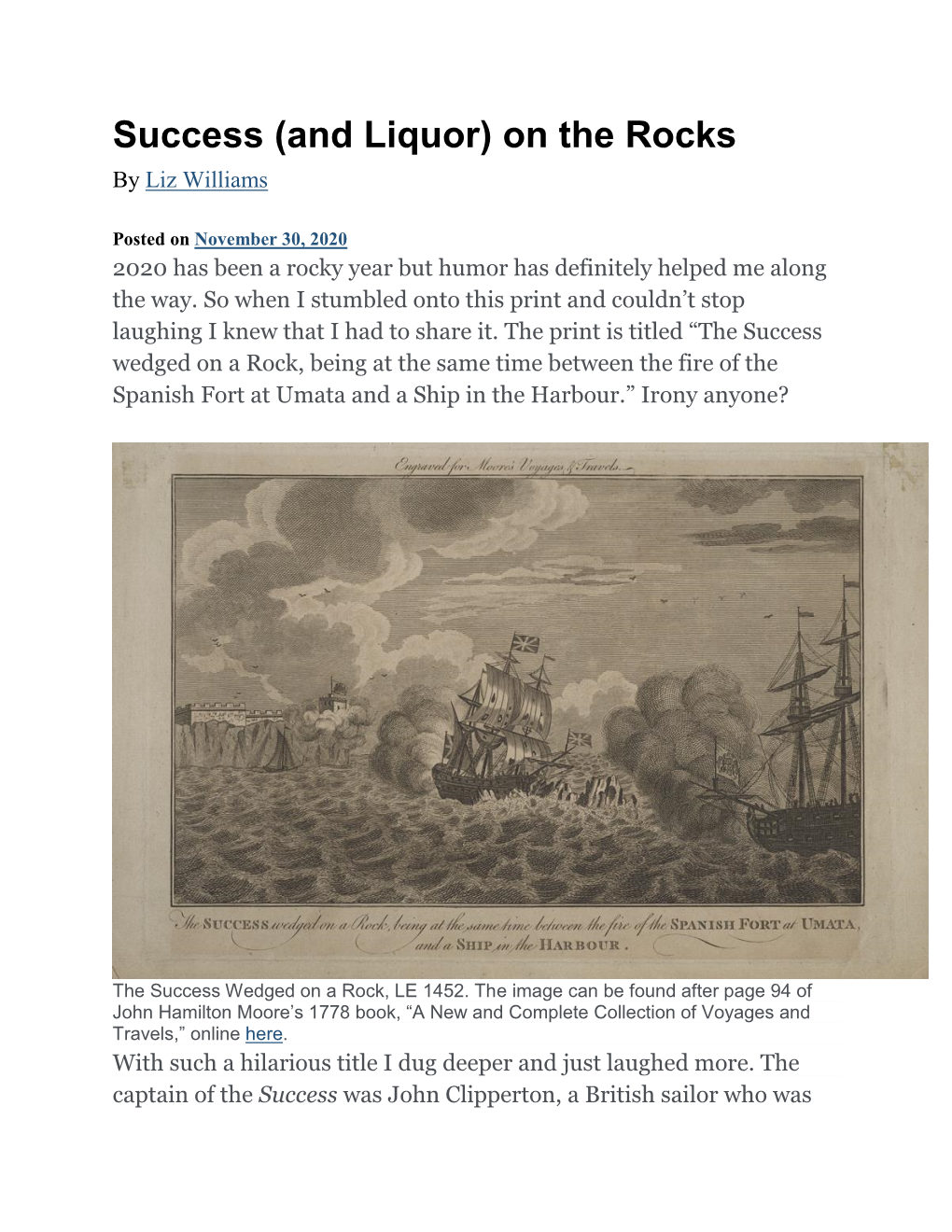

And Liquor) on the Rocks by Liz Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN DEEP WATER for Filing

