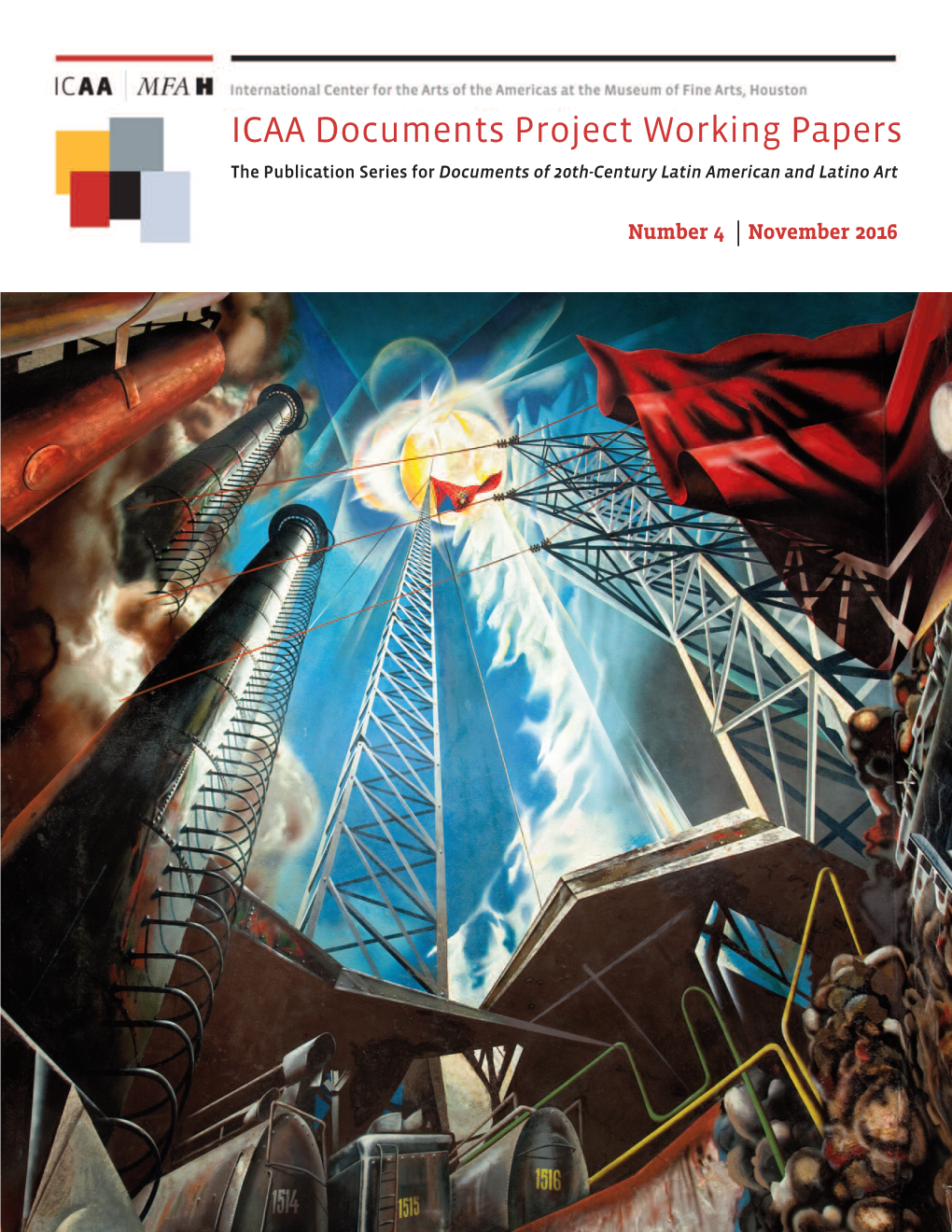

ICAA Documents Project Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHOTO Libraryinc. 305 EAST F O R T Y-S E V E N T H STREET • NEW YORK 17 • PL 2-4477 October 5> 1966 Miss Laura Gilpin P‘O

