Ethiopia Overview Print Page Close Window

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Red Terror NEVER AGAIN

Praise for books by Nobel Peace Prize finalist R. J. Rummel "26th in a Random House poll on the best nonfiction book of the 20th Century" Random House (Modern Library) “. the most important . in the history of international relations.” John Norton Moore Professor of Law and Director, Center for National Security Law, former Chairman of the Board of Directors of the U. S. Institute of Peace “. among the most exciting . in years.” Jim Powell “. most comprehensive . I have ever encountered . illuminating . .” Storm Russell “One more home run . .” Bruce Russett, Professor of International Relations “. has profoundly affected my political and social views.” Lurner B Williams “. truly brilliant . ought to be mandatory reading.” Robert F. Turner, Professor of Law, former President of U.S. Institute of Peace ". highly recommend . ." Cutting Edge “We all walk a little taller by climbing on the shoulders of Rummel’s work.” Irving Louis Horowitz, Professor Of Sociology. ". everyone in leadership should read and understand . ." DivinePrinciple.com “. .exciting . pushes aside all the theories, propaganda, and wishful thinking . .” www.alphane.com “. world's foremost authority on the phenomenon of ‘democide.’” American Opinion Publishing “. excellent . .” Brian Carnell “. bound to be become a standard work . .” James Lee Ray, Professor of Political Science “. major intellectual accomplishment . .will be cited far into the next century” Jack Vincent, Professor of Political Science.” “. most important . required reading . .” thewizardofuz (Amazon.com) “. valuable perspective . .” R.W. Rasband “ . offers a desperately needed perspective . .” Andrew Johnstone “. eloquent . very important . .” Doug Vaughn “. should be required reading . .shocking and sobering . .” Sugi Sorensen NEVER AGAIN Book 4 Red Terror NEVER AGAIN R.J. -

Ethiopia Briefing Packet

ETHIOPIA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET ETHIOPIA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ETHIOPIA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY 5 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 7 Health Infrastructure 7 Water Supply and sanitation 9 Health Status 10 FLAG 12 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 13 General overview 13 Climate and Weather 13 Geography 14 History 15 Demographics 21 Economy 22 Education 23 Culture 25 Poverty 26 SURVIVAL GUIDE 29 Etiquette 29 LANGUAGE 31 USEFUL PHRASES 32 SAFETY 35 CURRENCY 36 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 24 MAY, 2016 37 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 38 TIME IN ETHIOPIA 38 EMBASSY INFORMATION 39 WEBSITES 40 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ETHIOPIA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the 2016 ETHIOPIA Medical Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The final section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. -

Oromo Democracy): an Example of Classical African Civilization

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Major Studies and Reports Commission for Blacks 3-2012 Gadaa (Oromo Democracy): An Example of Classical African Civilization Asafa Jalata Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_blackmaj Recommended Citation Jalata, Asafa, "Gadaa (Oromo Democracy): An Example of Classical African Civilization" (2012). Major Studies and Reports. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_blackmaj/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Commission for Blacks at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Studies and Reports by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gadaa (Oromo Democracy): An Example of Classical African Civilization by Asafa Jalata, Ph.D. [email protected] Professor of Sociology, Global Studies, and Africana Studies The University of Tennessee, The Department of Sociology Knoxville, Tennessee Abstract The paper briefly introduces and explains the essence of indigenous Oromo democracy and its main characteristics that are relevant for the current condition of Africa in general and Oromo society in particular. It also illustrates how Oromo democracy had functioned as a socio-political institution by preventing oppression and exploitation and by promoting relative peace, security, sustainable development, and political sovereignty, and how the gadaa system organized Oromo society -

Oromo Indigenous Religion: Waaqeffannaa

Volume III, Issue IV, April 2016 IJRSI ISSN 2321 – 2705 Oromo Indigenous Religion: Waaqeffannaa Bedassa Gebissa Aga* *Lecturer of Human Rights at Civics and Ethical Studies Program, Department of Governance, College of Social Science, of Wollega University, Ethiopia Abstract: This paper discusses the African Traditional religion on earth. The Mande people of Sierra-Leone call him as with a particular reference to the Oromo Indigenous religion, Ngewo which means the eternal one who rules from above.3 Waaqeffannaa in Ethiopia. It aimed to explore status of Waaqeffannaa religion in interreligious interaction. It also Similar to these African nations, the Oromo believe in and intends to introduce the reader with Waaqeffannaa’s mythology, worship a supreme being called Waaqaa - the Creator of the ritual activities, and how it interrelates and shares with other universe. From Waaqaa, the Oromo indigenous concept of the African Traditional religions. Additionally it explains some Supreme Being Waaqeffanna evolved as a religion of the unique character of Waaqeffannaa and examines the impacts of entire Oromo nation before the introduction of the Abrahamic the ethnic based colonization and its blatant action to Oromo religions among the Oromo and a good number of them touched values in general and Waaqeffannaa in a particular. For converted mainly to Christianity and Islam.4 further it assess the impacts of ethnic based discrimination under different regimes of Ethiopia and the impact of Abrahamic Waaqeffannaa is the religion of the Oromo people. Given the religion has been discussed. hypothesis that Oromo culture is a part of the ancient Cushitic Key Words: Indigenous religion, Waaqa, Waaqeffannaa, and cultures that extended from what is today called Ethiopia Oromo through ancient Egypt over the past three thousand years, it can be posited that Waaqeffannaa predates the Abrahamic I. -

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration Andintegration

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration andIntegration DYLAN RILEY AND REBECCA JEAN EMIGH* ABSTRACT The effect ofItalian colonialismon migration to Italy differedaccording to the pre-colonialsocial structure, afactor previouslyneglected byimmigration theories. In Eritrea,pre- colonialChristianity, sharp class distinctions,and a strong state promotedinteraction between colonizers andcolonized. Eritrean nationalismemerged against Ethiopia; thus, nosharp breakbetween Eritreans andItalians emerged.Two outgrowths ofcolonialism, the Eritrean nationalmovement andreligious ties,facilitate immigration and integration. In contrast, in Somalia,there was nostrong state, few class differences, the dominantreligion was Islam, andnationalists opposed Italian rule.Consequently, Somali developed few institutionalties to colonialauthorities and few institutionsprovided resources to immigrants.Thus, Somaliimmigrants are few andare not well integratedinto Italian society. * Direct allcorrespondence to Rebecca Jean Emigh, Department ofSociology, 264 HainesHall, Box 951551,Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551;e-mail: [email protected]. ucla.edu.We would like to thank Caroline Brettell, RogerWaldinger, and Roy Pateman for their helpfulcomments. ChaseLangford made the map.A versionof this paperwas presentedat the Tenth International Conference ofEuropeanists,March 1996.Grants from the Center forGerman andEuropean Studies at the University ofCalifornia,Berkeley and the UCLA FacultySenate supported this research. ComparativeSociology, Volume 1,issue 2 -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

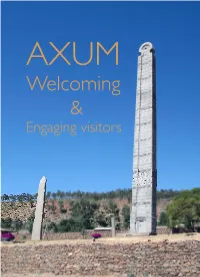

AXUM – Welcoming and Engaging Visitors – Design Report

Pedro Guedes (2010) AXUM – Welcoming and engaging visitors – Design report CONTENTS: Design report 1 Appendix – A 25 Further thoughts on Interpretation Centres Appendix – B 27 Axum signage and paving Presented to Tigray Government and tourism commission officials and stakeholders in Axum in November 2009. NATURE OF SUBMISSION: Design Research This Design report records a creative design approach together with the development of original ideas resulting in an integrated proposal for presenting Axum’s rich tangible and intangible heritage to visitors to this important World Heritage Town. This innovative proposal seeks to use local resources and skills to create a distinct and memorable experience for visitors to Axum. It relies on engaging members of the local community to manage and ‘own’ the various ‘attractions’ for visitors, hopefully keeping a substantial proportion of earnings from tourism in the local community. The proposal combines attitudes to Design with fresh approaches to curatorship that can be applied to other sites. In this study, propositions are tested in several schemes relating to the design of ‘Interpretation centres’ and ideas for exhibits that would bring them to life and engage visitors. ABSTRACT: Axum, in the highlands of Ethiopia was the centre of an important trading empire, controlling the Red Sea and channeling exotic African merchandise into markets of the East and West. In the fourth century (AD), it became one of the first states to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Axum became the major religious centre for the Ethiopian Coptic Church. Axum’s most spectacular archaeological remains are the large carved monoliths – stelae that are concentrated in the Stelae Park opposite the Cathedral precinct. -

Ethnicity and Nationality Among Ethiopians in Canada's Census Data: a Consideration of Overlapping and Divergent Identities

