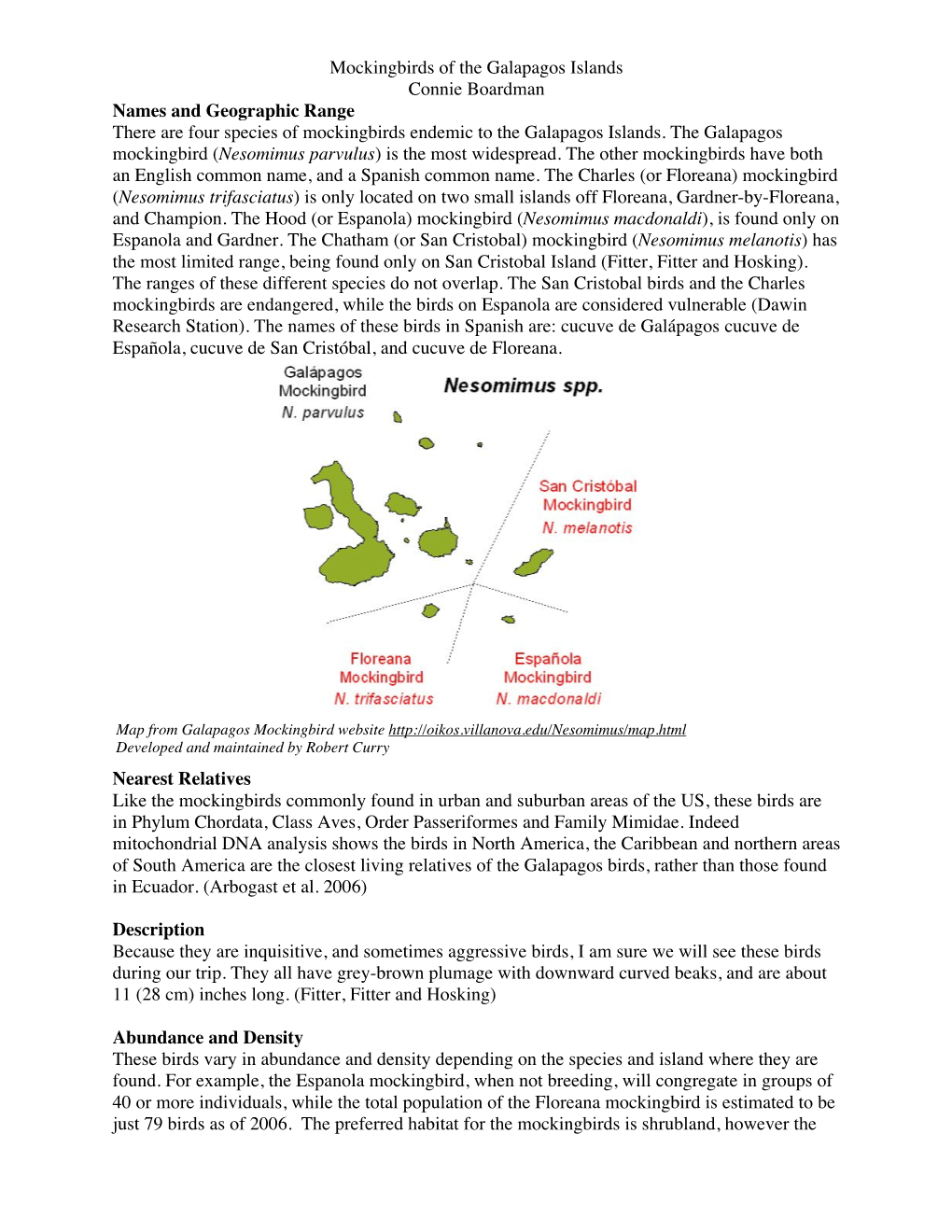

Mockingbirds of the Galapagos Islands Connie Boardman Names and Geographic Range There Are Four Species of Mockingbirds Endemic to the Galapagos Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unsustainable Food Systems Threaten Wild Crop and Dolphin Species