PHOTO LIBRARYinc. 305 EAST F O R T Y-S E V E N T H STREET • NEW YORK 17 • PL 2-4477 October 5> 1966 Miss Laura Gilpin P‘O. Box 1173 Santa Fe, New Mexico Dear Miss Gilpin: One of our clients is anxious to obtain as quickly as possible illustrative material, both in color and black and white, for a forthcoming book on Mexican art and architecture. I’m enclosing a list that you can use. as a guide; as you can see, our client Is most specific. Do you think you can mail us some of your photographs? We are looking forward to hearing from you. Very truly yours 1) Head of a coyote. Tequixquiac, Mexico State. About 10,000 B.C. 2) Small Seated Statue. Cairo de las Mesaas , Veracruz State. 300-800 A.D. Institute Hacional de Antropoligia e Historia, Mexico City. 3) Olmec Dwarf, and Mara Glyph. Cairo de las Mesaas, Veracruz State. 300-800 A D Institute Hacional de Antropologia e HLstorla, Mexico 6ity. 4) Head of a young Maya. Palenque, Chiapas State. Jgbout 683 A D Institute Hacional de Antropologia.....Mexico City 5) Facade of the Codz-Pop Building. Cabah, Tucutan State. 800-1200 A D 6) Temple of the Warriors. Chichen Itza, Yucatan State 800-1200 A D 7) Entrance to the Temple of the Warriors (see above for location) 8) Great Bail Court. Chichen Itza.... 9) Temple of Venus, with the Castillo in the background, Chichen Itza.... 10) Bearded ’Dancer*. Monte Alban, Oaxaca State. 200-100 B.C. 11) Zapotec Urn. -

Gallery of Mexican Art

V oices ofMerico /January • March, 1995 41 Gallery of Mexican Art n the early the 1930s, Carolina and Inés Amor decided to give Mexico City an indispensable tool for promoting the fine arts in whatI was, at that time, an unusual way. They created a space where artists not only showed their art, but could also sell directly to people who liked their work. It was a place which gave Mexico City a modem, cosmopolitan air, offering domestic and international collectors the work of Mexico's artistic vanguard. The Gallery of Mexican Art was founded in 1935 by Carolina Amor, who worked for the publicity department at the Palace of Fine Arts before opening the gallery. That job had allowed her to form close ties with the artists of the day and to learn about their needs. In an interview, "Carito" —as she was called by her friends— recalled a statement by the then director of the Palace of Fine Arts, dismissing young artists who did not follow prevailing trends: "Experimental theater is a diversion for a small minority, chamber music a product of the court and easel painting a decoration for the salons of the rich." At that point Carolina felt her work in that institution had come to an end, and she decided to resign. She decided to open a gallery, based on a broader vision, in the basement of her own house, which her father had used as his studio. At that time, the concept of the gallery per se did not exist. The only thing approaching it was Alberto Misrachi's bookstore, which had an The gallery has a beautiful patio. -

David Alfaro Siqueiros's Pivotal Endeavor

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-15-2016 David Alfaro Siqueiros’s Pivotal Endeavor: Realizing the “Manifiesto de New York” in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop of 1936 Emily Schlemowitz CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/68 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] David Alfaro Siqueiros’s Pivotal Endeavor: Realizing the “Manifiesto de New York” in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop of 1936 By Emily Schlemowitz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Hunter College of the City of New York 2016 Thesis Sponsor: __May 11, 2016______ Lynda Klich Date First Reader __May 11, 2016______ Harper Montgomery Date Second Reader Acknowledgments I wish to thank my advisor Lynda Klich, who has consistently expanded my thinking about this project and about the study of art history in general. This thesis began as a paper for her research methods class, taken my first semester of graduate school, and I am glad to round out my study at Hunter College with her guidance. Although I moved midway through the thesis process, she did not give up, and at every stage has generously offered her time, thoughts, criticisms, and encouragement. My writing and research has benefited immeasurably from the opportunity to work with her; she deserves a special thank you. -

