Un/Conditional Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

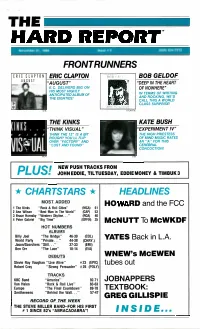

HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP in the HEART E.C

THE HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP IN THE HEART E.C. DELIVERS BIG ON OF NOWHERE" HIS MOST HIGHLY ANTICIPATED ALBUM OF IN TERMS OF WRITING AND ROCKING, WE'D THE EIGHTIES! CALL THIS A WORLD CLASS SURPRISE! ATLANTIC THE KINKS KATE BUSH NINNS . "THINK VISUAL" "EXPERIMENT IV" THINK THE 12" IS A BIT THE HIGH PRIESTESS ROUGH? YOU'LL FLIP OF MIND MUSIC RATES OVER "FACTORY" AND AN "A" FOR THIS "LOST AND FOUND" CEREBRAL CONCOCTION! MCA EMI JN OE HWN PE UD SD Fs RD OA My PLUS! ETTRACKS EDDIE MONEY & TIMBUK3 CHARTSTARS * HEADLINES MOST ADDED HOWARD and the FCC 1 The Kinks "Rock & Roll Cities" (MCA) 61 2 Ann Wilson "Best Man in The World" (CAP) 53 3 Bruce Hornsby "Western Skyline..." (RCA) 40 4 Peter Gabriel "Big Time" (GEFFEN) 35 McNUTT To McWKDF HOT NUMBERS ALBUMS Billy Joel "The Bridge" 46-39 (COL) YATES Back in L.A. World Party "Private. 44-38 (CHRY.) Jason/Scorchers"Still..." 37-33 (EMI) Ben Orr "The Lace" 18-14 (E/A) DEBUTS WNEW's McEWEN Stevie Ray Vaughan "Live Alive" #23(EPIC) tubes out Robert Cray "Strong Persuader" #26 (POLY) TRACKS KBC Band "America" 92-71 JOBNAPPERS Van Halen "Rock & Roll Live" 83-63 Europe "The Final Countdown" 89-78 TEXTBOOK: Smithereens "Behind the Wall..." 57-47 GREG GILLISPIE RECORD OF THE WEEK THE STEVE MILLER BAND --FOR HIS FIRST # 1 SINCE 82's "ABRACADABRA"! INSIDE... %tea' &Mai& &Mal& EtiZiraZ CiairlZif:.-.ZaW. CfMCOLZ &L -Z Cad CcIZ Cad' Ca& &Yet Cif& Ca& Ca& Cge. -