IN DEEP WATER: THE OCEANIC IN THE BRITISH IMAGINARY, 1666-1805 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colin Dewey May 2011 © 2011 Colin Dewey IN DEEP WATER: THE OCEANIC IN THE BRITISH IMAGINARY, 1666-1805 Colin Dewey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This study argues that the ocean has determined the constitution of British identity – both the collective identity of an imperial nation and the private identity of individual imagination. Romantic-era literary works, maritime and seascape paintings, engravings and popular texts reveal a problematic national and individual engagement with the sea. Historians have long understood the importance of the sea to the development of the British empire, yet literary critics have been slow to take up the study of oceanic discourse, especially in relation to the Romantic period. Scholars have historicized “Nature” in literature and visual art as the product of an aesthetic ideology of landscape and terrestrial phenomena; my intervention is to consider ocean-space and the sea voyage as topoi that actively disrupt a corresponding aesthetic of the sea, rendering instead an ideologically unstable oceanic imaginary. More than the “other” or opposite of land, in this reading the sea becomes an antagonist of Nature. When Romantic poets looked to the ocean, the tracks of countless voyages had already inscribed an historic national space of commerce, power and violence. However necessary, the threat presented by a population of seafarers whose loyalty was historically ambiguous mapped onto both the material and moral landscape of Britain. -

Politics of Affect in Coleridge's the Rime of the Ancient Mariner

EJ-SOCIAL, European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN: 2736-5522 Politics of Affect in Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Dipak Raj Joshi continually acted upon”, and that “the events having no Abstract — This paper analyzes The Rime of the Ancient necessary connection” [1, p. 67]. Coleridge himself Mariner in terms of Coleridge’s imaginative plea for a commented The Rime having “the moral sentiment too modification of consciousness about racial slavery prevalent in apparent ... in a work of such pure imagination” [2, p. 105]. the then British society. What lends muscle to the plea is the use of gothic supernaturalism, which helps bring about a Southey called the poem “a Dutch attempt at German transformation in the Mariner. The gothic-actuated sublimity”, but Charles Lamb praised its magical power to transformation, this paper claims, derives from Coleridge’s own hold the reader’s attention, “we are dragged ... along like Tom ambiguous attitude to English imperialism—an ambivalence Piper’s magic whistle” [2, p. 107]. The poem is sensational in which results into systematic portrayal of the violator as the gothic mode. rightful beneficiary of the reader’s sympathy. The paper The Rime has also been reviewed from the perspective of concludes that the poem’s turn to the affect of moral sentimentalism intends to make the reader of Coleridge’s time slavery and abolitionism. White reads the poem as acquiesce in accepting colonial guilt as the spiritual politics of Coleridge’s sense of collective horror created by slavery. quietism, thereby averting the possibility of a violent reaction White finds the Mariner’s guilt reflected in the poem due to both from the hapless victims and some conscientious the new sensibility in the process of development and victimizers. -

En Patagonie

Bruce Chatwin / En Patagonie Tout voyageur est, d’abord, un rêveur. À partir d’un nom, d’une image, d’une lecture, il imagine une ville, un pays et n’a plus de cesse qu’il n’ait été vérifier, sur place, si la réalité cor- respond à son rêve. Bien sûr, la déception se trouve souvent au rendez-vous ; mais, parfois, non. Et, alors, tout peut arriver ; par exemple : un grand livre. Deux phénomènes de cet ordre sont à l’origine du départ de Bruce Chatwin pour la Patagonie, qui n’est pas précisément la destination la plus fréquemment choisie par les touristes. D’abord, « un fragment de peau… pas bien grand mais d’un cuir épais et couvert de touffes de poils roux (qu’)une punaise rouillée fixait à une carte postale. — Qu’est-ce que c’est, maman ? — Un morceau de brontosaure. » Non, il s’agissait d’une relique de mylodon, un paresseux géant. Encore fallait-il entreprendre l’équipée en question pour l’apprendre. Seconde incitation au voyage, vingt-cinq ans plus tard : une visite à Eileen Gray, le fameux « designer » comme on dit en français. Âgée de quatre-vingt-treize ans, elle ne voyait au- cune raison de ne pas travailler quatorze heures par jour. Cela ne lui laissait guère le loisir de voyager. « Elle habitait rue Bonaparte (à Paris). Dans son salon était accrochée une carte de la Patagonie, qu’elle avait coloriée à la gouache. — J’ai toujours rêvé d’y aller, dis-je. — Moi aussi, répondit-elle. Allez-y pour moi ! J’y allai… la carte d’Eileen Gray décore mon apparte- ment. -

