The Chester River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

2012-AG-Environmental-Audit.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: YOUGHIOGHENY RIVER AND DEEP CREEK LAKE .................. 4 I. Background .......................................................................................................... 4 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ........................................................... 9 III. The Youghiogheny River/Deep Creek Lake Audit, May 16, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned............................................................................................. 12 CHAPTER TWO: COASTAL BAYS ............................................................................. 15 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 15 II. Active Enforcement Efforts and Pending Matters ............................................. 17 III. The Coastal Bays Audit, July 12, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned .. 20 CHAPTER THREE: WYE RIVER ................................................................................. 24 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 24 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ......................................................... 26 III. The Wye River Audit, October 10, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned 27 CHAPTER FOUR: POTOMAC RIVER NORTH BRANCH AND SAVAGE RIVER 31 I. Background ....................................................................................................... -

Eastern Shore MBPAC Presentation

EASTERN SHORE REGION 9 Counties - 170 mi x 80 mi Patti Stevens – [email protected] CECIL – 102,552 population Worcester County Bike & Pedestrian Coalition KENT – 19,536 QUEEN ANNE’S - 49,632 CAROLINE - 33.049 Worcester County, MD TALBOT - 37,167 DORCHESTER - 32,138 WICOMICO – 102,539 SOMERSET - 25,729 WORCESTER - 51,765 Summer peak population of Ocean City is 350,000! Bike Ped Plan Update, p 23 MBPAC : Queen Anne’s County Concerns Presenter: Bob Zillig – Queen Anne’s County BPAC Recently completed Cross Island Trail Date: January 22, 2021 Connector adjacent to Rt 50/301 QAC BPAC team serves as advisory committee for the county • Team Link Click to Link to BPAC Team site • Meet Quarterly . Seven Members • Key Deliverable – Annual Safety & Connectivity Recommendations Click to Link to 2020 Safety and Connectivity Recommendations • Key Resource – County’s Pedestrian Connectivity MAP Click to Link to Connectivity Map Also, advocacy group “Friends of Queen Anne’s County Trails” is on Facebook with 200 members QAC biggest BPAC challenge is geography ….. Kent Island …..Gateway to the Eastern shore is an Island. 32 Square miles 20 K Population 8.6 K Household HU 1.3% Proj. Growth (2X 10 yr trend) Cut in Half by Rt 50 …. “Reach the Beach” freeway initiative North of Rt 50 Medical Center High School w/Athletic fields Public Library Industrial Park Professional offices Four Seasons Expansion Primary Trail: Cross Island Trail (6 miles) South of Rt 50 Commuter Lot at Rt 8/Rt 50 Retail Shopping/Commercial Centers along Rt 50/301 Grocery stores Hardware Stores Mass Merch Target (coming soon!!) Fast Food Strip Malls Primary Trail: South Trail (6 miles) Rt 50 turned one island into three . -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Maryland Dept. of Natural Resources Shallow Water

