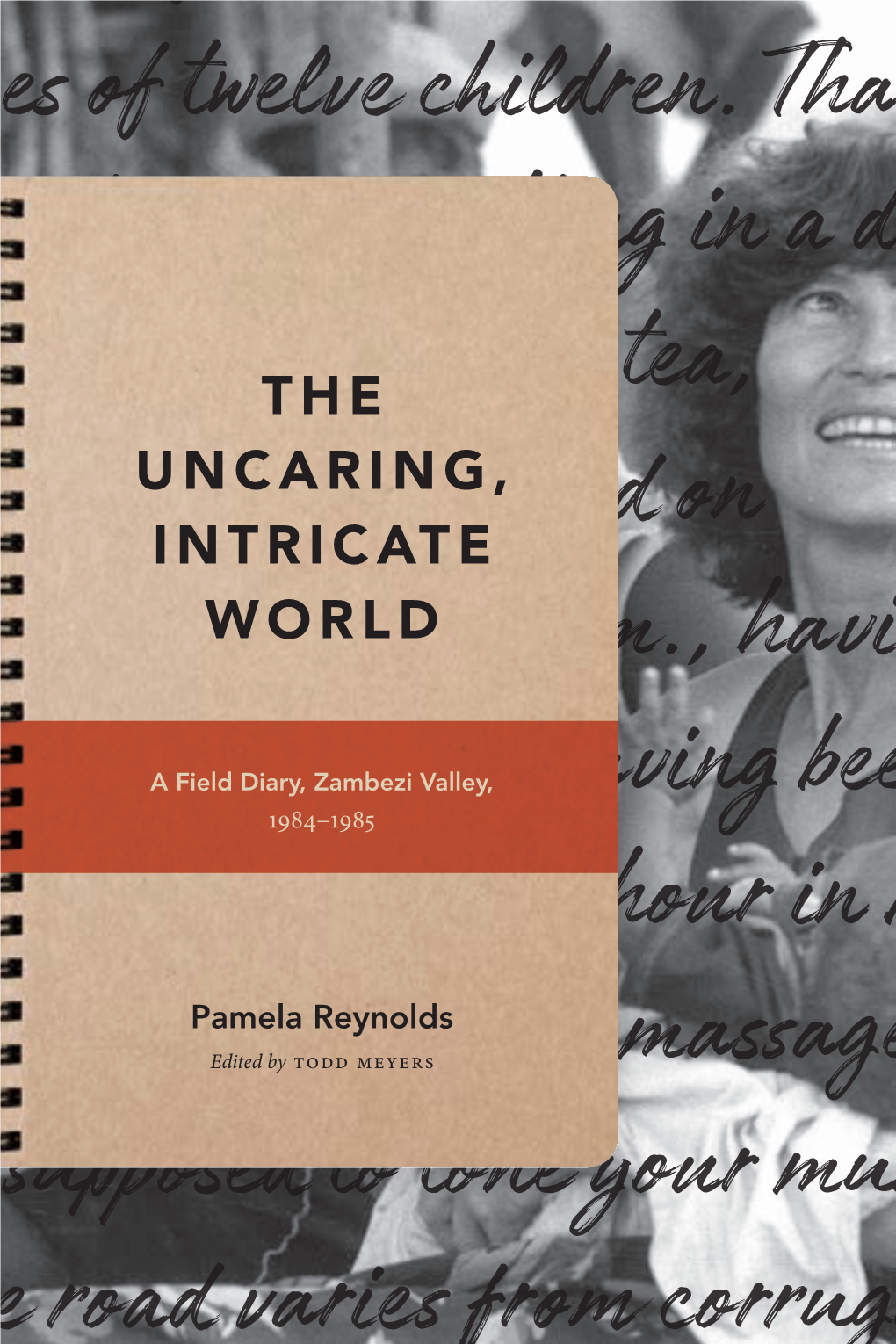

Exposed to the Eyes of Twelve Children. That Which I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Primary and Secondary Production in Lake Kariba in a Changing Climate

