AP Chemistry NOTES 14-1 TYPES of CHEMICAL BONDS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 5. Chemical Bonding

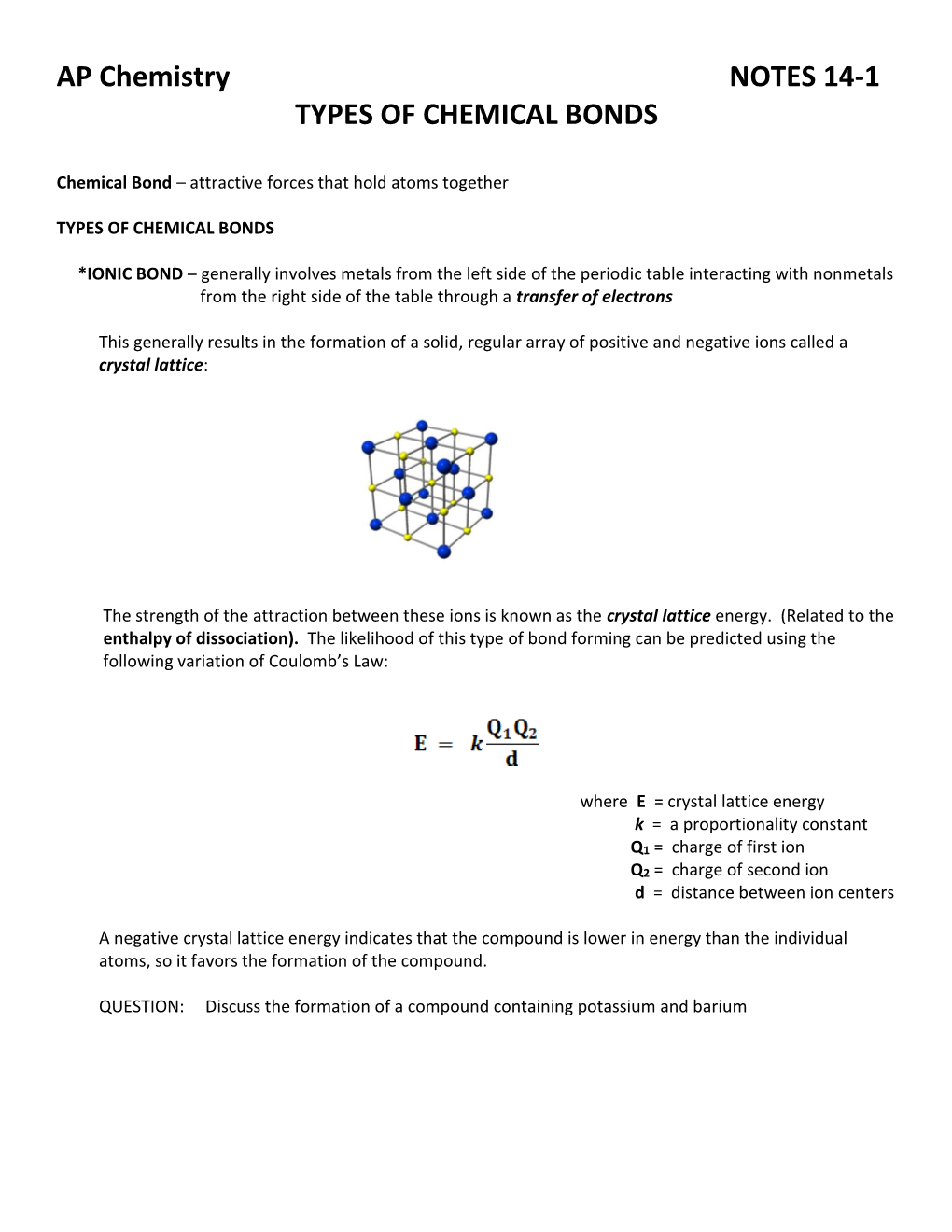

5. Chemical Bonding: The Covalent Bond Model 5.1 The Covalent Bond Model Almost all chemical substances are found as aggregates of atoms in the form of molecules and ions produced through the reactions of various atoms of elements except the noble-gas elements which are stable mono-atomic gases. Chemical bond is a term that describes the attractive force that is holding the atoms of the same or different kind of atoms in forming a molecule or ionic solid that has more stability than the individual atoms. Depending on the kinds of atoms participating in the interaction there seem to be three types of bonding: Gaining or Losing Electrons: Ionic bonding: Formed between many ions formed by metal and nonmetallic elements. Sharing Electrons: Covalent bonding: sharing of electrons between two atoms of non-metals. Metallic Bonding: sharing of electrons between many atoms of metals. Ionic Compounds Covalent Compounds Metallic Compounds 1. Metal and non-meal Non-metal and non-meal Metal of one type or, element combinations. elements combinations. combinations of two or metal elements combinations. 2. High melting brittle Gases, liquids, or waxy, low Conducting, high melting, crystalline solids. melting soft solids. malleable, ductile crystalline solids. 3. Do not conduct as a solid Do not conduct electricity at Conduct electricity at solid but conducts electricity any state. and molten states. when molten. 4. Dissolved in water produce Most are soluble in non-polar Insoluble in any type of conducting solutions solvents and few in water. solvents. (electrolytes) and few These solutions are non- are soluble in non-polar conducting (non- solvents. -

Chapter 11: Solutions: Properties and Behavior

Chapter 11: Solutions: Properties and Behavior Learning Objectives 11.1: Interactions between Ions • Be able to estimate changes in lattice energy from the potential energy form of Coulomb’s Law, Q Q Cation Anion , in which is lattice energy, is a proportionality constant, is the charge on E = k E k QCation r the cation, Q is the charge on the anion, and r is the distance between the centers of the ions. Anion 11.2: Energy Changes during Formation and Dissolution of Ionic Compounds • Understand the concept of lattice energy and how it is a quantitative measure of stability for any ionic solid. As lattice energy increases, the stability of the ionic solid increases. • Be able to estimate changes in lattice energy from the potential energy form of Coulomb’s