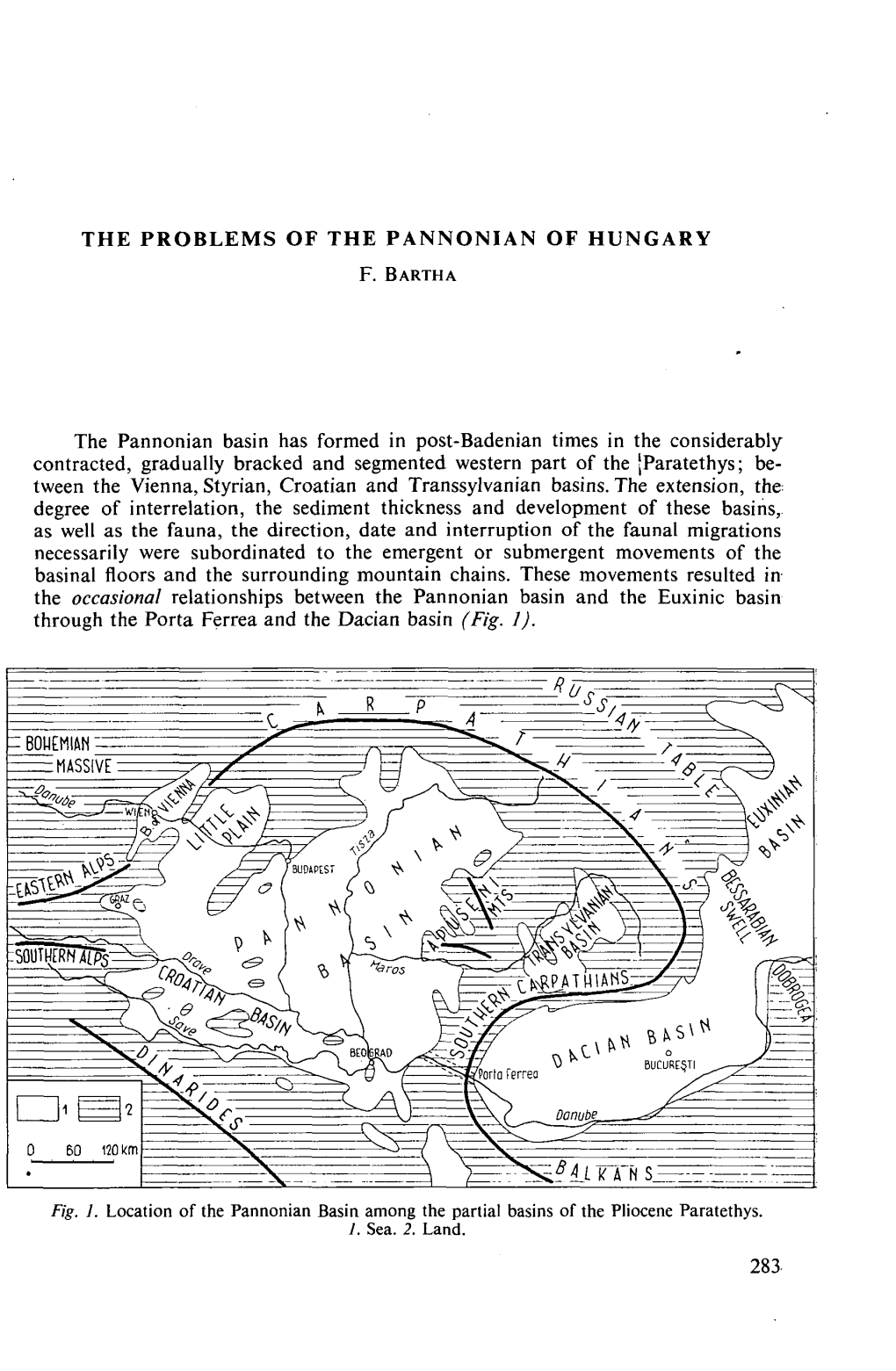

The Pannonian Basin Has Formed in Post-Badenian Times in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

Methodism in Hungary 1898-1920

Methodist History, 47:3 (April 2009) Methodism in Hungary ZOLTÁN KOVÁCS 1898-1920: The Antecedents of Methodist Mission in Hungary and the “Macedonian Call” The first representatives of Methodism in Hungary were Matthew Simpson, a bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and William Fairfield Warren, a minister of the New England Conference in 1857 after attending the World Convention of the Evangelical Alliance in Berlin, Germany. Enroute to Constantinople and Palestine following the convention, they interrupted their journey to spend a weekend in the Hungarian capital, Pest-Buda, at invitation of some anti-Habsburg opposition leaders they had met in Germany.1 Five years later Warren, then Professor at the Methodist Episcopal Missionary Institute in Berlin and Ludwig Sigismund Jacoby, founder and superintendent of the Germany Missionary conference, stopped again in Pest-Buda for three days. They were hosted by Adrian van Andel, a former Methodist lay minister in Hamburg who pastored the German-speaking Reformed Affiliated Church in the Hungarian capital.2 Despite these early positive encounters, a perma- nent Methodist work was not established in Hungary until the 1890s. Two circumstances appear to have influenced the beginning of missionary activities at that time. Probably the most important local factor was a group of Swabian men in the Bácska region of southern Hungary. A schoolteacher sub- scribed to Der Christliche Apologete, a periodical published in Cincinnati/Ohio, through which the Christian based temperance circles of Újverbász (Vrbas in Serbia today) and Bácsszenttamás (Srbobran) had learned of Methodism and decided to contact a Methodist minister. The first two attempts to establish a relationship failed, but the young pastor of Vienna, Robert Möller was willing to respond to the invitation. -

VIII. 31.) Korm

130. szám MAGYAR KÖZLÖNY MAGYARORSZÁG HIVATALOS LAPJA 2016. augusztus 31., szerda Tartalomjegyzék 257/2016. (VIII. 31.) Korm. rendelet Az önkormányzati ASP rendszerről 67743 258/2016. (VIII. 31.) Korm. rendelet Az egészségügyi szolgáltatások Egészségbiztosítási Alapból történő finanszírozásának részletes szabályairól szóló 43/1999. (III. 3.) Korm. rendelet módosításáról 67798 259/2016. (VIII. 31.) Korm. rendelet A honvédelemért felelős miniszter irányítása alatt álló központi hivatalok és költségvetési szervi formában működő háttérintézmények megszűnésével összefüggő egyes kormányrendeletek módosításáról és az Európai Rendőr-akadémia (CEPOL) székhelyének kialakítását célzó beruházással összefüggő közigazgatási hatósági ügyek nemzetgazdasági szempontból kiemelt jelentőségű üggyé nyilvánításáról és az eljáró hatóságok kijelöléséről szóló 466/2013. (XII. 5.) Korm. rendelet hatályon kívül helyezéséről 67798 260/2016. (VIII. 31.) Korm. rendelet Új tűzoltólaktanyák létrehozását és fejlesztését célzó beruházások megvalósításával összefüggő közigazgatási hatósági ügyek nemzetgazdasági szempontból kiemelt jelentőségű üggyé nyilvánításáról 67822 15/2016. (VIII. 31.) HM rendelet A honvédek jogállásáról szóló 2012. évi CCV. törvény egyes rendelkezéseinek végrehajtásáról szóló 9/2013. (VIII. 12.) HM rendelet és a honvédelmi miniszter és a Honvéd Vezérkar főnöke által alapítható és adományozható elismerésekről szóló 15/2013. (VIII. 22.) HM rendelet módosításáról 67824 16/2016. (VIII. 31.) HM rendelet Az egyes honvédelmi miniszteri rendeleteknek a honvédelmi miniszter irányítása alá tartozó központi hivatalok szervezeti integrációjával összefüggő módosításáról 67827 35/2016. (VIII. 31.) NFM rendelet A nemzeti fejlesztési miniszter ágazatába tartozó szakképesítések szakmai és vizsgakövetelményeiről 67832 36/2016. (VIII. 31.) NFM rendelet A földgázpiaci egyetemes szolgáltatáshoz kapcsolódó árak képzéséről szóló 29/2009. (VI. 25.) KHEM rendelet és a földgáz rendszerhasználat árszabályozásának kereteiről szóló 74/2009. (XII. 7.) KHEM rendelet módosításáról 68228 1465/2016. (VIII. -

2011. Évi Népszámlálás 3

Központi Statisztikai Hivatal 2011. ÉVI NÉPSZÁMLÁLÁS 3. Területi adatok 3.3. Baranya megye Pécs, 2013 © Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, 2013 ISBN 978-963-235-347-0ö ISBN 978-963-235-999-9 Készült a Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Pécsi főosztályán, az Informatikai főosztály, a Népszámlálási főosztály és a Tájékoztatási főosztály közreműködésével Felelős kiadó: Dr. Vukovich Gabriella elnök Főosztályvezető: Dr. Horváth József Összeállította: Berettyánné Halas Judit Dr. Berkéné Molnár Andrea Fritz János Horváthné Takács Ibolya Konstanzerné Nübl Erzsébet Laták Marianna Molnár Györgyné Németh Tibor Nyakacska Mária Slézia Rita A táblázó programot készítette: Papp Márton A kéziratot lektorálta: Dr. Novák Zoltán Tördelőszerkesztők: Bulik László Kerner-Kecskés Beatrix Trybek Krisztina Weisz Tamás További információ: Berettyánné Halas Judit Telefon: (+36-72) 533-319, e-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.nepszamlalas.hu [email protected] (+36-1) 345-6789 (telefon), (+36-1) 345-6788 (fax) Borítóterv: Lounge Design Kft. Nyomdai kivitelezés: Xerox Magyarország Kft. – 2013.054 TARTALOM Köszöntöm az Olvasót! ................................................................................................5 Összefoglaló ...................................................................................................................7 1. A népesség száma és jellemzői ..................................................................................9 1.1. A népesség száma, népsűrűség ..........................................................................9 -

The People Behind the Numbers

Public Disclosure Authorized The People Behind Public Disclosure Authorized the Numbers: Developing a Framework for the Effective Implementation of Local Equal Opportunity Plans Public Disclosure Authorized Handbook for the Implementation of Local Equal Opportunity Programs in Hungary Public Disclosure Authorized Disclaimer This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / the World Bank. The findings, interpretation, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Hungarian Government. Copyright Statement The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) Ministry of Human Capacities (Arany János u. 6-8, 1051, Budapest, Hungary); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Vasile Lascăr Street, No 31, Et 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania) This report was prepared under the Advisory Services Agreement for Policy Advice to Support the Implementation of the National Social Inclusion Strategy of Hungary signed between the World Bank and the Ministry of Human Capacities on March 17, 2015. Acknowledgments The team would like to express its gratitude to peer reviewers Joost de Laat, Katalin Szatmári, Maria Beatriz Orlando and Andor Ürmös for their technical inputs and comments during the review process, as well as to Christian Bodewig, Alina Nona Petric and Manuel Salazar for their helpful comments. -

Magyarország Közigazgatási Helynévkönyve, 2014. Január 1

Magyarország közigazgatási helynévkönyve 2014. január 1. Gazetteer of Hungary 1st January, 2014 Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Hungarian Central Statistical Office Budapest, 2014 © Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, 2014 © Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2014 ISSN 1217-2952 Felelős szerkesztő – Responsible editor: Waffenschmidt Jánosné főosztályvezető – head of department További információ – Contact person: Nagy Ferenc Andrásné szerkesztő – editor (tel: 345-6366, e-mail: [email protected]) Internet: http://www.ksh.hu [email protected] 345-6789 (telefon), 345-6788 (fax) Borítóterv – Cover design: Nyomdai kivitelezés – Printed by: Xerox Magyarország Kft. – Táskaszám: 2014.076 TARTALOM ÚTMUTATÓ A KÖTET HASZNÁLATÁHOZ ............................................................................................................... 5 KÓDJEGYZÉK ..................................................................................................................................................................... 11 I. ÖSSZEFOGLALÓ ADATOK 1. A helységek száma a helység jogállása szerint ............................................................................................................................................................ 21 2. A főváros és a megyék területe, lakónépessége és a lakások száma ........................................................................................................................... 22 3. A települési önkormányzatok főbb adatai .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development PROGRAMME