AN ANALYSIS OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY PRODUCTION IN LAKE KARIBA IN A CHANGING CLIMATE MZIME R. NDEBELE-MURISA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Philosophiae in the Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof. Charles Musil Co-Supervisor: Prof. Lincoln Raitt May 2011 An analysis of primary and secondary production in Lake Kariba in a changing climate Mzime Regina Ndebele-Murisa KEYWORDS Climate warming Limnology Primary production Phytoplankton Zooplankton Kapenta production Lake Kariba i Abstract Title: An analysis of primary and secondary production in Lake Kariba in a changing climate M.R. Ndebele-Murisa PhD, Biodiversity and Conservation Biology Department, University of the Western Cape Analysis of temperature, rainfall and evaporation records over a 44-year period spanning the years 1964 to 2008 indicates changes in the climate around Lake Kariba. Mean annual temperatures have increased by approximately 1.5oC, and pan evaporation rates by about 25%, with rainfall having declined by an average of 27.1 mm since 1964 at an average rate of 6.3 mm per decade. At the same time, lake water temperatures, evaporation rates, and water loss from the lake have increased, which have adversely affected lake water levels, nutrient and thermal dynamics. The most prominent influence of the changing climate on Lake Kariba has been a reduction in the lake water levels, averaging 9.5 m over the past two decades. These are associated with increased warming, reduced rainfall and diminished water and therefore nutrient inflow into the lake. The warmer climate has increased temperatures in the upper layers of lake water, the epilimnion, by an overall average of 1.9°C between 1965 and 2009. -

Second Technical Consultation on the Development and Management of the Fisheries of Lake Kariba

FAO Fisheries Report No. 766 SAFR/R766 (En) ISSN 0429-9337 Report of the SECOND TECHNICAL CONSULTATION ON THE DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE FISHERIES OF LAKE KARIBA Kariba, Zimbabwe, 30 November–1 December 2004 Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: Sales and Marketing Group Information Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00100 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (+39) 06 57053360 FAO Fisheries Report No. 766 SAFR/R766 (En) Report of the SECOND TECHNICAL CONSULTATION ON THE DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE FISHERIES OF LAKE KARIBA Kariba, Zimbabwe, 30 November–1 December 2004 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2005 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries ISBN 92-5-105367-7 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] © FAO 2005 iii PREPARATION OF THIS DOCUMENT This is the report adopted on 1 December 2004 in Kariba, Zimbabwe, by the second Technical Consultation on the Development and Management of the Fisheries of Lake Kariba. -

IN Lake KARIBA ~As Development Ad Ndon)

• View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquatic Commons THE A leA JOU L OF (Afr. J Trop. Hydrobiol. Fish) Yo. 1 1994 ASPECTS OF THE BIOLOGY OF THE lAKE TANGANYIKA SARDINE, LIMNOTHRISSA n illustrated key to the flinji. (Mimeographed MIODON (BOULENGER), IN lAKE KARIBA ~as Development Ad ndon). R. HUDDART ision des Synodontis Kariba Research Unit, Private Bag 24 CX, CHOMA, Zambia. e Royal de I'Afrique 'en, Belgium. 500p. Present address:- ~). The ecology of the 4, Ingleside Grove, LONDON, S.B.3., U.K. is (Pisces; Siluoidea) Nigeria. (Unpublished ABSTRACT o the University of Juveniles of U11lnothrissa 11liodon (Boulenger) were introduced into the man-made Lake Kariba in ngland). 1967-1968. Thirty months of night-fishing for this species from Sinazongwe, near the centre of the Kariba North bank. from 1971 to 1974 are described. Biological studies were carried out on samples of the catch during most of these months. Limnological studies were carried out over a period of four months in 1973. Li11lnothrissa is breeding successfully and its number have greatly increased. [t has reached an equilibrium level of population size at a [ower density than that of Lake Tanganyika sardines, but nevertheless is an important factor in the ecology of Lake Kariba. The growth rate, size at maturity and maximum size are all less than those of Lake Tanganyika Li11lnothrissa. A marked disruption in the orderly progression of length frequency modes occurs in September, for which the present body of evidence cannot supply an explanation. INTRODUCTION light-attracted sardines in Lake Kariba were The absence of a specialised, plankti tested in 1970 and early 1971. -

