Accomplice Liability for Unintentional Crimes: Remaining Within the Constraints of Intent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity Theft Literature Review

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Identity Theft Literature Review Author(s): Graeme R. Newman, Megan M. McNally Document No.: 210459 Date Received: July 2005 Award Number: 2005-TO-008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. IDENTITY THEFT LITERATURE REVIEW Prepared for presentation and discussion at the National Institute of Justice Focus Group Meeting to develop a research agenda to identify the most effective avenues of research that will impact on prevention, harm reduction and enforcement January 27-28, 2005 Graeme R. Newman School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany Megan M. McNally School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, Newark This project was supported by Contract #2005-TO-008 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Unfunded Mandates: a Unifying Principle of All Counties Ecounty Lines | November 2020

Protection from Unfunded Mandates: A Unifying Principle of All Counties eCounty Lines | November 2020 There are various protections in place for local governments from unfunded mandates, both in state statute, as well as the execution of laws by the Governor and his departments. However, there is no absolute protection. Collectively, commissioners—assisted by Colorado Counties Inc.—are the strongest defense against unfunded mandates. A statute enacted in 1991 prohibits unfunded mandates, with some exceptions. “No new state mandate or an increase in the level of service…shall be mandated by the general assembly or any state agency on any local government unless the state provides additional moneys to reimburse such local government for the costs …such mandate or increased level of service for an existing state mandate shall be optional on the part of the local government” (CRS 29-1-304.5). The Colorado Taxpayers Bill of Rights (TABOR) took this statute a step further by allowing local governments to end their participation in a program, if funding was inadequate. “Except for public education through grade 12 or as required of a local district by federal law, a local district may reduce or end its subsidy to any program delegated to it by the general assembly for administration” (Article X, Section 20(9)). Unfortunately, in 1995 these two provisions were defeated twice via State Supreme Court decisions. In the first case, Weld County attempted to withhold their portion of payments towards a public assistance program administered through the county. However, the court did not find this payment to be a subsidy (as referenced in TABOR) and declared that as an arm of the state, counties were essentially part of the state and therefore could not subsidize themselves, so the exemption was not allowed [Romer v. -

A Rationale of Criminal Negligence Roy Mitchell Moreland University of Kentucky

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 32 | Issue 2 Article 2 1944 A Rationale of Criminal Negligence Roy Mitchell Moreland University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Moreland, Roy Mitchell (1944) "A Rationale of Criminal Negligence," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 32 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol32/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RATIONALE OF CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE (Continued from November issue) RoY MOREL A D* 2. METHODS Op DESCRIBING THE NEGLIGENCE REQUIRED 'FOR CRIMINAL LIABILITY The proposed formula for criminal negligence describes the higher degree of negligence required for criminal liability as "conduct creating such an unreasonable risk to life, safety, property, or other interest for the unintentional invasion of which the law prescribes punishment, as to be recklessly disre- gardful of such interest." This formula, like all such machinery, is, of necessity, ab- stractly stated so as to apply to a multitude of cases. As in the case of all abstractions, it is difficult to understand without explanation and illumination. What devices can be used to make it intelligible to judges and juries in individual cases q a. -

Scmf-11-0000315 in the Supreme Court of the State

SCMF-11-0000315 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF HAWAI#I In the Matter of the Publication and Distribution of the Hawai#i Pattern Jury Instructions - Criminal ORDER APPROVING PUBLICATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF HAWAI#I PATTERN JURY INSTRUCTIONS - CRIMINAL (By: Recktenwald, C.J., Nakayama, McKenna, Pollack, and Wilson, JJ.) Upon consideration of the request of the Standing Committee on Pattern Criminal Jury Instructions to publish and distribute the revision of Criminal Instructions 6.01, 7.5, 10.00A(3), 10.05A, 10.05C, 10.07, 10.07A, 10.09, and 10.09A of the Hawai#i Pattern Jury Instructions - Criminal, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the request is granted as to the revisions proposed to Criminal Instructions 6.01, 7.5, and 10.00A(3), as amended in this order. IT IS FINALLY ORDERED that this approval for publication and distribution is not and shall not be considered by this court or any other court to be an approval or judgment as to the validity or correctness of the substance of any instruction. DATED: Honolulu, Hawai#i, May 5, 2017. /s/ Mark E. Recktenwald /s/ Paula A. Nakayama /s/ Sabrina S. McKenna /s/ Richard W. Pollack /s/ Michael D. Wilson 2 6.01 ACCOMPLICE A defendant charged with committing an offense may be guilty because he/she is an accomplice of another person in the commission of the offense. The prosecution must prove accomplice liability beyond a reasonable doubt. A person is an accomplice of another in the commission of an offense if: 1. With the intent to promote or facilitate the commission of the offense, he/she a. -