INTERNATIONAL PRESS RELEASE Embargoed until: 07:00 GMT (16:00 JST) 5 December 2017 Elaine Paterson, IUCN Media Relations, t+44 1223 331128, email [email protected] Goska Bonnaveira, IUCN Media Relations, m +41 792760185, email [email protected] [In Japan] Cheryl-Samantha MacSharry, IUCN Media Relations, t+44 1223 331128, email [email protected] Download photographs here Download summary statistics here Unsustainable food systems threaten wild crop and dolphin species Tokyo, Japan, 5 December 2017 (IUCN) – Species of wild rice, wheat and yam are threatened by overly intensive agricultural production and urban expansion, whilst poor fishing practices have caused steep declines in the Irrawaddy Dolphin and Finless Porpoise, according to the latest update of The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™. Today’s Red List update also reveals that a drying climate is pushing the Ringtail Possum to the brink of extinction. Three reptile species found only on an Australian island – the Christmas Island Whiptail-skink, the Blue- tailed Skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) and the Lister’s Gecko – have gone extinct, according to the update. But in New Zealand, conservation efforts have improved the situation for two species of Kiwi. “Healthy, species-rich ecosystems are fundamental to our ability to feed the world’s growing population and achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 – to end hunger by 2030,” says IUCN Director General Inger Andersen. “Wild crop species, for example, maintain genetic diversity of agricultural crops -

Of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds

B BIO VIEW Curator Notes From the Brink of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds In terms of conservation efforts, the Rio Grande Zoo is a rare breed in its own right, using its expertise to preserve and breed species whose numbers have dwindled to almost nothing both in the wild and in captivity. Recently, we took charge of a little over one-tenth of the entire world’s population of Socorro doves which have been officially extinct in the wild since 1978 and are now represented by only 100 genetically pure captive individuals that have been carefully preserved in European institutions. Of these 100 unique birds, 13 of them are now here at RGZ, making us the only holding facility in North America for this species and the beginning of this continent’s population for them. After spending a month in quarantine, the birds arrived safe and sound on November 18 from the Edinburgh and Paignton Zoos in England. Other doves have been kept in private aviaries in California, but have been hybridized with the closely related mourning dove, so are not genetically pure. History and Background Socorro doves were once common on Socorro Island, the largest of the four islands making up the Revillagigedo Archipelago in the East- ern Pacific ocean about 430 miles due west of Manzanillo, Mexico and 290 miles south of the tip of Baja, California. Although the doves were first described by 19th century American naturalist Andrew Jackson Grayson, virtually nothing is known about their breeding behavior in the wild. -

Floreana Island Galápagos, Ecuador

FLOREANA ISLAND GALÁPAGOS, ECUADOR FLOREANA ISLAND, GALÁPAGOS Floreana Mockingbird (Mimus trifasciatus) IUCN* Status: Endangered INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT THE FLOREANA MOCKINGBIRD: Locally extinct (extirpated) on Floreana Island The first mockingbird species described Inhabits and feeds on the pollen of the due to invasive rats and cats. It now survives by Charles Darwin during the voyage of Opuntia cactus, which has been impacted only on two invasive free oshore islets. the Beagle in 1835. by introduced grazers on Floreana. Floreana Island, Galápagos is the sixth largest island within the Galápagos archipelago and lies 1,000 km o the coast of Ecuador. In 1978, the Galápagos were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Galápagos National Park Directorate manages more than 98 percent of Floreana Island; an agricultural zone (230 ha) and the town of Puerto Valasco Ibarra (42 ha, 140 residents) fills the remaining 2 percent. Floreana Island is an Alliance for Zero Extinction site. WHY IS FLOREANA ISLAND IMPORTANT? Home to 54 threatened species, including species found nowhere else such as Floreana Mockingbird, Floreana Giant Tortoise, and the Floreana Racer. 13 seabird species nest on the island, 4 of which are found only in the Galápagos. FLOREANA ISLAND Galápagos Archipelago, Ecuador Home to 94 plant species found only in the Galápagos, six of which are found 1°17’51”S 90°26’03”W only on Floreana. THE PROBLEM Floreana Island is a paradise of its own; here a small human community of around 150 people live alongside a great, vibrant diversity of native plants and wildlife. Unfortunately, native flora and fauna are not alone in this paradise. -

