President's Message

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Necessary Chicanery : Operation Kingfisher's

NECESSARY CHICANERY: OPERATION KINGFISHER’S CANCELLATION AND INTER-ALLIED RIVALRY Gary Followill Z3364691 A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters by Research University of New South Wales UNSW Canberra 17 January 2020 1 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Australia's Global University Surname/Family Name Followill Given Name/s GaryDwain Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar MA Faculty AOFA School HASS Thesis Title Necessary Chicanery: Operation Kingfisher'scancellation and inter-allied rivalry Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis examines the cancellation of 'Operation Kingfisher' (the planned rescue of Allied prisoners of war from Sandakan, Borneo, in 1945) in the context of the relationship of the wartime leaders of the United States, Britain and Australia and their actions towards each other. It looks at the co-operation between Special Operations Australia, Special Operations Executive of Britain and the US Officeof Strategic Services and their actions with and against each other during the Pacific War. Based on hithertounused archival sources, it argues that the cancellation of 'Kingfisher' - and the failure to rescue the Sandakan prisoners - can be explained by the motivations, decisions and actions of particular British officers in the interplay of the wartime alliance. The politics of wartime alliances played out at both the level of grand strategy but also in interaction between officers within the planning headquarters in the Southwest Pacific Area, with severe implications for those most directly affected. Declaration relating to disposition of project thesis/dissertation I hereby grant to the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here afterknow n, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

Hall's Manila Bibliography

05 July 2015 THE RODERICK HALL COLLECTION OF BOOKS ON MANILA AND THE PHILIPPINES DURING WORLD WAR II IN MEMORY OF ANGELINA RICO de McMICKING, CONSUELO McMICKING HALL, LT. ALFRED L. McMICKING AND HELEN McMICKING, EXECUTED IN MANILA, JANUARY 1945 The focus of this collection is personal experiences, both civilian and military, within the Philippines during the Japanese occupation. ABAÑO, O.P., Rev. Fr. Isidro : Executive Editor Title: FEBRUARY 3, 1945: UST IN RETROSPECT A booklet commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of the University of Santo Tomas. ABAYA, Hernando J : Author Title: BETRAYAL IN THE PHILIPPINES Published by: A.A. Wyn, Inc. New York 1946 Mr. Abaya lived through the Japanese occupation and participated in many of the underground struggles he describes. A former confidential secretary in the office of the late President Quezon, he worked as a reporter and editor for numerous magazines and newspapers in the Philippines. Here he carefully documents collaborationist charges against President Roxas and others who joined the Japanese puppet government. ABELLANA, Jovito : Author Title: MY MOMENTS OF WAR TO REMEMBER BY Published by: University of San Carlos Press, Cebu, 2011 ISBN #: 978-971-539-019-4 Personal memoir of the Governor of Cebu during WWII, written during and just after the war but not published until 2011; a candid story about the treatment of prisoners in Cebu by the Kempei Tai. Many were arrested as a result of collaborators who are named but escaped punishment in the post war amnesty. ABRAHAM, Abie : Author Title: GHOST OF BATAAN SPEAKS Published by: Beaver Pond Publishing, PA 16125, 1971 This is a first-hand account of the disastrous events that took place from December 7, 1941 until the author returned to the US in 1947. -