Law, Q Q Cation Anion , in which is lattice energy, is a proportionality constant, is the charge on E = k E k QCation r the cation, Q is the charge on the anion, and r is the distance between the centers of the ions. Anion • Be able to determine lattice energies using a Born-Haber cycle, which is a Hess’s Law process using ionization energies, electron affinities, and enthalpies for other atomic and molecular properties. • Be able to describe a molecular view of the solution process using Hess’s Law: 1. Solvent → Solvent Particles where ∆Hsolvent separation is endothermic. 2. Solute → Solute Particles where ∆Hsolute separation is endothermic. 3. Solvent Particles + Solute Particles → Solution where ∆Hsolvation can be endo- or exothermic. 4. ∆Hsolution = ∆Hsolvent separation + ∆Hsolute separation + ∆Hsolvation This is a Hess’s Law thinking process, and ∆Hsolvation is called the ∆Hhydration when the solvent is water. -

Fundamental Studies of Early Transition Metal-Ligand Multiple Bonds: Structure, Electronics, and Catalysis

Fundamental Studies of Early Transition Metal-Ligand Multiple Bonds: Structure, Electronics, and Catalysis Thesis by Ian Albert Tonks In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2012 Defended December 6th 2011 ii 2012 Ian A Tonks All Rights Reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely fortunate to have been surrounded by enthusiastic, dedicated, and caring mentors, colleagues, and friends throughout my academic career. A Ph.D. thesis is by no means a singular achievement; I wish to extend my wholehearted thanks to everyone who has made this journey possible. First and foremost, I must thank my Ph.D. advisor, Prof. John Bercaw. I think more so than anything else, I respect John for his character, sense of fairness, and integrity. I also benefitted greatly from John’s laissez-faire approach to guiding our research group; I’ve always learned best when left alone to screw things up, although John also has an uncanny ability for sensing when I need direction or for something to work properly on the high-vac line. John also introduced me to hiking and climbing in the Eastern Sierras and Owens Valley, which remain amongst my favorite places on Earth. Thanks for always being willing to go to the Pizza Factory in Lone Pine before and after all the group hikes! While I never worked on any of the BP projects that were spearheaded by our co-PI Dr. Jay Labinger, I must also thank Jay for coming to all of my group meetings, teaching me an incredible amount while I was TAing Ch154, and for always being willing to talk chemistry and answer tough questions. -