Thezambiazimbabwesadc Fisheriesprojectonlakekariba: Reportfroma Studytnp

279 TheZambiaZimbabweSADC FisheriesProjectonLakeKariba: Reportfroma studytnp •TrygveHesthagen OddTerjeSandlund Tor.FredrikNæsje TheZambia-ZimbabweSADC FisheriesProjectonLakeKariba: Reportfrom a studytrip Trygve Hesthagen Odd Terje Sandlund Tor FredrikNæsje NORSKINSTITI= FORNATURFORSKNNG O Norwegian institute for nature research (NINA) 2010 http://www.nina.no Please contact NINA, NO-7485 TRONDHEIM, NORWAY for reproduction of tables, figures and other illustrations in this report. nina oppdragsmelding279 Hesthagen,T., Sandlund, O.T. & Næsje, T.F. 1994. NINAs publikasjoner The Zambia-Zimbabwe SADC fisheries project on Lake Kariba: Report from a study trip. NINA NINA utgirfem ulikefaste publikasjoner: Oppdragsmelding279:1 17. NINA Forskningsrapport Her publiseresresultater av NINAs eget forskning- sarbeid, i den hensiktå spre forskningsresultaterfra institusjonen til et større publikum. Forsknings- rapporter utgis som et alternativ til internasjonal Trondheimapril 1994 publisering, der tidsaspekt, materialets art, målgruppem.m. gjør dette nødvendig. ISSN 0802-4103 ISBN 82-426-0471-1 NINA Utredning Serien omfatter problemoversikter,kartlegging av kunnskapsnivået innen et emne, litteraturstudier, sammenstillingav andres materiale og annet som ikke primært er et resultat av NINAs egen Rettighetshaver0: forskningsaktivitet. NINA Norskinstituttfornaturforskning NINA Oppdragsmelding Publikasjonenkansiteresfritt med kildeangivelse Dette er det minimum av rapporteringsomNINA gir til oppdragsgiver etter fullført forsknings- eller utredningsprosjekt.Opplageter -

Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute Project Report Number 67

Annual report 1990 Item Type monograph Authors Machena, C. Publisher Department of National Parks and Wild Life Management Download date 29/09/2021 15:18:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/25005 Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute Project Report Number 67 1990 Annual Report Compiled by C. Machena ,ional Parks and Wildlife Management. COMMITTEE OF MANAGEMENT MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM Mr K.R. Mupfumira - Chief Executive Officer DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT Dr. W.K. Nduku - Director and Chairman of Committee of Management Mr. G. Panqeti - Deputy Director Mr.R.B. Martin - Assistant Director (Research) Mr. Nyamayaro - Assistant Director (Administration) LAKE KARIBA FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE Dr. C. Machena - Officer - in - Charge Mr. N. Mukome - ExecutiveOfficer and Secretary of Committee of Management. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Officer-in-Charge's Reoort 4 The Zambia/Zimbabwe SADCC Lake Kariba Fisheries Research And DeveloQment Pro:iect 12 Comparative Study Of Growth OfLimnothrissanijodon (Boulenger) in Lake Kariba 18 An Analysis Of The Effects Of Fishing Location And Gear On Kapenta Catches On Lake Kariba 19 Hydro-acoustic Surveys In Lake Kariba 20 The Pre-recruitment Ecology of The Freshwater SardineLimnothrissamíodon(Boulenger) In Lake Kariba 22 Report On Short Course In Zooplankton Quantitative Sampling Methods held at the Freshwater Biology Laboratory Windermere From 19 to 30 November 1990... 25 Report On Training: Post-Graduate Training - Humberside Polytechnic, U.K 32 Postharvest Fish Technology In Lake Kariba. Zimbabwe 33 Assessment Of The Abundance Of Inshore Fish Stocks And Evaluating The Effects Of Fishing Pressure On The Biology Of Commercially Important Species And Ecological Studies OnSynodontiszambezensís.......35 11. -

