Dalrev Vol51 Iss4 Pp553 558.Pdf (3.200Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Joe) Papers Coll 00505 1 Gift of Joe Rosenblatt, 2006 Extent

MS ROSENBLATT (Joe) Papers Coll 00505 Gift of Joe Rosenblatt, 2006 Extent: 14 Boxes (2 metres) Dates: 1990-2005 (bulk 2001-05) This collection consists of manuscript drafts and other material related to various writing projects by poet and visual artist Joe Rosenblatt, including Parrot Fever (published by Exile Editions, 2002) as well two as-yet unpublished works: Dog Poems, a collaboration with Vancouver-based poet Catherine Owen and photographer Karen Moe, and Hogg Variations/The Lunatic Muse, a collaboration with Barry Callaghan. The collection also contains a large volume of correspondence, primarily e-mail. Box 1 Parrot Fever 35 Folders Consists of manuscript drafts, correspondence and reproductions of Michel Christensen’s collages for Rosenblatt’s Parrot Fever, published by Exile Editions, 2002. Folders 1-27 Manuscript drafts Folder 1 “Earliest,” 2000 WP Folders 2 Early drafts, 2001 WP Folders 3-4 Early drafts, “Third Draft,” 2001 WP and WP with holograph revisions Folder 5 Early drafts, 2001 WP with holograph revision Folders 6-7 Early drafts, 2001 WP with holograph revisions Folder 8 Fourth draft, 2001 WP Folder 9 Draft (sent via e-mail to French translator Andree Christensen), 2002 1 MS ROSENBLATT (Joe) Papers Coll 00505 Folder 10 Draft, 2002 WP Folder 11 Draft, 2002 WP with holograph revisions (+ 2 e-mails) Folders 12-15 Drafts, 2002 WP Folder 16 Draft, 2002 WP with holograph revisions (+ 1 e-mail) Folder 17 Draft, 2002 WP (+ editorial correspondence) Folder 18 Draft, 2002 WP Folders 19-20 Drafts, 2002 WP with holograph revisions -

APRIL 2015 - NISSAN-IYAR 5775 Volume 7, Issue 8, April 2015 EDWARD DAVIS, Rabbi YOSEF WEINSTOCK, Associate Rabbi STEPHEN KURTZ, President

“ YOUNG ISRAEL OF HOLLYWOOD-FT. LAUDERDALE APRIL 2015 - NISSAN-IYAR 5775 Volume 7, Issue 8, April 2015 EDWARD DAVIS, Rabbi YOSEF WEINSTOCK, Associate Rabbi STEPHEN KURTZ, President (picture of Synagogue) , President President , BARATZ MICHAEL Rabbi ociate Ass WEINSTOCK, YOSEF Rabbi DAVIS, EDWARD 2 1 20 June , 10 Issue , 4 Volume 2 1 20 JUNE - 2 7 57 TAMMUZ - IVAN S Requested Service Change 5566 - (up-side down address and bulk mail inditia) 962 (954) Fax: 7877 - 966 (954) Phone: Permit No. 1329 No. Permit www.yih.org FACILITY FL. SO. 33312 FL Lauderdale, Ft. PAID POSTAGE U.S. Road Stirling 3291 Organization FT. LAUDERDALE FT. - HOLLYWOOD of ISRAEL YOUNG Nonprofit “ Page 2 Young Israel Hollywood-Ft. Lauderdale April 2015 SIMCHAS FROM OUR FAMILIES -MAZEL TOV TO: BIRTHS Suchie & Raisy Gittler on the birth of their granddaughter Sophia Rose to Daniel & Dorith Gittler Lenny & Ellen Hoenig on the birth of their grandson Mordechai to Yossi & Zisa Farkas Seth & Rebecca Kinzbrunner on the birth of their daughter Eliana Sara. Mazel Tov to grandparents Norman & Meryl Palgon and great-uncle & aunt Neil & Karen Lyman Michael & Nili Davis on the birth of their son Yehuda & Morit Soffer on the birth of their son Tzvi & Rachael Schachter on the birth of their grandson to Eli & Rachelle Schachter. Mazel Tov to great-grandparents Sam & Malca Schachter ENGAGEMENTS & MARRIAGES Larry &Tobi Reiss on the engagement of their daughter Nina to Mordechai Braun David & Linda Feigenbaum on the marriage of their daughter Kayla to Ariel Levy Jay & Chani Dennis on the marriage of their daughter Talia to Jake Freiman. -