Mb. Tins Walters' Palm Toffee

LIGHTINt3-UP TIME 6.25 p.m. YESfERDAY*S WEATHER . Maximum' Temperature 71.8 Minimum Temperature 65.5 ^DE TABL-TFOR FEB. Rainfall Tree* Sunshine 9.9 hours Data Blab Wnter LQW Water Sua- Sua- til. P -. ' A.M. P.M. ris* set 4 9.39 9.55 3.16 4.00 7.13 7.55 £ljCH\ 011*1 VOL: 30 — NO. 29 HAMILTON. BERMUDA SATURDAY., FEBRUARY 4, 1950 4D PER COPY WOULD WIDEN COURT'S £36,905 VOTES PASSED Plan For Million Gallon FBI Chief Says H*Bomb POWERS FOR MINORS BY HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY Property Realisation Clause Kindley Terminal Facilities Water Reserve Is Placed Queried By Several M.CPs. Need Renovating, Extending Data Given RussianslBy 7 Before House Of Assembly WANT TO KNOW IF IT WILL QUESTI0N~0rTGA-0LS IS SET ASIDE TRUST TERMS LIMITED BY CHAIRMAN Food Regulations A plan to increase tankage The powers of the court in deal The House of Assembly yester faci—ties of Government ing with ^he realisation of pro day approved the expenditure of buildings and churches to pro Arrested Atom Scientist perty owned by minors will be £36,905, £3,000 of which was for Approved By vide a 1,000,000 gallon water widened if the Legislature agrees further subsidy for the Queen of reserve for public distribution WASHINGTON, Feb. 3, (Reu LONDON, Feb. 3 (Reuter).— to an amendment to the Minors Bermuda, £900 for repairs to the The Assembly during droughts was laid be ter). — Senator's quoted F.B.I, An employee at the British At Bill, now under consideration by airline terminal at. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typemiter face, Mile men may be ftom any type of cornputer printer. The quality of mis repmduction is dependent upori the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct @nt, colored or poor quality itlustrations and photographs, print Meedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignrnent can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manusuipt and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauttiarized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indikate the deletion. Oversize materials (e-g., maps, drawings, charb) are reproduced by sectiming the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and contirwing from left to n'ght in equal sedons with small werlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographie pnnts are available for any photographs or illustrations appeamg in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell 8 Howell Inforniaticri and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA 800-521- TRADE UNION INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY: EXPLORING THE UNEVEN DEVELOPMENT OF GRASSROOTS SOLIDARITY FUNDS WITHIN CANADIAN UNIONS by Karen M. Brown Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August, 1999 Copyright by Karen M. Brown, 1999 National Library Bibliothegue nationale m*I of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bi bliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 W Jlington Street 395. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

01 February 1987 CHART #554 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Good Times Shake You Down Revenge The Final 1 Jimmy Barnes & INXS 21 Gregory Abbott 1 Eurythmics 21 Wham Last week 9 / 4 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 40 / 2 weeks CBS Last week 1 / 23 weeks Platinum / RCA Last week 18 / 22 weeks Platinum / SONY Ain't Nothin' Going On But The Rent Heartache All Over The World Genesis Infected 2 Gwen Guthrie 22 Elton John 2 Genesis 22 The The Last week 1 / 5 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 32 / 6 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 4 / 99 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Last week 28 / 6 weeks CBS Walk Like An Egyptian Bye Baby Every Breath You Take - Singles Notorious 3 The Bangles 23 Ruby Turner 3 The Police 23 Duran Duran Last week 2 / 8 weeks FESTIVAL Last week - / 1 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 2 / 5 weeks Platinum / FESTIVAL Last week 20 / 4 weeks EMI I Love My Leather Jacket True Blue Graceland Brothers In Arms 4 The Chills 24 Madonna 4 Paul Simon 24 Dire Straits Last week 4 / 3 weeks Flying Nun Last week 27 / 13 weeks WEA Last week 3 / 15 weeks Platinum / WEA Last week 35 / 81 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM You Oughta Be In Love Missionary Man Fore Raising Hell 5 Dave Dobbyn 25 Eurythmics 5 Huey Lewis & The News 25 Run DMC Last week 6 / 4 weeks CBS Last week 28 / 12 weeks RCA Last week 7 / 9 weeks Platinum / FESTIVAL Last week 27 / 5 weeks Gold / POLYGRAM Don't Leave Me This Way The Way It Is True Colours Good To Go Lover 6 The Communards 26 Bruce Hornsby And The Range 6 Cyndi Lauper 26 Gwen Guthrie Last week 5 / 7 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 23 / 4 weeks RCA Last week 6 / 15 weeks -

Historic Preservation and the New Deal

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Restoring America: Historic Preservation and the New Deal Stephanie E. Gray Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Gray, S. E.(2019). Restoring America: Historic Preservation and the New Deal. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5433 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORING AMERICA: HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND THE NEW DEAL by Stephanie E. Gray Bachelor of Arts Mount Holyoke College, 2013 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2016 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Lauren Rebecca Sklaroff, Major Professor Robert Weyeneth, Committee Member Patricia Sullivan, Committee Member Lydia Mattice Brandt, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Stephanie E. Gray, 2019 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION For my mother, Lucy Gray. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is said that writing a dissertation is a solitary venture. While that is true to some extent, no dissertation is completed without the support of many people in many places. First, I extend my deepest gratitude to my wonderful committee. To my advisor, Lauren Sklaroff, tremendous thanks for accepting me as a student and teaching me to think and write like a cultural historian. -