Galapagos-Brochure.Pdf

THE GALÁPAGOS ARCHIPELAGO A PARADISE THREATENED BY INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES Island Conservation’s mission is to prevent extinctions by removing invasive species from islands. Our Galápagos Program prevents extinctions and improves human livelihoods by removing invasive alien species (IAS) from islands throughout the Galápagos Archipelago, develops local capacity, and supports our partners’ efforts to control IAS where eradication is not currently possible. WHY GALÁPAGOS? ISOLATION EVOLUTION EXTINCTION RESILIENCE Growing out of the ocean from The Galápagos’ remote location Of the 432 Galápagos species Invasive alien species (IAS) a volcanic hotspot 1,000 km means its islands were colonized assessed for the IUCN* Red are the leading threat to the off the coast of Ecuador, the by only a few species that List, 301 are threatened and Galápagos’ biodiversity and Galápagos Islands are home subsequently radiated into a many only occur in a fraction addressing IAS is a national to a fantastic array of 2,194 multitude of unique species. of their former range due to priority. Removing IAS will allow terrestrial plant and animal Darwin’s finches are a classic IAS. Four native species have threatened plant and animal species, 54% (1,187) of which example of this adaptive already gone extinct to date. populations the opportunity are endemic (found only in the radiation and inspired Darwin’s to recover, increasing their Galápagos). formulation of the theory of resilience to future threats, evolution. such as climate change. BUILDING PARTNERSHIPS AND CAPACITY TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE TAKING ACTION ISLAND CONSERVATION BOLD VISION Government institutions and local NGO’s Island Conservation (IC) is ideally The Galápagos National Park Directorate in the Galápagos are world leaders in IAS positioned to add value as a designer has a vision of an archipelago free of feral eradications from islands. -

Mimus Gilvus (Tropical Mockingbird) Family: Mimidae (Mockingbirds) Order: Passeriformes (Perching Birds) Class: Aves (Birds)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Mimus gilvus (Tropical Mockingbird) Family: Mimidae (Mockingbirds) Order: Passeriformes (Perching Birds) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Tropical mockingbird, Mimus gilvus. [http://asawright.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Tropical-Mockingbird.jpg, downloaded 16 November 2014] TRAITS. The tropical mockingbird is a songbird that can be identified by its ashy colour; grey body upperparts and white underparts. It has long legs, blackish wings with white bars and a long blackish tail with white edges. The juvenile is duller and browner than adults with a chest slightly spotted brown. The average length and weight of the bird is 23-25cm and 54g respectively (Hoyo Calduch et al., 2005). It has yellow eyes and a short, slender, slightly curved black bill. There is no apparent sexual dimorphism (Soberanes-González et al., 2010). It is the neotropical counterpart to the northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos), with its main difference being that the tropical mockingbird has less white in its wings and primaries (flight feathers). ECOLOGY. Mimus gilvus is found in open habitats ranging from savanna or farmland to human habitation. These birds are geographically distributed from southern Mexico to northern South America to coastal Eastern Brazil and the Southern Lesser Antilles, including Trinidad and Tobago (Coelho et al., 2011). The tropical mockingbird may have been introduced into Trinidad UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour and Panama, but these are now resident populations. It builds its cup-like nest in thick bushes or shrubbery with sticks and roots about 2-3m off the ground (Hoyo Calduch et al., 2005). -

