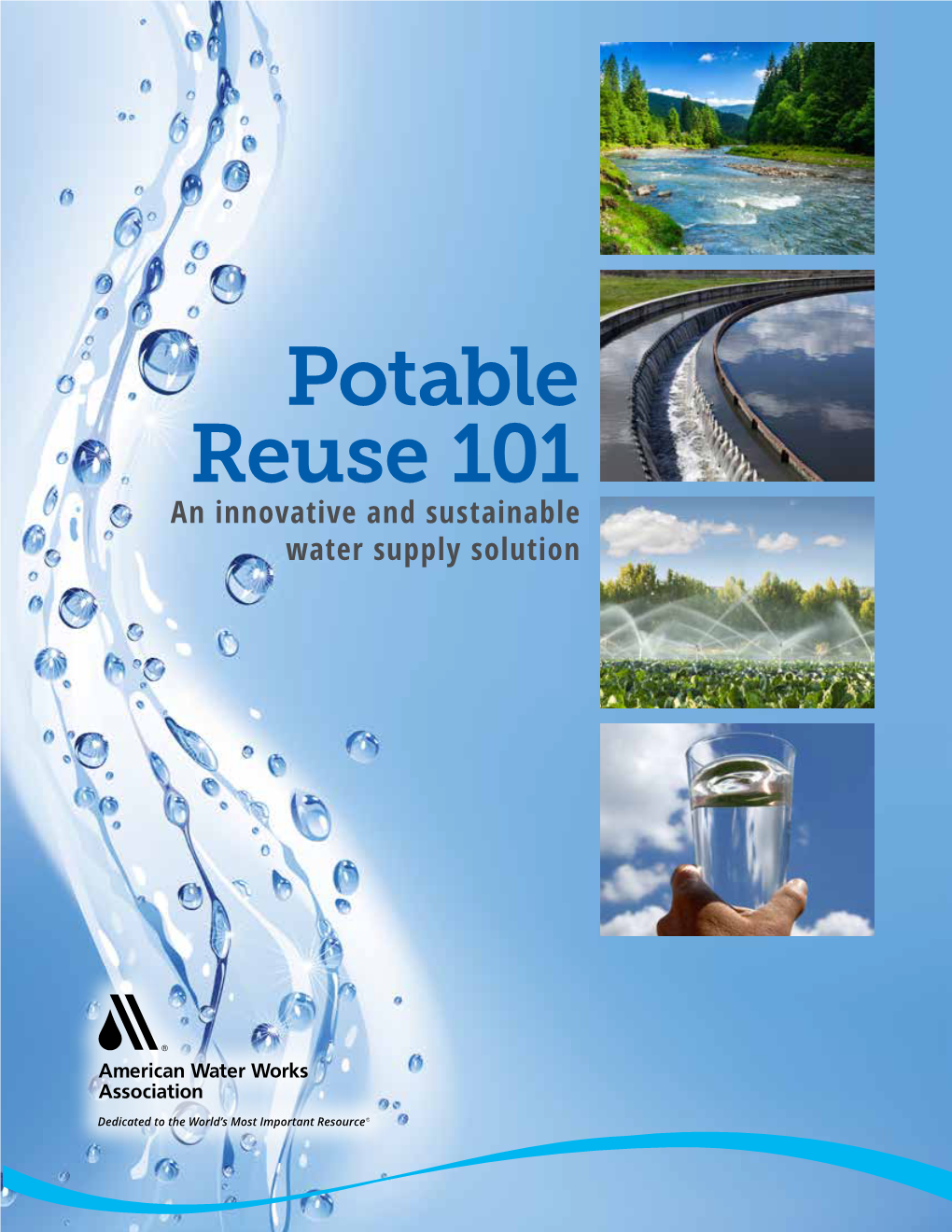

Potable Reuse 101: an Innovate and Sustainable Water Supply Solution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Guidance Manual