Purdy-Al-2071A.Pdf

AL PURDY PAPERS PRELIMINARY INVENTORY Table of Contents Biographical Sketch .................................. page 1 Provenance •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 0 ••••••••• page 1 Restrictions ..................................... 0 ••• page 1 General Description of Papers ••••••••••••••••••••••• page 2 Detailed Listing of Papers ............................ page 3 Appendix •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• page 52 • AL f'lJRDY PAPEllS PRELnlI~ARY INVENroRY BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Al Purdy was born in 1918 in Hoo ler, Ontario . His formal education eeied after only two years of high scnool. He spent the next years of his life wandering from job to job, spending the war years with the R.C.A.F. He spent some time on the West Coast and in 1956 be returned east.. He has received Canada Council Grants wbich enabled him to t ravel into the interior of British Columbia (1960) and to Baffin Island (1965) and a tour of Greece (1967). He has published 10 books of poetry and edited three books, and has contributed to various magazines. His published books are; The En ch~"ted Echo (1944) Pr. ssed 00 Sand (1955) Emu Remember (1957) Tne Grafte So Longe to Lerne (1959) r Poems for all the AnnetteG (1962) The Blur in Between (1963 earihoo Horses (1965) Covernor Ceneral'5 weda1 North of Summer (1967) ·Wild Grape Wine (1968) The New Romans (1968) Fifteeo Wind. (1969) l've Tasted My Blood. Selected poems of Mil ton Acorn (1969) He has also reviel-.'ed many new books and h&s written some scripts for the C.B.C. PROVENANCE These paperG were purchased from Al Purdy witb fun~from The Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fu.."'\d in 1969. RESTRICTIONS None. -

Frank Davey: Publications

Frank Davey: Publications Books: Poetry: D-Day and After. Vancouver: Tishbooks, 1962. 32 pp. City of the Gulls and Sea. Victoria, 1964. 34 pp. Bridge Force. Toronto: Contact Press, 1965. 77 pp. The Scarred Hull. Calgary: Imago, 1966. 40 pp. Four Myths for Sam Perry. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1970. 28 pp. Weeds. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1970. 30 pp. Griffon. Toronto: Massassauga Editions, 1972. 16 pp. King of Swords. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1972. 38 pp. L’an trentiesme: Selected Poems 1961-70. Vancouver: Vancouver Community Press, 1972. 82 pp. Arcana. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1973. 77 pp. The Clallam. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1973. 42 pp. War Poems. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1979. 45 pp. The Arches: Selected Poems, edited and introduced by bpNichol. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1981. 105 pp. Capitalistic Affection!. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1982. 84 pp. Edward & Patricia. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1984. 40 pp. The Louis Riel Organ & Piano Company. Winnipeg: Turnstone Press, 1985. 77 pp. The Abbotsford Guide to India. Victoria, B.C.: Press Porcépic, 1986. 104 pp. Postcard Translations. Toronto: Underwhich Editions, 1988. 32 pp. Postenska Kartichka Tolkuvanja, tr. Julija Veljanoska. Skopje: Ogledalo, 1989. 32 pp. Popular Narratives. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1991. 88 pp. The Abbotsford Guide to India, Gujarati translation by Nita Ramaiya. Bombay: Press of S.N.D.T. Women's University, 1995. 96 pp. Cultural Mischief: A Practical Guide to Multiculturalism. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1996. 70 pp. Dog. Calgary: House Press, 2002. 12 pp. Risky Propositions. Ottawa: above/ground press, 2005. 30 pp. Back to the War. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005. 126 pp. Johnny Hazard! Armstrong, BC: by the skin of me teeth press, 2009. -