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development PROGRAMME-COMPLEMENT (PC) to the AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME (ARDOP) (2004-2006) Budapest June 2009 ARDOP PC modified by the ARDOP MC on 7 March 2006 and by written procedures on 18 August, 29 September 2006 and on 14 August 2007, revised according to the comments of the European Commission (ref.:AGRI 004597of 06.02.2007, AGRI 022644 of 05.09.07 and AGRI 029995 of 22.11 07.) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 I.1 PROGRAMME COMPLEMENT....................................................................... 5 I.2 THE MANAGING AUTHORITY for ARDOP.................................................. 6 I.2.1 General description......................................................................................... 6 I.2.2 The MANAGING AUTHORITY in Hungary................................................ 6 I.2.3 Monitoring ...................................................................................................... 6 I.2.4 Financial Management and Control Arrangements ........................................ 6 I.2.5 Monitoring the capacities................................................................................ 6 I.3 THE PAYING AUTHORITY............................................................................. 6 I.4 THE INTERMEDIATE BODY .......................................................................... 6 I.5 THE FINAL BENEFICIARIES......................................................................... -

El Ő Terjeszt

E L Ő T E R J E S Z T É S Komló Város Önkormányzat Képviselő-testületének 2013. november 28-án tartandó ülésére Az előterjesztés tárgya: A Komló Kistérségi Végrehajtási-Ellenőrzési Hatósági Társulás 2012. évi és 2013.I. félévi beszámolója Iktatószám: 3645-2/2013. A napirend előterjesztője: dr. Vaskó Ernő címzetes főjegyző Az előterjesztést készítette: Udvardyné Hafner Anita vezető-főtanácsos, dr. Vikor László hatósági és adóiroda vezetője Az előterjesztést véleményező bizottságok a hatáskör megjelölésével: Bizottság Hatáskör Pénzügyi, Jogi és Ellenőrzési bizottság SZMSZ 1. sz. melléklet IV/C.) 28. pont Határozatot és előterjesztést Kapják: Bodolyabér Község Önkormányzata, 7394 Bodolyabér, Petőfi u. 21. Egyházaskozár Község Önkormányzata, 7347 Egyházaskozár, Fő tér 1. Hegyhátmaróc Község Önkormányzata, 7348 Hegyhátmaróc, Kolozsvári u. 18. Hosszúhetény Község Önkormányzata, 7694 Hosszúhetény, Fő u. 170 Kárász Község Önkormányzata, 7333 Kárász, Petőfi u. 36. Köblény Község Önkormányzata, 7334 Köblény, Kossuth tér 1. Liget Község Önkormányzata, 7331 Liget, József A. u. 7. Magyaregregy Község Önkormányzata, 7332 Magyaregregy, Kossuth u. 73. Magyarhertelend Község Önkormányzata, 7394 Magyarhertelend, Kossuth u. 46. Magyarszék Község Önkormányzata, 7496 Magyarszék, Kossuth u. 33. Mánfa Község Önkormányzata, 7304 Mánfa, Fábián B. u. 58. Máza Község Önkormányzata, 7351 Máza, Kossuth u. 24. Mecsekpölöske Község Önkormányzata, 7305 Mecsekpölöske, Szabadság u. 21. Szalatnak Község Önkormányzata, 7334 Szalatnak, Béke u. 4. Szászvár Község Önkormányzata, 7349 Szászvár, Május 1. tér 1. Szárász Község Önkormányzata, 7184 Szárász, Hunyadi u. 10. Tófű Község Önkormányzata, 7348 Tófű, Kossuth u. 58. Vékény Község Önkormányzata, 7333 Vékény, Fő u. 43. Oroszló Község Önkormányzata, 7370 Oroszló, Petőfi u. 29. Gerényes Község Önkormányzata, 7362 Gerényes, Kossuth u. 22. Kisvaszar Község Önkormányzat 7381 Kisvaszar, Albert I. -

