Period 1: 1491-1607 A. Explain the Context for European Encounters in the Americas from 1491 to 1607

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

Struggle for North America Prepare to Read

0120_wh09MODte_ch03s3_s.fm Page 120 Monday, June 4, 2007 10:26WH09MOD_se_CH03_S03_s.fm AM Page 120 Monday, April 9, 2007 10:44 AM Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION 3 Instruction 3 A Piece of the Past In 1867, a Canadian farmer of English Objectives descent was cutting logs on his property As you teach this section, keep students with his fourteen-year-old son. As they focused on the following objectives to help used their oxen to pull away a large log, a them answer the Section Focus Question piece of turf came up to reveal a round, and master core content. 3 yellow object. The elaborately engraved 3 object they found, dated 1603, was an ■ Explain why the colony of New France astrolabe that had belonged to French grew slowly. explorer Samuel de Champlain. This ■ Analyze the establishment and growth astrolabe was a piece of the story of the of the English colonies. European exploration of Canada and the A statue of Samuel de Champlain French-British rivalry that followed. ■ Understand why Europeans competed holding up an astrolabe overlooks Focus Question How did European for power in North America and how the Ottawa River in Canada (right). their struggle affected Native Ameri- Champlain’s astrolabe appears struggles for power shape the North cans. above. American continent? Struggle for North America Prepare to Read Objectives In the 1600s, France, the Netherlands, England, and Sweden Build Background Knowledge L3 • Explain why the colony of New France grew joined Spain in settling North America. North America did not Given what they know about the ancient slowly. -

Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States Mahmoud Y

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 1998 Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States Mahmoud Y. El-Najjar Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan Thomas M. J. Mulinski Chicago, Illinois Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard El-Najjar, Mahmoud Y.; Mulinski, Thomas M. J.; and Reinhard, Karl, "Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States" (1998). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in MUMMIES, DISEASE & ANCIENT CULTURES, Second Edition, ed. Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn, and Theodore A. Reyman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 7 pp. 121–137. Copyright © 1998 Cambridge University Press. Used by permission. Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States MAHMOUD Y. EL-NAJJAR, THOMAS M.J. MULINSKI AND KARL J. REINHARD Mummification was not intentional for most North American prehistoric cultures. Natural mummification occurred in the dry areas ofNorth America, where mummies have been recovered from rock shelters, caves, and over hangs. In these places, corpses desiccated and spontaneously mummified. In North America, mummies are recovered from four main regions: the south ern and southwestern United States, the Aleutian Islands, and the Ozark Mountains ofArkansas. -

Latin America's Missing Middle

Latin America’s missing middle: Rebooting inclusive growth inclusive Rebooting middle: missing Latin America’s Latin America’s missing middle Rebooting inclusive growth May 2019 McKinsey Global Institute Since its founding in 1990, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has sought to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. As the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI aims to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labor markets, the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology and innovation, and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed the digital economy, the impact of AI and automation on employment, income inequality, the productivity puzzle, the economic benefits of tackling gender inequality, a new era of global competition, Chinese innovation, and digital and financial globalization. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company senior partners: Jacques Bughin, Jonathan Woetzel, and James Manyika, who also serves as the chairman of MGI. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, Anu Madgavkar, Jan Mischke, Sree Ramaswamy, and Jaana Remes are MGI partners, and Mekala Krishnan and Jeongmin Seong are MGI senior fellows. -

Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas. Justin Garrett Orh Ton East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2007 The econdS Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas. Justin Garrett orH ton East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Horton, Justin Garrett, "The eS cond Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2025. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2025 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Second Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas ___________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History ______________________________________ by Justin Horton August 2007 ____________________________________ Melvin Page, Chair Tom Lee Doug Burgess Keywords: Manifest Destiny, Brazil, Mexico, colonization, emigration, Venezuela, Confederate States of America, Southern Nationalism ABSTRACT The Second Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas by Justin Horton At the close of the American Civil War some southerners unwilling to remain in a reconstructed South, elected to immigrate to areas of Central and South America to reestablish a Southern antebellum lifestyle. -

