Strange Tangents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Pressure Waterjet

Application Note High Pressure Waterjet A water jet is a cutting tool capable of slicing metal or other materials by using a narrow stream of water at high velocity and pressure, or a mixture of water and an abrasive substance. The process erodes the materials in the same way as water erosion found in nature but accelerated and concentrated through high pressure. It is often used in the fabrication or manufacture of parts for machinery and other industries. It is used in applications in the mining to aerospace industries where it performs operations such as cutting, shaping, carving, and reaming. The water jet is usually connected to a high-pressure water pump (Viatran supplies units at 60K PSI) where the water is then ejected from the nozzle, cutting through the material by spraying it with the jet of high-speed water. Adding suspended grit or other abrasives, such as garnet and aluminum oxide, can accelerate this process. Because the characteristics of the cutting stream can be easily modified, water jets can be used to cut materials from processed food to exotic metals. There are few materials that cannot be effectively cut with a water jet cutter. Two of these are tempered glass and certain ceramics are resistant to water jet cutting. Water jet cuts are not typically limited by the thickness of the material, and are capable of cutting materials over a foot (30 cm) thick. An important benefit of the water jet cutter is the ability to cut material without compromising the material's inherent structure. The effects of heat are minimized by the water jet. -

Proceedings of the Second U.S. Water Jet Conference Held in 1983 at the University of Missouri-Rolla

Proceedings of the Second U.S. WATER JET CONFERENCE May 24-26, 1983 Rolla, Missouri Edited by: David A. Summers and Frank F. Haston Sponsored by School of Mines & Metallurgy, University of Missouri-Rolla Published by: University of Missouri-Rolla, Rolla, Missouri 65401 The University of Missouri-Rolla has granted the WaterJet Technology Association the right to reprint, on the Association's web site, the Proceedings of the Second U.S. Water Jet Conference held in 1983 at the University of Missouri-Rolla. Please Note. This text is a scanned in version of the original. Because of some limitations in our programming the original pagination has been changed. Other than that we have tried to make the text a little more readable by increasing the spacing between paragraphs, but the text itself has been (subject to possible OCR misinterpretations) left as written. 2nd U. S. WATER JET CONFERENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS SESSION 1 - THEORETICAL Chairman: Dr. William Cooley, Terraspace, Rockville, Maryland Dimensionless Pipe Length Analysis for Jet Modulation Systems J.L. Evers, D.L. Eddingfield and J.Y. Yuh College of Engineering and Technology Southern Illinois University at Carbondale Carbondale, Illinois 62901 An Analysis of One Possibility for Pulsating a High Pressure Water Jet M. Mazurkiewicz Rock Mechanics/Explosives Research Center University of Missouri - Rolla Rolla, Missouri 65401 Standoff Distance Improvement Using Percussive Jets E.B. Nebeker Scientific Associates, Inc. Santa Monica, California The Focused Shock Technique for Producing Transient Water Jets G. Gustafsson Department of Mechanical Engineering University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado 80309 SESSION 2 - EXPERIMENTAL & EQUIPMENT Chairman: Dr. -

Manuelian Jarce 53 2017.Pdf

The Lost Throne of Queen Hetepheres from Giza: An Archaeological Experiment in Visualization and Fabrication PETER DER MANUELIAN Abstract In 1925, one of the greatest discoveries made at Giza revealed a small, unfinished chamber (labeled “G 7000 X”) more than twenty-seven meters underground, just east of the Great Pyramid. The Harvard University–Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition found there the deteriorated burial equipment, sarcophagus, and other objects be- longing to Queen Hetepheres I, presumed consort of Snefru and mother of Khufu. Since the discovery of this rare Old Kingdom royal assemblage, the thousands of small fragments have remained in storage in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Meticulous documentation allowed the excavators to reconstruct some of the queen’s furniture. However, the most exquisite piece, her “second” chair or throne, made of cedar with hundreds of faience inlays and completely gilded, was never reconstructed. This paper describes an interdisciplinary collaboration initiated by the Giza Project at Harvard University to create a full-scale reproduction of Hetepheres’s second chair in modern cedar, faience, gold, gesso, and copper. The goals for this visualization experiment were to reconstruct the excavation history, the iconog- raphy, and to document, insofar as possible, the ancient workflow the Egyptians used to construct this Old Kingdom masterpiece. The final results produced a new museum display object and research/teaching tool. Two significant features of Hetepheres’s tomb complex stand out today. One -

