Gordon V. Aztec Brewing Company Roger J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beer History: 3 Nearly-Forgotten San Diego Beer Pioneers | Serious Eats Beer History: 3 Nearly-Forgotten San Diego Beer Pioneers

3/30/2021 Beer History: 3 Nearly-Forgotten San Diego Beer Pioneers | Serious Eats Beer History: 3 Nearly-Forgotten San Diego Beer Pioneers LISA GRIMM While San Diego is known as a craft beer destination, being home to Stone, Ballast Point, AleSmith, and many more, there was a thriving brewing scene long before those breweries appeared. 19th- and early-20th century San Diego's breweries were a little smaller and rougher, but they were a key part of their city. And although San Francisco dominated early commercial brewing in California—major Bay Area breweries such as Fredericksburg and Philadelphia Brewery had outposts in San Diego—homegrown businesses made their own marks, not just on the industry, but on the city itself. Here is a brief look at three nearly-forgotten San Diego beer pioneers. San Diego Brewing Company Alonzo Horton , who developed much of what became modern San Diego, founded San Diego Brewing Company in the late 1890s. Soon, business was thriving—demand was such that a 5-ton ice-making machine was installed, as well as a stand-alone bottling house (pictured here ). By 1909, the company changed its name to the San Diego Consolidated Brewing Company, and was valued at more than $500,000. But despite brewing a popular, successful product, the political climate was not favorable to the company's continued good fortunes—by 1913, Arizona had passed its own anti-alcohol law, and the company led suit against the Atchinson, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad for refusing to carry their near-beer products to the now-dry state (previously a reliable consumer). -

5.1.2 Del Mar Municipal Code

Del Mar City Hall/Town Hall Project Historic Building Survey of the City Hall Buildings at 1050 Camino Del Mar Del Mar, California Prepared for Prepared by City of Del Mar RECON Environmental, Inc. 1050 Camino Del Mar 1927 Fifth Avenue Del Mar, CA 92014 San Diego, CA 92101-2358 P 619.308.9333 F 619.308.9334 RECON Number 7786 July 8, 2015 Harry J. Price, Architectural Historian THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK. Del Mar City Hall/Town Hall Project Historic Building Survey of the City Hall Buildings at 1050 Camino Del Mar NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA BASE INFORMATION Author: Harry J. Price, Jr. Consulting Firm: RECON Environmental, Inc. 1927 Fifth Avenue San Diego, CA 92101-2358 Report Date: July 8, 2015 Report Title: Historic Building Survey of the City Hall Buildings at 1050 Camino Del Mar in the City of Del Mar, California Submitted to: City of Del Mar Contract Number: RECON Number 7786 U.S.G.S. Quadrangle Map: Del Mar, Calif., 7.5-minute series, 1996 edition Acreage: N/A Keywords: Del Mar, administration building, 1920s, building evaluation, APN 300-093-0200, City of Del Mar Historical Resources Survey ABSTRACT This report presents the methods and results of a historic building evaluation of the City Hall buildings at 1050 Camino Del Mar in the City of Del Mar. The evaluations were conducted to determine the significance of two existing City Hall buildings that are over 50 years old that will be impacted by the proposed Del Mar City Hall/Town Hall Project on the existing City administration property. -

The Journal of San Diego History Vol 53, 2007, Nos 1 & 2

The Jour na l of San Diego History Publication of The Journal of San Diego History has been partially funded by generous grants from the Joseph W. Sefton Foundation; Quest for Truth Foundation of Seattle, Washington, established by the late James G. Scripps; and an anonymous friend and supporter of the Journal. Publication of this issue of The Journal of San Diego History has also been supported by a grant from “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation. The San Diego Historical Society is able to share the resources of four museums and its extensive collections with the community through the generous support of the following: City of San Diego Commission for Art and Culture; County of San Diego; foundation and government grants; individual and corporate memberships; corporate sponsorship and donation bequests; sales from museum stores and reproduction prints from the Booth Historical Photograph Archives; admissions; and proceeds from fund-raising events. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front Cover: Robinson-Rose House built in Old Town San Diego in 1874; presently the Old Town San Diego State Historic Park Visitors Center. Back Cover: Thomas Sefton with his collection of toy trains, September 4, 1958. ©SDHS UT #85:7793, Union-Tribune Collection. Cover Design: Allen Wynar The Journal of San Diego History Volume 53 Winter/Spring 2007 numbers 1 & 2 IRIS H. -