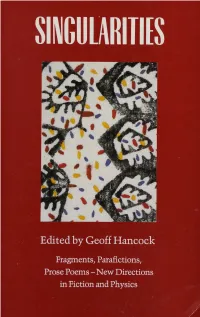

C19 Singularities.Pdf

Singularities 1111111111\\ I \\\\II\ 1\1111\ 1\\1 1111111111 11111111111111111111111 3 9345 00923319 2 CLC SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS PR 9073 846 1990 Singularities . Edited by Geoff Hancoclz Singularities: Fragments, Parafictions, Prose Poems - New Directions in Fiction and Physics Black Moss Press <e> Geoff Hancock 1990 Published by Black Moss Press, 1939 Al ace, Windsor, Ontario, Canada NSW lMS. Black Moss Press books are distributed by Firefly Books, 250 Sparks Avenue, Willowdale, Ontario M2H 2S4 Flnancial assistance toward publication was gratefully received from the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council. Cover design: Turkish folk artist Printed and bound in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under ti tie: Singularities ISBN 0-88753-203-9 1. Canadian prose literature !English) - 20th century. I. Hancock, Geoff, 1946- PS8329.S46 1990 C818'.540808 C90-090052-0 PR9194.9.S46 1990 I have the universe all to myself. The universe has me all to itself. - Peter Matthiessen, The Snow Leopard Contents ckno' led ement · w urry Th Atomic tructur of Silence 11 av Godfrey from I Ching Kanada 12 v ndolyn MacEwen An Evening with Grey Owl 16 Erin Moure The Origin of Horses 19 J Ro enblatt from Bride of the Stream 19 Michael Dean An Aural History of Lawns 21 ean o huigin from The Nightmare Alphabet 27 nne zumigalski The Question 29 Karl Jirgen Strappado 30 Lola LeMire Tostevin A Weekend at the Semiotics of Eroticism Colloquium Held at Victoria College 33 maro Kambourelli It Was Not A Dark and Stormy Night 34 George McWhirter Nobody's Notebook 36 Michael Bullock Johannes Weltseele Enters the Garden 45 Claire Harris After the Chinese 50 Patrick Lane Ned Coker's Dream 54 Gay Allison The Slow Gathering Of 60 Eugene McNamara Falling in Place 64 hp Nichol The Toes 69 Rod Willmot from The Ribs of Dragonfl_y 71 Paul Dutton Uncle Rebus Clean Song 73 Fred W ab Elite 78 Daphne Marlatt&. -

Dalrev Vol58 Iss1 Pp149 169.Pdf (6.954Mb)

Douglas Barbour Review Article Poetry Chronicle V: It's interesting how we've been told over and over again that somehow in the seventies all the promises of the sixties have been broken. We are asked to believe that the glories of art and religiosity and politics have all faded. Thus the marvelous sense of exploration and opening new doors in poetry must be a thing of the past and whatever is being written today, however well done, cannot possibly match the poetry of the sixties in terms of breaking new ground. But, surely, I reply, the new ground is always there to be broken and art comes from individual artists not decades? At any rate, the spiritual depression many peo ple seem to speak from in the seventies is not mine, and to my eye (even if most of the young writers lack the sense of language a whole generation in the sixties had) some extraordinarily exciting writing is taking place (admittedly, much of it from writers who began in the sixties-my point is that they have not died with the decade). Out of around forty books this time through, about five truly put me off, most are good, if not finally overwhelming, and a few are among the best books I've come across this decade. A search through previous 'chronicles' would reveal at least one, sometimes two or three, super books per year: that's a lot of really good poetry, no matter how you look at it. The world may indeed be falling apart but Canadian poetry is not. -