Tool Safeguarding and Controls'

Tool Safeguarding and Controls’ (Guidance originally developed by Yale University/Issued with permission) Tool Type Size/Style Power Potential Hazards Emergency Stopping and Shields and Other Protective Power Controls2 Guards Measures Arbor Press Bench or Manual • Caught between — crushing, limited by • Warning label Standing manual operation Band Saw / Small Bench Electric • Cutting blade —lacerations • E-stop, accessible single • Blade • Push sticks • Rotating blade pulleys — pinch points, action hand switch, or • Covered pulleys • Fence entanglement foot switch • Flying objects — eye, face, skin injuries • Anti-restart for wood Band Saw / Large Standing Electric • Cutting blade — lacerations, amputation • E-stop, accessible single • Blade plus • Smallest opening in • Rotating blade pulleys — pinch points, action hand switch, or extension if work surface entanglement foot switch needed possible . Flying objects — eye, face, skin injuries • Anti-restart for wood • Fully encased band saw wheels Bead / Shot Blaster Bench Electric • Abrasive shot — skin irritation, abrasion • E-stop, accessible single (w/ Glove box) • Rotating / moving parts —blade in fan action hand switch, or motor foot switch . Flying objects — eye, face, skin injuries • Door interlocks for large units Brake, Metal Bench or Manual • Caught between —finger crushing Bending Standing Buffer, Wheel Bench or Electric • Rotating parts — entanglement • E-stop, accessible single • Rotating shaft • Clamps for small Standing • Flying objects — eye, face, skin injuries action hand -

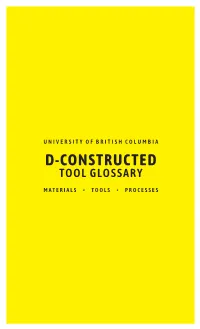

D-Constructed Tool Glossary

UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA D-CONSTRUCTED TOOL GLOSSARY MATERIALS • TOOLS • PROCESSES A 21 POLAR 23 ADDITIVE MANUFACT. 66 PROFILE SCANNER C R 18 CARTESIAN 59 ROTOMOLDING 43 CNC LATHE 44 CNC MILL S 53 CNC PRESS BRAKE 20 SCARA 54 CNC PUNCH PRESS 38 STEREOLITHOGRAPHY 55 CNC ROLLER APPARATUS (S.L.A.) 45 CNC ROUTER 25 SUBTRACTIVE MANUFACT. 56 CNC TUBE BENDER 37 SELECTIVE LASER MELTING 09 CONCEPTS (S.L.M.) 16 CUTTING TOOLS 58 SINGLE POINT FORMING (S.P.F.) D 67 STRUCTURED-LIGHT 19 DELTA 12 DEGREES OF FREEDOM T 14 TOOL PATH E 49 EDM V 57 VACUUM FORMING F 07 FOREWORDS W 27 FORMATIVE FABRICATION 48 WATER JET CUTTER 35 FUSED DEPOSITION 49 WIRE EDM MODELING (F.D.M.) 13 WORK ENVELOPE H # 31 HYBRIDS 10 2D 11 3D L 68 3D BODY SCAN 36 LAMINATED OBJECT 39 3D INK JET MANUFACTURING (L.O.M.) 12 6-DEGREES OF FREEDOM 63 LIDAR I 60 INJECTION MOLDER 61 INPUT K 15 KINEMATICS M 64 MOTION CAPTURE P 14 PATH 65 PHOTOGRAMMETRY 47 PLASMA CUTTER 03 GLOSSARY 48 WATER JET CUTTER 49 WIRE EDM 05 TABLE OF CONTENT 51 FORMING 07 FOREWORDS 53 CNC PRESS BRAKE 09 TERMS & CONCEPTS 54 CNC PUNCH PRESS 55 CNC ROLLER 10 2D 56 CNC TUBE BENDER 11 3D 57 VACUUM FORMING 12 6-DEGREES OF FREEDOM 58 SINGLE POINT FORMING 13 TOOLSPACE 59 ROTOMOLDING 14 TOOLPATH 60 INJECTION MOLDING 15 KINEMATICS 16 CARTESIAN 61 INPUT 17 G-CODE | CNC 18 CARTESIAN 63 LIDAR 19 DELTA 64 MOTION CAPTURE 20 SCARA 65 PHOTOGRAMMETRY 21 POLAR 66 PROFILE SCANNER 23 ADDITIVE 67 STRUCTURED-LIGHT 25 SUBTRACTIVE 68 3D BODY SCAN 27 FORMING 29 INPUT 71 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 31 HYBRIDS 33 ADDITIVE MANUFACT. -