The Americas and Oceania Ben06937.Ch21 538-563.Qxd 8/9/07 3:36 PM Page 539

ben06937.Ch21_538-563.qxd 8/9/07 3:36 PM Page 538 Worlds Apart: 21 The Americas and Oceania ben06937.Ch21_538-563.qxd 8/9/07 3:36 PM Page 539 States and Empires in Mesoamerica States and Empires in South America and North America The Coming of the Incas The Toltecs and the Mexica Inca Society and Religion Mexica Society Mexica Religion The Societies of Oceania Peoples and Societies of the North The Nomadic Foragers of Australia The Development of Pacific Island Societies In November 1519 a small Spanish army entered Tenochtitlan, capital city of the Aztec empire. The Spanish forces came in search of gold, and they had heard many reports about the wealth of the Aztec empire. Yet none of those reports prepared them adequately for what they saw. Years after the conquest of the Aztec empire, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier in the Span- ish army, described Tenochtitlan at its high point. The city itself sat in the water of Lake Tex- coco, connected to the surrounding land by three broad causeways, and as in Venice, canals allowed canoes to navigate to all parts of the city. The imperial palace included many large rooms and apartments. Its armory, well stocked with swords, lances, knives, bows, arrows, slings, armor, and shields, attracted Bernal Díaz’s professional attention. The aviary of Tenochti- tlan included eagles, hawks, parrots, and smaller birds in its collection, and jaguars, mountain lions, wolves, foxes, and rattlesnakes were noteworthy residents of the zoo. To Bernal Díaz the two most impressive sights were the markets and the temples of Te- nochtitlan. -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

Looking Ahead

THE AMERICAS IN MOTION: Looking Ahead 30TH ANNIVERSARY SOL M. LINOWITZ FORUM COMMEMORATIVE VOLUME APRIL 2013 YEARS SHAPING POLICY DEBATE FOR ACTION YEARS SHAPING POLICY DEBATE FOR ACTION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Michelle Bachelet, Co-Chair, Chile Carla A. Hills, Co-Chair, United States Enrique Iglesias, Co-Vice Chair, Uruguay Thomas F. McLarty III, Co-Vice Chair, United States David de Ferranti, Treasurer, United States Peter D. Bell, Chair Emeritus, United States Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Chair Emeritus, Brasil Ricardo Lagos, Chair Emeritus, Chile Alicia Bárcena, Mexico Brian O’Neill, United States Francis Fukuyama, United States Pierre Pettigrew, Canada L. Enrique García, Bolivia Jorge Quiroga, Bolivia Donna J. Hrinak, United States Marta Lucía Ramírez, Colombia Marcos Jank, Brasil Eduardo Stein, Guatemala Jim Kolbe, United States Martín Torrijos, Panama Thomas J. Mackell, Jr., United States Elena Viyella de Paliza, Dominican Republic M. Peter McPherson, United States Ernesto Zedillo, Mexico Billie Miller, Barbados Michael Shifter President The Americas in Motion: Looking Ahead 30TH ANNIVERSARY SOL M. LINOWITZ FORUM COMMEMORATIVE VOLUME i Contents Preface by Michael Shifter ....................................................................................................iv Foreword by Ricardo Lagos ..................................................................................................v 1. Rethinking US-Latin American Relations: Thirty Years of Transformations Abraham F. Lowenthal, University of Southern California..................................................1 -