The Unnecessary Crime of Conspiracy

California Law Review VOL. 61 SEPTEMBER 1973 No. 5 The Unnecessary Crime of Conspiracy Phillip E. Johnson* The literature on the subject of criminal conspiracy reflects a sort of rough consensus. Conspiracy, it is generally said, is a necessary doctrine in some respects, but also one that is overbroad and invites abuse. Conspiracy has been thought to be necessary for one or both of two reasons. First, it is said that a separate offense of conspiracy is useful to supplement the generally restrictive law of attempts. Plot- ters who are arrested before they can carry out their dangerous schemes may be convicted of conspiracy even though they did not go far enough towards completion of their criminal plan to be guilty of attempt.' Second, conspiracy is said to be a vital legal weapon in the prosecu- tion of "organized crime," however defined.' As Mr. Justice Jackson put it, "the basic conspiracy principle has some place in modem crimi- nal law, because to unite, back of a criniinal purpose, the strength, op- Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley. A.B., Harvard Uni- versity, 1961; J.D., University of Chicago, 1965. 1. The most cogent statement of this point is in Note, 14 U. OF TORONTO FACULTY OF LAW REv. 56, 61-62 (1956): "Since we are fettered by an unrealistic law of criminal attempts, overbalanced in favour of external acts, awaiting the lit match or the cocked and aimed pistol, the law of criminal conspiracy has been em- ployed to fill the gap." See also MODEL PENAL CODE § 5.03, Comment at 96-97 (Tent. -

Parties to Crime and Vicarious Liability

CHAPTER 6: PARTIES TO CRIME AND VICARIOUS LIABILITY The text discusses parties to crime in terms of accessories and accomplices. Accessories are defined as accessory before the fact – those who help prepare for the crime – and accessories after the fact – those who assist offenders after the crime. Accomplices are defined as those who participate in the crime. Under the common law, accessories were typically not punished as much as accomplices or principle offenders; on the other hand, accomplices were usually punished the same as principal offenders. Accomplices and Accessories Before the Fact Under Ohio’s statutes, accomplices and accessories before the fact are now treated similarly, while accessories after the fact are treated separately under the obstruction of justice statute discussed later. Under Ohio’s complicity staute: (A) No person acting with the kind of culpability required for an offense…shall do any of the following: Solicit or procure another to commit the offense; Aid or abet another in committing the offense; Conspire with another to commit the offense… ; Cause an innocent or irresponsible person to commit the offense. (Ohio Revised Code, § 2923.03, 1986, available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/2923.03). Note that parts of the complicity statute – (A)(1) and (A)(3) – mention both solicitation and conspiracy. These two crimes are discussed in Chapter 7. The punishment for complicity is the same as for the principal offender; that is, if Offender A robs a liquor store and Offender B drives the getaway car, both offenders are subject to the same punishment, even though Offender A would be charged with robbery and Offender B would be charged with complicity (Ohio Revised Code, § 2923.03 (F), 1986, available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/2923.03). -

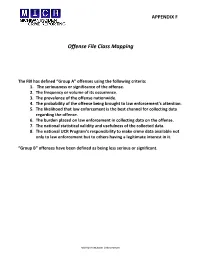

Offense File Class Mapping

APPENDIX F Offense File Class Mapping The FBI has defined “Group A” offenses using the following criteria: 1. The seriousness or significance of the offense. 2. The frequency or volume of its occurrence. 3. The prevalence of the offense nationwide. 4. The probability of the offense being brought to law enforcement’s attention. 5. The likelihood that law enforcement is the best channel for collecting data regarding the offense. 6. The burden placed on law enforcement in collecting data on the offense. 7. The national statistical validity and usefulness of the collected data. 8. The national UCR Program’s responsibility to make crime data available not only to law enforcement but to others having a legitimate interest in it. “Group B” offenses have been defined as being less serious or significant. MICHIGAN INCIDENT CRIME REPORT APPENDIX F Offense File Class Mapping Chart File MICR Offense Group NIBRS Class Description (A or B) Class Description 01000 Sovereignty Group B 90Z All Other 02000 Military Group B 90Z All Other 03000 Immigration Group B 90Z All Other 09001 Murder/Non‐Negligent Manslaughter Group A 09A Murder/Non‐Negligent Manslaughter 09002 Negligent Homicide/Manslaughter Group A 09B Negligent Manslaughter 09003 Negligent Homicide Vehicle/Boat/ Snowmobile/ORV Group B 90Z All Other 09004 Justifiable Homicide Group A 09C Justifiable Homicide 10001 Kidnapping/Abduction Group A 100 Kidnapping/Abduction 10002 Parental Kidnapping Group A 100 Kidnapping/Abduction 11001 Sexual Penetration Penis/Vagina CSC1 Group A 11A Forcible Rape 11002 -