Craft Beer in San Diego Society by Ernie Liwag

The Journal of San Diego History Craft Beer in San Diego Society Ernie Liwag Winner of the 2006 Joseph L. Howard Fund Award This is grain, which any fool can eat, but for which the Lord intended a more divine means of consumption. Let us give praise to our maker and glory to his bounty by learning about….Beer! Dave Thomas, President, American Society of Brewing Chemists The United States has recently witnessed a revival in craft brewing operations, microbrewing, homebrewing, and brewpubs. Craft brewers are, by definition of the Brewers Association, “small, independent and traditional.”1 They produce fewer than 2 million barrels of beer annually; less than 25 percent of their brewery is owned or controlled by a non-craft brewer; and they produce a high proportion of all malt beers. The first microbrewery started in Sonoma County, California, in 1976. There are now more than 1,400 establishments nationwide with many highly successful operations in San Diego.2 Craft beer thrives at a time when beer production, nationally, is on the decline. The top three brewers, Anheuser-Busch, Miller Brewing and Coors, have been showing steady decline in sales and production but they continue to dominate the industry. John Cavanagh, author of Alcoholic Beverages: Dimensions of Corporate Power (1985), pointed out that the national brewers have developed market strategies, including pricing below cost, in order to capture a greater market share. They rely on their gargantuan advertising investments and brand royalties to make up the lost profit.3 His work, published only two years after brew pub operations became legal in California, did not address the rise of craft beer so its impact remains to be seen. -

Ancient Mexico in United States Art and Visual Culture, 1933-1945

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FORGING A NEW WORLD NATIONALISM: ANCIENT MEXICO IN UNITED STATES ART AND VISUAL CULTURE, 1933-1945 Breanne Robertson, Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 Directed By: Associate Professor Renée Ater, Department of Art History and Archaeology Professor Sally M. Promey, Department of American Studies, Yale University, formerly Department of Art History and Archaeology, University of Maryland Between 1933 and 1945, Americans redefined their cultural identity within a hemispheric context and turned toward Mexican antiquity to invent a non-European national mythos. This reconfiguration of ancient Mexican history and culture coincided with changes in U.S. foreign policy regarding Latin American nations. In his inaugural address on March 4, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt launched the Good Neighbor Policy, hoping to build an international alliance with Latin American countries that would safeguard the Western hemisphere from the political and economic crises in Europe. As part of these efforts, the government celebrated Mesoamerican civilization as evidence of a great hemispheric heritage belonging also to United States citizens. These historical circumstances altered earlier American views of ancient Mexico as simultaneously a preindustrial paradise of noble savages and an uncivilized site of idolatry, revolution, and human sacrifice. My dissertation examines this official reinterpretation of American past and present reality under the Good Neighbor Policy. Specifically, I consider the portrayal of ancient Mexico in United States art as a symbol of pan-American identity in order to map the ideological contours of U.S. diplomacy and race relations. The chapters of the dissertation present a series of case studies, each devoted to a different facet of the international discourse of U.S.-led pan-Americanism as it was internally conceived and domestically disseminated. -

Relocation Guide

SanRelocation Diego Guide toWelcome San Diego San Diego: America’s Finest City ............................2 Central San Diego .................................................. 13 North County Coastal .............................................19 North County Inland ...............................................23 East County ............................................................ 27 South County ..........................................................31 Education ............................................................... 35 Golf Courses ...........................................................39 Shopping ................................................................40 Attractions .............................................................. 41 Wineries ..................................................................47 Breweries ................................................................51 Medical Services .....................................................57 Taxes & Licenses/Media & Stations ........................59 Parks & Preserves ................................................... 61 Top 50 Trails ........................................................... 63 Transportation ........................................................ 66 1 America’s finest City During the 1920s and ’30s, pioneering aviators like Charles Lindbergh and Claude Ryan helped create and secure San Diego’s future as a military and defense center. Following the Second World War, the city saw its geography and climate as a magnet -

QUAFF Year in Review

About QUAFF Quality Ale and Fermentation Fraternity (QUAFF) is a 501(c)(7) organi- zation made up of men and women dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of homebrewing and beer evaluation in the greater San Diego area. We share knowledge, methods, new brewpub and micro- brewery discoveries, and good homebrew at monthly meetings and special events. From it’s humble beginnings with only a handful of members, QUAFF has grown to over 300 active members. Having changed the monthly meeting location numerous times to accommodate the growing size of the club, QUAFF meets on the fourth Tuesday of each month and takes up the entire outdoor patio space at Randy Jones All-American Grill in Mission Valley, San Diego, CA. In addition to the monthly meetings, QUAFF manages two large homebrew competitions every year. America’s Finest Homebrew Competition (AFC) occurs every February and QUAFF manages one of the National Homebrew Competition Round 1 locations. As part of the San Diego brewing scene, there is no shortage of volunteer opportunities for QUAFF mem- bers to participate in beer festivals, homebrew competitions and other beer related events. For exam- ple, Stone Brewing has their anniversary party every year, requiring hundreds of volunteers, and the en- tire proceeds are distributed to four local charities. This year, the 17th anniversary, Stone announced that it had raised over one and a half million dollars through the anniversary event alone. Every year QUAFF participates in Big Brew Day and Mead Day. This year’s Big Brew Day was spent at White Labs and Mead Day was held at a QUAFF members house, the Bixby’s. -

Los Años Olvidados De Bibendum La Etapa Americana De Michelin En Milltown

Los años olvidados de Bibendum La etapa americana de Michelin en Milltown Diseño, ilustración y publicidad en las compañías del neumático (1900-1930) Pablo Medrano Bigas ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

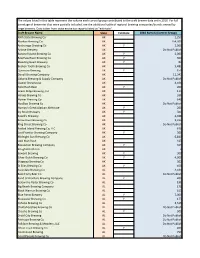

H.710: National Barrelage Data

The values listed in this table represent the volume each control group contributed to the craft brewer data set in 2016. For full barrelage of breweries that were partially included, see the additional table of regional brewing companies/brands owned by large brewers. Data taken from state excise tax reports listed as "estimate". Craft Brewer Name State Estimate 2016 Barrels (Control Group) 49th State Brewing Co AK 1,250 Alaskan Brewing Co AK 154,300 Anchorage Brewing Co AK Y 2,000 Arkose Brewery AK Do Not Publish Baranof Island Brewing Co AK Y 2,000 BearPaw River Brewing Co AK Y 300 Bleeding Heart Brewery AK Y 80 Broken Tooth Brewing Co AK 5,481 Cynosure Brewing AK Y 150 Denali Brewing Company AK 11,341 Gakona Brewing & Supply Company AK Do Not Publish Glacier Brewhouse AK 4,101 Gold Rush Beer AK Y 200 Grace Ridge Brewing, Inc AK 110 Haines Brewing Co AK 336 Homer Brewing Co AK 648 HooDoo Brewing Co AK Do Not Publish Humpy's Great Alaskan Alehouse AK Y 200 Icy Strait Brewery AK Y 500 Kassik's Brewery AK 2,048 Kenai River Brewing Co AK 2,236 King Street Brewing Co AK Do Not Publish Kodiak Island Brewing Co, LLC AK 678 Last Frontier Brewing Company AK Y 300 Midnight Sun Brewing Co AK 6,840 Odd Man Rush AK 425 Resolution Brewing Company AK Y 315 RoughWoods Inn AK 2 Seward Brewing AK Y 300 Silver Gulch Brewing Co AK Y 4,000 Skagway Brewing Co AK 302 St Elias Brewing Co AK Y 450 Avondale Brewing Co AL 4,630 Back Forty Beer Co AL Do Not Publish Band of Brothers Brewing Company AL Y 400 Below the Radar Brewing Co AL 196 Big Beach Brewing Company -