The Collection Offiles for Exile, Which Is Published in Toronto, Contains

MS. CALLAGHAN (BARRY) COLLECTION COLL. 268 SCOPE AND CONTENT: EXILE: A LITERARY QUARTERLY The collection offiles for Exile, which is published in Toronto, contains manuscripts with notes, revisions, instructions to the printer, and galley proofs for poems, short stories, essays, plays and art which appeared in Exile from 1972 to 1995. Exile was founded in 1972 by Barry Callaghan, a Toronto writer and teacher. The first three issues were published by Atkinson College, York University, Toronto. Since volume 1, number 4 (1974) Callaghan has published it. He is and has been the sole editor. Exile aims to publish the best Canadian and international writing by known and unknown writers. It has published short stories by Margaret Atwood, Marie-Claire Blais, Morley Callaghan, Timothy Findley, Mavis Gallant, Robert Markle, Joyce Carol Oates; poems by Yehuda Amichai, Margaret Avison, Leonard Cohen, Michael Lally, John Montague; plays by the Armchambault Theatre Collective; drawings by David Annesley, Marcel Marceau, Robert Zend; photographs by David Goldblatt. The matenal was given in two sections and there is, therefore, some overlap. Boxes 1-22 were donated in 1988 and contain material up to volume 13. Boxes 23-56 were donated in 1995 and contain material fi'om volume 11 to volume 19. Each volume has about 160 pages except for the double issues which have 260 pages. Volume 16 is a special large-format retrospective. EXTENT: 56boxes9.5 metres Edna Hajnal June 1989 Richard Moll June 1996 (-><. I. ). MS CALLAGHAN (BARRY) COLLECTION 2 COLL. 268 CHRONOLOGY:CALLAGHAN,BARRY 1937 Born in Toronto 1960 Received B.A. j]-om St. -

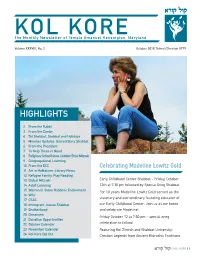

To Open the October 2018 Issue

KOLThe Monthly Newsletter of KORETemple Emanuel Kensington, Maryland Volume XXXVIII, No. 2 October 2018 Tishrei/Chesvan 5779 HIGHLIGHTS 2 From the Rabbi 3 From the Cantor 4 Tot Shabbat, Shabbat and Holidays 5 Member Updates, Sacred Story Shabbat 6 From the President 7 To Help Those in Need 8 Religious School News, October B’nai Mitzvah 9 Congregational Learning 10 From the ECC Celebrating Madeline Lowitz Gold 11 Art in HaMakom, Library News 12 Refugee Family, Play Reading 13 Global Mitzvah Early Childhood Center Shabbat – Friday, October 14 Adult Learning 12th at 7:30 pm followed by Special Oneg Shabbat 15 Warren G. Stone Rabbinic Endowment For 10 years Madeline Lowitz Gold served as the 16 WRJ visionary and extraordinary founding educator of 17 CSAC 18 Immigrant Justice Shabbat our Early Childhood Center. Join us as we honor 19 Brotherhood and celebrate Madeline! 20 Donations Friday October 12 at 7:30 pm – special oneg 21 Donation Opportunities 22 October Calendar celebration to follow! 23 November Calendar Featuring Kol Zimrah and Shabbat University: 24 Kol Kore Opt Out Creation Legends from Ancient Midrashic Traditions / KOL KORE | 1 from the Rabbi Special Shabbat on Justice and Immigrants, October 26th Guest Speaker: Heidi Altman, National Immigration Justice Center We live in a time of growing xenophobia and racism. As the world’s refugee population grows, so do efforts to demonize the refugee. Our own country has a history that is at best complicated and at worst, as we are currently witnessing, capable of demagoguery and cruelty. Jewish moral teachings are clear. Our very story in antiquity is that of refugees, wanderers from a land of oppression in search of a promised land. -