September 2002 RG-379 (Revised) Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Guidance Manual Water Supply Division printed on recycled paper TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Guidance Manual Prepared by Water Supply Division RG-379 (Revised) September 2002 Robert J. Huston, Chairman R. B. “Ralph” Marquez, Commissioner Kathleen Hartnett White, Commissioner Jeffrey A. Saitas, Executive Director Authorization to use or reproduce any original material contained in this publication—that is, not obtained from other sources—is freely granted. The commission would appreciate acknowledgment. Copies of this publication are available for public use through the Texas State Library, other state depository libraries, and the TCEQ Library, in compli- ance with state depository law. For more information on TCEQ publications call 512/239-0028 or visit our Web site at: www.tceq.state.tx.us/publications Published and distributed by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality PO Box 13087 Austin TX 78711-3087 The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality was formerly called the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission. The TCEQ is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. The agency does not allow discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, disability, age, sexual orientation or veteran status. In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, this document may be requested in alternate formats by contacting the TCEQ at 512/239-0028, Fax 239-4488, or 1-800-RELAY-TX (TDD), or by writing -

Reuse: a Safe and Effective Way to Save Water

SOUTH FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Water Reuse: A safe and effective way to save water ON THE INSIDE The demand for water is projected to increase over the long term in n Reclaimed water and reuse explained South Florida. Urban populations, agricultural operations and the environment depend on adequate water supplies. Fresh ground n Reuse success stories water and surface water will not be sufficient to satisfy all future n Reuse on a regional level demands. Meeting this growing thirst hinges on efforts to develop How water is reclaimed n alternative water sources. This brochure looks at one of the ways to n Purple pipes signify conserve Florida’s water resources — reclaiming water for reuse. reclaimed water Consider what happens to the water used inside the home. Once down the drain, this water is piped to the local wastewater treatment plant where it undergoes treatment to meet state standards for disposal. Historically, most of the water was disposed by injecting it deep underground or by discharging to surrounding waters or to the ocean. This is a wasteful way to treat such a valuable resource. More and more communities are finding that wastewater need not be wasted. They are reclaiming this water for irrigation of residential lots, golf courses, sports fields and orange groves; industrial cooling; car washing; fire protection; and Reclaimed water sign in Collier County groundwater recharge. Reuse is also beneficial to the environment. Success Stories During times of drought, reclaimed water •Pompano Beach – The city takes is a dependable source of water because wastewater being piped to the ocean, its availability is not dependent on rainfall. -

Redesign. Rethink. Reduce. Reuse. Go Beyond Recycling

REDESIGN. RETHINK. REDUCE. REUSE. GO BEYOND RECYCLING. WHAT IS ZERO WASTE? the entire lifecycle of products used within a facility. With TRUE, your facility can demonstrate to the world what you’re doing to minimize Zero waste is a philosophy that encourages the redesign of resource your waste output. life cycles so that all products are reused; a process that is very similar to the way that resources are reused in nature. Although recycling is HOW DOES CERTIFICATION WORK? the first step in the journey, achieving zero waste goes far beyond. By focusing on the larger picture, facilities and organizations can reap The TRUE Zero Waste certification program is an Assessor-based financial benefits while becoming more resource efficient. program that rates how well facilities perform in minimizing their non-hazardous, solid wastes and maximizing their efficient in the use According to the EPA, the average American generates 4.4 pounds of of resources. A TRUE project’s goal is to divert 90 percent or greater trash each day, and according to the World Bank, global solid waste overall diversion from the landfill, incineration (waste-to-energy) and generation is on pace to increase 70 percent by 2025. For every can of the environment for solid, non-hazardous wastes for the most recent garbage at the curb, for instance, there are 87 cans worth of materials 12 months. that come from extraction industries that manufacture natural resources into finished products—like timber, agricultural, mining and Certification is available for any physical facility and their operations, petroleum. This means that while recycling is important, it doesn’t including facilities owned by: companies, property managers, address the real problem. -

Reduce, Reuse and Recycle (The 3Rs) and Resource Efficiency As the Basis for Sustainable Waste Management

CSD-19 Learning Centre “Synergizing Resource Efficiency with Informal Sector towards Sustainable Waste Management” 9 May 2011, New York Co-organized by: UNCRD and UN HABITAT Reduce, Reuse and Recycle (the 3Rs) and Resource Efficiency as the basis for Sustainable Waste Management C. R. C. Mohanty UNCRD 3Rs offer an environmentally friendly alternatives to deal with growing generation of wastes and its related impact on human health, eco nomy and natural ecosystem Natural Resources First : Reduction Input Reduce waste, by-products, etc. Production (Manufacturing, Distribution, etc.) Second : Reuse Third : Material Recycling Use items repeatedly. Recycle items which cannot be reused as raw materials. Consumption Fourth : Thermal Recycling Recover heat from items which have no alternatives but incineration and which cannot Discarding be recycled materially. Treatment (Recycling, Incineration, etc.) Fifth : Proper Disposal Dispose of items which cannot be used by any means. (Source: Adapted from MoE-Japan) Landfill disposal Stages in Product Life Cycle • Extraction of natural resources • Processing of resources • Design of products and selection of inputs • Production of goods and services • Distribution • Consumption • Reuse of wastes from production or consumption • Recycling of wastes from consumption or production • Disposal of residual wastes Source: ADB, IGES, 2008 Resource efficiency refers to amount of resource (materials, energy, and water) consumed in producing a unit of product or services. It involves using smaller amount of physical -

The Role of Water Reclamation in Water Resources Management in the 21St Century

THE ROLE OF WATER RECLAMATION IN WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN THE 21ST CENTURY K. Esposito1*, R. Tsuchihashi2, J. Anderson1, J. Selstrom3 1*: Metcalf & Eddy, 60 East 42nd Street, 43rd Floor, New York, NY 10165 2: Metcalf & Eddy, 719 2nd Street, Suite 11, Davis, CA 95616 3: Metcalf & Eddy, 2751 Prosperity Ave Suite 200, Fairfax, VA 22031 ABSTRACT In recognition of the existing and impending stress to traditional water supply, water planners must look beyond structural developments and interbasin water transfers to secure supply into the future. In this process, it is becoming evident that various issues related to water must be integrated into a whole system approach, including water supply, water use, wastewater treatment, stormwater management, and management of surrounding water environment. In bringing disparate water assets together, alternatives to traditional water supply should arise. Integrated water resources management can provide a realistic framework for examining the feasibility of water reuse. This paper evaluates how water reuse can become a strategic alternative in water resources management. The key challenges that limit water reclamation as one of the key elements in integrated water resources management scheme are discussed, including limitations with typical centralized wastewater treatment systems and public health protection, particularly the implications of trace contaminants. The key considerations to address these challenges are presented including (1) selection of appropriate treatment processes and reuse applications, (2) scientific and engineering solutions to emerging concerns, (3) consideration for cost effective and sustainable system, and (4) public acceptance. Recent water reclamation projects are presented to illustrate the response of the engineering community to the challenges of making water reclamation and reuse a real and sustainable solution to water supply system management planning. -

Recommended Standards for Water Works 2007 Edition

Recommended Standards for Water Works 2007 Edition Policies for the Review and Approval of Plans and Specifications for Public Water Supplies A Report of the Water Supply Committee of the Great Lakes--Upper Mississippi River Board of State and Provincial Public Health and Environmental Managers MEMBER STATES AND PROVINCE Illinois Indiana Iowa Michigan Minnesota Missouri New York Ohio Ontario Pennsylvania Wisconsin Published by: Health Research Inc., Health Education Services Division, P.O. Box 7126, Albany, NY 12224 (518)439-7286 www.hes.org Copyright © 2007 by the Great Lakes - Upper Mississippi River Board of State and Provincial Public Health and Environmental Managers This book, or portions thereof, may be reproduced without permission from the author if proper credit is given. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD POLICY STATEMENT ON PRE-ENGINEERED WATER TREATMENT PLANTS POLICY STATEMENT ON AUTOMATED/UNATTENDED OPERATION OF SURFACE WATER TREATMENT PLANTS POLICY STATEMENT ON BAG AND CARTRIDGE FILTERS FOR PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES POLICY STATEMENT ON ULTRA VIOLET LIGHT FOR TREATMENT OF PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES POLICY STATEMENT ON INFRASTRUCTURE SECURITY FOR PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES POLICY STATEMENT ON ARSENIC REMOVAL INTERIM STANDARD - NITRATE REMOVAL USING SULFATE SELECTIVE ANION EXCHANGE RESIN INTERIM STANDARD - USE OF CHLORAMINE DISINFECTANT FOR PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES INTERIM STANDARD ON MEMBRANE TECHNOLOGIES FOR PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES PART 1 - SUBMISSION OF PLANS 1.0 GENERAL 1.1 ENGINEER’S REPORT 1.1.1 General Information 1.1.2 Extent of water works -