Howzat! Get Your Wool in the Baggy Green

ISSUE 73 DECEMBER 2017 PROFIT FROM WOOL INNOVATION www.wool.com HOWZAT! GET YOUR WOOL IN THE BAGGY GREEN 10 38 56 MERINO LEAVES WILD DOG RETURNING TO THE MARINA EXCLUSION FENCING THE FAMILY FARM www.wool.com/btb 8 MERINO ON SUMMIT 34 MERINO LIFETIME OF EVEREST PRODUCTIVITY PROJECT EDITOR Richard Smith E [email protected] OFF ON CONTRIBUTING WRITER -FARM -FARM Lisa Griplas 4 Get your wool in the baggy green! 32 Merinos o©er flexible production fit E [email protected] 5 Gondoliers of Venice wearing wool 33 Tas case study: Merinos push profits up Australian Wool Innovation Limited A L6, 68 Harrington St, The Rocks, Growers at centre of Devold’s marketing Merino Lifetime Productivity update Sydney NSW 2000 6 34 GPO Box 4177, Sydney NSW 2001 Merino on Mount Everest Influencing the gender ratio of lambs P 02 8295 3100 8 36 E [email protected] W wool.com AWI Helpline 1800 070 099 9 Merino for snowboarding 37 Tax deductibility of shelterbelts SUBSCRIPTION 10 Merino in round-the-world yacht race 38 Wild dog exclusion fencing booklet Beyond the Bale is available free. To subscribe contact AWI 12 National Geographic features wool 40 Fox control programs P 02 8295 3100 E [email protected] 13 Yoga apparel in Japan 41 Rabbits numbers reduced by RHDV1 K5 Beyond the Bale is published by Australian Wool Innovation Ltd (AWI), a company 14 Merino weather resistant fabric 42 Worm egg counts funded by Australian woolgrowers and the Australian Government. AWI’s goal is to help 15 Merineo swaddling bags for newborns 44 AWI’s breech flystrike strategy increase the demand for wool by actively selling Australian wool and its attributes 16 Chinese brand showcases Aussie farm 45 Breech flystrike prevention publications through investments in marketing, innovation and R&D – from farm to fashion and interiors. -

Sheep AI Programs from the Executive Editor

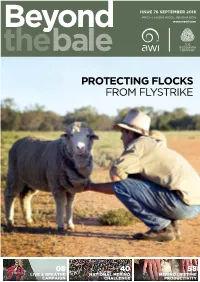

ISSUE 76 SEPTEMBER 2018 PROFIT FROM WOOL INNOVATION www.wool.com PROTECTING FLOCKS FROM FLYSTRIKE 08 40 58 LIVE & BREATHE NATIONAL MERINO MERINO LIFETIME CAMPAIGN CHALLENGE PRODUCTIVITY 14 HURN & FYFE 62 DROUGHT RESOURCES BACK FIBRE OF FOOTBALL FOR WOOLGROWERS EXECUTIVE EDITOR Richard Smith OFF ON E [email protected] -FARM -FARM A AWI Marketing and Communications L6, 68 Harrington St, The Rocks, Sydney NSW 2000 4 WoolPoll 2018 38 Lifetime Ewe Management case study GPO Box 4177, Sydney NSW 2001 40 National Merino Challenge 2018 P 02 8295 3100 8 AWI’s new ‘live & breathe’ campaign E [email protected] W wool.com 9 Peak performance from Black Diamond 42 Australian Rural Leadership Program AWI Helpline 1800 070 099 10 Jenna completes her run for bums 43 Next generation on the horizon SUBSCRIPTION Beyond the Bale is available free. 12 Leading sportswear brand ashmei 44 Queensland wild dog coordinators To subscribe contact AWI P 02 8295 3100 E [email protected] 13 Particle Fever slam dunks with wool 45 My exclusion fence is built, now what? Beyond the Bale is published by Australian 14 Fibre of Football 46 SA aerial baiting receives support Wool Innovation Ltd (AWI), a company Wild dogs in the USA funded by Australian woolgrowers and the 15 Emma Hawkins at home with Jeanswest 47 Australian Government. AWI’s goal is to help 48 2018 Flystrike RD&E Technical Update increase the demand for wool by actively 16 Wool Week Australia selling Merino wool and its attributes through 18 Scanlan Collective’s love for Merino wool 50 Performance of blowfly & lice treatments investments in marketing, innovation and R&D – from farm to fashion and interiors. -