MS Coll 00740

Ms. Sherman, Ken papers Coll. 00740 Gift of Kenneth Sherman 2016 Includes drafts and notes for: Black Flamingo, Cost of Living, Jogging With the Great Ray Charles, Clusters, My Father Kept His Cats Well Fed and Words for Elephant Man. Poem drafts, early essays, course work from York University and literary correspondence, 1980s – 2000s (Irving Layton, Seymour Mayne, Eric Ormsby, Cynthia Ozick, Robyn Sarah, Joe Rosenblatt, Czeslaw Milosz, Philip Roth and others) also form part of this accession. Extent: 21 boxes (4 metres) Biographical note from Canadian Poetry Online: Kenneth Sherman was born in Toronto in 1950. He has a BA from York University, where he studied with Eli Mandel and Irving Layton, and an MA in English Literature from the University of Toronto. While a student at York, Sherman co-founded and edited the literary journal WAVES. From 1974-1975 he traveled extensively through Asia. He began his teaching career in 1975 at York's Atkinson College. He is a full-time faculty member at Sheridan College where he teaches Humanities and Communications; he also teaches a course in creative writing at York University. In 1982, Sherman was writer-in-residence at Trent University. In 1986 he was invited by the Chinese government to lecture on contemporary Canadian literature at universities and government institutions in Beijing. In 1988, he received a Canada Council grant to travel through Poland and Russia. This experience inspired several of the essays in his book Void and Voice (1998). Sherman lives in Toronto with his wife, Marie, an artist, and their two children. Box 1 Black Flamingo 26 folders Draft manuscripts ‘The Book of Salt’ Drafts and notes Folders 1-2 Black Flamingo Word processed drafts Folders 3-7 ‘The Book of Salt’ Holograph drafts Folders 8-10 Black Flamingo Holograph drafts Folders 11-12 Black Flamingo Holograph and word processed drafts Folders 13-14 Black Flamingo Holograph drafts 1 Ms. -

EARLE BIRNEY: a Tribute

jihffcr<& EARLE BIRNEY: A Tribute EARLE BIRNEY: A Tribute EDITED BY Sioux Browning and Melanie J. Little COMPILED BY Chad Norman PRODUCTION AND DESIGN BY Sioux Browning COVER AND INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS BY Heather Spears PRINTED BY OK Graphics Produced in cooperation with PRISM international. Contents Copyright © 1998 PRISM international for the authors. Net proceeds from the sale of this book will go towards the annual PRISM international Earle Birney Prize for Poetry. PRISM international, a magazine of contemporary writing, is pub lished four times per year by the Creative Writing Program at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z1. ISSN 0032.8790 TABLE OF CONTENTS bill bissett life is like a gypsy violin regardless 5 Al Purdy Birney: Dean of Canadian Poets 7 D. G. Jones For Earle Birney 15 Phil Thomas Authors Anonymous 16 Peter Trower Toronto the Moist 18 Janis Rapoport A Personal Memory 19 Louis Dudek from Notebook 1964-1978 22 I.B.Iskov When He Died, He Took One Last Poem With Him 24 Jacob Zilber A Little Shelter 25 Robert Sward The Generous and Humane Voice 27 Jan de Bruyn For My Former Friend and Colleague 30 Hilda Thomas To A Wild Beard 31 Earle Birney A Wild Beard Replies 33 Peter Trower Journeyman 34 Alison Acker Remembering Earle 35 Doug Lochhead An Acquaintance Remembers 38 Chad Norman The Blackened Spine 41 Glen Sorestad Suitcases of Poetry 44 Georgejohnston A Few Personal Notes 45 Fred Candelaria Amazing Labyrinth 47 Wayson Choy Nothing Would Be The Same Again 48 Linda Rogers The Perfect Consonant Rhyme 50 Wail an Low Once High On A Hill 52 Pirn wi**"* ik M m A A * i RISM international POETRY PRiZE EARLE BIRNEY PRIZE FOR POETRY RISM international will enter its fortieth year in 1999. -

