > Irizar presents its new brand image at the Fiaa > Irizar continues to establish its integral design coach in Europe 12| Interview with... > Wolfgang Steinbrück, President of BDO – Germany 16| Irizar Group > The Irizar i6 in Brazil and other South American countries > Launch of the Irizar i6 in Australia > Launch of the Irizar i6 in South Africa > Jema opens its first subsidiary in the United States > Interview: Iñigo Odriozola and Iñigo Etxabe (Datik) > Irizar Mexico: a promising future 28| Customers > Irizar coaches at the London Olympic Games > Redwing Coaches. A Premium Service from Irizar > Irizar accompanies the Pope’s visit to Leon (Mexico) > Luxury Irizar coaches travel through the Baltic States > Ultramar Transport. Trusting in Irizar for more than a decade > Plana expands its fleet with Irizar > Interview with Manuel Torres > Africa Cup of Nations in Gabon 42| Innovation > Commitment to passenger accessibility and mobility > Improve efficiency, safety and confort 46| Corporate Social Responsability > A green future: the electric city bus by Irizar 48| Events > International fairs 52| Products Range > Launch of the Irizar i3 54| Vips > Argos Shimano with new Irizar coach > Luxury coaches in Mexico 57| Short News... > Agreement between Irizar and Tecnun > Irizar and Caja Rural Agreement 58| On the road... > Around Brazil 68| Rear-view > The unstable youth (1990-2000) People & Coaches // October 2012 >> EDITORIAL “SOLIDITY AND GROWTH” year we have sold more than 100 units that are circulating in seven countries. Our Group, which had a record turnover of 500 million euros in 2011, will be capable of maintaining this record this year, despite the crisis intensifying in Europe, particularly in the peripheral countries. -

Butaca Irizar PB

Catálogo general de componentes y recambios de autobuses y autocares 2014 · 2015 ÍNDICE 01 · Iluminación 2 02 · Embellecedores 35 03 · Carrocería 44 04 · Interiores 70 05 · Espejos 116 06 · Audio, vídeo y eléctrico 141 07 · Climatización 178 08 · Puertas y neumática 197 ILUMINACIÓN Faros individuales Faros microbús Faros de niebla DRL Cristales Reflectores Pilotos intermitentes Pilotos de baliza Pilotos de gálibo 3ª luz de stop Pilotos modulares Pilotos específicos Pilotos microbús Tulipas Portalámparas Pilotos de matrícula Catadriópticos ILUMINACIÓN · FAROS INDIVIDUALES Faro xenón 24 V. Beulas Stergo, Eurostar y Neoplan Starliner I. Faro. Ref. 1100700001 Cruce DE-H1 con soporte y regulador. Ref. 1100700004 Largas DE-H1 con soporte. Ref. 1100700005 Niebla.DE-H1 con soporte. Ref. 1100700006 Capuchón. Ref. 1000700007 Faro cruce H1. Equipan: Ovi, Sunsundegui, Castrosua, Ayats, Beulas, Faro largas H1. Equipan: Ovi, Sunsundegui, Castrosua, Ayats, Beulas, Irizar, Andecar, Ferqui, Ugarte y Caetano. Irizar, Andecar, Ferqui, Ugarte y Caetano. Ref. 1101200002 Ref. 1101200008 C/soporte. Ref. 1101200003 C/soporte. Ref. 1101200009 C/posición. Ref. 1101200010 C/posición y soporte. Ref. 1101200011 Faro largas H1. Equipan: Ovi, Sunsundegui, Castrosua, Ayats, Beulas, Faro universal largas y posición. Equipa Sunsundegui y Noge. Irizar, Andecar, Ferqui, Ugarte y Caetano. Ref. 1101201233 Ref. 1101200012 C/soporte. Ref. 1101200013 Faro cruce 50 mm. Equipa Tata Hispano Divo, Carsa Master 36 Beulas Faro largas Equipa Tata Hispano Divo, Carsa Master 36 Beulas Glory Glory y Jewel. y Jewel. Xenón. Ref. 1100700024 Xenón. Ref. 1100700025 H7. Ref. 1100700026 H7. Ref. 1100700942 3 ILUMINACIÓN · FAROS INDIVIDUALES Faro cruce. Equipan: Ayats, Barbi, Beulas, Bova, Caetano, Carsa, Faro largas. Equipan: Ayats, Barbi, Beulas, Bova, Caetano, Carsa, Castrosua, Ferqui, Jonckheere, Marcopolo, Noge, Neoplan, Obradors, Castrosua, Ferqui, Jonckheere, Marcopolo, Noge, Neoplan, Obradors, Sunsundegui, Unvi, Tata Hispano, Temsa, Vanhool. -