Designing out Waste: a Design Team Guide for Buildings

Uniclass A42: N462 CI/SfB (Ajp) (T6) Designing out Waste: A design team guide for buildings LESS WASTE, SHARPER DESIGN Halving Waste to Landfill “ Clients are making construction waste reduction a priority and design teams must respond. This stimulating guide to designing out construction waste clearly illustrates how design decisions can make a significant and positive difference, not only through reducing environmental impact but also making the most of resources. It’s a promising new opportunity for design teams, which I urge them to take up.” Sunand Prasad, RIBA President 1.0 Introduction 6 Contents 2.0 The case for action 8 2.1 Materials resource efficiency 10 2.2 Drivers for reducing waste 13 3.0 The five principles of Designing out Waste 14 3.1 Design for Reuse and Recovery 18 3.2 Design for Off Site Construction 20 3.3 Design for Materials Optimisation 23 3.4 Design for Waste Efficient Procurement 24 3.5 Design for Deconstruction and Flexibility 27 4.0 Project application of the five Designing out Waste principles 28 4.1 Client brief and designers’ appointments 31 4.2 RIBA Stage A/B: Appraisal and strategic brief 32 4.3 RIBA Stage C: Outline proposal 34 4.4 RIBA Stage D: Detailed proposals 38 4.5 RIBA Stage E: Technical design 40 5.0 Design review process 42 6.0 Suggested waste reduction initiatives 46 6.1 Design for Reuse and Recovery 48 6.2 Design for Off Site Construction 50 6.3 Design for Materials Optimisation 51 6.4 Design for Waste Efficient Procurement 52 6.5 Design for Deconstruction and Flexibility 53 Appendix A - The Construction Commitments: Halving Waste to Landfill 56 Appendix B - Drivers for reducing waste 57 Written by: Davis Langdon LLP ◀ Return to Contents This document provides information on the key principles that designers can use during the design process and how these Section 2.0 principles can be applied to projects to maximise opportunities Case for action – Presents to the construction industry the to Design out Waste. -

Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) (For Private Water and Health Regulated Public Water Supplies)

Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) (For Private Water and Health Regulated Public Water Supplies) What Is Dissolved Organic Carbon? Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is a general description of the organic material dissolved in water. Organic carbon occurs as the result of decomposition of plant or animal material. Organic carbon present in soil or water bodies may then dissolve when contacted by water. This dissolved organic carbon moves with both surface water and ground water. Acknowledgement: How Does Dissolved Organic Carbon Get Into Water? Organic material (including carbon) results from decomposition of plants or animals. This Fact Sheet is one of a Once this decomposed organic material contacts water it may partially dissolve. series developed by an Interagency Committee with representatives from How Does Dissolved Organic Carbon Affect My Health? Saskatchewan Ministry of DOC does not pose health risk itself but may become potentially harmful when in Health, Regional Health combination with other aspects of your water. When water with high DOC is Authorities, Saskatchewan chlorinated, harmful byproducts called trihalomethanes may be produced (see Watershed Authority, SaskH2O factsheet on trihalomethanes). Trihalomethanes may have long-term Saskatchewan Ministry of effects on health and they should be considered when chlorinating drinking water Environment, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, high in DOC. According to Health Canada, the benefits of chlorinating drinking Agriculture and Agri-Food water are much greater than the health risks associated with chlorination by- Canada – PFRA and Health products such as trihalomethanes Canada. DOC can interfere with the effectiveness of disinfection processes such as Responsibility for chlorination, ultraviolet and ozone sterilization. DOC can also promote the growth of interpretation of the content of microorganisms by providing a food source. -