Machinery for Flat Glass Processing

Machinery for Flat Glass Processing best in glass processing 1. Turn Key Solutions Facts and figures: Everything from a single source including software. Customers benefit from the only company in the flat glass machine 1961 founding year industry that can comprehensively plan and develop large projects - also thanks to the widest product range in the industry. 1 strong brand 1,300 employees 2. Excellent Service 25 sites 230 million Euros turnover (2018) Investment security and the highest availability and productivity enable the large, global LiSEC service 95 % export rate network. A contact person familiar with the local language and customs is available close to you. 7 % of turnover for R&D more than 330 patents 3. Performance through software integration Integration of the production management software and the machinery control (digitalization/Industry 4.0) allows top operation and optimization of all integrated machines or whole glass factories. Reliable processes, good quality, solid profit: LiSEC solutions Our advanced solutions generate a great cost-to-benefit The benefits: provide flat glass processors around the world with security ratio throughout the entire lifecycle of your machines and and drive in a challenging environment. systems. Over 50 years of partnership, pioneering spirit and stability Investment security due to the size of our company Customers around the world can benefit from this: be they Leading technology with a high resale value For the last 50 years, we have been working hard to experienced manufacturers or newcomers to the industry; Great cost-to-benefit ratio throughout the entire system lifecycle enable you to sustainably boost the efficiency, the system from family businesses to industrial glass processors. -

Water Jet Cutter: an Efficient Tool for Composite Product Development

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Aerospace Laboratories Institutional Repository National Conference on Scientific Achievements of SC & ST Scientists & Technologists 14–16 April 2009, National Aerospace Laboratories, Bangalore-17 Water Jet Cutter: An Efficient Tool for Composite Product Development D. Babu Rao*, D. Baskey and R.S. Rawat Advanced Composites Division, National Aerospace Laboratories, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Bangalore-560017, INDIA E-mail: *[email protected] ABSTRACT Water jet cutter is a powerful tool in the present engineering scenario which works on the principle of micro erosion occurring when large volume of water is forced through a nozzle of reduced cross section at high velocity (~Mach No: 3) and elevated pressure (~3000 bar). Water jet cutter was used to cut lumber by forestry engineer Dr. Norman Franz in 1950s.[1] Water jet cutting find applications in diverse industries from mining to aerospace, where it is used for cutting, shaping, carving and reaming. Water jet cutting has many advantages like no local heat generation, smaller kerf width hence less material wastage, faster and cheaper, higher accuracy, automation capability, and less burr and rough edge etc. Advanced Composites Division (ACD) is actively engaged in the development of various aircraft parts for on-going National Programmes like TEJAS, SARAS etc. For the development of composite parts the most important aspect is tooling. To develop a tool, one has to start with master model. The technology used in ACD for composite tooling is based on splash technique. To fabricate master models and moulds, we require templates such as base plates, master model check templates, mould-ribs, reference pad fixing location templates and mould check templates etc. -

