From Outlaw to Consultant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paradise Lost , Book III, Line 18

_Paradise Lost_, book III, line 18 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% ++++++++++Hacker's Encyclopedia++++++++ ===========by Logik Bomb (FOA)======== <http://www.xmission.com/~ryder/hack.html> ---------------(1997- Revised Second Edition)-------- ##################V2.5################## %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% "[W]atch where you go once you have entered here, and to whom you turn! Do not be misled by that wide and easy passage!" And my Guide [said] to him: "That is not your concern; it is his fate to enter every door. This has been willed where what is willed must be, and is not yours to question. Say no more." -Dante Alighieri _The Inferno_, 1321 Translated by John Ciardi Acknowledgments ---------------------------- Dedicated to all those who disseminate information, forbidden or otherwise. Also, I should note that a few of these entries are taken from "A Complete List of Hacker Slang and Other Things," Version 1C, by Casual, Bloodwing and Crusader; this doc started out as an unofficial update. However, I've updated, altered, expanded, re-written and otherwise torn apart the original document, so I'd be surprised if you could find any vestiges of the original file left. I think the list is very informative; it came out in 1990, though, which makes it somewhat outdated. I also got a lot of information from the works listed in my bibliography, (it's at the end, after all the quotes) as well as many miscellaneous back issues of such e-zines as _Cheap Truth _, _40Hex_, the _LOD/H Technical Journals_ and _Phrack Magazine_; and print magazines such as _Internet Underground_, _Macworld_, _Mondo 2000_, _Newsweek_, _2600: The Hacker Quarterly_, _U.S. News & World Report_, _Time_, and _Wired_; in addition to various people I've consulted. -

Steve Wozniak

Steve Wozniak. http://www.woz.org http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Wozniak http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_box http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_computer Steve Wozniak’s patent: Microcomputer for use with video display. Apple 1 manual. Apple 1 manual (PDF). http://apple2history.org/ http://www.digibarn.com/ http://www.macmothership.com/ http://www.multimedialab.be http://www.mast-r.org Wozniak’s early inspirations came from his father Jerry who was a Loc- kheed engineer, and from a fictional wonder-boy: Tom Swift. His father infected him with fascination for electronics and would often check over young Woz’s creations. Tom Swift, on the other hand, was for Woz an epitome of creative freedom, scientific knowledge, and the ability to find solutions to problems. Tom Swift would also attractively illustrate the big awards that await the inventor. To this day, Wozniak returns to Tom Swift books and reads them to his own kids as a form of inspiration. John Draper explained to Wozniak the Blue Box, a device with which one could (mis)use the telephone system by emulating pulses (i.e. phone phreaking). Although Draper instructed Woz not to produce and especially not sell the gadgets on account of the possibility of being discovered, Wo- zniak built and sold Blue Boxes for $150 a piece. Wozniak met Steve Jobs while working a summer job at HP, and they began selling blue boxes to- gether. Many of the purchasers of their blue boxes were in fact discovered and sure enough John Draper was linked to their use. 1975. By 1975, Woz dropped out of the University of California, Berkeley (he would later finish his degree in 1987) and came up with a computer that eventually became successful nationwide. -

Joseph Migga Kizza Fourth Edition

Computer Communications and Networks Joseph Migga Kizza Guide to Computer Network Security Fourth Edition Computer Communications and Networks Series editor A.J. Sammes Centre for Forensic Computing Cranfield University, Shrivenham Campus Swindon, UK The Computer Communications and Networks series is a range of textbooks, monographs and handbooks. It sets out to provide students, researchers, and nonspecialists alike with a sure grounding in current knowledge, together with comprehensible access to the latest developments in computer communications and networking. Emphasis is placed on clear and explanatory styles that support a tutorial approach, so that even the most complex of topics is presented in a lucid and intelligible manner. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/4198 Joseph Migga Kizza Guide to Computer Network Security Fourth Edition Joseph Migga Kizza University of Tennessee Chattanooga, TN, USA ISSN 1617-7975 ISSN 2197-8433 (electronic) Computer Communications and Networks ISBN 978-3-319-55605-5 ISBN 978-3-319-55606-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-55606-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939601 # Springer-Verlag London 2009, 2013, 2015 # Springer International Publishing AG 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Jims Virtual World