Hegyháti Járás

HEGYHÁTI JÁRÁS valamint BIKAL és OROSZLÓ JÁRÁSI TÜKÖR Készült az Integrált térségi gyermekprogramok EFOP-1.4.2-16 c. pályázat beadásához 2016 1 TARTALOM…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….2 Vezetői összefoglaló……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…..…..3 1. A Járás általános jellemzése…………………………………………………………………………………………..…….…..7 2. A Járás népességének társadalmi gazdasági jellemzői………………………………………………………….…12 2.1. Demográfiai adatok……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……12 2.2. Végzettség…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………..17 2.3. Foglalkoztatás………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….….19 2.4. Munkanélküliség……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…...20 2.5. Segélyezési helyzetkép……………………………………………………………………………………….………………..…27 3. A gyerekes családok szegénységi kockázata és helyzete .....………………………………………………..….31 4. Lakás, lakhatás egyéb infrastrukturális ellátottság………………………………………….……………….……..36 5. Szolgáltatások a járás településein ………………………………………………………………………………….…..…40 5.1. Humán szolgállérhetősége és jellemzői ………………………………………………………………………..…..……40 5.2. Egészségügyi szolgáltatások elérhetősége és jellemzői …………………………………………………..………49 5.3. Közoktatási intézmények és szolgáltatások ……………………………………………………………………….……53 5.3.1 Óvoda ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………......53 5.3.2 Általános iskola ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………57 5.3.2.1 Iskolai teljesítmény ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..61 5.3.2.2. Továbbtanulás, lemorzsolódás ……………………………………………………………………………………….…..63 -

50 Abod Aggtelek Ajak Alap Anarcs Andocs Apagy Apostag Arka

Bakonszeg Baks Baksa Anarcs Andocs Abod Balajt Apagy Balaton Apostag Aggtelek Ajak Arka Balsa Alap Barcs Basal 50 Biharkeresztes Biharnagybajom Battonya Bihartorda Biharugra Bikal Biri Bekecs Botykapeterd Bocskaikert Bodony Bucsa Bodroghalom Buj Belecska Beleg Bodrogkisfalud Bodrogolaszi Benk sa Bojt Cece Bokor Beret Boldogasszonyfa Cered Berkesz Berzence Boldva Besence Csaholc Bonnya Beszterec Csaroda Borota 51 Darvas Csehi Csehimindszent Dunavecse Csengele Demecser Csenger Ecseg Csengersima Derecske Ecsegfalva Detek Egeralja Devecser Egerbocs Egercsehi Doba Egerfarmos Csernely Doboz Egyek Csipkerek Dombiratos Csobaj Csokonyavisonta Encs Encsencs Endrefalva Enying Eperjeske Dabrony Damak 52 Erk Geszt Furta Etes Gige Golop Fancsal Farkaslyuk Fegyvernek Gadna Gyugy Garadna Garbolc Fiad Gelej Fony Gemzse Halmaj 53 Hangony Hantos Hirics Hobol Hedrehely Hegymeg Homrogd Hejce Hencida Hencse Ibafa Heresznye Igar Igrici Iharos Ilk Kaba Imola Inke Iregszemcse Irota Heves Istenmezeje Hevesaranyos Kamond 54 Kamut Kisdobsza Kelebia Kemecse Kapoly Kemse Kishuta Kenderes Kiskinizs Kaposszerdahely Kengyel Kiskunmajsa Karancsalja Kerta Kismarja Karancskeszi Kispirit Kevermes Karcag Karcsa Kisar Karos Kisasszond Kistelek Kisasszonyfa Kaszaper Kisbajom Kisvaszar Kisberzseny Kisszekeres Kisbeszterce 55 Liget Kocsord Krasznokvajda Litka Kokad Kunadacs Litke Kunbaja Kuncsorba Lucfalva Kunhegyes Lulla Kunmadaras Madaras Kompolt Kupa Magosliget Kutas Magy Magyaregregy Lad Magyarhertelend Magyarhomorog Lak Magyarkeszi Magyarlukafa Laskod Magyarmecske Magyartelek -