Liner Pro II Router

800-231-8040 productionproducts.net Liner Pro II Router PRODUCT DESCRIPTION Automated Cutting of fiber glass insulation for duct liners Download the Liner Pro software for your existing duct software Dramatically improves material utilization and overall quality Both router cutting and water jet cutter options are available Liner Pro II Specifications High Speed accurate short fiber liner cutting machines and systems. Short Fiber cutting machine capabilities 1/2 inch thick liner: cut speed up to 1000 Inches/Per Min. 1 inch thick: cut speed up to 750 IPM 1 1/2 inch thick: cut speed up to 500 IMP 2 inch thick: cut speed up to 250 IMP Adding a Liner Pro II cutter to your shop will dramatically increase the productivity of your automatic duct liner processing while improving the appearance and quality of your lined duct. Sheets of Acoustic Duct liner fittings are downloaded through Page: 1 800-231-8040 productionproducts.net your existing duct fitting software. This dramatically improves liner utilization using your duct software’s nesting capabilities. The CNC cut parts match the metal fittings perfectly with nice clean edges. There are 2 options for cutting machine liners with the Liner Pro II -- a high speed router or high pressure water jet. Traverse speed (between parts) up to 1500 IPM regardless of cut speed One tool (bit) change required for 2†liners only Light weight rigid aluminum gantry with high speed router Heavy duty / heavy wall welded single unit square tube framing PC based PPI - PC - CNC control system ADDITIONAL INFORMATION -

In-Situ Observations of Single Micro-Particle Impact Bonding

In-situ observations of single micro-particle impact bonding The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Hassani-Gangaraj, Mostafa et al. "In-situ observations of single micro-particle impact bonding." Scripta Materialia, 145 (March 2018): 9-13 © 2017 Acta Materialia Inc. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2017.09.042 Publisher Elsevier BV Version Author's final manuscript Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/123866 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ M. Hassani-Gangaraj, D. Veysset, K. A. Nelson, and C. A. Schuh, Scripta Materialia. 145 (2018) 9-13. In-situ Observations of Single Micro-particle Impact Bonding Mostafa Hassani-Gangaraj1, David Veysset2,3, Keith A. Nelson2,3, Christopher A. Schuh1* 1Department of Materials Science and Engineering, MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA. 2Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA. 3Department of Chemistry, MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA. *Correspondence to: [email protected] Received 12 July 2017, Revised 25 September 2017, Accepted 26 September 2017, Available online 12 October 2017 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2017.09.042 Abstract We study supersonic impact of individual metallic microparticles on metallic substrates, that is, the unit process of materials buildup in cold spray coatings/additive manufacturing. We resolve the moment of impact bonding through real-time observations of single particle impacts with micron-scale and nanosecond-level resolution. We offer the first in-situ observation of a material- dependent threshold velocity, above which the particle undergoes an impact-induced jet-like material ejection and adheres to the substrate. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,222,155 B1 Blackmon Et Al

USOO6222155B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,222,155 B1 Blackmon et al. (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 24, 2001 (54) CUTTING APPARATUS WITH THERMAL 5,043,554 8/1991 Kohsaka et al. AND NONTHERMAL CUTTERS, AND 5,208.440 5/1993 Conley. ASSOCATED METHODS 5,218,180 6/1993 Fujishima. 5,229.571 7/1993 Neiheisel. 5,262,612 11/1993 Momany et al.. (75) Inventors: Joseph B. Blackmon, Darlington, SC 5,350,897 9/1994 Chun. (US); James L. Segroves, Garland, TX 5,380,976 1/1995 Couch, Jr. et al.. (US) 5,481,083 1/1996 Smyth, Jr.. 5,560,843 10/1996 Koike et al.. (73) Assignee: The Esab Group, Inc., Florence, SC 5,635,086 6/1997 Warren, Jr. et al.. (US) 5,866,872 2/1999 Lu et al. B1 4,554,635 10/1995 Levine. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 OTHER PUBLICATIONS U.S.C. 154(b) by 4 days. ESAB Cutting Systems, Piecemaker 2, Technical Data Sheet, 11/99, 2 pp. (21) Appl. No.: 09/593,548 * cited by examiner (22) Filed: Jun. 14, 2000 Primary Examiner Mark Paschall (51) Int. Cl. ................................................... B23K 10/00 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Alston & Bird LLP (52) U.S. Cl. ................................ 219/121.39; 219/121.44; 219/121.48; 219/121.58; 219/121.59; 266/67; (57) ABSTRACT 266/65 A table has a pervious Support Surface and a gantry is (58) Field of Search ......................... 219/121.39, 121.44, mounted for movement across the Support Surface in a 219/121.58, 121.48, 121.59, 121.67; 266/65, longitudinal direction. -

Total Cost for All Labs

TOTAL COST FOR ALL LABS Lab Cost NDT Lab $ 172,440.00 Specialized Welding Room $ 27,915.98 Automation Lab $ 1,971,307.50 New GMAW Lab $ 204,026.00 Material Storage Area $ 88,000.00 New Cutting Grinding Area $ 35,868.00 Fabrication Lab Equipment $ 488,372.28 Supplies $ 23,072.67 Existing Labs $ 336,776.00 Total $ 3,347,778.43 BREAKDOWN OF COST BY LAB NDT Lab Equipment Quantity Price Total Workstation tables with 110 receptacles 9 $ 1,000.00 $ 9,000.00 Equipment storage cabinets 4 $ 1,760.00 $ 7,040.00 Ventilation downdraft system 1 $ 14,000.00 $ 14,000.00 Chemical fume hood 1 $ 27,000.00 $ 27,000.00 Digital X-ray machine 1 $ 72,000.00 $ 72,000.00 Film processor 1 $ 8,000.00 $ 8,000.00 Phased array UT units 2 $ 17,000.00 $ 34,000.00 Magnetic particle units with adjustable yokes 2 $ 700.00 $ 1,400.00 Total $ 172,440.00 Specialized Welding Room Equipment Quantity Price Total Workstation tables 2 $ 1,000.00 $ 2,000.00 Storage cabinets (GMI EX 843-1) 2 $ 1,028.00 $ 2,056.00 Bench top vises 2 $ 329.99 $ 659.98 Wall mounted ventilation units 2 $ 3,000.00 $ 6,000.00 Power supply (Miller Dynasty 200) 1 $ 3,200.00 $ 3,200.00 Purge tank/chamber (4-hole purge chamber) 1 $ 14,000.00 $ 14,000.00 Total $ 27,915.98 Pennsylvania College of Technology • Institutional Advancement • 570-320-8020 • [email protected] The Pennsylvania College of Technology Foundation, Inc. -

2016-2017 SAE Baja Design/Manufacturing Project

2016-2017 SAE Baja Design/Manufacturing Project Hani Alnakhly (MECET, Design Emphasis) Mohnannad Gazzaz (MECET, Design Emphasis) Azmi Awari (MECET, Design Emphasis) Turki Al-Rashid (MECET, Design Emphasis) Sultan Alshammari (MECET, Design Emphasis) Abraham Ittycheri (MECET, Electromechanical Emphasis) Introduction to SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) Baja Competition-2017 • Four day long competition (May 25th to 28th) • Hosted by Pittsburg State University • Multidepartment project (MECET, Automotive Technology) Created By Abraham Ittycheri Components of the Event • Inspection • Dynamic Event • Endurance Test • Design Finals Created By Abraham Ittycheri Problem Statement • Car that can function pass SAE inspection • Strategic car that perform well during the competition • Meet the budget requirement Material For The Tubing Material: ASTM A36 Steel Yield Strength: Min. 36,000 psi Tensile Strength: 58,000 – 80,000 psi The reason behind using this material? Created By Mohannad Gazzaz Frame Consideration for manufacturing phase: • SAE Guideline • Design compatibility Created By Mohannad Gazzaz Manufacture Tools CHOP SAW STEEL BURR BURR REMOVAL Created By Mohannad Gazzaz Manufacturing Tools BURR REMOVAL AND SCUFFING MILLING MACHINE Created By Mohannad Gazzaz Manufacturing Tools BENDING MACHINE WELDING MACHINE Created By Mohannad Gazzaz Manufacturing Tools TUPING COPING WATER JET Frame Length, Height, and Width Objective Outcome Maximum of 108 inches in length 91 inches Height is based on the driver 60 inches Maximum of 64 inches in width 59 inches Created By Mohannad Gazzaz Frame Height and Width Created By Mohannad Gazzaz Frame Length: Created By Mohannad Gazzaz SAE Baja Suspension • Overview • Definition Suspension is the term given to the system of shock absorbers and linkages that connects between a vehicle and its wheels.