Of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2011/August/ Notes Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2011/August/ Notes

AL Direct, August 3, 2011 Contents American Libraries Online ALA News Booklist Online Division News Awards Seen Online Tech Talk E-Content Books and Reading The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | August 3, 2011 Actions & Answers New This Week Calendar American Libraries Online Third time is the charm for Troy “This is one of the best days I’ve had in two years!” exulted Cathleen Russ, director of Troy (Mich.) Public Library, the morning after some 58% of voters saved the library from closing permanently by approving a five-year operating millage. The August 2 special election was the third library referendum held there in the past few years; voters had rejected the previous measures, albeit by narrower margins the second time around. The outcome had remained uncertain until the final returns late in the day.... American Libraries news, Aug. 3; Detroit News, Aug. 3; Troy (Mich.) Patch, Aug. 2 Missouri high school bans Slaughterhouse-Five Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five and Sarah Ockler’s YA novel Twenty Boy Summer have been banned from a Missouri high school curriculum and library after a local resident complained that they teach principles contrary to the Bible. The Republic High School board voted 4–0 July 26 to remove the books, although they chose to retain Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, which had also been challenged by Wesley Scroggins, an associate professor at Missouri State University. Ockler responded to the decision in a blog post.... AL: Censorship Watch, Aug. 3; Sarah Ockler, Author, July 26 The case for graphic novels in education Jesse Karp writes: “Perhaps we’re past the point of having to explain that graphic novels, with their knack for attracting reluctant readers and hitting developmental sweet spots, have a legitimate place on library shelves. -

Rebecca Henry -Solo Acoustic Song List

Rebecca Henry - Solo Acoustic Song List Chilled vibe All I want is You – U2 Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Amazed - Lonestar Amazing – Alex Lloyd Angels -RoBBie Williams Angel of Mine - Monica Are you strong enough – Sheryl Crow Better Be Home Soon – Crowded House Better Together – Jack Johnson Be My Downfall – Del Amitri Breathe – Faith Hill Burn – Tina Arena Buses and Trains – Bachelor Girl BuBBly – ColBie Caillat Candle In The Wind – Elton John Count On Me – Bruno Mars Country Roads – John Denver Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Daniel – Elton John Dreams – Fleetwood Mac Dock Of The Bay Don’t Dream It’s Over – Crowded House Even When I’m sleeping – Leonardo’s Bride Every Rose Has It’s Thorn – Poison Englishman In New York - Sting Father and Son – Cat Stevens Fall at Your Feet – Crowded House Fallin’ For You – ColBie Coillat Fast Car – Tracey Chapman Fire & Rain – James Taylor Fields Of Gold – Sting/Eva Cassidy Flame Trees – Cold Chisel Gypsy – Suzan Vega Gypsy – Fleetwood Mac Give Me One Reason – Tracey Chapman Grow Old With You – Wedding Singer Soundtrack Head over Feet – Alanis Morrisette Here Without You – 3 Doors Down Help – John Farhnam /Beatles Hey There Delilah - Hold On – Wilson Phillips House Of The Rising Son – Bob Dylan If I Ain’t Got You – Alicia Keys Imagine – John Lennon I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For – U2 I Won’t Let Go – James Morrison Just the Way You Are – Bruno Mars Kissing You - Desiree Kiss From A Rose - Seal Landslide – Fleetwood Mac La Isla Bonita – Madonna Lean On Me – Bill Withers Little Bird- Annie -