A B a L I G E T - a B a L I N G

Familienbuch der katholischen Pfarrgemeinden A B A L I G E T - A B A L I N G und H E T V E H E L Y – H E T F E H E L L im Komitat Baranya/Ungarn 1757 - 1895 1895 - 1919 von Elmar Rosa 2. erweiterte Auflage 2012 - 2 - Das in der Schriftenreihe zur donauschwäbischen Herkunftsforschung erschienene Familienbuch, Band 77, der katholischen Pfarrgemeinden Abaliget-Abaling und Hetvehely-Hetfehel im Komitat Baranya/Ungarn (Ausgabe 1998) wurde erweitert. Die erweiterte Auflage enthält zusätzlich die Zeitspanne 1895-1919. - 3 - I N H A L T S V E R Z E I C H N I S Teil I (1757-1895) Vorwort 4, 5 1. Kurzer Abriss der verkarteten Orte 6 2. Die Zuordnung der Ortschaften 8 3. Datenerfassung 9 4. Datenaufbereitung 4.1. Schwierigkeiten und Besonderheiten 9 4.2. Festlegungen und Einschränkungen 10 4.3. Matrikelbuchführer 10 4.4. Genealogische Zeichen und Abkürzungen 11 4.5. Abkürzungen der Ortsnamen 11 4.6. Das Lautalphabet 11 5. Gliederung des Familienbuches 12 6. Quellen- und Literaturangaben 12 7. Die Familien und Einzelpersonen 13 8. Anhang 8.1. Familien mit deutschen Namen, die nicht erfasst wurden 575 8.2. Unvollständige Einträge 579 8.3. Register der verschiedenen Schreibweisen der Nachnamen 580 8.4. Madjarisierte Nachnamen 589 8.5. Register der Ehrfrauen, über deren Eltern keine Angaben vorliegen 590 8.6. Register der Taufpaten, deren Namen im Abschnitt 7 nicht vorkommen 627 8.7. Register der Ortsnamen 633 8.8. Verzeichnis der gefallenen der beiden Weltkriege 643 8.9. Die Familien in den kirchlichen Seelenlisten von 1767 644 8.10. -

Magyarország Települései (Összesen:3154)

Magyarország települései (Összesen:3154) Név | osm_id ---------------------+--------- Aba | 1402808 Abádszalók | 1325119 Abaliget | 1606342 Abasár | 1417304 Abaújalpár | 1317821 Abaújkér | 1317762 Abaújlak | 1391023 Abaújszántó | 1280990 Abaújszolnok | 1391024 Abaújvár | 1280983 Abda | 1440629 Abod | 1317773 Abony | 1319915 Ábrahámhegy | 1078516 Ács | 1027798 Acsa | 1375466 Acsád | 1131678 Acsalag | 1483311 Ácsteszér | 1027789 Adács | 1417484 Ádánd | 1367959 Adásztevel | 1078626 Adony | 1420598 Adorjánháza | 1078447 Adorjás | 575113 Ág | 575221 Ágasegyháza | 1130325 Ágfalva | 1491394 Aggtelek | 1317826 Agyagosszergény | 1483469 Ajak | 1453538 Ajka | 1078501 Aka | 1027803 Akasztó | 1130332 Alacska | 1428656 Alap | 1403023 Alattyán | 1323442 Albertirsa | 1323261 Alcsútdoboz | 1370220 Aldebrő | 1417305 Algyő | 1025064 Alibánfa | 1357192 Almamellék | 575120 Almásfüzitő | 1608474 Almásháza | 1359703 Almáskamarás | 1026175 Almáskeresztúr | 575252 Álmosd | 1452163 Alsóberecki | 1317353 Alsóbogát | 1367878 Alsódobsza | 1439559 Alsógagy | 1317829 Alsómocsolád | 575341 Alsónána | 1501297 Alsónémedi | 214783 Alsónemesapáti | 1359601 Alsónyék | 1501299 Alsóörs | 1078460 Alsópáhok | 1358253 Alsópetény | 1373920 Alsórajk | 1358085 Alsóregmec | 1432030 Alsószenterzsébet | 1311790 Alsószentiván | 1403110 Alsószentmárton | 575196 Alsószölnök | 1131427 Alsószuha | 1418035 Alsótelekes | 1607539 Alsótold | 1370520 Alsóújlak | 1131460 Alsóvadász | 1391174 Alsózsolca | 1440883 Ambrózfalva | 1025076 Anarcs | 1452611 Andocs | 1367841 Andornaktálya | 1418116