UC Merced UC Merced Previously Published Works Title Ethnicity and nationality among Ethiopians in Canada's census data: a consideration of overlapping and divergent identities. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3pt9v7fp Journal Comparative migration studies, 6(1) ISSN 2214-594X Author Thompson, Daniel K Publication Date 2018 DOI 10.1186/s40878-018-0075-5 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Thompson Comparative Migration Studies (2018) 6:6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0075-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Ethnicity and nationality among Ethiopians in Canada’s census data: a consideration of overlapping and divergent identities Daniel K. Thompson1,2 Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 1 Department of Anthropology, ‘ ’ Emory University, 1557 Dickey Drive, This article addresses the intersection of homeland politics and diaspora identities Atlanta, GA 30322, USA by assessing whether geopolitical changes in Ethiopia affect ethno-national identifications 2College of Social Sciences and among Ethiopian-origin populations living abroad. Officials in Ethiopia’slargestethnically- Humanities, Jigjiga University, Jigjiga, Ethiopia defined states recently began working to improve diaspora-homeland relations, historically characterised by ethnically-mobilized support for opposition and insurgency. The emergence of an ‘Ethiopian-Somali’ identity indicated in recent research, previously regarded as a contradiction in terms, is the most striking of a series of realignments -

Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen

Greenland Iceland Finland Norway Sweden Estonia Latvia Denmark Lithuania Northern Ireland Canada Ireland United Belarus Kingdom Netherlands Poland Germany Belgium Czechia Ukraine Slovakia Russia Austria Switzerland Hungary Moldova France Slovenia Kazakhstan Croatia Romania Mongolia Bosnia and HerzegovinaSerbia Montenegro Bulgaria MMC East AfricaKosovo and Yemen 4Mi Snapshot - JuneGeorgia 2020 Macedonia Uzbekistan Kyrgyzstan Italy Albania Armenia Azerbaijan United States Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen North Portugal Greece Turkmenistan Tajikistan Korea Spain Turkey South The ‘Eastern Route’ is the mixed migration route from East Africa to the Gulf (through Overall, 60% of the respondents were from Ethiopia’s Oromia Region (n=76, 62 men and Korea Japan Yemen) and is the largest mixed migration route out of East Africa. An estimated 138,213 14Cyprus women). OromiaSyria Region is a highly populated region which hosts Ethiopia’s capital city refugees and migrants arrived in Yemen in 2019, and at least 29,643 reportedly arrived Addis Ababa.Lebanon Oromos face persecution in Ethiopia, and partner reports show that Oromos Iraq Afghanistan China Moroccobetween January and April 2020Tunisia. Ethiopians made up around 92% of the arrivals into typically make up the largest proportion of Ethiopians travelingIran through Yemen, where they Jordan Yemen in 2019 and Somalis around 8%. are particularly subject to abuse. The highest number of Somali respondents come from Israel Banadir Region (n=18), which some of the highest numbers of internally displaced people Every year, tensAlgeria of thousands of Ethiopians and Somalis travel through harsh terrain in in Africa. The capital city of Mogadishu isKuwait located in Banadir Region and areas around it Libya Egypt Nepal Djibouti and Puntland, Somalia to reach departure areas along the coastline where they host many displaced people seeking safety and jobs. -

The Role of the Ethiopian Diaspora in Ethiopia

The Role of the Ethiopian Diaspora in Ethiopia Solomon Getahun Paper presented at Ethiopia Forum: Challenges and Prospects for Constitutional Democracy in Ethiopia International Center, Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan, March 22-24, 2019 Abstract: The Ethiopian diaspora is a post-1970s phenomenon. Ethiopian government sources has it that there are more than 3 million Ethiopians scattered throughout the world: From America to Australia, from Norway to South Africa. However, the majority of these Ethiopians reside in the US, the Arab Middle East, and Israel in that order. Currently, a little more than a quarter of a million Ethiopians live in the US. The Ethiopian diaspora in the US, like its compatriots in other parts of the world, is one of the most vocal critic of the government in Ethiopia. However, its views are as diverse as the ethnic and regional origins, manners of entry into the US, generation, and levels of education. However, the intent of this paper is not to discuss the migration history of Ethiopians but to explore some of the reasons that caused the political fallout between the various regimes in Ethiopia and the Diaspora- Ethiopians. In the meantime, the paper examines the potential and actual roles that the Ethiopian diaspora can play in Ethiopia. The Making of the Ethiopian Diaspora in the US: A Synopsis One can trace back the roots of the Ethiopian diaspora in the US to the establishment of diplomatic ties between the Government of Ethiopia and the US in 1903. In that year, the US government sent a delegation, the Skinner Mission, to Ethiopia.1 It was during this time that Menelik II, King of Kings of Ethiopia, in addition to signing trade deals with the US, expressed his interest in sending students to the United States.