Guns N' Roses Entity Partnership Citizenship California Composed Of: W

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA966168 Filing date: 04/10/2019 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Guns N' Roses Entity Partnership Citizenship California Composed Of: W. Axl Rose Saul Hudson Michael "Duff" McKagan Address c/o LL Management Group West, LLC 5950 Canoga Ave., Ste. 510 Woodland Hills, CA 91367 UNITED STATES Attorney informa- Jill M. Pietrini Esq. tion Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP 1901 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1600 Los Angeles, CA 90067 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], MDan- [email protected], [email protected], RLHud- [email protected] 310-228-3700 Applicant Information Application No 87947921 Publication date 03/12/2019 Opposition Filing 04/10/2019 Opposition Peri- 04/11/2019 Date od Ends Applicant ALDI Inc. 1200 N. Kirk Road Batavia, IL 60510 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 029. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: cheese, namely, cheddar cheese Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act Section 2(d) False suggestion of a connection with persons, Trademark Act Section 2(a) living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or brings them into contempt, or disrep- ute Mark Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Application/ Registra- NONE Application Date NONE tion No. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5030

Stockton's news source since 1973 Maxiay Decemte 10,2001 The independent student newspaper of the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey Volurne 61 Number 11 Stockton Student arrested in Housing I robbery alumna Shaun Reilly County CrimeStoppers. motor vehicle in parking lot seven. Rodriguez The Argo When the Police arrested Smith, they also was arrested as a John Doe because he had no The Richard Stockton College Police have picked up Corey Dameo on trespassing and identification at the time of the arrest. He was battles charged James L. Smith with robbery. an outstanding warrant. Dameo is a student later found to be a 21-year-old male who had According to Stockton Police Chief Thomas that was banned from entering the housing just been released from the Atlantic County Kinzer, on October 26th a facilities. He was with Smith at the time of Justice Facility. The Stockton Police charged with AIDS non-student visiting others their arrest. He was also detained for an active Rodriguez with theft from a motor vehicle. Police in a Housing I apartment warrant for a motor vehicle violation in Dan Grote Bioner was accosted by Smith and Stafford Township. Drug and Alcohol Offenses The Argo an another assailant. The Rui D. Costa, a 20 year old student from The Office of Housing and assailants allegedly stole personal property On November 12, a caller reported to the Rowan University, was charged with posses Residential Life sponsored a pro and cash from the unnamed victim by both police that a suspicious person had aban sion of controlled and dangerous substances gram in recognition of World physical force and threats. -

Eurythmics Thorn in My Side Mp3, Flac, Wma

Eurythmics Thorn In My Side mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Thorn In My Side Country: US Released: 1986 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1911 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1323 mb WMA version RAR size: 1366 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 937 Other Formats: AUD XM WMA WAV DXD AHX MP1 Tracklist A Thorn In My Side 4:12 B In This Town 3:44 Credits Artwork By [Design] – Timothy Eames Artwork By [Photography] – Jeff Katz Backing Vocals – Bernita Turner, Joniece Jamison Bass – John McKenzie Drums – Clem Burke Engineer [1st Assistant Engineer] – Fred Defaye Engineer [2nd Assistant Engineer] – Serge Pauchard Engineer [Mix] – Jon Bavin, Manu Guiot Guitar, Vocals – David A. Stewart Keyboards – Patrick Seymour Other [Creative Co-ordination] – Billy Poveda Producer – David A. Stewart Saxophone, Harmonica – Jimmy "Z" Zavala* Vocals – Annie Lennox Written-By – Lennox*, Stewart* Notes (P) 1986, RCA/Ariola Ltd. From the "Revenge" album, AJL1-5847. Side A recorded at Conny's Studio, Cologne & Studio Grand Armée, Paris. Side B recorded at Manu's Party. Actual duration for Track A is listed above. Printed duration is 4:45. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Thorn In My Side (7", DA 8 Eurythmics RCA DA 8 UK 1986 Single) Thorn In My Side RCA Australia & TDS 345 Eurythmics TDS 345 1986 (12") Victor New Zealand Thorn In My Side (7", PB40899 Eurythmics RCA PB40899 Europe 1986 Single) Thorn In My Side (7", RPS-227 Eurythmics RCA RPS-227 Japan 1986 Promo) 5058-7-RAA Thorn In My Side (7", 5058-7-RAA Eurythmics RCA US 1986 (5058-7-R) Promo) (5058-7-R) Related Music albums to Thorn In My Side by Eurythmics Eurythmics - Beethoven Kiki Dee - Another Day Comes (Another Day Goes) Eurythmics - Revenge Eurythmics - Right By Your Side Eurythmics - You Have Placed A Chill In My Heart Eurythmics - There Must Be An Angel (Playing With My Heart) Eurythmics - Shame Eurythmics - Revival Eurythmics - We Too Are One Eurythmics - Right By Your Side = Justo A Tu Lado Eurythmics - Touch Eurythmics - Savage. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