A Century of Public Health in the Americas

Chapter 1 A Century of Public Health in the Americas Health is a powerful tool for making a safer and INTRODUCTION durable world for all. For those who really want to ‘‘talk the talk’’ and ‘‘walk the walk,’’ it is a moral The Region of the Americas is a geographically vast, imperative to make inequities visible. (1) historically rich, and ubiquitously beautiful land. It Mirta Roses Periago, also is a region of stark and contrasting realities—in Director, Pan American Health Organization its population’s health and human development and Health in the Americas, 2012 Edition: Regional Volume N ’ Pan American Health Organization, 2012 HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS, 2012 N REGIONAL VOLUME in the interplay of social, economic, environmental, predominantly rural to being predominantly urban and political determinants. These disparate traits (4, 5). have been increasingly scrutinized, documented, The Region of the Americas has made and targeted since the Pan American Health remarkable strides in population health. In the last Organization (PAHO) came into being in 1902. 110 years, the infant mortality rate decreased from Without question, in the intervening 110 years the 167.4 per 1,000 live births in 1900 (229.1 in Latin Region has made remarkable strides in improving America and the Caribbean; 145.0 in North the health of its people. But inequities persist, and America) to 15.2 in 2010 (20.3 in Latin America this fact will inspire and guide the Region’s collective and the Caribbean; 6.6 in North America): that is, effort to usher in a better future—a future that is on average, an astounding 11-fold reduction (22-fold healthier, wealthier, fairer, and more equitable. -

Who Are Indigenous Peoples? It Is Estimated That There Are More Than 370 Million Indigenous People Spread Across 70 Countries Worldwide

FACTSHEET Who are indigenous peoples? It is estimated that there are more than 370 million indigenous people spread across 70 countries worldwide. Practicing unique traditions, they retain social, cultural, economic and political characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live. Spread across the world from the Arctic to the South Pacific, they are the descendants - according to a common definition - of those who inhabited a country or a geographical region at the time when people of different cultures or ethnic origins arrived. The new arrivals later became dominant through conquest, occupation, settlement or other means. Among the indigenous peoples are those of the Americas (for example, the Lakota in the USA, the Mayas in Guatemala or the Aymaras in Bolivia), the Inuit and Aleutians of the circumpolar region, the Saami of northern Europe, the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders of Australia and the Maori of New Zealand. These and most other indigenous peoples have retained distinct characteristics which are clearly different from those of other segments of the national populations. Understanding the term “indigenous” Considering the diversity of indigenous peoples, an official definition of “indigenous” has not been adopted by any UN-system body. Instead the system has developed a modern understanding of this term based on the following: • Self- identification as indigenous peoples at the individual level and accepted by the community as their member. • Historical continuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies • Strong link to territories and surrounding natural resources • Distinct social, economic or political systems • Distinct language, culture and beliefs • Form non-dominant groups of society • Resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities. -

America, Africa, and Europe Before 1500

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Module 1 America, Africa, and Europe before 1500 Essential Question Why might a U.S. historian study the Americas, Africa, and Europe before 1500? About the Photo: American buffalo were In this module you will learn the histories of three regions—the a vital food source for many Native Americas, West Africa, and Europe—whose people would come together American groups. and forever change North America. What You Will Learn … Lesson 1: The Earliest Americans.. 6 Explore ONLINE! The Big Idea Native American societies developed across North and VIDEOS, including... South America. • Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations Lesson 2: Native American Cultures .. 11 The Big Idea Many diverse Native American cultures developed • Corn across the different geographic regions of North America. • Machu Picchu Lesson 3: Trading Kingdoms of West Africa . 19 • Salt The Big Idea Using trade to gain wealth, Ghana, Mali, and Songhai • Origins of Western Culture were West Africa’s most powerful kingdoms. • Rome Falls Lesson 4: Europe before 1500.. 23 • The First Crusade The Big Idea New ideas and trade changed Europeans’ lives. Document-Based Investigations Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Interactive Map: Migrations of Early People Image with Hotspots: The Chinook Image Carousel: Empires of Gold and Salt 2 Module 1 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events Beginnings–AD 1500 Explore ONLINE! Module Events World 38,000 BC c. 38,000–10,000 BC Paleo-Indians migrate to the Americas. c. 5000 BC Communities in Mexico 5000 BC cultivate corn. -

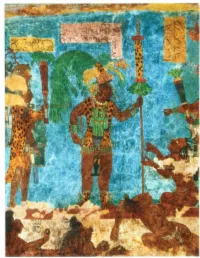

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields.