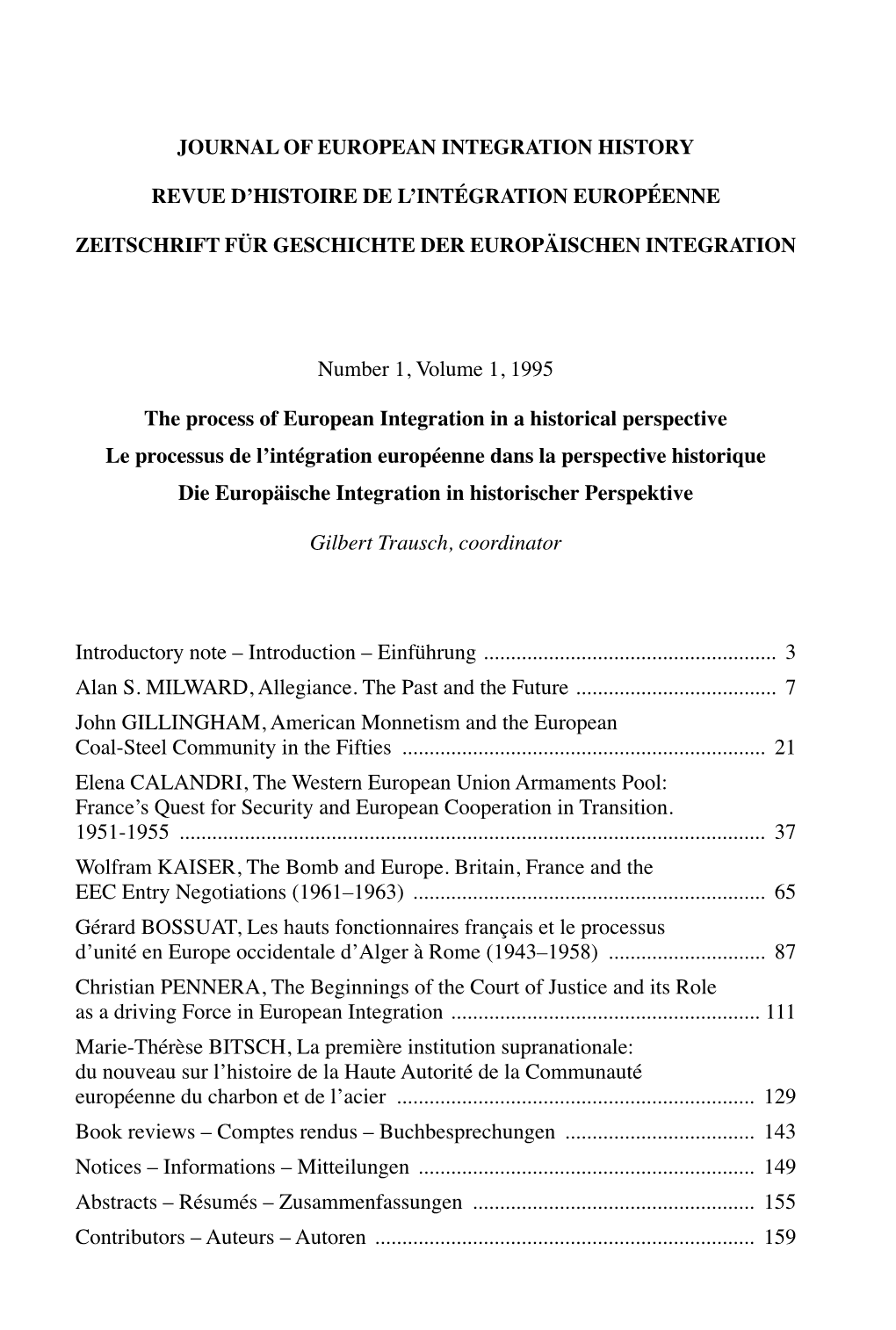

1 Journal of European Integration History Revue D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Positive Effect of Political Dynasties: the Case of France's 1940 Enabling

PRELIMINARY VERSION: PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE OR CITE WITHOUT THE AUTHORS’ PERMISSION A Positive Effect of Political Dynasties: the case of France’s 1940 enabling act* Jean Lacroixa, Pierre-Guillaume Méona, Kim Oosterlincka,b Abstract The literature on political dynasties in democracies usually considers dynasties as a homogenous group and points out their negative effects. By contrast, we argue that political dynasties may differ according to their origin and that democratic dynasties - dynasties whose founder was a defender of democratic ideals - show a stronger support for democracy than other dynasties. This conclusion is based on the analysis of the vote by the French parliament on July 10, 1940 of an enabling act that granted full power to Marshall Philippe Pétain, thereby ending the Third French republic and aligning France with Nazi Germany. Using individual votes and newly-collected data from the biographies of the members of parliament, we observe that members of a democratic dynasty had a 7.6 to 9.0 percentage points higher probability to oppose the act than members of other political dynasties or elected representatives belonging to no political dynasty. Suggestive evidence points to the pro-democracy environment of democratic dynastic politicians as the main driver of this effect. Keywords: Autocratic reversals, democratic dynasties, voting behavior. JEL classification: D72, H89, N44. *We thank Toke Aidt, Francois Facchini, Katharina Hofer, and Tommy Krieger as well as participants at the Interwar Workshop - London School of Economics and Political Science, at the Meeting of the European Public Choice Society in Rome, at the Silvaplana Workshop in Political Economy, and at the Beyond Basic Questions Workshop for comments and suggestions. -

Fonds Edmond Giscard D'estaing (1896-1986)

Fonds Edmond Giscard d'Estaing (1896-1986). Répertoire numérique détaillé de la sous-série 775AP (775AP/1-775AP/91). Établi par Pascal Geneste, conservateur en chef du patrimoine. Première édition électronique. Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2018 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_056869 Cet instrument de recherche a été rédigé dans le système d'information archivistique des Archives nationales. Ce document est écrit en français. Conforme à la norme ISAD(G) et aux règles d'application de la DTD EAD (version 2002) aux Archives nationales. 2 Archives nationales (France) Préface « Le passé, pays lointain que l’on visite avec ferveur et mélancolie, nous inspire souvent un sentiment d’infinie nostalgie. » Valéry Giscard d’Estaing à Emmanuel Hamel (2 novembre 1971) 3 Archives nationales (France) Sommaire Fonds Edmond Giscard d'Estaing. 8 Papiers personnels. 11 1896-1983 11 Scolarité et études. 11 Études supérieures de lettres. 12 Papiers militaires. 12 Cartes et papiers d'état-civil. 12 Inspection des Finances. 12 Ministère des Colonies. 13 Compagnie d’assurances Le Phénix. 13 Dessins. 13 Mairie et conseil municipal de Chanonat. 13 Indochine. 14 Chambre de commerce internationale. 14 Présidence du comité national français. 14 Congrès de la Chambre de commerce internationale. 14 Institut de France. 14 Candidature et élection. 14 Élection. 15 Activités. 15 Société du tunnel routier sous le Mont-Blanc. 15 Fonctionnement. 15 Administration. 15 Correspondance. 15 Construction. 16 Manifestations. 16 « Società per il Traforo del Monte Bianco ». 16 Exploitation. 16 Notes et documentation. 17 « De la Savoie au pays d’Aoste par le tunnel du Mont-Blanc ». -

PROCÉDURES DE SAUVEGARDE DES ENTREPRISES (Décret No 2005-1677 Du 28 Décembre 2005)

o Quarante-deuxième année. – N 182 A ISSN 0298-296X Mercredi 8 octobre 2008 BODACCBULLETIN OFFICIEL DES ANNONCES CIVILES ET COMMERCIALES ANNEXÉ AU JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Standard......................................... 01-40-58-75-00 DIRECTION DES JOURNAUX OFFICIELS Annonces....................................... 01-40-58-77-56 Renseignements documentaires 01-40-58-79-79 26, rue Desaix, 75727 PARIS CEDEX 15 Abonnements................................. 01-40-58-79-20 www.journal-officiel.gouv.fr (8h30à 12h30) Télécopie........................................ 01-40-58-77-57 BODACC “A” Ventes et cessions - Créations d’établissements Procédures collectives Procédures de rétablissement personnel Avis relatifs aux successions Avis aux lecteurs Les autres catégories d’insertions sont publiées dans deux autres éditions séparées selon la répartition suivante Modifications diverses..................................... $ BODACC “B” Radiations ......................................................... # Avis de dépôt des comptes des sociétés .... BODACC “C” Avis aux annonceurs Toute insertion incomplète, non conforme aux textes en vigueur ou bien illisible sera rejetée Banque de données BODACC servie par les sociétés : Altares-D&B, EDD, Experian, Optima on Line, Groupe Sévigné-Payelle, Questel, Tessi Informatique, Jurismedia, Pouey International, Scores et Décisions, Les Echos, Creditsafe, Coface services et Cartegie. Conformément à l’article 4 de l’arrêté du 17 mai 1984 relatif à la constitution et à la commercialisation d’une banque de données télématique des informations contenues dans le BODACC, le droit d’accès prévu par la loi no 78-17 du 6 janvier 1978 s’exerce auprès de la Direction des Journaux officiels. Le numéro : 2,20 € Abonnement. − Un an (arrêté du 28 décembre 2007 publié au Journal officiel le 30 décembre 2007) : France : 351 €. Pour l’expédition par voie aérienne (outre-mer) ou pour l’étranger : paiement d’un supplément modulé selon la zone de destination, tarif sur demande Tout paiement à la commande facilitera son exécution . -

Robert Buron

ter aoGt t950- JOURNAL OFFICIEL DU TERRITOIRE DU TOOO 691 ART. 5. - L'article 35 du décret suwisé du 24 Le ministre des f!nances et des affaires économiques, Juillet 1947 est "lIlQdifié comme ;;uit : MAURiCE-PETSCHE. « Apnès avis du conseil supérieur de la fonction pu Le ministre dJt blll1get, blique, une commission administrative peut être dis Edgar FAURE. soute dans la forme prévue pour sa constitution. Il Le ministre de l'éducation nationale, est alors procédé, dans le délai de deux lIlQis et selon André MORICE. la procédure ordinaire, à la constitutiQn d'une llOuvelie commission, dont le renouvellement ",st soumis aux Le ministre des travaux publics, conditions déterminées aux articles 7 et 10 ci-dessus ". des traltSJ10rts et du tourisme, Maurice BouROÈs-MAUNOURY" ART. 6" - Le premier alinéa de l'article 43 du dé Le ministre de l'industrie et da cOmmerco, cret du 24 juillet 1947 susvisé est complété par les Jean-Marie LOUVEL. dispositions suivantes: « ". Toutefois, la durée du mandat de ces membres Le ministre de l'agt'cu!tllre, pourra être modifiée par ar~êté du ministre intéressé, Pierre Pl'LlMLIN. de façon à aSSlUrer le renouvellement des comités tech Le ministre de la France d'outre.mer" niques intéressant un service ou grQupe de services dé Paul COSTE-FLORET. terminés dans le délai maximum de six mois suivant le Le ministre dJt travail et de la sécurité SOClale, renowellement, dans les conditions fixées" aux ar Paul c BACON. ticles 7 et 10 du présent décr",t, des commissions ad Le miNs/re' de la recollStraction et de l'u;I'bfJJ1isme, ministratives paritaires correspondant auxdits s",rvices ». -

Vichy Against Vichy: History and Memory of the Second World War in the Former Capital of the État Français from 1940 to the Present

Vichy against Vichy: History and Memory of the Second World War in the Former Capital of the État français from 1940 to the Present Audrey Mallet A Thesis In the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne December 2016 © Audrey Mallet, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Audrey Mallet Entitled: Vichy against Vichy: History and Memory of the Second World War in the Former Capital of the État français from 1940 to the Present and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. G. LeBlanc External Examiner Dr. E. Jennings External to Program Dr. F. Chalk Examiner Dr. D. Peschanski Examiner Dr. C. Claveau Thesis Co-Supervisor Dr. N. Ingram Thesis Co-Supervisor Dr. H. Rousso Approved by: Dr. B. Lorenzkowski, Graduate Program Director December 5, 2016 Dr. A. Roy, Dean, Faculty of Arts & Science Abstract Vichy against Vichy: History and Memory of the Second World War in the Former Capital of the État français from 1940 to the Present Audrey Mallet, Ph.D. Concordia University & Paris I Panthéon Sorbonne, 2016 Following the June 22, 1940 armistice and the subsequent occupation of northern France by the Germans, the French government left Paris and eventually established itself in the city of Vichy. -

Deuxieme Partie : Les Realites D U Pouvoir

467 DEUXIEME PARTI: E S REALITELE S D U POUVOIR " En acceptant, non sans courage, la di- rection des affaires à 1'heure présente, le Parti socialiste risque d'avoir- as à sumer de lourdes responsabilités demain, celles, peut-être misela somneilen de f deRépublique."(la Propos tenu M.Def-par ferre Robertà Buron, 1956,le lo mai cf. R,Buron, op.cit., p. 187,) 469 La situation parlementaire précair Gouvernemenu ed Frone d t t répu- blicain n'apparaissai comms pa facteun t u e paralysie d r débue c n ee t d'année 1956. Elle pouvait au contraire être un encouragement décisif à l'action: seul le mouvement était susceptible de naintenir en place un ministère dont la situation est comparable à celle d'un enfant apprenant à fairbicyclettla ede e sans roues stabilisatrices. Le contexte national et international est favorable aux initiati- s veplule s s diverses a Francl : e peut enfin être engagée dan procesn u s - sus global de décolonisation pacifique, elle peut participer de manière décisiv renforcemenu ea a détentel e d t , profitanet , esson so re d écot - nomique, assurer à l'intérieu plue un sr grande justice sociale. L'au- dace, l'esprit de décision trouveront matière à application en tous do- maines, c'es e voel électeurs t t donn ude nette on i un ée qu s majoritx éau forces de gauche et ont sanctionné la majorité conservatrice de la secon- de Législature. Certes attendain o , t Pierre Mollety Mendês-FranceGu t . fu e c t e , Maidirectioe un s n socialist Gouvernemenu ed présentait-elle n t s epa des avantages compensant ceux qu'aurait offert directioe un s n radicale? La S.F.I.O souffr e pluu divisions n o . -

The Negro in France

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Black Studies Race, Ethnicity, and Post-Colonial Studies 1961 The Negro in France Shelby T. McCloy University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation McCloy, Shelby T., "The Negro in France" (1961). Black Studies. 2. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_black_studies/2 THE NEGRO IN FRANCE This page intentionally left blank SHELBY T. McCLOY THE NEGRO IN FRANCE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS Copyright© 1961 by the University of Kentucky Press Printed in the United States of America by the Division of Printing, University of Kentucky Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 61-6554 FOREWORD THE PURPOSE of this study is to present a history of the Negro who has come to France, the reasons for his coming, the record of his stay, and the reactions of the French to his presence. It is not a study of the Negro in the French colonies or of colonial conditions, for that is a different story. Occasion ally, however, reference to colonial happenings is brought in as necessary to set forth the background. The author has tried assiduously to restrict his attention to those of whose Negroid blood he could be certain, but whenever the distinction has been significant, he has considered as mulattoes all those having any mixture of Negro and white blood. -

The Commodification of French Intellectual Culture, 1945-1990

From Ideas to Icons: The Commodification of French Intellectual Culture, 1945-1990 By Hunter K. Martin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: August 9, 2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Laird Boswell, Professor, History Mary Louise Roberts, Professor, History Suzanne Desan, Professor, History Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, Professor, History Richard Staley, Professor, History of Science © Copyright by Hunter K. Martin 2012 All Rights Reserved i Table of Contents Abbreviations ii Tables and Illustrations iii Introduction Commodification: A New Concept for the History of Intellectual Culture 1 Part I From Inspiration to Implantation: The Origins of Maisons de la Culture 24 Chapter 1 Local Cultural Centers and the “Great Intellectual Struggle of Our Time” 24 Chapter 2 The Commercialization of Maisons de la Culture in Paris and Grenoble 65 Part II Off the Page and onto the Stage: The Making and Marketing of Intellectual Culture at Maisons de la Culture 106 Chapter 3 A Considerable Track Record: Encounters with Intellectual Culture in Paris and Grenoble 106 Chapter 4 Maisons de la Culture and the Creation of Demand 141 Part III Appropriations and Parallel Evolutions 174 Chapter 5 Out with the Old, in with the Pompidou 174 Chapter 6 A Virtuous Cycle: Intellectual Culture on Television and in Journals 207 Conclusion Intellectual “Engagement” -

Bulletin Officiel Spécial N° 8 Du 10-09-2015

Bulletin officiel spécial n° 8 du 10-09-2015 Annexe Classement des lycées professionnels – rentrée 2016 CATEGORIE NUMERO ACADEMIE NOM COMMUNE FINANCIERE ETABLISSEMENT 2016 AIX-MARSEILLE 0132569X LP EMILE ZOLA AIX-EN-PROVENCE 2 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130170P LP VAUVENARGUES AIX-EN-PROVENCE 4 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130006L LP GAMBETTA (COURS) AIX-EN-PROVENCE 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130012T LP PERDIGUIER ARLES 4 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130171R LP CHARLES PRIVAT ARLES 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130013U LP GUSTAVE EIFFEL AUBAGNE 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0840041N LP MARIA CASARES AVIGNON 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0840042P LP ROBERT SCHUMAN AVIGNON 4 AIX-MARSEILLE 0840939P LP RENE CHAR AVIGNON 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0840044S LP VICTOR HUGO CARPENTRAS 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0840113S LP ALEXANDRE DUMAS CAVAILLON 4 AIX-MARSEILLE 0040007L LP ALPHONSE BEAU DE ROCHAS DIGNE-LES-BAINS 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0050005D LP ALPES ET DURANCE EMBRUN 2 AIX-MARSEILLE 0050008G LP PAUL HERAUD GAP 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0050009H LP SEVIGNE GAP 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130025G LP ETOILE (DE L') GARDANNE 2 AIX-MARSEILLE 0132276D LP PIERRE LATECOERE ISTRES 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0040011R LP LOUIS MARTIN BRET MANOSQUE 4 AIX-MARSEILLE 0132319A LP MAURICE GENEVOIX MARIGNANE 2 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130033R LP LOUIS BLERIOT MARIGNANE 2 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130055P LP CHATELIER (LE) MARSEILLE 3E ARRONDISSEMENT 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130172S LP LEONARD DE VINCI MARSEILLE 7E ARRONDISSEMENT 3 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130071G LP COLBERT MARSEILLE 7E ARRONDISSEMENT 4 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130062X LP FREDERIC MISTRAL MARSEILLE 8E ARRONDISSEMENT 4 AIX-MARSEILLE 0130063Y LP LEAU (BD) MARSEILLE 8E ARRONDISSEMENT 3 AIX-MARSEILLE -

Voir La Table En

BAI — 23 — BAS B BAIL (Prorogation de). — Voy. Loyers — de Paris et des Pays-Bas. — Voy. Natio et fermages, § 16. nalisations, § 10. — de la Réunion. — Voy. Territoires d'outre- mer, § 12. BANQUE DE LA RÉUNION (Rôle — à tout va. — Voy. Jeux, § 2. social de la), Observations y relatives, voy. — de l’Union parisienne. — Voy. Nationali Budget de l'exercice 4946, § 2 (Colonies), Dis sations, § 10. cussion générale. BANQUES D’AFFAIRES. — Proposi BANQUES. tion de loi de M. Charles Barangé «t plusieurs de ses collègues tendant à fixer le statut des banques — d’affaires. — Voy. Nationalisations, §§ 20, d’affaires, présentée à l’Assemblée Nationale 26. Constituante le 19 avril 1946 (2e séance) (ren — d'Afrique occidentale. — Voy. Nationa voyée à la Commission des finances), n° 1120. lisations, § 18. — Territoires d'outre-mer, § 38. — d’Algérie. — Voy. Nationalisations, §§21, BARAQUES (Livraisons de), Observa 24, 28. tions y relatives, voy. Budget de Vexercice 4946, — de France (Convention avec la). — Voy. § 2 (Reconstruction et Urbanisme), Discus Nationalisation, §§7, 16. sion générale. — de I’Economie Nationale. — Voy. Natio nalisations, § 5. — grandes. — Voy. Nationalisations, §§ 5,7. BARRAGES. — de Bort. — Voy. S. N. C. F., § 3. — — d’intérêt public. — Voy. Territoires Pêche fluviale. d’outre-mer, § 12. — internationale pour la reconstruction et le développement. — Voy. Traités et conventions, BASES AÉRONAVALES (Recons si. truction de nos), Observations y relatives, — de Madagascar. — Voy. Territoires d'outre- voy. Budget de Vexercice 4946, § 2 (Dépenses mer, §§ 8, 38. — Nationalisations, § 19. militaires), A rm é es. — nationalisées. ^ Voy. Nationalisations, §25. BASES DE CALCUL. — Voy. Pensions — ouverte. — Voy. Jeux, § 2. et retraites, § 7. -