No. Regist Name Built Year O Year O Scrapp Other

No. Regist Name Built Year O Year O Scrapp Other 283 8916 CYH Andecar Viana ? 2006 ? EuroRider C35SRi. 618 PM-4765-BZ Irizar Century ? 2003 ? Scania K113CLB 293 PM-5317-BP MAN 16.372 HOCL / Noge Gregal ? ? ? 414 8889 CCR MAN 18.420 HOCL / Noge Touring Star? I 2006 ? 623 PM-2100-BV Pegaso 5232 / Beulas Stergo ? 2003 ? 278 PM-8612-BU Irizar Century ? 2012 ? Scania K113CLC 121 IB5236BP MAN 11.190 HOCL / Beulas Midistar ? 2002 ? 409 PM-2068-BM MAN 16.372 HOCL / Noge Gregal ? 2003 ? NMD-958 Irizar Century II ? ? 2015 290 PM-1767-BU Beulas Jewel ? 2003 ? MAN 16.372 Beulas Jewel Space- 217 PM-9549-AM Setra S215 H 1987 2003 ? 218 PM-9550-AM Setra S215 H 1987 2003 ? 219 PM-6126-AY Setra S212 HD 1989 2003 2010 PM-2600-BC Setra S215 HD 1990 2003 ? 249 PM-7443-BD Beulas Eurostar ´E 1990 2003 ? MAN 16.360 Beulas Eurostar E92 703 PM-2602-BC Setra S215 HD 1990 2003 ? 161 M-6057-NN Ayats Olimpo B 1992 2004 ? 546 C-0015-BB Ayats Olimpo B 1992 2003 ? 260 KTV-560 Scania K113CLA / Irizar Century 12.351992 2003 2008 516 PM-7636-BV Beulas Jewel 1994 2003 ? MAN 22.370 621 PM-6254-CB Irizar Century 1995 2003 2013 Iveco EuroRider C29 352 PM-3419-BZ Irizar Century 1995 2007 ? Scania K113CLB 709 PM-8828-BZ Scania L113CLL / Hispano VOV 1995 ? ? PM-8551-BZ Iveco EuroRider C35 / Ayats Atlas 1995 2003 723 IB 6249 CY Volvo B10M / Ugarte U2000 1998 2005 2008 11/08/1998 248 PM-9788-BZ Scania K113CLB / Irizar Century II 12.371998 2003 647 IB-8664-CV Irisbus EuroRider 397E.12.35 / Irizar Century1998 II 2003 2013 501 IB-0722-CW MAN 18.350 HOCL / Irizar Century 1998 2003 -

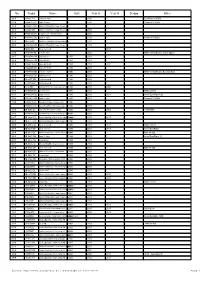

P&A Plants A4 2013 by MANUFACTURER Web

AUTOMOBILE ASSEMBLY & ENGINE PRODUCTION PLANTS IN EUROPE BY MANUFACTURER Type produced Plant location Manufacturer Brand Engine PC LCV CV Bus ACEA MEMBERS BMW GROUP AT-Austria Steyr BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Dingolfing BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Leipzig BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Munich BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Regensburg BMW GROUP BMW UK-United Kingdom Cowley (Oxford) BMW GROUP Mini UK-United Kingdom Goodwood BMW GROUP Rolls Royce UK-United Kingdom Hams Hall BMW GROUP Facilities not owned / operated by BMW AT-Austria Graz BMW GROUP Mini at MAGNA STEYR plant NL-Netherlands Born BMW GROUP Mini at VDL plant (from 2014) RU-Russia Kaliningrad BMW GROUP BMW at AVTOTOR plant DAF TRUCKS NV BE-Belgium Westerlo DAF TRUCKS NV DAF NL-Netherlands Eindhoven DAF TRUCKS NV DAF UK-United Kingdom Leyland DAF TRUCKS NV DAF DAIMLER AG DE-Germany Affalterbach DAIMLER AG AMG DE-Germany Berlin DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Bremen DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Dortmund DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz minibuses DE-Germany Düsseldorf DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, for VOLKSWAGEN DE-Germany Kölleda DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Ludwigsfelde DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, for VOLKSWAGEN DE-Germany Mannheim DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz (truck engines), Setra (JV KAMAZ) DE-Germany Neu-Ulm DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Rastatt DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Sindelfingen DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Untertürkheim (Stuttgart) DAIMLER AG DE-Germany Wörth DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, Unimog ES-Spain Samano DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz ES-Spain Vitoria DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz