Illusions, Musicality and the Live Dancing Body Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internet Killed the B-Boy Star: a Study of B-Boying Through the Lens Of

Internet Killed the B-boy Star: A Study of B-boying Through the Lens of Contemporary Media Dehui Kong Senior Seminar in Dance Fall 2010 Thesis director: Professor L. Garafola © Dehui Kong 1 B-Boy Infinitives To suck until our lips turned blue the last drops of cool juice from a crumpled cup sopped with spit the first Italian Ice of summer To chase popsicle stick skiffs along the curb skimming stormwater from Woodbridge Ave to Old Post Road To be To B-boy To be boys who snuck into a garden to pluck a baseball from mud and shit To hop that old man's fence before he bust through his front door with a lame-bull limp charge and a fist the size of half a spade To be To B-boy To lace shell-toe Adidas To say Word to Kurtis Blow To laugh the afternoons someone's mama was so black when she stepped out the car B-boy… that’s what it is, that’s why when the public the oil light went on changed it to ‘break-dancing’ they were just giving a To count hairs sprouting professional name to it, but b-boy was the original name for it and whoever wants to keep it real would around our cocks To touch 1 ourselves To pick the half-smoked keep calling it b-boy. True Blues from my father's ash tray and cough the gray grit - JoJo, from Rock Steady Crew into my hands To run my tongue along the lips of a girl with crooked teeth To be To B-boy To be boys for the ten days an 8-foot gash of cardboard lasts after we dragged that cardboard seven blocks then slapped it on the cracked blacktop To spin on our hands and backs To bruise elbows wrists and hips To Bronx-Twist Jersey version beside the mid-day traffic To swipe To pop To lock freeze and drop dimes on the hot pavement – even if the girls stopped watching and the street lamps lit buzzed all night we danced like that and no one called us home - Patrick Rosal 1 The Freshest Kids , prod. -

Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2011 Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance Julia A. Fenton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Motor Control Commons Recommended Citation Fenton, Julia A., "Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance" (2011). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1436 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Principles of Movement Control that Affect Choreographers’ Instruction of Dance Julia Fenton Preface The purpose of this paper is to inform choreographers of different motor control and skill learning principles that affect instruction of dance and choreography as well as provide a resource for choreographers to make rehearsals more productive. In order to accomplish this task, I adapted the information presented in three main texts, written by Schmidt and Wrisberg, Schmidt and Lee, and Fairbrother, in order for it to be useful to choreographers. I have included dance examples rather than sport examples in order for the choreographer to more easily relate to the information. The in-text citations in this paper were kept to a minimum in order for it to be read more easily. -

Mark III Owners Manual

MESA-BOOGIE MARK III OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS MESA ENGINEERING CONGRATULATIONS! You've just become the proud owner of the world's finest guitar amplifier. When people come up to compliment you on your tone, you can smile knowingly ... and hopefully you'll tell them a little about us! This amplifier has been designed, refined and constructed to deliver maximum musical performance of any style, in any situation. And in order to live up to that tall promise, the controls must be very powerful and sophisticated. But don't worry! Just by following our sample settings, you'll be getting great sounds immediately. And as you gain more familiarity with the Boogie's controls, it will provide you with much greater depth and more lasting satisfaction from your music. THREE MODES For approximately twelve years, the evolution of the guitar amplifier has largely been pioneered by MESA-Boogie. The Original Mark I Boogie was the first amplifier to offer successful lead enhancement. Then the Mark II Boogie was the first amplifier to introduce footswitching between lead and rhythm. Now your new Mark III offers three footswitchable modes of operation: Rhythm 1, Rhythm 2 and Lead. Rhythm 1 is primarily for playing bright and sparkling clean (although a little crunch is available by running the Volume at 10). You might think of Rhythm 1 as "the Fender mode”. Rhythm 2 is mainly for crunch chords, chunking metal patterns and some blues (but low settings of the Volume 1 will produce an alternate clean sound that is very fat and warm). Think of Rhythm 2 as "the Marshall mode". -

Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics

Smith ScholarWorks Dance: Faculty Publications Dance 6-24-2013 “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Tomé, Lester, "“Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics" (2013). Dance: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs/5 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Dance: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] POSTPRINT “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Dance Chronicle 36/2 (2013), 218-42 https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2013.792325 This is a postprint. The published article is available in Dance Chronicle, JSTOR and EBSCO. Abstract: Alicia Alonso contended that the musicality of Cuban ballet dancers contributed to a distinctive national style in their performance of European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. A highly developed sense of musicality distinguished Alonso’s own dancing. For the ballerina, this was more than just an element of her individual style: it was an expression of the Cuban cultural environment and a common feature among ballet dancers from the island. In addition to elucidating the physical manifestations of musicality in Alonso’s dancing, this article examines how the ballerina’s frequent references to music in connection to both her individual identity and the Cuban ballet aesthetics fit into a national discourse of self-representation that deems Cubans an exceptionally musical people. -