LAKE KARIBA: a Man-Made Tropical Ecosystem in Central Africa MONOGRAPHIAE BIOLOGICAE

LAKE KARIBA: A Man-Made Tropical Ecosystem in Central Africa MONOGRAPHIAE BIOLOGICAE Editor J.ILLIES Schlitz VOLUME 24 DR. W. JUNK b.v. PUBLISHERS THE HAGUE 1974 LAKE KARIBA: A Man-Made Tropical Ecosystem in Central Africa Edited by E. K. BALON & A. G. CaCHE DR. W. JUNK b.v. PUBLISHERS THE HAGUE 1974 ISBN- 13: 978-94-010-2336-8 e-ISBN-13: 978-94-010-2334-4 001: 10.1007/978-94-010-2334-4 © 1974 by Dr. W. Junk b.v., Publishers, The Hague Softcover reprint of the hardcover I st edition Cover design M. Velthuijs, The Hague Zuid-Nederlandsche Drukkerij N.V., 's-Hertogenbosch GENERAL CONTENTS Preface . VII Abstract IX Part I Limnological Study of a Tropical Reservoir by A. G. CacHE Contents of Part I. 3 Introduction and Acknowledgements . 7 Section I The Zambezi catchment above the Kariba Dam: general physical background 11 1. Physiography 13 2. Geology and soils . 18 3. Climate .. 25 4. Flora, fauna and human population. 41 Section II The rivers and their characteristics. 49 5. The Zambezi River . 51 6. Secondary rivers in the lake catchment 65 Section III Lake Kariba physico-chemical characteristics 75 7. Hydrology .. 77 8. Morphometry and morphology . 84 9. Sampling methodology 102 10. Optical properties . 108 11. Thermal properties 131 12. Dissolved gases 164 13. Mineral content 183 Section IV Conclusions . 231 14. General trophic status of Lake Kariba with particular reference to fish production. 233 Literature cited. 236 Annex I 244 Annex II .. 246 V Part II Fish Production of a Tropical Ecosystem by E. -

An Integrated Study of Reservoir-Induced Seismicity and Landsat Imagery at Lake Kariba, Africa

GREGORYB. PAVLIN CHARLESA. LANGSTON Department of Geosciences The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802 An Integrated Study of Reservoir-Induced Seismicity and Landsat Imagery at Lake Kariba, Africa A combined study of reservoir-induced earthquakes and Landsat Imagery yields information on geology and tectonics that either alone would not provide. I INTRODUCTION threat to life and property; (2) they offer a unique class of earthquakes which may be pre- ARTHQUAKES,depending upon their depth vented, controlled, and possibly predicted; (3) Eof origin and geographic location, are the re- they provide a class of earthquakes that can be sult of different types of physical mechanisms. easily monitored; and (4) the understanding of Perhaps the most interesting occurrences of the physics of these earthquakes would offer earthquakes are those linked, both directly and clues regarding the nature of other classes of indirectly, to the actions of men. Examples shallow earthquakes. ABSTRACT:The depth and seismic source parameters of the three largest reservoir-induced earthquakes associated with the impoundment of Lake Kariba, Africa, were determined using a formalism of the generalized inverse technique. The events, which exceeded magnitudes, mb, of 5.5, consisted of the foreshock and main event (0640 and 0901 GMT, 23 September 1963) and the principal aftershock (0703 GMT, 25 September 1963). Landsat imagery of the reservoir region was exploited as an independent source of infornation to de- termine the active fault location in conjunction with the teleseismic source parameters. The epicentral proximity and the comparable source parameters of the three events suggests a common normal fault with an approximate strike of S 9"W, a dip of 62", and rake of 266". -

Seismic Observation and Seismicity of Zimbabwe Mr

Seismic Observation and Seismicity of Zimbabwe Mr. Innocent Gibbon Tirivanhu MASUKWEDZA (2016 Global Seismology course) Meteorological Services Department of Zimbabwe 1. Introduction The Seismology section falls under the Meteorological Services Department of Zimbabwe. Currently, the department is functional under the Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate as a result of its main purpose being to contribute towards the safety of both life and property of Zimbabwe inhabitants. 2. Historical Background of Seismicity Measurements The need to monitor the seismicity of Zimbabwe came about by the construction of the Kariba dam as a way to monitor reservoir induced seismicity, but the idea was further expanded to include natural earthquakes. By then, the seismological station network composed of four analogue stations namely Bulawayo, Karoi, Mt Darwin and Chiredzi and these operated up to early 1990s. Although the dam construction began early in the 1950’s, seismograph stations were not deployed to monitor seismic activity until 1959, the year the dam was impounded. Since then, seismic activity in and around Zimbabwe has continuously been monitored. For the period 1959 to date, over 4,000 earthquakes in and around the country have been recorded. The largest earthquake recorded is that of magnitude 6.1 which occurred at Lake Kariba on September 23, 1963. The instruments to measure the seismicity of the country were issued to St George’s School (located in the city of Bulawayo) and later transferred to the Lawley Road site (situated in the same city) in 1903 with the arrival of Father Goetz. The main historical events after the arrival of Father Goetz are: 1950 – Dam wall construction of Lake Kariba and the sudden need for a seismological station. -

Mapping Resource Conflicts on Lake Kariba

CHAPTER 6 Competing Claims in a Multipurpose Lake: Mapping Resource Conflicts on Lake Kariba Wilson Mhlanga1 & Kefasi Nyikahadzoi2 Abstract Lake Kariba is a transboundary artificial water body originally constructed for the generation of hydro-electric power. It is now a multi-purpose resource that supports economic activities such as commercial fishing, artisanal fishing, aquaculture, tourism and water transport. These economic activities have given rise to intra-sectoral and inter-sectoral resource-use conflicts. This paper discusses these conflicts. The paper also recommends possible interventions which can be employed to enhance stakeholder dialogue and conflict resolution. 1. Introduction Lake Kariba is an artificial impoundment in Southern Africa on the Zambezi River (Figure 6.1). The lake is a transboundary resource that is shared between Zambia and Zimbabwe. Kariba dam (Photo 6.1) was built during the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland between 1955 and 1959, to provide hydro-electric power to Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). According to Coche (1971), the Federal Hydro-Electric Board was constituted to oversee the construction of the Kariba dam. In 1956, the Federal Power Board was created to replace the Federal Hydro-Electric Board. The mandate of the new Board was the generation and distribution of electricity within the Federation. In 1964, the Federal Power Board was replaced by the Central African Power Corporation (CAPCOR). CARPCOR was later replaced by the Zambezi River Authority (ZRA). The lake has a total surface area of 5 500 km2 at capacity, a maximum width of 40km, a mean width of 19.4km, a maximum depth of 120 metres, a mean depth of 29.2 metres and a shoreline length of 2 164km (Kenmuir 1983). -

SEISMIC OBSERVATION NETWORK in ZIMBABWE Patricia Mavazhe and Marimira Kwangwari

MANAGING WAVEFORM DATA AND METADATA FOR SEISMIC NETWORKS; 14-18 January 2013, Kuwait City, Kuwait SEISMIC OBSERVATION NETWORK IN ZIMBABWE Patricia Mavazhe and Marimira Kwangwari METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT 1 Zimbabwe is bounded on the north and northwest by Zambia , southwest by Botswana , Mozambique on the east, South Africa on the south. ZIMBABWE IN BRIEF • Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in Southern Africa, covering an area of 390,757 square kilometres (150,872 square miles). • Zimbabwe lies between latudes 15° and 23°S, and longitudes 25° and 34°E • The country has a tropical climate with a rainy season usually from late October to March. The climate is moderated by the alWtude. 3 INTRODUCTION • Zimbabwe has been monitoring earthquakes since 1959 when the first seismic staon was installed in Bulawayo. • In 1963 Zimbabwe operated a six component World Wide Seismograph Staon Network (WWSSN). By then the system was analogue. • Recording was by ink and pen on photographic paper and then conWnuous running paper. Data from these staons was then sent to Goetz (BUL) for analysis and archiving. • Zimbabwe signed a facility agreement that resulted in the building of an auxiliary staon AS120-MATP 4 SEISMICITY OF ZIMBABWE 5 The MAP above shows that the country can be divided into three seismic zones namely. a. Mid-Zambezi basin (area I)-Most active seismic zone, this is mainly due to reservoir induced seismicity from the Lake Kariba and the EARS. • Seismic activity around Lake Kariba is attributed to induced seismicity and it correlates with the infilling of the dam in 1963 and pure tectonics. -