Visiting the Rime: a Case Study of Adaptation As Process and Product with the Rime of the Ancient Mariner Sally Ferguson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 [Re]Visiting the Rime: A Case Study of Adaptation as Process and Product with The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Sally Ferguson University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ferguson, Sally, "[Re]Visiting the Rime: A Case Study of Adaptation as Process and Product with The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1593. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1593 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. [Re]Visiting the Rime: A Case Study of Adaptation as Process and Product with The Rime of the Ancient Mariner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Sally Ferguson Ouachita Baptist University Bachelor of Arts in English, 2014 May 2016 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. X Dr. Lissette Szwydky Thesis Director X X Dr. Sean Dempsey Dr. William Quinn Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This thesis combines adaptation theory with ecology to examine Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) and its adaptations; it argues further combinations of adaptation with evolutionary theory and ecological ideas could allow for a better interpretation of many texts. -

The Rhetorical Pirate Captain George Shelvocke

Travel Text Paper Shelvocke: The Rhetorical Pirate Captain George Shelvocke may be the only man in seafaring history to make people feel sorry for an accused pirate, looter and murderer. Although he may also have been the courageous, hard-nosed and morally upright leader of arguably the toughest and most challenging voyage in naval history. These two descriptions, stated in more extreme terms for the purposes of establishing the spectrum of thought on Shelvocke, also highlight the central issue addressed by Shelvocke’s travel text, or more specifically, by its dubious author. Authored by Shelvocke upon his long-awaited return to England, A Voyage Round the World by the Way of the Great South Sea provides readers with a firsthand account of the three and a half year voyage circumnavigating the globe with the primary purpose of looting treasure from Spanish ships along the West coast of South America. The sailors of this voyage started in England, and then ventured across the Atlantic to the East coast of South America. From there, the majority of the three years was spent sailing around South America and attempting to uphold the mission funded by the Gentlemen’s Adventurers Association along the Western coast. Once Shelvocke left California, the voyage was fairly uneventful. After crossing the Pacific and stopping on some islands by China, the crew proceeded onto the Indian Ocean, went around Africa and finally back to England. But the voyage was anything but a simple, pseudo-military operation. As Kenneth Poolman states, “The voyage of the Speedwell, high seas privateer, would encompass greed, envy, 1 tyranny, class hatred, and a crude socialism. -

History 305W/405: the Maritime Atlantic World in the Age of Sail, 1450-1850

History 305W/405: The Maritime Atlantic World in the Age of Sail, 1450-1850 Professor Michael Jarvis [email protected] Mondays 2:00-4:40 pm Office: Rush Rhees 455 Rush Rhees 362 Phone: 275-4558 Office Hours: Wed. 2:00-4:00 or by appt. Scope of Course: The study of European expansion into Africa and the Americas between the ages of Discovery and Revolution has taken many forms. Some historians have pursued their investigations topically (slavery, migration, economic development, gender, class formation, etc.) while others have focused on particular colonies or regions, often with nationalistic, political or cultural motivations. Indeed, considerably more attention has been devoted to those colonies and regions that became the United States than elsewhere, due primarily to the fact that this country has produced so many historians. This course breaks with past tradition by shifting the focus of inquiry to the Atlantic Ocean itself, as the geographic center of an expanding European world. Rather than treat the ocean as peripheral while studying the settlement of the Atlantic coast, we will be primarily concerned with activities that took place upon its watery face, delving into the lives of the thousands of mariners who were catalysts in identity formation, migration, and economic development. Adopting a transnational and cross-culturally comparative and connective approach, we will focus particularly on three topics: migration (forced and free), maritime activities (seafaring, shipping, and fishing), and commerce (port cities and merchant communities), admittedly with a bias toward an expanding British Empire in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the end of this course, you will hopefully appreciate the centrality of the sea and maritime enterprises to the histories of Africa, Europe, and the Americas. -