David Alfaro Siqueiros Papers, 1921-1991, Bulk 1930-1936

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf9t1nb3n3 No online items Finding aid for the David Alfaro Siqueiros papers, 1921-1991, bulk 1930-1936 Annette Leddy Finding aid for the David Alfaro 960094 1 Siqueiros papers, 1921-1991, bulk 1930-1936 Descriptive Summary Title: David Alfaro Siqueiros papers Date (inclusive): 1920-1991 (bulk 1930-1936) Number: 960094 Creator/Collector: Siqueiros, David Alfaro Physical Description: 2.11 Linear Feet(6 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: A leading member of the Mexican muralist movement and a technical innovator of fresco and wall painting. The collection consists almost entirely of manuscripts, some in many drafts, others fragmentary, the bulk of which date from the mid-1930s, when Siqueiros traveled to Los Angeles, New York, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo, returning intermittently to Mexico City. A significant portion of the papers concerns Siqueiros's public disputes with Diego Rivera; there are manifestos against Rivera, eye-witness accounts of their public debate, and newspaper coverage of the controversy. There is also material regarding the murals América Tropical, Mexico Actual and Ejercicio Plastico, including one drawing and a few photographs. The Experimental Workshop in New York City is also documented. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in Spanish; Castilian and English Biographical/Historical Note David Alfaro Siqueiros was a leading member of the Mexican muralist movement and a technical innovator of fresco and wall painting. -

Documentary Essay by Dr

David Alfaro Siqueiros Self-Portrait with Mirror An essay by Dr. Irene Herner with the collaboration of Mónica Ruiz and Grecia Pérez. mary-anne martin | fine art 23 East 73rd Street New York, NY 10021 (212) 288-2213 www.mamfa.com Cover: David Alfaro Siqueiros Self-Portrait with Mirror 1937 pyroxylin on Bakelite 30 × 24 × ¼ in (76.2 × 61.0 × 0.6 cm) PROVENANCE Acquired directly from the artist by George Gershwin, NY, 1937 Estate of George Gershwin By descent to the present owner Photo: Grecia Pérez In 1936-37 New York, “Siqueiros’ workshop was a brave and dazzling new world, a calamitous introduction to a new way of thinking about art... Siqueiros generated a ‘torrential flow of ideas and new projects’ with a child’s eye for investigation and surprise.”1 I have written about and looked for Autorretrato con espejo since 1994. It was painted by Siqueiros in New York in his Siqueiros Experimental Workshop, signed and dated 1937. This is one of the key paintings in the process of the artist to construct kinetic dynamism in painting. It was out of sight, nobody knew who owned it, until now that it is on view at Mary-Anne Martin Fine Art, New York. The specialists thought it had been destroyed. In 1994, I rescued an archive photograph of it in black and white. Raquel Tibol published this photo on the cover of her 1996 anthology: Palabras de Siqueiros. David Alfaro Siqueiros, Self-Portrait What a great achievement it is to have found this original with Mirror, detail of the signature, 1937. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

INFORME CORRESPONDIENTE AL 2017 INFORME CORRESPONDIENTE AL 2017. Informe presentado por el Consejo Directivo Nacional de la Sociedad Mexicana de Autores de las Artes Plásticas, Sociedad De Gestión Colectiva De Interés Público, correspondiente al año 2017 ante la Asamblea General de Socios. Agradezco a todos los asistentes de su presencia en la actual asamblea informativa, dando a conocer todos los por menores realizados en el presente año, los cuales he de empezar a continuación: 1.- Se asistió a la reunión general de la Cisac, tratándose temas diversos según el orden del día presentado, plantando sobre el acercamiento con autores de los países: Guatemala, Panamá y Colombia para la conformación de Sociedades de Gestión en dichas naciones, donde estamos apoyando para su conformaciones y así tener mayor representatividad de nuestros socios, además de la recaudación de regalías. Les menciono que en primera instancia se desea abrir con el gremio de la música, pero una vez instaurada la infraestructura se piensa trabajar a otros gremios como la nuestra. Actualmente estamos en platicas de representación de nuestro repertorio en las sociedades de gestión ya instaladas en Costa Rica y Republica Dominicana donde existen pero para el gremio musical, considerando utilizar su plataforma e infraestructura para el cobro regalías en el aspecto de artes visuales en dichos países, tal como se piensa realizar en las naciones antes mencionadas una vez creadas. Dentro de la asamblea general anual de la CISAC, llevada a cabo en New York, logramos cerrar la firma de un convenio con la Sociedad de Autores y Artistas Visuales y de Imágenes de Creadores Franceses, con residencia en París, con ello cumpliendo con la meta de tener más ámbito de representación de los derechos autorales de nuestros socios nacionales. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