Walt Disney and the Power of Music James Bohn

Libri & Liberi • 2018 • 7 (1): 167–180 169 The final part of the book is the epilogue entitled “Surviving Childhoodˮ, in which the author shares her thoughts on the importance of literature in childrenʼs lives. She sees literature as an opportunity to keep memories, relate stories to pleasant times from the past, and imagine things which are unreachable or far away. For these reasons, children should be encouraged to read, which will equip them with the skills necessary to create their own associations with reading and creating their own worlds. Finally, The Courage to Imagine demonstrates how literature can influence childrenʼs thinking and help them cope with the world around them. Dealing with topics present in everyday life, such as ethnic diversity, fear, bullying, or empathy, and offering examples of child heroes who overcome their problems, this book will be engaging to teachers and students, as well as experts in the field of childrenʼs literature. Its simple message that through reading children “can escape the adult world and imagine alternativesˮ (108) should be sufficient incentive for everybody to immerse themselves in reading and to start imagining. Josipa Hotovec Walt Disney and the Power of Music James Bohn. 2017. Music in Disneyʼs Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 294 pp. ISBN 978-1-4968-1214-8 DOI: 10.21066/carcl.libri.2018-07(01).0008 “The essence of a Disney animated feature is not drawn by pencil […]. Rather, it is written in notes”, states James Bohn in the conclusion to his 2017 book Music in Disney’s Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book (201). -

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

February 12 – 16, 2016

February 12 – 16, 2016 danceFilms.org | Filmlinc.org ta b l e o F CONTENTS DA N C E O N CAMERA F E S T I VA L Inaugurated in 1971, and co-presented with Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center since 1996 (now celebrating the 20th anniversary of this esteemed partnership), the annual festival is the most anticipated and widely attended dance film event in New York City. Each year artists, filmmakers and hundreds of film lovers come together to experience the latest in groundbreaking, thought-provoking, and mesmerizing cinema. This year’s festival celebrates everything from ballet and contemporary dance to the high-flying world of trapeze. ta b l e o F CONTENTS about dance Films association 4 Welcome 6 about dance on camera Festival 8 dance in Focus aWards 11 g a l l e ry e x h i b i t 13 Free events 14 special events 16 opening and closing programs 18 main slate 20 Full schedule 26 s h o r t s p r o g r a m s 32 cover: Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers in Kinetic Molpai, ca. 1935 courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance festival archives this Page: The Dance Goodbye ron steinman back cover: Feelings are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer courtesy estate of warner JePson ABOUT DANCE dance Films association dance Films association and dance on camera board oF directors Festival staFF Greg Vander Veer Nancy Allison Donna Rubin Interim Executive Director President Virginia Brooks Liz Wolff Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Paul Galando Brian Cummings Joanna Ney Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Vice President and Chair of Ron -

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

Preparing Musicians Making New Sound Worlds

PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Compiled by Orlando Musumeci PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Proceedings of the SEMINAR of the COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya – Barcelona – SPAIN 5-9 JULY 2004 Compiled by Orlando Musumeci Published by the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya Catalan texts translated by Mariam Chaib Babou (except for Rosset i Llobet) Spanish texts translated by Orlando Musumeci (except for Estrada, Mauleón and Rosset i Llobet) Copyright © ISME. All rights reserved. Requests for reprints should be sent to: International Society for Music Education ISME International Office P.O. Box 909 Nedlands 6909, WA, Australia T ++61-(0)8-9386 2654 / F ++61-(0)8-9386-2658 [email protected] ISBN: 0-9752063-2-X ISME COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN DIANA BLOM [email protected] University of Western Sydney – AUSTRALIA PHILEMON MANATSA [email protected] Morgan Zintec – ZIMBABWE ORLANDO MUSUMECI (Chair) [email protected] Institute of Education – University of London – UK Universidad de Quilmes – Universidad de Buenos Aires – Conservatorio Alberto Ginastera – ARGENTINA INOK PAEK [email protected] University of Sheffield – UK VIGGO PETTERSEN [email protected] Stavanger University College – NORWAY SUSAN WHARTON CONKLING [email protected] Eastman School of Music – USA GRAHAM BARTLE (Special Advisor) [email protected] -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

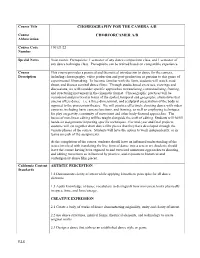

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art.