How Slaves Used Northern Seaports' Maritime Industry to Escape And

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Faculty Research & Creative Activity History May 2008 Ports of Slavery, Ports of Freedom: How Slaves Used Northern Seaports’ Maritime Industry To Escape and Create Trans-Atlantic Identities, 1713-1783 Charles Foy Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/history_fac Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Foy, Charles, "Ports of Slavery, Ports of Freedom: How Slaves Used Northern Seaports’ Maritime Industry To Escape and Create Trans-Atlantic Identities, 1713-1783" (2008). Faculty Research & Creative Activity. 7. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/history_fac/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research & Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Charles R. Foy 2008 All rights reserved PORTS OF SLAVERY, PORTS OF FREEDOM: HOW SLAVES USED NORTHERN SEAPORTS’ MARITIME INDUSTRY TO ESCAPE AND CREATE TRANS-ATLANTIC IDENTITIES, 1713-1783 By Charles R. Foy A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Dr. Jan Ellen Lewis and approved by ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION PORTS OF SLAVERY, PORTS OF FREEDOM: HOW SLAVES USED NORTHERN SEAPORTS’ MARITIME INDUSTRY TO ESCAPE AND CREATE TRANS-ATLANTIC IDENTIES, 1713-1783 By Charles R. Foy This dissertAtion exAmines and reconstructs the lives of fugitive slAves who used the mAritime industries in New York, PhilAdelphiA and Newport to achieve freedom. -

Pacific Voyages

PAcific voyAges Peter Harrington london Peter Harrington 1 We are exhibiting at these fairs: 12 –14 July 2019 melbourne Melbourne Rare Book Fair Wilson Hall, University of Melbourne www.rarebookfair.com 7–8 September brooklyn Brooklyn Expo Center 72 Noble St, Brooklyn, NY 11222 www.brooklynbookfair.com 3–6 October frieze masters Regent’s Park, London www.frieze.com/fairs/frieze-masters 5–6 October los angeles Rare Books LAX Proud Bird 11022 Aviation Blvd Los Angeles, CA https://rarebooksla.com 12–13 October seattle Seattle Antiquarian Book Fair 299 Mercer St, Seattle, WA www.seattlebookfair.com 2–3 November chelsea (aba) Chelsea Old Town Hall King’s Road, London sw3 5ee www.chelseabookfair.com 15–17 November boston Hynes Convention Center 900 Boylston St, Boston, MA 02115 http://bostonbookfair.com 22–24 November hong kong China in Print Hong Kong Maritime Museum Central Pier No. 8 www.chinainprint.com VAT no. gb 701 5578 50 Peter Harrington Limited. Registered office: WSM Services Limited, Connect House, 133–137 Alexandra Road, Wimbledon, London sw19 7jy. Registered in England and Wales No: 3609982 Cover illustration from Louis Choris, Vues et paysages des régions équinoxiales, item 67. Design: Nigel Bents. Photography: Ruth Segarra. Peter Harrington 1969 london 2019 catalogue 154 PACIFIC VOYAGES mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 dover street 100 FulHam road london w1s 4FF london sw3 6Hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 20 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 www.peterharrington.co.uk usa 011 44 20 7591 0220 PACIFIC VOYAGES Earlier this year we took a trip to the South Maui home of Cook’s last voyage (1784), inscribed from Cook’s ex- of the legendary book dealer Louis (Lou) Weinstein, for- ecutors to Captain William Christopher, a distinguished merly of Heritage Book Shop Inc. -

Wikipedia, Arts History Society Biography Mathematics Technology the Free Encyclopedia That Anyone Can Edit

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Main Page Talk Read View source View history Welcome to Wikipedia, Arts History Society Biography Mathematics Technology the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit. Main page Geography Science All portals 5,940,072 articles in English Contents Featured content Current events From today's featured article In the news Random article Donate to Wikipedia An earthquake strikes Wikipedia store Simon Hatley (1685 – after 1723) was an English sailor involved in two hazardous privateering voyages to the South Maluku, Indonesia, killing at Interaction Pacific Ocean. With his ship beset by storms south of Cape least 30 people. Help About Wikipedia Horn, Hatley shot an albatross, an incident immortalised by During a prolonged period Community portal Samuel Taylor Coleridge in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner of haze (pictured) over Haze over Jam Gadang in Indonesia Recent changes Southeast Asia, more than Contact page (illustrated). Hatley went to sea in 1708 under Captain Woodes Rogers, but was captured by the Spanish on the coast of Ecuador and 800,000 people endure respiratory diseases. Tools was tortured by the Inquisition. Hatley's second voyage, under George Shelvocke An earthquake in Kashmir kills 38 people and injures more What links here Related changes , was the source of the albatross incident, recorded in Shelvocke's journal for 1 than 700 others. Upload file October 1719, and also ended with his capture by the Spanish, who held him as a Astronomers announce that 2I/Borisov is the first verified Special pages Permanent link pirate for looting a Portuguese ship. -

The Sovereignty of Islands : a Contemporary Methodology for The

TITLE: THE SOVEREIGNTY OF ISLANDS: A CONTEMPORARY METHODOLOGY FOR THE DETERMINATION OF RIGHTS OVER NATURAL MARITIME RESOURCES NAME: Lieutenant Dominic Henley KATTER, RANR BA(Qld), LLB(Qld), LLM(Qld), MPhil(Cantab) MCIArb, MIAMA, ANZIIF(Mem), AIMM, FTIA Barrister at Law (Qld and the High Court of Australia) Barrister and Solicitor (Vic and NZ) Legal Practitioner (NSW, ACT and NT) Former Wakefield Scholar, Law Faculty, University of Cambridge Fellow of the Cambridge Commonwealth Trust SCHOOL/FACULTY: Law A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science at the Queensland University of Technology SUPERVISOR: ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR PHILIP TAHMINDJIS ASSOCIATE SUPERVISOR: MS FRANCES HANNAH DATE SUBMITTED FOR EXTERNAL EXAMINATION: 19 May 2003 (further submission 24 November) STUDENT NUMBER: 02279754 COURSE: DOCTOR OF JURIDICAL SCIENCE – LW 50 Please do not copy this document without permission. KEYWORDS Sovereignty – Islands – maritime resources – Falkland Islands – customary international law – maritime zones – delimitation – law of the sea – UNCLOS – boundaries – resources ABSTRACT Once it was said that the law followed the flag. Now, international law is everywhere. Its influence increases.1 Sovereignty is no longer an intra-national concept within International Law. It now involves a greater consideration of issues concerning the global community. This thesis develops a practical methodology for the determination of sovereignty over maritime natural resources. Customary international law regarding the use of resources within the maritime zones of islands on the high seas is rapidly developing. Traditional tests, such as the discovery and occupation of islands, are no longer the primary focus of the determination of sovereignty. The methodology expressed in this thesis is an application and adaptation of the current state of the international laws regarding islands within the high seas. -