Ms. Drache, Sharon Abron Coll. Papers 00684 (2B Annex) Gift of Sharon Abron Drache, 2014

Ms. Drache, Sharon Abron Coll. papers 00684 (2B Annex) Gift of Sharon Abron Drache, 2014 Includes extensive correspondence, manuscripts, etc. with Joe Rosenblatt, David Gurr; drafts, research and correspondence related to Barbara Klein-Muskrat: Then and Now; The Lubavitchers Are Coming to Second Avenue; Ritual Slaughter; The Mikveh Man; The Golden Ghetto; The Magic Pot; correspondence, research and drafts for piece on Richard Landon and the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library; Arthur Drache material; unpublished children’s stories; family material; ghost writing; mentoring and other material related to the life and work of Sharon Abron Drache. Extent: 40 boxes (6 metres) Biographical family note from the Ontario Jewish Archives Sharon Abron Drache fonds: Sharon Abron Drache attended Forest Hill Collegiate(graduating in 1962) and then completed an undergraduate degree and post-graduate diploma in Psychology at the University of Toronto, the latter from the Institute of Child Study. She was enrolled as a special student in the Department of Religion at Carleton University from 1974-78. She has published four books of adult fiction, The Mikveh Man, Ritual Slaughter, The Golden Ghetto, Barbara Klein-Muskrat – then and now, and two children’s books, The Magic Pot and The Lubavitchers are coming to Second Avenue. She has also worked as a literary journalist and book reviewer for several newspapers and journals including, The Globe and Mail, Ottawa Citizen, Books In Canada, the Glebe Report and The Ottawa and Western Jewish Bulletins. Murray Abramowitz was born in 1912 in Toronto. His parents were David (1884-1963) and Sarah (nee Winfield) (1885-1955). -

MS Coll 00286

MS BROWN (Russell) Papers Coll 00286 Extent: 64 boxes Dates: 1972-95 Russell Brown’s literary papers include his editorial and correspondence files from his tenure as editor of Lakehead University Review (1972-75); Descant (1978-83); joint editor, An Anthology of Canadian Literature in English (1982-83); and as poetry editor at McClelland and stewart (1983-88). Additional Brown material can be found in MS Coll. 00361. 2 MS. BROWN (RUSSELL) PAPERS COLL. HfJ" SCOPE & CONTENT 2.86 Russell Brown's papers include his editorial and correspondence files from his tenure as editor of Lakehead University Review (1972-75); Descant (1978-83); joint editor, An Anthology of Canadian Literature in English (1982-83); and as poetry editor at McClelland and stewart (1983-88). He succeeded Dennis Lee in this position so that some authors' files may contain correspondence from the latter. Brown edited about thirty books of poetry, including works by Roo Borson, Lorna Crozier, Mary di Michele, Ralph Gustafson, Irving Layton, Douglas LePan, Susan Musgrave and Al Purdy. Some manuscripts are included with the correspondence. Manuscripts for which the authors sought Brown's editorial and critical suggestions may contain lengthy comments which, in many cases, resulted in the works being revised and later pUblished. 3 MS. BROWN (RUSSELL) PAPERS COLL. 28'6 CONTAINER LISTING Boxes Editorial files, Lakehead University Review and 1-4 Descant Box 1 Lakehead University Review, 1972-75, mainly correspondence. 4 folders. Descant, 1979-83. Correspondence, with manuscripts, 1979-84 (except for Dennis Lee issue, 1982) 1980 Hugh Hood, 1 TLSi Eli Mandel, 1 ALSi David Watmough, 1 TLS 1981 P.K.