LES GOUVERNEMENTS ET LES ASSEMBLÉES PARLEMENTAIRES SOUS LA Ve RÉPUBLIQUE

LES GOUVERNEMENTS ET LES ASSEMBLÉES PARLEMENTAIRES SOUS LA Ve RÉPUBLIQUE - 2 - AVERTISSEMENT La liste des ministères établie par la présente brochure fait suite à celles figurant : 1° dans le tome I du Dictionnaire des parlementaires français de 1871 à 1940 ; 2° dans la publication séparée, intitulée « Ministères de la France de 1944 à 1958 ». Elle couvre la période du 8 janvier 1959 au 31 juillet 2004. Outre la liste nominative des membres des Gouvernements, on trouvera les renseignements relatifs : - à l’élection des Présidents de la République ; - aux dates des élections aux Assemblées parlementaires et à la composition politique de celles-ci, ainsi qu’aux dates des sessions du Parlement ; - aux lois d’habilitation législative prises en application de l’article 38 de la Constitution ; - à la mise en jeu de la responsabilité gouvernementale ; - aux réunions du Congrès ; Dans les notes en bas de page de la liste nominative des membres des Gouvernements, les formules utilisées correspondent aux cas suivants : * Devient : changement des fonctions gouvernementales * Nommé : légère modification des fonctions gouvernementales et changement de titre * Prend le titre de : changement de titre sans changement des fonctions gouvernementales. Le texte de la présente brochure a été établi par le Secrétariat général de la Présidence et le service de la Communication. - 3 - CONNAISSANCE DE L’ASSEMBLÉE 2 LES GOUVERNEMENTS ET LES ASSEMBLÉES PARLEMENTAIRES SOUS LA Ve RÉPUBLIQUE 1958-2004 (Données au 31 juillet) ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE - 4 - TOUS DROITS RÉSERVÉS. La présente publication ne peut être fixée, par numérisation, mise en mémoire optique ou photocopie, ni reproduite ou transmise, par moyen électronique ou mécanique ou autres, sans l’autorisation préalable de l’Assemblée nationale. -

CONCOURS GÉNÉRAL Palmarès Académique

CONCOURS GÉNÉRAL Session 2013 Palmarès académique AIX-MARSEILLE ACCESSIT(S) 1er accessit Dissertation philosophique série L Mademoiselle Louise GRENUT du Lycée général et technologique Paul Cézanne à Aix-en-Provence terminale L Professeure : Madame MARTIN 5ème accessit Géographie Mademoiselle Léa MOUTARD du Lycée polyvalent d'Altitude à Briançon première ES Professeur : Monsieur AGASSE MENTION(S) mention Artisanat et métiers d'art option arts de la pierre Monsieur Brian FARNIER du Lycée professionnel les Alpilles à Miramas Term pro Professeur : Monsieur SUCAL mention Restauration approfondissement « service et Monsieur Jean-Philippe CHILINI de la Section d'enseignement professionnel du Lycée des métiers hôtelier régional commercialisation » à Marseille Term pro Professeure : Madame DOMINIQUE WAILLE mention Sciences et technologies industrielles et du Monsieur Tom VOISIN du Lycée polyvalent Jean-Henri Fabre à Carpentras développement durable terminale STI2 Professeur : Monsieur ANAYA CONCOURS GÉNÉRAL Session 2013 Palmarès académique ALGERIE MENTION(S) mention Arabe Mademoiselle Annia ABTOUT du Lycée international Alexandre Dumas à Alger terminale S Professeur : Monsieur KERKOUR CONCOURS GÉNÉRAL Session 2013 Palmarès académique ALLEMAGNE ACCESSIT(S) 1er accessit Allemand Monsieur Félix GRIMBERG du Lycée français à Düsseldorf terminale S Professeure : Madame LANGENSCHEID 1er accessit Géographie Monsieur Axel VALENTIN du Lycée Jean Renoir à Munich première S Professeure : Madame DUBESSET 2ème accessit Allemand Monsieur Marcus WOELFFER du