4: Lake Kariba to Great Zimbabwe Ruins Day 5

Day 1 – 2: Lusaka to Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe TANZANIA With an optional stay on the Lake Kariba houseboats MALAWI We travel to Lake Kariba on day one for the option to relax for ANGOLA Lake Malawi ZAMBIA Lilongwe two nights while cruising the wilds of Lake Kariba, a perfect place Lusaka to get to know your fellow travellers. Relax on the deck of the Lake Kariba Blantyre Victoria Falls Matusadona Chobe Harare boat and in the jacuzzi as we visit Matusadona National Park, a Etosha sanctuary for elephant, buffalo, waterbuck, lion and the NAMIBIA Hwange ZIMBABWE Africat Ghanzi Matopos Great Zimbabwe endangered black rhino. Skeleton Okavango Bulawayo Coast Windhoek Delta Swakopmund MOZAMBIQUE Namib BOTSWANA Matusadona National Park fronts onto the Lake with much of its Sossusvlei Desert Johannesburg game having been rescued and released here when the Lake Fish River ESWATINI Canyon was filled. The park also has good numbers of hippo and Orange River REPUBLIC OF Durban O SOUTH AFRICA TH crocodile and the birdlife around the lake is luxuriant including SO LE fish eagles, bee-eaters, many different storks and herons, Lamberts Bay Stellenbosch Addo plovers, darters and waders. Sunrise over the Lake, as dawn’s Cape Town Gansbaai Port Elizabeth light breaks through the stark outlines of the driftwood trees and CAPE reflects in the waters of the man-made dam, with only the calls AGULHUS of the birds breaking the peaceful silence, is a scene of serene beauty. Key THE ROUTE GAME PARK The houseboat has bedrooms, a jacuzzi and the houseboat crew ADD ON Garden Route to Jo’burg cook our meals. -

Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe

Fish poplLlation changes in the Sanyati Basin, Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe D.H.S. Kenmuir Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute, Department of National Parks and Wildlife Management, Zimbabwe Large-fish population changes in the Sanyati Basin of Lake Kariba This paper considers the major natural large-fish population between 1960 and 1975 are evaluated and discussed. The early changes in the Sanyati Basin of Lake Kariba (Figure 1) between lake population following closure of the dam wall in 1958 was similar to the pre-impoundment riverine population with Labeo 1960 and 1975. With the exception of Jackson (1960) who dealt spp., Distichodus spp., Clarias gariepinus and two characid with the immediate effect of darn closure on the river fish species dominating gill-net catches. Exceptions were mormyrids, population, nothing empirical has yet been published on this scarce in the new lake although abundant in the river, and Oreochromis mortimeri, scarce in the river but expanding rapidly aspect of the biology of Lake Kariba fish, despite the lake be in the lake. Productivity in the new lake in terms of ichthyomass ing in existence now for 25 years_ The subject has, however, relative to later years was high. In later years following closure been discussed partially and in general terms by van der Lingen several of the early abundant mostly potamodromous species declined rapidly (C. gariepinus, Labeo spp., Distichodus spp.,) and (1973), Bowmaker, Jackson & Jubb (1978) and Kenmuir (1978, by 1975 they were unimportant. Mormyrids, cichlids and two 1983), while unpublished data on some aspects are those of silurid species increased significantly in catches as did the Donnelly (1971), and the report ofKenmuir (1977), from which characin, Hydrocynus vittatus; the latter as a result of the expan sion of the freshwater sardine population, from 1970.