Help Prevent the Extinction of the Floreana Mockingbird in Galapagos

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release: 15/11/2016 Help prevent the extinction of the Floreana mockingbird in Galapagos Galapagos Conservation Trust has launched a new appeal to save the critically endangered Floreana mockingbird. Only found on two tiny islets in the Galapagos Islands, this charismatic bird inspired Darwin’s theory of evolution, but is now on the verge of extinction. One of the most charming and fascinating species in Galapagos, the Floreana mockingbird is facing extinction with its population now only several hundred individuals. It is only found on two small islets near Floreana island, its original home, where it is thought to have been extinct since the late 1800s. With increasing threats to Galapagos, including more severe climatic events and invasive species, there is an urgent need to restore the mockingbird to the larger island of Floreana, in order to try and prevent its extinction. By supporting projects in Galapagos, the Galapagos Conservation Trust (GCT) has helped to protect several species, including the critically endangered mangrove finch and the endangered Galapagos giant tortoise. Returning the Floreana mockingbird home, however, is going to be one of the toughest challenges yet, and will form part of an ambitious island restoration project to eradicate invasive species and restore suitable habitat on the inhabited Floreana island. Jen Jones, Projects manager at GCT, commented, “With so many changes occurring in Galapagos, both human- and climate-driven, the fight to conserve endemic species is more important than ever. With plans progressing to restore Floreana island to its former glory, now is the time to turn the story of the Floreana mockingbird from one of uncertainty to one of optimism and our Floreana appeal aims to do just that.’ Luis Ortiz-Catedral, project leader on the 2016 Floreana mockingbird project, added, “Floreana island and all its endemic species must be conserved, not only because they are a unique piece of the magical diversity of the Galapagos Islands, but also because we can. -

Northern Mockingbird (Mimus Polyglottos) Deaver D

Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) Deaver D. Armstrong Goose Island State Park, TX 4/7/2006 © John Van Orman (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) The Northern Mockingbird’s incredible ability Distribution The Northern Mockingbird was first listed in to not only imitate but also remember up to 200 Michigan by Sager (1839). Barrows (1912) different “songs” is well known (Kroodsma called it a rare summer visitor to southern 2005). This remarkable bird uses songs of other Michigan and attributed at least some of the bird species and non-bird species and even reports to escaped caged birds. Wood (1951) copies sounds of mechanical devices like mentioned a total of seven nest records between telephones and sirens. Historically, the bird was 1910 and 1934, all in the SLP in counties which captured and caged for this very ability and have records in both Atlases and most other many early records in Michigan were historical accounts (Zimmerman and Van Tyne discounted as being attributed to escaped pets 1959, Payne 1983). Zimmerman and Van Tyne (Sprunt 1948, Barrows 1912). (1959) added records from Clare and Cheboygan Counties in the NLP. Payne (1983) The Northern Mockingbird regularly breeds as added 16 more counties to the list of those far north as the southern part of the eastern reporting Northern Mockingbirds in the provinces of Canada west to Ontario and then breeding season. Most of these newly added only casually north of a line drawn west across counties were in the NLP and the western UP. the U.S. from the southern half of Michigan. -

Gray Catbird, Northern Mockingbird and Brown Thrasher

Wildlife Note — 51 LDR0103 Gray Catbird, Northern Mockingbird and Brown Thrasher by Chuck Fergus Gray Catbird These three species are among the most vocal of our birds. All belong to Family Mimidae, the “mimic thrushes,” or “mimids,” and they often imitate the calls of other spe- cies, stringing these remembered vocalizations into long, variable songs. Family Mimidae has more than 30 spe- cies, which are found only in the New World, with most inhabiting the tropics. The mimids have long tails and short, rounded wings. The three species in the Northeast are solitary (living singly, in pairs and in family groups rather than in flocks), feed mainly on the ground and in shrubs, and generally eat insects in summer and fruits in winter. The sexes look alike. Adults are preyed upon by owls, hawks, foxes and house cats, and their nests may be raided by snakes, blue jays, crows, grackles, raccoons, opossums and squirrels. Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis) — The gray cat- bird is eight to nine inches long, smaller and more slen- der than a robin, an overall dark gray with a black cap Beetles, ants, caterpillars, and chestnut around the vent. Individuals often jerk their grasshoppers, crickets and other insects tails — up, down, and in circles. The species is named are common foodstuffs. Catbirds often forage on the for its mewling call, although catbirds also deliver other ground, using their bills to flick aside leaves and twigs sounds. They migrate between breeding grounds in the while searching for insects. eastern two-thirds of North America and wintering ar- Although not as talkative as the northern mocking- eas in the coastal Southeast and Central America. -

WILDLIFE in a CHANGING WORLD an Analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™