Sanctions for Drunk Driving Accidents Resulting in Serious Injuries And/Or Death

Sanctions for Drunk Driving Accidents Resulting in Serious Injuries and/or Death State Statutory Citation Description of Penalty Alabama Ala. Code §§ 13A-6-20 & Serious Bodily Injury: Driving under the influence that result in the 13A-5-6(a)(2) serious bodily injury of another person is assault in the first degree, Ala. Code § 13A-6-4 which is a Class B felony. These felonies are punishable by no more than 20 years and no less than two years incarceration. Criminally Negligent Homicide: A person commits the crime of criminally negligent homicide by causing the death of another through criminally negligent conduct. If the death is caused while operating a motor vehicle while under the influence, the punishment is increased to a Class C felony, which is punishable by a prison term of no more than 10 years or less than 1 year and one day. Alaska Alaska Stat. §§ Homicide by Vehicle: Vehicular homicide can be second degree 11.41.110(a)(2), murder, manslaughter, or criminally negligent homicide, depending 11.41.120(a), & on the facts surrounding the death (see Puzewicz v. State, 856 P.2d 11.41.130(a) 1178, 1181 (Alaska App. 1993). Alaska Stat. Ann. § Second degree murder is an unclassified felony and shall be 12.55.125 (West) imprisoned for not less than 15 years nor more than 99 years Manslaughter is a class A felony and punishable by a sentence of not more than 20 years in prison. Criminally Negligent Homicide is a class B felony and punishable by a term of imprisonment of not more than 10 years. -

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Criminal

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Criminal Release 20, September 2019 NOTICE TO USERS: THE FOLLOWING SET OF UNANNOTATED MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS ARE BEING MADE AVAILABLE WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER, MATTHEW BENDER & COMPANY, INC. PLEASE NOTE THAT THE FULL ANNOTATED VERSION OF THESE MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS IS AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE FROM MATTHEW BENDER® BY WAY OF THE FOLLOWING LINK: https://store.lexisnexis.com/categories/area-of-practice/criminal-law-procedure- 161/virginia-model-jury-instructions-criminal-skuusSku6572 Matthew Bender is a registered trademark of Matthew Bender & Company, Inc. Instruction No. 2.050 Preliminary Instructions to Jury Members of the jury, the order of the trial of this case will be in four stages: 1. Opening statements 2. Presentation of the evidence 3. Instructions of law 4. Final argument After the conclusion of final argument, I will instruct you concerning your deliberations. You will then go to your room, select a foreperson, deliberate, and arrive at your verdict. Opening Statements First, the Commonwealth's attorney may make an opening statement outlining his or her case. Then the defendant's attorney also may make an opening statement. Neither side is required to do so. Presentation of the Evidence [Second, following the opening statements, the Commonwealth will introduce evidence, after which the defendant then has the right to introduce evidence (but is not required to do so). Rebuttal evidence may then be introduced if appropriate.] [Second, following the opening statements, the evidence will be presented.] Instructions of Law Third, at the conclusion of all evidence, I will instruct you on the law which is to be applied to this case. -

Criminal Law--Conspiracy and the Felony Murder Doctrine in Kentucky J

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 14 1940 Criminal Law--Conspiracy and the Felony Murder Doctrine in Kentucky J. Wirt Turner Jr. University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Turner, J. Wirt Jr. (1940) "Criminal Law--Conspiracy and the Felony Murder Doctrine in Kentucky," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 29 : Iss. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol29/iss1/14 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KENTUCKY LAw JOURNAL In conclusion, it is submitted that the felony murder doctrine in Kentucky is based on the same principles as the negligent murder doctrine, since to convict a defendant of murder for a death occuring during the commission of a felony there must first be a felony dangerous to life and, secondly, the death of the victim must be the necessary or natural consequence of the felony. J. GRiANVILLE CLARK CRIMINAL LAW-CONSPIRACY AND THE FELONY MURDER DOCTRINE IN KENTUCKY* Defendant was indicted jointly with two others for the crime of wilful murder by setting fire to a house and burning a child to death. The evidence showed that defendant was not near enough to aid and abet in the crime. -

What Does Intent Mean?

WHAT DOES INTENT MEAN? David Crump* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................. 1060 II. PROTOTYPICAL EXAMPLES OF INTENT DEFINITIONS......... 1062 A. Intent as “Purpose” ..................................................... 1062 B. Intent as Knowledge, Awareness, or the Like ............ 1063 C. Imprecise Definitions, Including Those Not Requiring Either Purpose or Knowledge .................. 1066 D. Specific Intent: What Does It Mean?.......................... 1068 III. THE AMBIGUITY OF THE INTENT DEFINITIONS.................. 1071 A. Proof of Intent and Its Implications for Defining Intent: Circumstantial Evidence and the Jury ........... 1071 B. The Situations in Which Intent Is Placed in Controversy, and the Range of Rebuttals that May Oppose It................................................................... 1074 IV. WHICH DEFINITIONS OF INTENT SHOULD BE USED FOR WHAT KINDS OF MISCONDUCT?....................................... 1078 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................... 1081 * A.B. Harvard College; J.D. University of Texas School of Law. John B. Neibel Professor of Law, University of Houston Law Center. 1059 1060 HOFSTRA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1059 I. INTRODUCTION Imagine a case featuring a manufacturing shop boss who sent his employees into a toxic work environment. As happens at many job sites, hazardous chemicals unavoidably were nearby, and safety always was a matter of reducing their concentration. This attempted solution, however, may mean that dangerous levels of chemicals remain. But this time, the level of toxicity was far higher than usual. There is strong evidence that the shop boss knew about the danger, at least well enough to have realized that it probably had reached a deadly level, but the shop boss disputes this evidence. The employees all became ill, and one of them has died. The survivors sue in an attempt to recover damages for wrongful death. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 ..............................................................................................