Reduce Reuse Recycle Compost

Loyola is committed to waste reduction as part of our sustainability efforts. For more information on how you can help reduce waste on campus, please review this summary of available programs. Reduce • Eliminate Disposables – Get out of the habit of single-use-items. With a set of reusable products (cutlery, mug, water bottle, bag), you can cut down on plastics and save money. • Sustainable Purchasing - Take time to implement thoughtful purchasing practices to conserve resources and save the university money. o Life-Cycle Considerations – Before you bring something to campus, think about the full impact of its use. How much energy or water will it consume? Is there a way to recycle it when it’s not needed? o Third-Party Certified – Considering purchasing equipment or materials that meet reputable certifications. o Change Your Use – Always print double-sided. Avoid purchasing what you don’t need. Eliminate packaging materials where you can. • Green Move-In – Consider what you bring to campus. Don’t bring ‘one-off’ or delicate items that become someone’s problem to dispose of. For more information on Sustainable Purchasing use the ‘Guide to Green Purchasing at Loyola’ or talk to Loyola’s Purchasing Department. Reuse • In Your Department – Many times we have materials that others can use. Set up a re-use center to share office supplies, conference left-overs, or other common materials. • Think Green and Give – At the end of each school year, Loyola student donate tons of clothes and household goods through this program in the Residence Halls. LUC.edu/thinkgreenandgive • Biodiesel Program – Loyola ‘upcycles’ waste vegetable oil into vehicle fuel, biosoap, and other products. -

Turbidity Analysis for Oregon Public Water Systems Water Quality in Coast Range Drinking Water Source Areas June 2010

Report Turbidity Analysis for Oregon Public Water Systems Water Quality in Coast Range Drinking Water Source Areas June 2010 Last Updated: 06/29/10 By: Joshua Seeds DEQ 09-WQ-024 This report prepared by: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality 811 SW 6th Avenue Portland, OR 97204 1-800-452-4011 Contact: Joshua Seeds (503) 229-5081 [email protected] Turbidity Analysis for Oregon Public Water Systems Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................... i List of Figures .............................................................................................. iii List of Tables ............................................................................................... iiv List of Maps ................................................................................................. iiv Executive Summary ..................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 2 Applicable Turbidity Standards for Water Quality ............................................... 2 Public Water System Evaluations....................................................................... 3 Methods .......................................................................................................................... 5 Definitions of terms........................................................................................................ -

Publication No. 17: Ozone Treatment of Private Drinking Water Systems

PRIVATE DRINKING WATER IN CONNECTICUT Publication Date: April 2009 Publication No. 17: Ozone Treatment of Private Drinking Water Systems Effective Against: Pathogenic (disease-causing) organisms including bacteria and viruses, phenols (aromatic organic compounds), some color, taste and odor problems, iron, manganese, and turbidity. Not Effective Against: Large cysts and some other large organisms resulting from possible or probable sewage contamination, inorganic chemicals, and heavy metals. How Ozone (O3) Treatment Works Ozone is a chemical form of pure oxygen. Like chlorine, ozone is a strong oxidizing agent and is used in much the same way to kill disease-causing bacteria and viruses. It is effective against most amoebic cysts, and destroys bacteria and some aromatic organic compounds (such as phenols). Ozone may not kill large cysts and some other large organisms, so these should be eliminated by filtration or other procedures prior to ozone treatment. Ozone is effective in eliminating or controlling color, taste, and odor problems. It also oxidizes iron and manganese. Ozone treatment units are installed as point-of-use treatment systems. Raw water enters one opening and treated water emerges from another. Inside the treatment unit, ozone is produced by an electrical corona discharge or ultraviolet irradiation of dry air or oxygen. The ozone is mixed with the water whenever the water pump is running. Ozone generation units require a system to clean and remove the humidity from the air. For proper disinfection the water to be treated must have negligible color and turbidity levels. The system requires routine maintenance and an ozone treatment system can be very energy consumptive. -

Raw Water Irrigation System Master Plan

TOWN OF FIRESTONE RAW WATER IRRIGATION SYSTEM MASTER PLAN MARCH 2010 COLORADO CIVIL GROUP, INC. Raw Water Irrigation System Master Plan March 2010 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Goals ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope of Work ................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2.1 Existing Master Plan Evaluation ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2.2 Identifying Potential Areas for Raw Water Irrigation ............................................................................... 1 1.2.3 Irrigation Ditch Evaluation ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2.4 Hydraulic Analysis and Calculations ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.5 Raw Water System Modeling ................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.6 Raw Water Irrigation System Master