WILDLIFE IN A CHANGING WORLD An analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ Edited by Jean-Christophe Vié, Craig Hilton-Taylor and Simon N. Stuart coberta.indd 1 07/07/2009 9:02:47 WILDLIFE IN A CHANGING WORLD An analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ first_pages.indd I 13/07/2009 11:27:01 first_pages.indd II 13/07/2009 11:27:07 WILDLIFE IN A CHANGING WORLD An analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ Edited by Jean-Christophe Vié, Craig Hilton-Taylor and Simon N. Stuart first_pages.indd III 13/07/2009 11:27:07 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily refl ect those of IUCN. This publication has been made possible in part by funding from the French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Red List logo: © 2008 Copyright: © 2009 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Vié, J.-C., Hilton-Taylor, C. -

Breeding Season Diet of the Floreana Mockingbird (Mimus Trifasciatus), a Micro-Endemic Species from the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador

196 Notornis, 2014, Vol. 61: 196-199 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand Inc. Breeding season diet of the Floreana mockingbird (Mimus trifasciatus), a micro-endemic species from the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador LUIS ORTIZ-CATEDRAL Ecology and Conservation Group, Institute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Massey University, Private Bag 102-904, Auckland, New Zealand Abstract I conducted observations on the diet of the Floreana mockingbird (Mimus trifasciatus) during its breeding season in February and March 2011. The Floreana mockingbird is a critically endangered species restricted to Gardner and Champion Islets off the coast of Floreana Island, in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. During 11 days, 172 feeding bouts of adult and nestling mockingbirds were observed. The majority of feeding bouts of adults (31%; 19 feeding bouts) involved the consumption of nectar and pollen of Opuntia megasperma. Another important food item consisted of Lepidopteran caterpillars (27%; 17 feeding bouts). The majority of food items fed to nestlings consisted of Lepidopteran caterpillars (26%; 29 observations), followed by adult spiders (19%; 21 observations). The reintroduction of the species to its historical range on Floreana Island is currently being planned with an emphasis on the control or eradication of invasive cats and rats. To identify key areas for reintroduction, a study on the year-round diet of the species as well as availability and variability of food items is recommended. Nectar and pollen of Opuntia megasperma was an important dietary item for the species during its breeding season. This slow-growing plant species was widespread on the lowlands of Floreana Island but introduced grazers removed Opuntia from most of its range. -

Holocene Vertebrate Fossils from Isla Floreana, Galapagos

Holocene Vertebrate Fossils from Isla Floreana, Galapagos DAVID W. STEADMAN SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 413 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Like an Earthworm: Chalk-Browed Mockingbird (Mimus Saturninus) Kills and Eats a Juvenile Watersnake

470NOTA Ivan Sazima Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 15(3):470-471 setembro de 2007 Like an earthworm: Chalk-browed Mockingbird (Mimus saturninus) kills and eats a juvenile watersnake Ivan Sazima Departamento de Zoologia e Museu de História Natural, Caixa Postal 6109, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, CEP 13083‑970, Brasil. E‑mail: [email protected] Recebido em 20 de janeiro de 2007; aceito em 11 de maio de 2007. RESUMO: Como uma minhoca: o sabiá-do-campo (Mimus saturninus) mata e ingere uma cobra d’água juvenil. Diversas espécies de Passeriformes neotropicais apresam vertebrados, embora serpentes sejam presas raramente registradas. Apresento aqui um registro de sabiá‑do‑campo (Mimus saturninus) apresando uma cobra‑d’água juvenil. Uma vez que serpentes são presas perigosas, é aqui proposta a hipótese de que serpentes apresadas por Passeriformes sejam principalmente juvenis de espécies não‑venenosas e não‑constritoras. Também, sugiro que o apresamento de serpentes de pequeno porte e relativamente inofensivas representa uma alteração simples no comportamento de caça de Passeriformes que tenham o hábito de apresar minhocas e artrópodes alongados como lagartas e diplópodes. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Ofiofagia, comportamento predatório, presas alongadas. KEY-WORDS: Ophiophagy, predatory behaviour, elongate prey In a recent study of Neotropical passerine birds as vertebrate pecked at the mid body and even at the tail. After about 3 predators (Lopes et al. 2005) a surprising number of species min, the snake laid still on the ground and the bird began to (206) was found to prey on this animal type, although the swallow it. One juvenile individual from the group begged for number of stomachs with vertebrate remains was very low food and seemed to make attempts to steal the prey from the (0.3% out of 5,221 samples).