The Long-Term Development Pattern and Arrangement of Various Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Summary

4 Executive Summary Sponsored by the City of Valparaiso Redevelopment Commission additional transportation and utilities infrastructure improvements will provide access to additional lands for office park development and Planning Department, this Corridor Plan was developed to are warranted. as well as a proposed multi-family housing development, before address landscape conservation and development-related issues connecting with the Eastport Centre Technology Park and beyond along a portion of State Route 49, extending from U.S. Highway The SR 49 thoroughfare will always remain a critical regional to the expanding Porter County Regional Airport. 30 northward to U.S. Highway 6, a distance of approximately six link between the Porter County Regional Airport and its adjacent miles. The width of the corridor study area generally extended industrial activity, and the Port of Indiana-Burns Harbor on the An ambitious plan, the development of Memorial Drive Extended from Silhavy Road / Calumet Road eastward to County Road 325, shore of Lake Michigan. In 2011, the SR 49 thoroughfare’s ensures a coherent pattern of contiguous development that encompassing an area of approximately ten square miles. level of service (LOS) rating was C. In anticipation of increased prevents sprawl and preserves open space and rural landscape vehicular traffic the SR 49 thoroughfare must improve its LOS. character. The proposed thoroughfare promotes connectivity and The principal objective of the SR 49 Corridor Plan is to provide The presence of a signaled intersection at CO Rd 500 and the access management to existing transportation corridors while planning guidance and physical design direction for urban complete lack of signalization at the interchange of SR 49 and providing synergies with adjacent complementary land uses. -

Purpose and Need

NORTHERN INDIANA PASSENGER RAIL CORRIDOR PURPOSE AND NEED Chicago-Fort Wayne-Lima Corridor Prepared for the City of Fort Wayne, IN November 2017 Northern Indiana Passenger Rail Corridor Purpose and Need CONTENTS 1 Introduction and Background .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Description ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Current Project Phase/NEPA ....................................................................................... 2 1.3 Passenger Rail Service Background ............................................................................ 2 1.4 Prior Planning Studies ................................................................................................. 2 1.4.1 Midwest Regional Rail Initiative ............................................................................. 2 1.4.2 Ohio Hub System ................................................................................................... 3 1.4.3 NIPRA Feasibility Study ......................................................................................... 3 2 Purpose and Need .............................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Project Purpose ........................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Project Need ............................................................................................................... -

Transportation to & from Campus

Getting to The quick and easy guide for getting to and from campus Valparaiso University is approximately an hour from downtown Chicago, so getting to and from campus can be easy! Follow this guide to help understand the ins and outs of getting to the region’s major transportation hubs and the vibrant surrounding area of Porter County. MIDWAY GETTING INTERNATIONAL THERE AIRPORT • One-hour drive by car Distance from Campus: 57 miles • ChicaGO Dash Bus - Downtown Airport Code: MDW Valparaiso > Orange Line Train Airlines Serviced: Allegiant Air, • South Shore Train to Millenium Delta, Porter, Southwest Stop > Orange Line to Midway Airlines, Volaris SOUTH SHORE GETTING TRAIN THERE Distance from Campus: • 20-minute drive by car 14 miles • South Shore Connect Express Route: Downtown Chicago Millennium Station to South (Valpo V-Line) Bus stop located Bend, IN Airport on the north side of campus at Local Stop: Dune Park — University & LaPorte Ave. Chesterton, IN O’HARE GETTING INTERNATIONAL THERE AIRPORT • 1.5-hour drive by car Distance from Campus: 74 miles • ChicaGO Dash Bus — Downtown Airport Code: ORD Valparaiso > Blue Line Train Airlines Serviced: Most major • South Shore Line Train to Millenium international airline carriers Stop > Blue Line to O’Hare VALPO V-LINE TRANSIT SYSTEM The V-Line Transit Bus system is FREE for Valparaiso University students with valid student ID and has four routes with stops at locations including the South Shore Line, Valparaiso University, major local shopping centers, and downtown Valparaiso.. -

Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority Return on Investment Analysis

Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority Return on Investment Analysis November, 2012 RDA Return on Investment Analysis Table of Contents Introduction and Overview ...................................................................... 3 Methodology Description .......................................................................... 4 Project Leveraging ....................................................................................... 5 Shoreline Development .............................................................................. 6 Gary Chicago International Airport .................................................... 12 Surface Transportation ........................................................................... 17 Fiscal Impact ............................................................................................... 21 Total Economic Impact and ROI .......................................................... 22 2 RDA Return on Investment Analysis Overview and Summary The RDA was created in 2005 by the Indiana General Assembly to invest in the infrastructure and assets of Northwest Indiana [IC 36-7.5], and in so do- ing transform the economy and raise the quality of life for the region. The enabling statute listed four areas: 1) Assist in the development of the Gary Chicago International Airport. 2) Assist in the development of the Lake Michigan Shoreline. 3) Assist in the development of an integrated region-wide surface trans- portation system – encompassing both commuter rail and bus. 4) Assist in the development -

Chicago Downtown Chicago Connections

Stone Scott Regional Transportation 1 2 3 4 5Sheridan 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dr 270 ter ss C en 619 421 Edens Plaza 213 Division Division ne 272 Lake Authority i ood s 422 Sk 422 u D 423 LaSalle B w 423 Clark/Division e Forest y okie Rd Central 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie 422 The Regional Transportation Authority r P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware 620 421 0 E/W eehan Preserve Wilmette C Union Pacific/North Line 3rd 143 l Forest Baha’i Temple F e La Elm ollw Green Bay a D vice 4th v Green Glenview Glenview to Waukegan, Kenosha and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T i lo 210 626 Evanston Elm n (RTA) provides financial oversight, Preserve bard Linden nonstop between Michigan/Delaware e Dewes b 421 146 s Wilmette 221 Dear Milw Foster and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) funding, and regional transit planning R Glenview Rd 94 Hi 422 221 i i-State 270 Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Rand v r Emerson Chicago Downtown Central auk T 70 e Oakton National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Map Legend Hill 147 r Cook Co 213 and Marine/Foster (5200N) for the three public transit operations Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central Courts k Central 213 93 Maple College 201 Sheridan nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Holy 422 S 148 Old Orchard Gross 206 C Northwestern Univ Hobbie and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) Dee Family yman 270 Point Central St/ CTA Trains Hooker Wendell 22 70 36 Bellevue L in Northeastern Illinois: The Chicago olf Cr Chicago A Harrison 54A 201 Evanston 206 A 8 A W Sheridan Medical 272 egan osby Maple th Central Ser 423 201 k Illinois Center 412 GOLF Westfield Noyes Blue Line Haines Transit Authority (CTA), Metra and Antioch Golf Glen Holocaust 37 208 au 234 D Golf Old Orchard Benson Between O’Hare Airport, Downtown Newberry Oak W Museum Nor to Golf Golf Golf Simpson EVANSTON Oak Research Sherman & Forest Park Oak Pace Suburban bus. -

Valparaiso Redevelopment Commission

TRANSPORTATION DEPARTMENT 166 Lincolnway Valparaiso, IN 46383 Phone: (219) 462-1161 Fax: (219) 464-4273 www.valpo.us September 12, 2020 Dear Vendor, The Valparaiso Planning Department is requesting proposals from contractors for snow removal and ice treatment for the Village Station Chicago Dash parking lot (located 260 Brown Street) and the City’s nine (9) V-Line bus shelters. In addition to those properties, the City is also seeking snow removal at 406 Don Hovey Drive where the City’s fleet of public transportation buses are stored and the new ChicaGo Dash parking lot at 260 Brown Street. Bid #1: ChicaGo Dash Station parking lot (approximate address: 260 Brown Street) This area to be plowed is about 1.5 acres, which includes the new ChicaGo Dash parking lot (including drive lane/alley), the sidewalks on the North side of Brown Street in front parking lot, up to the CSX Railroad Tracks and around the bike lockers. A map defining the area is attached to the request for proposals. There are two entry drives into the parking lot from Brown Street. Please show separate prices for the following items (see attached Proposal Form): 1. removal of snow in the ChicaGO Dash Parking Lot as designated in Exhibit D a) Estimated time to complete job after a 2” snow b) Estimated time to complete job after a 2” snow 2. flat monthly fee (November 2020 through March 2021) for the maintenance of the Transit Campus for snow and ice removal and melting. Removal of the snow is to be done when more than 2” of snow has fallen. -

Membership Directory

2018-2019 Membership Directory 2018 -2019 Membership Directory & Community Resource Guide Find it ValpoChamber.orgvalpochamber.org SinceSince 1990, 1990, innovative innovative individualsindividualsSince and 199 and 0 , innovative organizationsorganizationsindividuals around around and the the globeglobe ohave rhaveganiz trusted trustedations a round the Hartmanglobe Global’s have trusted Hartman Global’s world-classHARTMAN expertise. GLOBAL’s world-class expertise. world-class expertise. PATENTS | TRADEMARKS | COPYRIGHTS | LICENSING PATENTSPATENTS | TRADEMARKS | TRADEMARK S| COPYRIGHTS| COPYRIGHTS | |LICENSING LICENSING HartmanGlobal-IP.com | 219.462.4999 2621HartmanGlobal-IP.com ChicagoHartma nStreet,Global-I SuiteP.com A, | Valparaiso 219.462.4999| 219.462.4999 INTELLECTUAL26212621 Chicago Chica PROPERTY gStreet,o Street, Suite S EXCLUSIVELY.uite A, A, Valparaiso Valparaiso INTELLECTUAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROPERTY EXCLUSIVELY. EXCLUSIVELY. Rice & Rice Attorneys... A Cornerstone in Our Community for 45 years Call Now! (800) 303-RICE Free Consultation • Medicaid Planning to Avoid Nursing Home Spend-Down • Elder Law, Long-Term Care Planning and In-Home Healthcare Planning • Living Trusts, Probate Avoidance, Business and Farmland Succession Planning Cliff Rice Elder Law Attorney ELD E R L A W AND E S T A T E P L ANNING SERVING I NDIANA , ILLINOIS AND MICHIGAN WITH O FFICES IN VALPAR AISO, G R ANGER A ND L AFAYET TE Rice & Rice Attorneys 100 L incolnway, S uite 1 , Valparaiso, In 4 6383 RiceandRice.com Advertising Material (800) 303-RICE n 219.462.1105 n ValpoChamber.org 3 Page 4 Welcome & Chamber Staff Welcome Page 5 to the 2018-19 Membership Directory. Our Chamber BY THE NUMBERS On behalf of the Valpo Chamber, I am pleased to present the 2018-19 Membership Directory. -

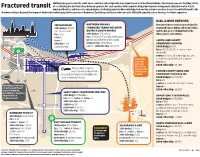

Fractured Transit at Coordinating Bus and Train Times Between Agencies, but Each Operates with a Separate Budget and Separate Management

Multiple bus agencies and the South Shore commuter railroad provide mass transit services in Northwest Indiana. There have been some fledgling efforts Fractured transit at coordinating bus and train times between agencies, but each operates with a separate budget and separate management. Many bus routes stop at municipal borders, and there is no system in place for buying transfers when switching from one bus system to another. A report recently delivered to the Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority found merging the bus systems of Hammond, East Chicago and Gary could save up to $500,000 annually and set the stage for future expansion. DIAL-A-RIDE SERVICES CHICAGO DASH NORTHERN INDIANA Demand-response services operate just like 2009 budget: $111,193 COMMUTER TRANSPORTATION you would expect. Riders call ahead of time, (Oct. ’08 to current) DISTRICT (SOUTH SHORE) and the bus goes to them instead of the fare: $7.50 2008 budget: $38.2 million rider going to a bus station. routes: 1 fare: $3.80 to $7.45 one-way (Hammond to buses: 3 Millennium/South Bend to Millennium) SOUTH LAKE COUNTY ridership: 8,364 trains per day: 43 (weekday) COMMUNITY SERVICES (January to July) cars: 82 2008 ridership: 4.2 million 2008 budget: N.A. fare: $5.25 ($3.25 for seniors and * disabled) routes: Covers all townships in Lake V-Line service County except North and Calumet to the Dune buses: 8 Park South 2008 ridership: 13,500 Shore Station UPS pays PACE to operate operates solely seven daily nonstop buses from on Fridays and PORTER COUNTY AGING AND Gary and East Chicago to the Hodgkins UPS weekends. -

System Includes 145 Stations, of Which 102 Touhy Northwest290 Hwy 290 290 157 Mannheim Ri Cald 22 Dee

Stone Amtrak provides rail service 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scott 13 14 Regional Transportation Sheridan LaSalle r Dr 270 from Chicago’s Union Station s C ente 421 Authority es 619 272 Edens Plaza Lake 213 Division Division sin ood u D 423 422 422 B w Antioch Clark/Division to cities throughout Illinois y Central 423 e Forest 151 a WILMETTE The Regional Transportation amie ville s n r 422 w P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W 0 E/W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware to Preserve 620 C 421Union Pacific/North Line3rd eeha l Forest Wilmette e La Baha’i Temple 143 F oll and United States. Many a D Green Bay Elm 4th v Green Glenview and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T Glenview i Authority (RTA) provides lo Elm n r 210 Preserve 626 to Waukegan, Kenosha bard Linden Evanston e nonstop between Michigan/Delaware vice Dewes b 421 of these routes, combined with s Dea Mil Wilmette Foster 146 221 Hi and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) financial oversight, funding, and R Glenview Rd 94 w 422 i i-State Chicago Downtown 221 Rand v r 270 au Emerson Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Oakton T Central Thruway buses, e National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Hill 70 147 regional transit planning for the r k Cook Co and Marine/Foster (5200N) Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central 213 Courts k Central 213 93 Sheridan Maple nonstop between Delaware/Michigan College S connect 35 Illinois cities. Presence 422 Gross 206 201 C Hobbie 148 Dee three public transit operations in yman 270 Huber Old Orchard Point Central St/ Northwestern Univ Hooker Bellevue and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) -

Fort Wayne, Citilink

2009 ANNUAL REPORT INDIANA PUBLIC TRANSIT STATE OF INDIANA Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr., Governor Michael Cline, Commissioner, Indiana Department of Transportation August 2010 Indiana Department of Transportation Office of Transit 100 North Senate, Room N955 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 (317) 232-1482 This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the Indiana Department of Transportation, Office of Transit. The preparation of this publication has been financed in part through grants from the United States Department of Transportation, under the provisions of the Federal Transit Act. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Manufacturers’ names appear herein because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. 2009 PUBLIC TRANSIT SYSTEMS IN INDIANA TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Ridership by System ................................................................................................ 2 Total Vehicle Miles by System ................................................................................ 3 Transit System Operating Expenditures by Category – 2009................................. 4 Transit System Operating Revenues -

East Chicago Transit)

Title VI Program Recertification Document Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Section 601 Specific to Federal Transit Administration Programs March 16, 2017 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission 6100 Southport Road Portage, Indiana 46368 Phone (219) 763.6060 Fax (219) 762.1653 e-mail: [email protected] 2017 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission Title VI Program Certification Document Table of Contents NIRPC’S RESOLUTION ADOPTING TITLE VI PLAN IDENTIFICATION OF DESIGNATED RECIPIENT, DIRECT GRANTEE, AND SUBRECIPIENTS ............................................................................................................ 1 PART I. NIRPC GENERAL REPORTING REQUIREMENTS ................................ 3 1. REQUIREMENT TO PROVIDE AN ANNUAL TITLE VI CERTIFICATION AND ASSURANCES ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. REQUIREMENT TO DEVELOP TITLE VI COMPLAINT PROCEDURES .......................... 3 3. REQUIREMENT TO RECORD TITLE VI INVESTIGATIONS, COMPLAINTS, & LAWSUITS ........................................................................................................................... 3 4. REQUIREMENT TO PROVIDE MEANINGFUL ACCESS TO LIMITED ENGLISH PROFICIENCY (LEP) PERSONS........................................................................................... 3 5. REQUIREMENT TO NOTIFY BENEFICIARIES OF PROTECTION UNDER TITLE VI ....... 3 6. SUMMARY OF PUBLIC OUTREACH AND INVOLVEMENT ACTIVITIES ........................ -

Moving Public Transportation Into the Future

V-Line Route Study DRAFT FINAL REPORT Prepared for the City of Valparaiso (V-Line) October 21, 2014 3131 South Dixie Hwy. Suite 545 Dayton, OH 45439 937.299.5007 www.rlsandassoc.com Moving Public Transportation Into the Future Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Approach ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Public Input .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Public and Focus Group Meeting Input Summary......................................................................................................... 2 Stakeholder Interview Summaries ...................................................................................................................................... 8 City of Valparaiso ................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Covington Square Apartments ......................................................................................................................................... 9 HealthLinc Community Health Center .........................................................................................................................