December 21, 2010, VOLUME 1, ISSUE 20 JIMS VIRTUAL WORLD A NEWSLETTER BY THE DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY VoIP: The Modern day Phone Phreaking Phone Phreaking was a rage during the 1950s - John Draper better known as Captain Crunch used to hack into tele- phone lines to make long distance calls. In today’s world, we use VoIP supported applications but during the early days of phone hacking, there was the Blue Box. The most famous ex phone phreaks were Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak during their college days. In an old interview, Steve Wozniak stated that once they both had nearly been arrested for using it but they got away when they explained to the police officer that, “It is a music calibration tool.” Phone Phreaking was the first form of hacking; automated machines replaced manual phone exchanges and these automated machines used certain pitches of sound to connect the calls. By the use of the Blue Box, these audio signals were bypassed just as VoIP today uses digital signals to bypass the audio signals. The Blue Box was a legal and monetary complication for the telecom industry with AT&T taking stern action against all the Phone Phreakers. Captain Crunch and many other pioneers and users of this technology were arrested and prosecuted for stealing from the telephone company. Not too different from today’s scenario, the Indian Government’s stand on VoIP is still being debated upon, the intelligence bureau thinks VoIP is too undisciplined for any regulation or surveillance, and hence a threat to national security. -

History of Hacking Part 1: Phone Phreaking Bruce Nikkel

History of Hacking Part 1: Phone Phreaking Bruce Nikkel Published in HISTEC Journal, a publication by the Swiss computer museum Enter (https://enter.ch). This is part one of a four part series on the history of computer hacking. The words "hacker" and "hacking" in the context of technology was first used in the Tech Model Railway club at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the 1950s. A “hack” by students referred to a clever technical or engineering achievement (sometimes in the form of pranks) for the purpose of fun and learning. Early hackers and hacking were not associated with criminal activity. To begin this series we start with hacking activity on the earliest public global network, the original telephone system. In this article we explore early hackers known as "phone phreaks" or “phreakers” and the technical methods they used. Before home computers or the Internet became popular, a hacking technique called "phone phreaking" was used to exploit weaknesses in the global telephone system. The word "phreak" is an English misspelling of "freak" using the "ph" from the word phone (the switching of "f" with "ph" for hacking is also used today with the word phishing). Phone phreaks learned how telephone networks functioned and manipulated central switching infrastructure by generating tones and pulses. Unlike the hacks from MIT students, phone phreaking was considered criminal activity in many countries where wire fraud laws prevented unauthorized misuse of network systems and bypassing telephone billing to make free calls. When phone companies started to transition from human switchboard operators to automated dialing and switching systems they needed a way to pass signals from the customer's phone to the telephone switching infrastructure. -

The Journal of AUUG Inc. Volume 24 ¯ Number 3 September 2003

The Journal of AUUG Inc. Volume 24 ¯ Number 3 September 2003 Features: Going 3D with Blender: A toy train 7 The Linux System Administrator’s Security Guide 12 2003 and Beyond (part 2) 18 AUUGN Book Review: Google Hacks 29 Linux and Open Source in Government: CfP 30 AUUGN Book Review: Essential CVS 31 UNIX and Bioinformatics 32 Tuning and Optimizing Red Hat Advanced Server for Oracle9i Database 35 AUUGN Book Review: Drive-by Wi-Fi 49 Play Encoded DVDs in Xine 5O Interview: Australian Sun HPC Team 52 AUUGN 2003: The Photos 58 News: Public Notices 5 AUUG: Corporate Members 31 AUUG: Chapter Meetings and Contact Details 63 Regulars: President’s Column 3 My Home Network 5 ISSN 1035-7521 Print post approved by Australia Post - PP2391500002 AUUG Membership and General Correspondence The AUUG Secretary Editorial AUUG Inc PO Box 7071 Con Zymaris auugn(~.auu.q.or.q.au Baulkham Hills BC NSW 2153 Telephone: 02 8824 9511 A few words on the power of words. I am a great or 1800 625 655 (Toll-Free) advocate of the need for technical people, AUUG Facsimile: 02 8824 9522 people, to get out and speak their mind, to make their Email: [email protected] opinions, ideas and ideals heard by the great AUUG Management Committee mainstream; by those whose utilisation patterns of Email: a u u,[email protected] u technology we have foreseen and whose lives we are helping to shape the digital future of. President Greg Lehey PO Box 460 Words have the power to anger, the power to inspire. -

Founding a Hackerspace

Founding a Hackerspace An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to: Project Advisor: Francis Hoy Faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment for the requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Submitted by Joseph Schlesinger Md Monirul Islam Kelly MacNeill Date: Professor Frank Hoy Project Advisor Abstract This report is the written component of our project that explores the hackerspace phenomenon. The report discusses the background and history of hackerspaces along with the social context of the modern hackerspace. Interviews of various hackerspaces were conducted and analyzed in order to gain insight into their operation and management. The research conducted was used to establish a hackerspace as a for-profit business. We describe the process of launching this entity, MakeIt Labs LLC in Lowell, MA. Also included is the business plan created for MakeIt Labs. Acknowledgements We would like to show our gratitude to the many individuals and organizations that helped us with our project by supplying us with data about the hackerspace community. These individuals allowed us know first-hand what it was like to be part of the maker community. Specifically, we would like to thank the founders and members of the following hackerspaces for giving their valuable time and valuable information: Hacker Dojo, NYC Resistor, Sprout & Co, BUILDS, and Noisebridge. Our appreciation goes to all the people who have put information about hackerspaces online. Finally, we would like to thank our project advisor, Frank Hoy, for his assistance and guidance throughout the project experience. Authorship page This project report was produced by Md Monirul Islam, Kelly MacNeill and Joseph Schlesinger. -

Steve Jobs: the Man Who Thought Different by Karen Blumenthal, 2012, Feiwel & Friends

Discussion Guide Steve Jobs: the Man Who Thought Different by Karen Blumenthal, 2012, Feiwel & Friends BOOK SYNOPSIS “From the start, his path was never predictable. Steve Jobs was given up for adoption at birth, he dropped out of college after one semester, and at the age of twenty-one, he created Apple in his parents’ garage with his friend Steve Wozniak. Quickly rising to the top of his industry, Jobs pushed all boundaries and cultivated what became the intrinsic hallmark of his genius – his perfectionism, taste, and design style. But soon after success, Jobs was fired from the top spot of his own company. Finding himself a beginner again, Jobs entered into one of the most creative periods of his life. Through Pixar, the iPod, and the iPhone, Jobs revolutionized the major industries of movies, music, and phones. An avid seeker of disciplines of the mind and body, he battled cancer for nearly a decade, became the ultimate CEO, and made the world want every product he touched. Critically acclaimed author Karen Blumenthal takes us to the core of this complicated and legendary man while simultaneously exploring the evolution of computers. Illustrated throughout with black- and-white photos, this is the story of a man who changed the world.” ABOUT KAREN BLUMENTHAL “Ole Golly told me if I was going to be a writer I better write down everything … so I’m a spy that writes down everything.” —Harriet the Spy, Louise Fitzhugh Like Harriet M. Welsch, the title character in Harriet the Spy, award-winning author Karen Blumenthal is an observer of the world around her. -

1972 Can Be Made with the Use of a Blue Box and a Plastic Toy Whistle That Comes in Cap’N Crunch Cereal Boxes

History 329/SI 311/RCSSCI 360 Computers and the Internet: A global history The Dark Side: Hackers, Spam, and Black Markets Today } Revisions to the syllabus and end of the course } Hackers } Spam } Vandalism on Wikipedia } Black markets on “darknets” } Next time Proposed changes to syllabus } April 7: session on China } Guest lecturer Silvia Lindtner } Last class April 12 — NO CLASS April 14 } No final exam — 1250-1500 word essay instead } Why does history matter? How has learning the history of computers changed your view of the present? } Adjustment to percentages for final grade } Midterms 1 and 2 – each 30 pct of grade (was 20) } Final essay — 10 pct of grade Hackers Tweet this John Draper, A.K.A. “Captain Crunch,” discovers that free phone calls 1972 can be made with the use of a blue box and a plastic toy whistle that comes in Cap’n Crunch cereal boxes. The whistle duplicates a 2600-hertz tone to unlock AT&T’s phone network. 1979 The first computer “worm” is created at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center. The program is meant to make computers more efcient, but later hackers modify worms into computer viruses that destroy or alter data. source (all blue slides): Dell Computer Captain Crunch (John Draper) } “Phreaking” } Built “blue boxes” } Connected with Homebrew computer club } 2600 magazine (1984-) PC hackers (1975-present) } Structure: distributed computing } Individual PCs in homes, offices } PC hacker culture } Far larger, highly fragmented group } Time of day no longer important } Mainframe and mini hackers: usually nighttime, to -

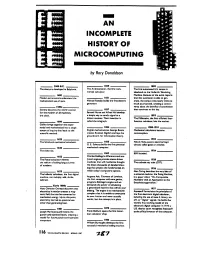

An Incomplete History of Microcomputing

l - - - - - w ' w ' ww - - - - AN - a- 5 =- - - INCOMPLETE ^ v ^ - - i HISTORY OF - - vv a cars MICROCOMPUTING ^ r v wssw v s F - by Rory Donaldson 3000 B.C. 1820 1890 The abacus is developed in Babylonia. The Arithmometer, the first com- The first automated U.S. census is mercial calculator. tabulated on the Hollerith Tabulating 1400 Machine. Because of the extra reports Moslem astronomers understand the 1831 that this automaton is able to gen- mathematical use of zero. Michael Faraday builds the first electric erate, the census costs nearly twice as generator. much as projected, creating a contro- I SOOs versy about the benefits of automation Geneva becomes the world's center 1837 that continues to this day. for the mother of all machines, Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail develop the clock. a simple way to send a signal to a 1893 distant receiver. Their invention is The Millionaire, the first efficient four- 1600 called the telegraph. function calculator, hits the market. Galileo brings together the exper- iential and mathematical into a single 1854 1900-1910 stream of inquiry that leads to the English mathematician George Boole Mechanical calculators become scientific method. creates Boolean Algebra and lays the commonplace. groundwork for information theory. 1623 1903 The Schickard mechanical calculator. 1855 _ Nikola Tesa patents electrical logic G. E. Scheutz builds the first practical circuits called gao or switches. 1630 mechanical computer. The slide rule. 1924 1862 _ IBM founded. 1652 Charles Babbage's difference and ana- The Pascal calculator relieves lytical engines promise steam-driven 1921 the tedium of adding long columns machines that will mechanize thought. -

Hacking for Dummies‰ 4TH EDITION

www.it-ebooks.info www.it-ebooks.info Hacking FOR DUMmIES‰ 4TH EDITION by Kevin Beaver, CISSP www.it-ebooks.info Hacking For Dummies®, 4th Edition Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 111 River Street Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2013 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permit- ted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http:// www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its af!li- ates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

Hacktivism: an Analysis of the Motive to Disseminate

HACKTIVISM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE MOTIVE TO DISSEMINATE CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of SCIENCE by Warren V. Held, B.A. San Marcos, TX December 2012 HACKTIVISM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE MOTIVE TO DISSEMINATE CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION Committee Members Approved: ______________________________ Jay D. Jamieson, Chair ______________________________ J. Pete Blair ______________________________ Jeffrey M. Cancino Approved: ____________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT by Warren V. Held 2012 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Warren V. Held, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the family members, friends, professors, and others who have lent support, assistance, and guidance throughout the course of my education. This manuscript was submitted on October 26th, 2012. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...............................................................................................