THIRTY YEARS with FLYING ARTS – 1971 to 2001 Chapter 1

1 FROM RIVER BANKS TO SHEARING SHEDS: THIRTY YEARS WITH FLYING ARTS – 1971 to 2001 Chapter 1: Introduction This thesis traces the history of a unique Queensland art school, which began as ‘Eastaus’ (for Eastern Australia) in 1971 when Mervyn Moriarty, its founder, learned to fly a small plane in order to take his creative art school to the bush. In 1974 the name was changed to ‘The Australian Flying Arts School’; in 1994 it became ‘Flying Arts Inc.’ To avoid confusion the popular name ‘Flying Arts’ is used throughout the study. The thesis will show that when creative art (experimental art where the artist relies on his subjective sensibility), came to Brisbane in the 1950s, its dissemination by Moriarty throughout Queensland in the 1970s was a catalyst which brought social regeneration for hundreds of women living on rural properties and in large and small regional towns throughout Queensland. The study will show that through its activities the school enhanced the lives of over six thousand people living in regional Queensland and north-western New South Wales.1 Although some men were students, women predominated at Flying Arts workshops. Because little is known about country women in rural social organizations this study will focus on women, and their growing participation within the organization, to understand why they flocked to Moriarty’s workshops, and why creative art became an important part of so many lives. The popularity of the workshops, and the social interaction they supplied for so many, is a case study for Ross’s argument -

Building Our Brand Need for Speed

QUEENSLAND BUILDING OUR BRAND NEW CAMPAIGN PROMOTES OUR SERVICES TO VETERANS NEED FOR SPEED RAEMUS ROVER PROGRAM A THRILLING SUCCESS THEN. NOW. ALWAYS. 100 YEARS OF THE ROYAL AUSTRALIAN AIR FORCE MEASURING SUCCESS EVALUATION SHOWS TRUE BENEFITS OF TROJAN’S TREK EDITION 01, 2021 // THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE RETURNED & SERVICES LEAGUE OF AUSTRALIA (QUEENSLAND BRANCH) inside Edition 01 2021 RSL NEWS STAFF & ASSOCIATES 32 Returned & Services League of Australia (Queensland Branch) ABN 79 902 601 713 State President Tony Ferris State Deputy President Wendy Taylor State Vice President Bill Whitburn OAM Administration PO Box 629, Spring Hill, Qld, 4004 T: 07 3634 9444 F: 07 3634 9400 E: [email protected] W: www.rslqld.org Advertising Peter Scruby 14 E: [email protected] 26 Editor RSL Queensland E: [email protected] Content Coordinator Meagan Martin | iMedia Corp Regular Features Graphic & Editorial Design Rhys Martin | iMedia Corp Printing & Distribution Printcraft W: www.printcraft.com.au 04 President’s Message 14 THEN. NOW. ALWAYS. RSL Queensland In 2021 we celebrate 100 years of the 05 CEO’s Message current membership: 32,031 Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Queensland RSL News average Take a look back at the contribution distribution: 33,000 the service has made in Australia and 10 News Bulletin around the world. Submissions: Editorial and photographic contributions are welcome. Please contact 43 Mates4Mates the editor for guidelines. Preference will be 26 PROMOTING OUR given to electronic submissions that adhere to word limits and are accompanied by high SERVICES TO VETERANS 72 RSL Mateship resolution photos. Originals of all material Research shows the majority of our should be retained by contributors and only Defence family doesn’t realise the copies sent to Queensland RSL News. -