Chemical Forces Understanding the Relative Melting/Boiling Points of Two

Chapter 8 – Chemical Forces Understanding the relative melting/boiling points of two substances requires an understanding of the forces acting between molecules of those substances. These intermolecular forces are important for many additional reasons. For example, solubility and vapor pressure are governed by intermolecular forces. The same factors that give rise to intermolecular forces (e.g. bond polarity) can also have a profound impact on chemical reactivity. Chemical Forces Internuclear Distances and Atomic Radii There are four general methods of discussing interatomic distances: van der Waal’s, ionic, covalent, and metallic radii. We will discuss the first three in this section. Each has a unique perspective of the nature of the interaction between interacting atoms/ions. Van der Waal's Radii - half the distance between two nuclei of the same element in the solid state not chemically bonded together (e.g. solid noble gases). In general, the distance of separation between adjacent atoms (not bound together) in the solid state should be the sum of their van der Waal’s radii. F F van der Waal's radii F F Ionic Radii – Ionic radii were discussed in Chapter 4 and you should go back and review that now. One further thing is worth mentioning here. Evidence that bonding really exists and is attractive can be seen in ionic radii. For all simple ionic compounds, the ions attain noble gas configurations (e.g. in NaCl the Na+ ion is isoelectronic to neon and the Cl- ion is isoelectronic to argon). For the sodium chloride example just given, van der Waal’s radii would predict (Table 8.1, p. -

Assembly of Multi-Flavored Two-Dimensional Colloidal Crystals† Cite This: Soft Matter, 2017, 13,5397 Nathan A

Soft Matter View Article Online PAPER View Journal | View Issue Assembly of multi-flavored two-dimensional colloidal crystals† Cite this: Soft Matter, 2017, 13,5397 Nathan A. Mahynski, *a Hasan Zerze,b Harold W. Hatch, a Vincent K. Shena and Jeetain Mittal *b We systematically investigate the assembly of binary multi-flavored colloidal mixtures in two dimensions. In these mixtures all pairwise interactions between species may be tuned independently. This introduces an additional degree of freedom over more traditional binary mixtures with fixed mixing rules, which is anticipated to open new avenues for directed self-assembly. At present, colloidal self-assembly into non-trivial lattices tends to require either high pressures for isotropically interacting particles, or the introduction of directionally anisotropic interactions. Here we demonstrate tunable assembly into a plethora of structures which requires neither of these conditions. We develop a minimal model that defines a three-dimensional phase space containing one dimension for each pairwise interaction, then employ various computational techniques to map out regions of this phase space in which the system self-assembles into these different morphologies. We then present a mean-field model that is capable of reproducing these results for size-symmetric mixtures, which reveals how to target different structures by tuning pairwise interactions, solution stoichiometry, or both. Concerning particle size asymmetry, we find Received 19th May 2017, that domains in this model’s phase space, corresponding to different morphologies, tend to undergo a Accepted 30th June 2017 continuous ‘‘rotation’’ whose magnitude is proportional to the size asymmetry. Such continuity enables DOI: 10.1039/c7sm01005b one to estimate the relative stability of different lattices for arbitrary size asymmetries. -