Fast Facts Short Version

1200 Third Avenue, Suite 924 San Diego, California 92101-4106 619.236.6800 • www.sandiego.gov/arts-culture/ Fast Facts Aztec Brewing Company Rathskeller Collection PROJECT OVERVIEW The original Aztec Brewing Company was established in 1921 in Mexicali, Mexico during Prohibition in the United States. It was the maker of ABC Beer, which was very popular in Mexico, and won a gold medal at the 1929 International Exposition in Seville, Spain. When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the Aztec Brewing Company moved north to the Barrio Logan neighborhood of San Diego, and into a building on Main Street formerly occupied by a tire factory. After an extensive Aztec Brewing Co. building with rathskeller on the right, c. 1935, © San Diego History Center remodel that included the installation of technologically advanced brewing equipment, the Aztec Brewing Company flourished, becoming one of the largest breweries on the West Coast. The Aztec Brewing Company featured a lavishly decorated beer tasting room known as the rathskeller. The rathskeller was a primary example of Art Deco Mexican/Hollywood style inspired by the movie industry of the 1920s and 1930s and was also influenced by regional sociocultural developments. The rathskeller featured two colorful murals by Jose Moya del Pino, an internationally recognized Spanish artist who had been influenced by Mexican muralists such as Diego Rivera. In addition to murals, the rathskeller’s furnishings included a large tiled bar and wrought iron chandeliers, as well as stained glass windows, wooden doors, painted ceiling beams, and intricate painted and molded plaster beam caps. The Aztec Brewing Company was in operation in San Diego until 1948 when it was sold to Altes Brewing Company, which closed its doors in the 1950s. -

California Supreme Court and San Diego County Appellate Court Briefs Collection MS-0078

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1d5nd8ch No online items California Supreme Court and San Diego County Appellate Court Briefs Collection MS-0078 Neil Medeiros, Jennie Labor, and Jennifer L. Martinez Special Collections & University Archives 12/05/2007 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA 92182-8050 [email protected] URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua California Supreme Court and San MS-0078 1 Diego County Appellate Court Briefs Collection MS-0078 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & University Archives Title: California Supreme Court and San Diego County Appellate Court Briefs Collection Identifier/Call Number: MS-0078 Physical Description: 56.25 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1891-1951 Date (bulk): 1900-1939 Language of Material: English . Scope and Contents The collection consists of California Supreme Court and San Diego Appellate Court documents from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The documents include filings of court transcripts, the opening briefs of appellants and respondents, as well as reply briefs. The court cases housed in the collection deal with a broad range of topics including bankruptcy, corporations, criminal law, divorce, drunk driving, labor, probate law, railroads, automobile accidents, mining and water. There are also important cases dealing with the cities of Escondido, Coronado, La Mesa, Lemon Grove, Pacific Beach, Spring Valley and National City. Some important San Diegans that appear in the court documents are Ed Fletcher, Katherine Tingley, John D. Spreckels, H.H. Timken, Julius Wangenheim, Cave J. Couts, Fred Sutherland, Henry Schumann-Heink, Samuel T. Black and F.T. Scripps. There are some cases of historical significance which illustrate the growth and development of San Diego in the early twentieth century. -

Savage, Standard Four and Mohawk : Tires of the Legendary Far West

CHAPTER 31 suggested citation: Medrano-Bigas, Pau. The Forgotten Years of Bibendum. Michelin’s American Period in Milltown: Design, Illustration and Advertising by Pioneer Tire Companies (1900-1930). Doctoral dissertation. University of Barcelona, 2015 [English translation, 2018]. SAVAGE, STANDARD FOUR AND MOHAWK : TIRES OF THE LEGENDARY FAR WEST In 1893 the Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented the essay The Significance of the Frontier in American History, which exposed his famous “Frontier Thesis,” at the World’s Columbian Exposition. It paid tribute to the expansion of lands to the West, a process that in his reasoning helped to develop a genuine American society that was open, free and just. This rationale won great acceptance and was assimilated as valid, although perhaps some facts were whitewashed and passed over in the process. The actual layout of this frontier was never defined, indeed, it constantly changed as settle- ments of populations originating from Europe continued spreading. From the snowy mountains to the desert, from California, Kansas and Nebraska to the Mexican-bordered Texas, the inaccessibility of unspoiled terrain and the culture clash with natives—often resolved in a violent way—characterized this diffuse area. 1. Railroads forging the way A fundamental fact in this expansion—once the Civil War ended—was the development of the nation- al railroad network, an authentic force that blazed its way through previously virgin places. The trans- atlantic union between the two oceanic coasts of the continent was completed in 1869 through the railways of the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, which were joined in 1883 by the Northern Pacif- ic and the Southern Pacific.