Privateers and Privateering

^lOSANCElfj^. £^OKALIFOfttj, .^OFCALIFO/?^ >r & <TJ1J3NV-SQV^ ^AINfHWV ^l-UBRARY-Qc <$UIBRARY0^ ,\V\E-UNIVERS/a vvlOSANCElfj> %HI1V3-J0^ ^fOJIlVOJO^ "%3A!M-3t^ ^OKALIF(%, ^E-UNIVER5//v. ^lOSANCElfj^ e ^AavHan-^ ^fil33NV-S01^ "^AINIHtW ?% ^ios- ^SUIBRARY^ ^•HBRARYQc g ^^ DO ^otainmw^ ^WMITCHO^ ?% v^lOSANCELfj^ ^OFCALIFO/?^ O INA-3WV ^Aavaan-i^ ^Aavaan-3^ \V\EUNIVERto v^lOSANCElfx* ^OJIIVDJO^ <TJ13QNVS0^ %a3AIN03\W' \lifOM^ v^lOSANCElfj^ tW 0= ^ *^ ^ r*\ rllWi R% v^l0S-ANGElfj> S^OFCALIFO% ^OFC * ~r o I l n ^ J? )nvso^ %a3AiNiHt\v y0AavaaiH^ ^Aavaam^ ^ttlBRARYQr ^EUNIVERS/a ^vlOSANCElfx> -< JO^ ^/OJIIVOJO^ <TJ130NV-S01^ "^/WHAINfl-aiW* tAUFO/?^ ^OF-CALIF0% AttE-UNIVERty) vvlOSANCElfjv y0AHvaaiH^ <&to-sov^ %HAINfl-]tf^ osWSMCEl% ^LIBRARYQ^ <SSUIBRARY0/ j^" ^* O _1M_ o )NVS01^ %a]AINrt-3V\V ^lOS-ANGElft* ^OKAIIFO%, ^0F-CAIIF(% %. &-n | O-n %f3AiNfl-3t\v ^AHvaani^ ^Aavaan# <&12DNV-5 [^ ^UIBRARYQ^ AWEUNIVER5-/A ^clOSANCELfj^. ^UIBRAI ^C *3 ^Til3DNVS0# %a3AII«V CAUFO/?^ ^OFCAllFOfy^ ^WEUNIVERI/a ^lOSANCElfj^ O ^f -fc». «-* PRIVATEERS AND PRIVATEERING PRIVATEERS AND PRIVATEERING By COMMANDER E. P. STATHAM, R.N. AUTHOR OF "THE STORY OF THE 'BRITANNIA,'" AND JOINT AUTHOR OF "THE HOUSE OF HOWARD" WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS New York JAMES POTT & COMPANY 1910 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN OX PREFACE A few words of explanation are necessary as to the pretension and scope of this volume. It does not pretend to be a history of privateering ; the subject is an immense one, teeming with technicalities, legal and nautical ; interesting, indeed, to the student of history, and never comprehensively treated hitherto, as far as the present author is aware, in any single work. The present object is not, however, to provide a work of reference, but rather a collection of true stories of privateering incidents, and heroes of what " " the French term la course ; and as such it is hoped that it will find favour with a large number of readers. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS Morten Hahn-Pedersen (éd.). Sjœklen 1995: increasingly fewer ports has been clear in Den• Arbog for Fiskeri- og Sofartsmuseet Saltvands- mark. One result of this trend is that Denmark's akvariet i Esbjerg. Esbjerg, DK: Fiskeri- og import and export trade has shifted steadily Sofartsmuseet Saltvandsakvariet i Esbjerg, 1996. westwards, in part because ports there are closer 160 pp., photographs, illustrations, tables, to the markets outside Denmark. Hahn-Pedersen figures, maps, references. DKr 198, hardback; predicts that in the future, only fourteen out of ISBN 87-87453-84-3. Denmark's ninety ports are likely to survive. These four articles all have a common In this, its eighth yearbook, the Fishery and Sea• theme, for they all focus on ports and their faring Museum in Esbjerg, Denmark follows tra• importance. In contrast, the fifth article — a ditional lines, publishing a collection of articles report of the results of a research project by where fisheries and maritime history intersect. Svend Tougaard, Nils Norgaard and Thyge However, in contrast to earlier editions, the Jensen — is devoted to the study of North Sea focus of Sjœklen 1995 is fairly narrow, with four seals and their behaviour. Among other things, of the five articles devoted to ports and trade. the researchers were able to judge the exact size In the lead article, Hanne Mathisen presents of the seal population in the Danish Waddensea. new evidence on trade between Denmark and Sjœklen 1995 should find a large market, as Norway in the seventeenth and eighteenth cen• it should appeal to both local historians and turies.