CHAPTER 20: Lattice Energy

CHAPTER 20: Lattice Energy 20.1 Introduction to Lattice Energy 20.2 Born-Haber Cycles 20.3 Ion Polarisation 20.4 Enthalpy Changes in Solutions Learning outcomes: (a) explain and use the term lattice energy (∆H negative, i.e. gaseous ions to solid lattice). (b) explain, in qualitative terms, the effect of ionic charge and of ionic radius on the numerical magnitude of a lattice energy. (c) apply Hess’ Law to construct simple energy cycles, and carry out calculations involving such cycles and relevant energy terms, with particular reference to: (i) the formation of a simple ionic solid and of its aqueous solution. (ii) Born-Haber cycles (including ionisation energy and electron affinity). (d) interpret and explain qualitatively the trend in the thermal stability of the nitrates and carbonates in terms of the charge density of the cation and the polarisability of the large anion. (e) interpret and explain qualitatively the variation in solubility of Group II sulfates in terms of relative magnitudes of the enthalpy change of hydration and the corresponding lattice energy. 20.1 Introduction to Lattice Energy What is lattice energy? 1) In a solid ionic crystal lattice, the ions are bonded by strong ionic bonds between them. These forces are only completely broken when the ions are in gaseous state. 2) Lattice energy(or lattice enthalpy) is the enthalpy change when one mole of solid ionic lattice is formed from its scattered gaseous ions. 3) Lattice energy is always negative. This is because energy is always released when bonds are formed. 4) Use sodium chloride, NaCl as an example. -

Chapter Eleven: Chemical Bonding

© Adrian Dingle’s Chemistry Pages 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012. All rights reserved. These materials may NOT be copied or redistributed in any way, except for individual class instruction. Revised August 2011 AP TOPIC 8: Chemical Bonding Introduction In the study of bonding we will consider several different types of chemical bond and some of the theories associated with them. TYPES OF BONDING INTRA INTER (Within (inside) compounds) (Interactions between the STRONG molecules of a compound) WEAK Ionic Covalent Hydrogen Bonding Dipole-Dipole London Dispersion (Metal + Non-metal) (Non-metals) (H attached to N, O or F) (Polar molecules) Forces Giant lattice of ions Discrete molecules Strong, permanent dipole Permanent dipoles (Non-polar molecules) Induced dipoles Dative or (Co-ordinate) (Electron deficient species) Discrete molecules To help distinguish the difference in strength of intra and inter bonds consider the process of boiling of water. When water boils the product is steam (gaseous water). The products are not hydrogen and oxygen. This is because the weak inter molecular forces are broken not the much stronger intra molecular forces. C:\Documents and Settings\AdrianD\My Documents\Dropbox\ADCP\apnotes08.doc Page 1 of 26 © Adrian Dingle’s Chemistry Pages 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012. All rights reserved. These materials may NOT be copied or redistributed in any way, except for individual class instruction. Revised August 2011 Intra Bonding Ionic (the transfer of electrons between atoms to form ions that form giant ionic lattices) Atoms have equal numbers of protons and electrons and consequently have no overall charge. -

The Chemistry of Alkynes

14_BRCLoudon_pgs4-2.qxd 11/26/08 9:04 AM Page 644 14 14 The Chemistry of Alkynes An alkyne is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon triple bond; the simplest member of this family is acetylene, H C'C H. The chemistry of the carbon–carbon triple bond is similar in many respects toL that ofL the carbon–carbon double bond; indeed, alkynes and alkenes undergo many of the same addition reactions. Alkynes also have some unique chem- istry, most of it associated with the bond between hydrogen and the triply bonded carbon, the 'C H bond. L 14.1 NOMENCLATURE OF ALKYNES In common nomenclature, simple alkynes are named as derivatives of the parent compound acetylene: H3CCC' H L L methylacetylene H3CCC' CH3 dimethylacetyleneL L CH3CH2 CC' CH3 ethylmethylacetyleneL L Certain compounds are named as derivatives of the propargyl group, HC'C CH2 , in the common system. The propargyl group is the triple-bond analog of the allyl group.L L HC' C CH2 Cl H2CA CH CH2 Cl L L LL propargyl chloride allyl chloride 644 14_BRCLoudon_pgs4-2.qxd 11/26/08 9:04 AM Page 645 14.1 NOMENCLATURE OF ALKYNES 645 We might expect the substitutive nomenclature of alkynes to be much like that of alkenes, and it is. The suffix ane in the name of the corresponding alkane is replaced by the suffix yne, and the triple bond is given the lowest possible number. H3CCC' H CH3CH2CH2CH2 CC' CH3 H3C CH2 C ' CH L L L L L L L propyne 2-heptyne 1-butyne H3C CH C ' C CH3 HC' C CH2 CH2 C' C CH3 L L L L 1,5-heptadiyneLL L "CH3 4-methyl-2-pentyne Substituent groups that contain a triple bond (called alkynyl groups) are named by replac- ing the final e in the name of the corresponding alkyne with the suffix yl. -

Constraint Closure Drove Major Transitions in the Origins of Life

entropy Article Constraint Closure Drove Major Transitions in the Origins of Life Niles E. Lehman 1 and Stuart. A. Kauffman 2,* 1 Edac Research, 1879 Camino Cruz Blanca, Santa Fe, NM 87505, USA; [email protected] 2 Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, WA 98109, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Life is an epiphenomenon for which origins are of tremendous interest to explain. We provide a framework for doing so based on the thermodynamic concept of work cycles. These cycles can create their own closure events, and thereby provide a mechanism for engendering novelty. We note that three significant such events led to life as we know it on Earth: (1) the advent of collective autocatalytic sets (CASs) of small molecules; (2) the advent of CASs of reproducing informational polymers; and (3) the advent of CASs of polymerase replicases. Each step could occur only when the boundary conditions of the system fostered constraints that fundamentally changed the phase space. With the realization that these successive events are required for innovative forms of life, we may now be able to focus more clearly on the question of life’s abundance in the universe. Keywords: origins of life; constraint closure; RNA world; novelty; autocatalytic sets 1. Introduction The plausibility of life in the universe is a hotly debated topic. As of today, life is only known to exist on Earth. Thus, it may have been a singular event, an infrequent event, or a common event, albeit one that has thus far evaded our detection outside our own planet. Herein, we will not attempt to argue for any particular frequency of life. -

Basic Concepts of Chemical Bonding

Basic Concepts of Chemical Bonding Cover 8.1 to 8.7 EXCEPT 1. Omit Energetics of Ionic Bond Formation Omit Born-Haber Cycle 2. Omit Dipole Moments ELEMENTS & COMPOUNDS • Why do elements react to form compounds ? • What are the forces that hold atoms together in molecules ? and ions in ionic compounds ? Electron configuration predict reactivity Element Electron configurations Mg (12e) 1S 2 2S 2 2P 6 3S 2 Reactive Mg 2+ (10e) [Ne] Stable Cl(17e) 1S 2 2S 2 2P 6 3S 2 3P 5 Reactive Cl - (18e) [Ar] Stable CHEMICAL BONDSBONDS attractive force holding atoms together Single Bond : involves an electron pair e.g. H 2 Double Bond : involves two electron pairs e.g. O 2 Triple Bond : involves three electron pairs e.g. N 2 TYPES OF CHEMICAL BONDSBONDS Ionic Polar Covalent Two Extremes Covalent The Two Extremes IONIC BOND results from the transfer of electrons from a metal to a nonmetal. COVALENT BOND results from the sharing of electrons between the atoms. Usually found between nonmetals. The POLAR COVALENT bond is In-between • the IONIC BOND [ transfer of electrons ] and • the COVALENT BOND [ shared electrons] The pair of electrons in a polar covalent bond are not shared equally . DISCRIPTION OF ELECTRONS 1. How Many Electrons ? 2. Electron Configuration 3. Orbital Diagram 4. Quantum Numbers 5. LEWISLEWIS SYMBOLSSYMBOLS LEWISLEWIS SYMBOLSSYMBOLS 1. Electrons are represented as DOTS 2. Only VALENCE electrons are used Atomic Hydrogen is H • Atomic Lithium is Li • Atomic Sodium is Na • All of Group 1 has only one dot The Octet Rule Atoms gain, lose, or share electrons until they are surrounded by 8 valence electrons (s2 p6 ) All noble gases [EXCEPT HE] have s2 p6 configuration. -

Early- Versus Late-Transition-Metal-Oxo Bonds: the Electronlc Structure of VO' and Ruo'

J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 2109-2115 2109 Early- versus Late-Transition-Metal-Oxo Bonds: The Electronlc Structure of VO' and RuO' Emily A. Cartert and William A. Goddard III* Arthur Amos Noyes Laboratory of Chemical Physics,$ California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125 (Received: July 9, 1987; In Final Form: November 3, 1987) From all-electron ab initio generalized valence bond calculations (GVBCI-SCF) on VO+ and RuO', we find that an accurate description of the bonding is obtained only when important resonance configurations are included self-consistently in the wave function. The ground state of VO+('Z-) has a triple bond similar to that of CO, with D,""(V-O) = 128.3 kcal/mol [DFptl(V-O) = 1.31 * 5 kcal/mol], while the ground state of RuO+(~A)has a double bond similar to that of Oz, with D,CS'cd(Ru-O) = 67.1 kcal/mol. Vertical excitation energies for a number of low-lying electronic states of VO+ and RuO' are also reported. These results indicate fundamental differences in the nature of the metal-oxo bond in early and late metal oxo complexes that explain the observed trends in reactivity (e.g., early metal oxides are thermodynamically stable whereas late metal oxo complexes are highly reactive oxidants). Finally, we have used these results to predict the ground states of MO' for other first-row transition-metal oxides. I. Introduction TABLE I: First-Row Transition-Metal-Oxo Bond Strengths While the electronic structure of neutral transition-metal oxides (kcal/mol)' has been examined by several authors,' the only cationic tran- metal Do(M+-O) Do(M-0) metal Do(M+-O) Do(M-0) sition-metal oxide (TMO) which has been studied with correlated 3 Mn 3 wave functions is2 CrO+. -

Organometrallic Chemistry

CHE 425: ORGANOMETALLIC CHEMISTRY SOURCE: OPEN ACCESS FROM INTERNET; Striver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry Lecturer: Prof. O. G. Adeyemi ORGANOMETALLIC CHEMISTRY Definitions: Organometallic compounds are compounds that possess one or more metal-carbon bond. The bond must be “ionic or covalent, localized or delocalized between one or more carbon atoms of an organic group or molecule and a transition, lanthanide, actinide, or main group metal atom.” Organometallic chemistry is often described as a bridge between organic and inorganic chemistry. Organometallic compounds are very important in the chemical industry, as a number of them are used as industrial catalysts and as a route to synthesizing drugs that would not have been possible using purely organic synthetic routes. Coordinative unsaturation is a term used to describe a complex that has one or more open coordination sites where another ligand can be accommodated. Coordinative unsaturation is a very important concept in organotrasition metal chemistry. Hapticity of a ligand is the number of atoms that are directly bonded to the metal centre. Hapticity is denoted with a Greek letter η (eta) and the number of bonds a ligand has with a metal centre is indicated as a superscript, thus η1, η2, η3, ηn for hapticity 1, 2, 3, and n respectively. Bridging ligands are normally preceded by μ, with a subscript to indicate the number of metal centres it bridges, e.g. μ2–CO for a CO that bridges two metal centres. Ambidentate ligands are polydentate ligands that can coordinate to the metal centre through one or more atoms. – – – For example CN can coordinate via C or N; SCN via S or N; NO2 via N or N.