Atlantic Books

ATLANTIC BOOKS JULY – DECEMBER 2021 Contents Recent Highlights 2 Atlantic Books: Fiction 5 Atlantic Books: Non-Fiction 9 Corvus 33 Grove Press 47 Allen & Unwin: Fiction 55 Allen & Unwin: Non-Fiction 59 Allen & Unwin Australia: Distribution Titles 71 Export: Key Editions 77 Sales, Publicity & Rights 78 Index 81 Bestselling Backlist 86 Recent Highlights Atlantic’s bestselling and critically acclaimed titles from the past twelve months. The Cat and The The Girl from The Mystery of City Widow Hills Charles Dickens Nick Bradley Megan Miranda A.N. Wilson 9781786499912 • Paperback • 9781838950750 • Paperback • 9781786497932 • Paperback • £8.99 £8.99 £9.99 The Natural The New Class The Nothing Health Service War Man Isabel Hardman Michael Lind Catherine Ryan Howard 9781786495921 • Paperback • 9781786499578 • Paperback • 9781786496614 • Paperback • £9.99 £8.99 £8.99 2 Open Parisian Lives Pilgrims Johan Norberg Deirdre Bair Matthew Kneale 9781786497192 • Paperback • 9781786492685 • Paperback • 9781786492395 • Paperback • £9.99 £10.99 £8.99 Three Little Why the Why We Can’t Truths Germans Do it Sleep Eithne Shortall Better Ada Calhoun 9781786496201 • Paperback • John Kampfner 9781611854664 • Paperback • £8.99 9781786499783 • Paperback • £8.99 £9.99 3 4 Atlantic Books Fiction Atlantic Fiction has a reputation for publishing bold, innovative writing from around the world. Our Autumn 2021 list includes a funny and original debut about the unintentional consequences of anxiety; a translated literary thriller about betrayal and murder in the global fertility market; and the paperback of Bryan Washington’s critically acclaimed debut Memorial. 5 *Stop Press* We Play Ourselves Jen Silverman Like a cross between Shelia Heti’s How Should A Person Be? and Lily King’s Writers & Lovers, this is a wildly entertaining debut novel of female rage, self-sabotage, the pursuit of fame and the costs of artistic ambition. -

The Whyalla – a Historical Journey

The Whyalla – A Historical Journey When the original HMAS WHYALLA was launched at the Whyalla Shipyard in 1941, the proud shipbuilders of the day would have thought it inconceivable that more than 50 years later their first ship would still be serving, albeit a very different role. And it would have been just as incredulous to have suggested that the final resting place would be 2 kilometres inland and 2 metres off the ground. But, in Whyalla, the unbelievable happened. The HMAS WHYALLA (1941 – 1946), later to become The Rip (1947 – 1984), and now known affectionately as The WHYALLA, was removed from the sea in February 1987 up the same slipway, now disused, that gave it birth, and transported through the BHP plant and across a saltbush landscape to be set down on foundations adjacent to the city’s northern highway entrance. The WHYALLA is the focal point of a nationally unique attraction which includes the restored ship and museum building (Whyalla Maritime Museum) and the Whyalla Visitor Centre. The museum opened on October 29, 1988, with the Tourist Centre opening some 10 months earlier on December 23, 1987. Total cost of establishing the complex was $1.3m. Although the purchase price of the ship was just $5,000 it cost in excess of $560,000 to remove it from the sea and set it down on its specially designed foundations. Meanwhile, back to Saturday, February 14, 1987 – the day The WHYALLA was due to start its journey from the BHP Harbour. Several hundred onlookers were ready, television crews had flown from Adelaide, and the many official photographers and other media were in place to see the ship edged back up the slipway. -

Catalogue 208 MAY 2018

1 Catalogue 208 MAY 2018 Extremely hard to find complete in their boxes 208/196. (4110) Bean, C.E.W. Official History of WW1 in 12 Vols. AWM various editions. Various editions in varying colours and conditions all complete in original boxes and some with original 'butcher's paper' dust wrappers (page 17) 2 Glossary of Terms (and conditions) INDEX Returns: books may be returned for refund within 7 days and only if not as described in the catalogue. NOTE: If you prefer to receive this catalogue via email, let us know on in- [email protected] CATEGORY PAGE My Bookroom is open each day by appointment – preferably in the afternoons. Give me a call. American Civil War 3 Abbreviations: 8vo =octavo size or from 140mm to 240mm, ie normal size book, 4to = quarto approx 200mm x 300mm (or coffee table size); d/w = dust wrapper; Aviation 4 pp = pages; vg cond = (which I thought was self explanatory) very good condition. Other dealers use a variety including ‘fine’ which I would rather leave to coins etc. Illus = illustrations (as opposed to ‘plates’); ex lib = had an earlier life in library Espionage 6 service (generally public) and is showing signs of wear (these books are generally 1st editions mores the pity but in this catalogue most have been restored); eps + end papers, front and rear, ex libris or ‘book plate’; indicates it came from a Military Biography 8 private collection and has a book plate stuck in the front end papers. Books such as these are generally in good condition and the book plate, if it has provenance, ie, is linked to someone important, may increase the value of the book, inscr = Military General 9 inscription, either someone’s name or a presentation inscription; fep = front end paper; the paper following the front cover and immediately preceding the half title page; biblio: bibliography of sources used in the compilation of a work (important Naval 11 to some military historians as it opens up many other leads). -

October – November 2005

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 ListeningListeningTHE OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2005 VOL. 28 No.10 PostPost The official journal of THE RETURNED & SERVICES LEAGUE OF AUSTRALIA POSTAGE PAID SURFACE WA Branch Incorporated • PO Box Y3023 Perth 6832 • Established 1920 AUSTRALIA MAIL Back row: Gorden Pelham, Pat Strevett, Shirley Duckworth, Henk Doelman, Len Elliot, Shirley Elliott, Shirley Altham, Neil Bishop, Elsie Bishop. Front row: Mary Eggers, Marjorie Clarke, Horace Smith, Bill Jenks, Joe Pearce, Mrs Duckworth, Arthur Duckworth, Jessie Altham. Left to right: Deb Clarke, Marjorie Clarke and Lisa Clarke. CommemorationCommemoration ofof 60th60th AnniversaryAnniversary ofof VPVP DayDay Monday the 15th of August 2005 When the parade reached the RSL was the 60th Anniversary of VP Throughout Australia, communities Memorial Hall, Allan Zweck Day – Victory in the Pacific. welcomed everyone and paid tribute to those people from the Throughout Australia, communities gathered to commemorate the anniversary district, who had either served in the gathered to commemorate the war or had been manpowered for anniversary of end the Second securing freedom. School students World War, when Japan announced of end the Second World War, when Japan laid wreaths in memory of those its surrender to the allies. who lost their lives and a plaque, A National VP Day Ceremony was announced its surrender to the allies. commemorating the VP Day held on the Parade ground at the anniversary, was unveiled by Mrs War Memorial in Canberra, which Pat Strevett and Mrs Mary Eggers. was attended by the Ambassador of Australian Flags, which were town was Lake Grace, who’s Lions The parade then adjourned to the The Bush Japan, Hideaki Ueda who sent a distributed free, courtesy of Club realised the importance of Shire Hall, which was decorated in Wireless letter to State Headquarters Australia Post. -

(1986). Royal Thick 8Vo. Orig. Cloth

1 ADAMS, Douglas. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. A trilogy in four parts. ... London: (1986). Royal thick 8vo. Orig. cloth. Dustjacket. (590pp.). Former owner’s name on front fly‑leaf, otherwise fine. $60 2 ADAMS, Richard. Watership Down. (Sydney): Angus & Robertson, (1974). 8vo. Orig. illust. cloth. Gilt. Dustjacket. (viii,414pp.). With a col. fold. map at end. 1st Aust. edition. Fine. $115 3 AGNEW, Max. Silks and Sulkies. The Complete Book of Australian and New Zealand Harness Racing. Sydney: Doubleday, (1986). 4to. Orig. cloth. Dustjacket. (320pp.). Profusely illustrated in both colour and b/w. $65 4 AGRICOLA, Georgius. (George BAUER). De Re Metallica. Transl. from the First Latin Edition of 1556; with biographical introduction, annotations and appendices upon the Development of Mining Methods, Metallurgical Processes, Geology, Mineralogy & Mining Law from the earliest times to the 16th Century; by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover. Publ. for the Translators, London 1912. Thick folio. Orig. full parchment. (4,xxxii,642pp.). Illustrated throughout with line reproductions of the original woodcuts which show the processes referred to in the text. First Edition in English. In unusually fine condition. Extremely rare. NOTE: When Herbert Hoover was a senior in Stanford University and Lou Henry, whom he afterwards married, was a freshman, they had access to the celebrated geological library of Professor J.C. Branner. Among the books was a copy of the most important mining book ever written, namely Georgius Agricola’s “De Re Metallica” written in Latin, and published in 1556. When some years later, in 1903, the Hoovers had the opportunity to purchase a copy of the original edition, they decided to translate and publish an English version.