DANCING PLENA WITH THE BISHOP: AN ANALYSIS OF LORENZO HOMAR’S EL OBISPO DE PONCE LINOCUT PRINT By ANA D. RODRIGUEZ A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Ana D. Rodriguez I dedicate this effort to the younger and future generation of my family, hoping it serves as an example and inspiration ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I want to thank my family for their continuous support throughout my studies, my parents, Irma and Ramón, and my sisters, Gina, Cindy, Angie and Paula. I am especially grateful of my aunt Miriam Viruet for giving me shelter during the two weeks I spent collecting research material in Puerto Rico. I need to add into the family support group, my cousin Yahaira Sánchez for helping me collect text resources for my writing. From the University of Florida School of the Arts, I want to recognize and express my gratitude to Dr. Maya Stanfield-Mazzi, Chair of my Committee, for her patience, her guidance with my manuscript, and for keeping the faith in my work. To Dr. Efrain Barradas, for advising me to use the portfolio of Las Plenas from the Smathers’ Libraries Special Collections, for our conversations about Lorenzo Homar, and for being an inspiration. To Dr. Robin Poynor, for accepting to be a member of my committee and trusting my work. I also would like to acknowledge Dr. Margarita Vargas- Betancourt, Caribbean Basin Librarian at UF Smathers’ Library Latin American and Caribbean Collection (LACC), for all her continuous advice and support given during the making of this thesis. -

INFORME ANUAL CORRESPONDIENTE AL ÚLTIMO SEMESTRE DEL 2013 Y PRIMER SEMESTRE DE 2014

INFORME ANUAL CORRESPONDIENTE AL ÚLTIMO SEMESTRE DEL 2013 y PRIMER SEMESTRE DE 2014. Informe presentado por el Consejo Directivo Nacional de la Sociedad Mexicana de Autores de las Artes Plásticas, Sociedad De Gestión Colectiva De Interés Público, correspondiente al segundo semestre del 2013 y lo correspondiente al año 2014 ante la Asamblea General de Socios. Nuestra Sociedad de Gestión ha tenido varios resultados importantes y destacables con ello hemos demostrado que a pesar de las problemáticas presentadas en nuestro país se puede tener una Sociedad de Gestión como la nuestra. Sociedades homologas como Arte Gestión de Ecuador quienes han recurrido al cierre de la misma por situaciones económicas habla de la crisis vivida en nuestros días en Latinoamérica. Casos como Guatemala, Colombia, Honduras en especial Centro América, son a lo referido, donde les son imposibles abrir una representación como Somaap para representar a sus autores plásticos, ante esto damos las gracias a todos quienes han hecho posible la creación y existencia de nuestra Sociedad Autoral y a quienes la han presidido en el pasado enriqueciéndola y dándoles el impulso para que siga existiendo. Es destacable mencionar los logros obtenidos en las diferentes administraciones donde cada una han tenido sus dificultades y sus aciertos, algunas más o menos que otras pero a todas les debemos la razón de que estemos en estos momentos y sobre una estructura solida para afrontar los embates, dando como resultado la seguridad de la permanencia por algunos años más de nuestra querida Somaap. Por ello, es importante seguir trabajando en conjunto para lograr la consolidación de la misma y poder pensar en la Somaap por muchas décadas en nuestro país, como lo ha sido en otras Sociedades de Gestión. -

Museos Del Instituto Nacional De Bellas Artes Y Literatura, Abiertos Este 15 De Septiembre

Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Ciudad de México, a 13 de septiembre de 2019 Boletín núm. 1402 Museos del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, abiertos este 15 de septiembre • El 16 de septiembre permanecerán cerrados El próximo 15 de septiembre el público de la Ciudad de México y visitantes de otros lugares podrán disfrutar de una amplia oferta expositiva en los museos del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL). En el Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes se ofrece la exposición Pasajero 21, El Japón de Tablada, además de la oportunidad de visitar el Área de murales con importantes obras como: El hombre controlador del universo, Tercera Internacional, Carnaval de la vida mexicana (Diego Rivera), Tormento de Cuauhtémoc (David Alfaro Siqueiros), y otros más que el público podrá apreciar. Dentro del mismo recinto se encuentra el Museo Nacional de Arquitectura, ubicado en el tercer nivel del Palacio de Bellas. El Munarq ofrece a sus visitantes un recorrido por la historia del transporte colectivo más importante de México, con la muestra Metro 50 años. Ambos museos tendrán un horario de 10:00 a 15:00 horas. Por otro lado, el Museo Nacional de Arte (Munal) recibirá a los visitantes con la exposición ATL. Fuego, tierra y viento. Sublime sensación, muestra que pretende mostrar una secuencia fluida del trabajo de este artista, en la que se combina su fase de paisajista en asociación con su afición a la geología, la vulcanología y las expresiones del poder de la naturaleza. Voces de la tierra. Lenguas indígenas es una exposición que se conforma de obras pictóricas, escultóricas, impresas, fotográficas, textiles y dibujísticas que muestran la riqueza lingüística existente en el territorio mexicano. -

The Quixote Iconographic Museum

The Quixote Iconographic Museum There are moments when the fíats of ibis beach become the plateaus of La Mancha, and I see Don Quixote and Sancho riding their mounts as if they were real. I touch them, I hear them, they are here with us. Cervantes created them to be immortal. Oh, what a relief to read Quixote! To read it in a concentration camp, like the minute hand of the human dock, like the discovery of the ideals that justifii the madness of genius in calling for a government of reason. EULALIO FERRER BARGARES, FRANCE, JULY 16, 1939. ion t e has been riding for da the more than Tour cen- Foun tes n turies since Cervantes' rva pen immortalized him. Ce r rre H His exploits triumph over the barri- Fe lio la ers of language and are recognized Eu he the world over. Don Quixote, the f t o knight of sad countenance, comes tesy r alive in every time, in every gener- cou d te in ous man true to himself who risks r rep his own safety and takes the side of tos Pho the oppressed. El ingenioso Hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha (Don Quixote), trans- lated into practically all written lan- guages, almost obsessively critiqued and annotated, with a bibliography so large it is surpassed only by the Bible, is an image that goes beyond typeset and takes human form, a fig- ure recognizable through all time. Very few people are unaware of what Quixote looks like; no one would confuse him with anyone else. -

Tesis Para Obtener El Grado De Maestro En Imagen, Arte, Cultura Y

El muralismo mexicano como instrumento de significaciones de identidad visual. Caso de estudio La obra mural “México: Cultura y Sociedad que renace” de David Piñón Hernández “Seher One” Tesis para obtener el grado de Maestro en Imagen, Arte, Cultura y Sociedad Presenta Lic. Angel Flores Vega Director de tesis Mtro. Héctor C. Ponce de León Méndez Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, 2020. México. ii Para Lina, mi hija y a toda mi familia que me ha apoyado siempre. La Maestría en Imagen, Arte, Cultura y Sociedad (IMACS) está acreditada en el Programa Nacional de Posgrados de Calidad (PNPC) de Conacyt. Agradezco a Conacyt como patrocinador del proyecto realizado como tesis de maestría durante el programa de estudio de la Maestría en Imagen, Arte, Cultura y Sociedad. iii ÍNDICE Introducción…………………………………………………………………………………….1 Justificación…………………………………………………………………………………….9 Pregunta de investigación………………………………………………………………….10 Hipótesis……………………………………………………………………………………….10 Objetivos……………………………………………………………………………………….10 Metodología…………………………………………………………………………………...11 CAPÍTULO I / La imagen compleja………………………………………………………..18 I. Marco teórico desde la Comunicación visual………………………………………….…18 I.II. Conceptos del ciclo de la Comunicación visual………………………………………..22 1. Emisor / Creador visual…...………………………………………………………..24 2. Mensaje visual / Imagen……………………………………………………………25 3. Medio / Formas de exposición…………………………………………………….26 4. Tipo de imagen…………….………………………………………………………..28 5. Función de la imagen……….……………………………………………………...30 6. Contenido de la imagen…….……………………………………………………...32