15 February 1987 CHART #556 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Good Times You're The Voice Revenge Kev's Back 1 Jimmy Barnes & INXS 21 John Farnham 1 Eurythmics 21 Kevin Bloody Wilson Last week 1 / 6 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 20 / 7 weeks RCA Last week 1 / 25 weeks Platinum / RCA Last week 18 / 5 weeks CBS You Oughta Be In Love Hip To Be Square Genesis Get Close 2 Dave Dobbyn 22 Huey Lewis & The News 2 Genesis 22 The Pretenders Last week 2 / 6 weeks CBS Last week 14 / 6 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 3 / 101 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Last week 22 / 10 weeks Gold / WEA French Kissin' Walk This Way Graceland The Final 3 Debbie Harry 23 Run DMC feat. Aerosmith 3 Paul Simon 23 Wham Last week 6 / 3 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 19 / 9 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 4 / 17 weeks Platinum / WEA Last week 20 / 24 weeks Platinum / SONY Shake You Down Love Will Conquer All Every Breath You Take - Singles On The Beach 4 Gregory Abbott 24 Lionel Richie 4 The Police 24 Chris Rea Last week 11 / 4 weeks CBS Last week 43 / 4 weeks RCA Last week 2 / 7 weeks Platinum / FESTIVAL Last week 27 / 22 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Ain't Nothin' Going On But The Rent Lady In Red Footrot Flat: The Dogs Tale OST Liverpool 5 Gwen Guthrie 25 Chris De Burgh 5 Dave Dobbyn 25 Frankie Goes to Hollywood Last week 3 / 7 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 28 / 15 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 5 / 6 weeks Platinum / CBS Last week 25 / 5 weeks Gold / FESTIVAL I Wanna Wake Up With You We Love You Dancing On The Ceiling Raising Hell 6 Boris Gardiner 26 Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark 6 Lionel Richie 26 Run DMC Last -

COVID-19 Impacts on Tourism-Related Businesses: Thoughts and Concerns

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research 5-2020 COVID-19 Impacts on Tourism-Related Businesses: Thoughts and Concerns Glenna Hartman Norma P. Nickerson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y COVID-19 Impacts on Tourism-Related Businesses: 2020 Thoughts and Concerns COVID-19 Impacts on Tourism-Related Businesses: Thoughts and Concerns MT Expression Research Report 2020-6 Glenna Hartman & Norma Nickerson, Ph.D. 5/21/2020 Institute for Tourism & Recreation Research College of Forestry and Conservation The University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812 www.itrr.umt.edu Copyright© 2020 Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research. All rights reserved. 1 COVID-19 Impacts on Tourism-Related Businesses: 2020 Thoughts and Concerns Abstract The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has been detrimental for both the health and the economy of Montanans and the entire globe. Many of Montana businesses, especially the travel-related businesses, were shut down from mid-March to the end of May. All non-essential travel stopped. The impact on businesses was felt statewide. This report focuses on the open-ended responses within the third round of business surveys conducted by the Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research (ITRR) at the University of Montana. The survey was conducted in the height of Montana’s shut-down to capture the thoughts and concerns of business owners in the travel industry. Of the 440 survey respondents, the majority say this will be a long, slow recovery and nearly half of the businesses say they cannot last over 6 months if this continues.