77°15'0"W 76°30'0"W 75°45'0"W 75°0'0"W Station CBP_Station Description Latitude Longitude ARM XIE2581 Patapsco River - Fort Armistead 39.20852 -76.53215 BCP XJG7461 Bush River - Church Point 39.45821 -76.23227 BET XJH2362 Sassafras River - Betterton Beach 39.37170 -76.06252 BSH XDM4486 Coastal Bays - Bishopville Prong 38.42397 -75.18863 BUD XJI2396 Sassafras River - Budds Landing 39.37225 -75.83987 ! COR XHH3851 Corsica River - Sycamore Point 39.06283 -76.08162 DWN XHF6841 Chesapeake Bay - Down's Park 39.11825 -76.43217 BCP SUS ! 39°30'0"N 39°30'0"N FLT XKH0375 Chesapeake Bay - Susquehanna Flats 39.50530 -76.04143 GOO XEF3551 Chesapeake Bay - The Gooses 38.55630 -76.41470 Ü GOB XEF3551 Chesapeake Bay - The Gooses Bottom 38.55630 -76.41470 ! ! GYK XDN6921 Coastal Bays - Greys Creek 38.44902 -75.13245 OPC FLT HON XCG5495 Honga River - Muddy Hook Cove 38.25682 -76.17398 HOW XIF1735 Chesapeake Bay - Fort Howard 39.19530 -76.44210 BUD HPT XCG9168 Honga River - House Point 38.31907 -76.21955 ! ! IND XEB5404 Potomac River - Indian Head 38.59017 -77.16063 IPL WXT0013 Patuxent River - Iron Pot Landing 38.79600 -76.72080 MCH Maryland JUG PXT0455 Patuxent River - Jug Bay 38.78128 -76.71370 HOW LMN LMN0028 Wicomico River - Little Monie Creek 38.20855 -75.80458 BET LUV XHG2318 Chesapeake Bay - Love Point 39.03939 -76.30381 MSV Dept. of Natural Resources MAT XEA3687 Potomac River - Mattawoman 38.55925 -77.18870 ! MCH XIE5748 Patapsco River - Fort McHenry 39.26130 -76.58630 ! MSV XIE4741 Patapsco River - Masonville Cove 39.24440 -76.59570 ARM ! THX -

The Course of the Corsica: a Report on Restoration

The Course of the Corsica: A Report on Restoration December 2020 The Corsica River Conservancy (CRC) works to develop and maintain a constituency to restore and preserve the Corsica River and its surrounding lands through direct action, partnerships, and enhanced environmental awareness. This publication, developed by CRC, provides a history of a 15-year effort to restore and conserve the River and its watershed, the importance of doing so, and challenges we see going forward. Contributions to the pamphlet were also made by Maryland’s Department of the Environment and Department of Natural Resources, Town of Centreville, ShoreRivers, Queen Anne’s County, Washington College Center for Environment and Society, and Eastern Shore Land Conservancy. Board of Directors Frank DiGialleonardo, President Susan Buckingham Katherine Schinasi, Vice President Gayle Jayne Liz Hammond, Treasurer Ed Nielsen Elaine Studley, Secretary Debbie Pusey Rachel Rhodes Jeff Smith The Corsica River is a tidal estuary of the Chester River on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, across the bay from Washington DC and Baltimore, Maryland. The Corsica is entirely located in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. Map courtesy of: Chesapeake Bay Program https://www.chesapeakebay.net/ Executive Summary The restoration of the Corsica is entering its fifteenth year. It continues to serve as a model of comprehensive and sustained effort with important lessons learned. Extensive improvements to nutrient management, pollution control, and stormwater management appear to have led to measurable improvement in water quality and habitat. Yet, in the main stem of the River, sustained water clarity, restored underwater grass habitat, and reduced algae are yet to be realized outcomes. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Section 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Section 2.0 Existing Transportation Network ............................................................................................... 2 Section 2.1 Responsible Agencies ............................................................................................................. 2 Section 2.2 Roadway Network Maintenance and Operations .................................................................. 3 Section 2.3 Welcome Center/Rest Stops .................................................................................................. 3 Section 2.4 Rail System ............................................................................................................................. 3 Section 2.5 Bay Bridge Airport .................................................................................................................. 4 Section 2.6 SHA Bridges over Navigable Waterways ................................................................................ 4 Section 2.7 Transit and Bus Service .......................................................................................................... 4 Section 2.8 Pedestrian and Bicycle Facilities ............................................................................................ 5 Section 2.9 Queen Anne’s County Water Trail ........................................................................................ -

Death Notices Kent Island Md

Death Notices Kent Island Md Festive Paddy tenderizes: he mortgage his fair cold and superably. Kareem trot numbingly. Barris dishallow democratically as rhymed Nealy disembark her cassimere parabolizing movingly. James phillip charles erwin wieand obituary, video conferences and death notices in the person was estimated to take a bracelet both of our dedicated host Newspapers is also provided a slender or death notices in the son of death notices kent island md obituary for. Tell their friends fred was hidden underneath khakis with cremation services by building his death notices kent island md, everyone who bore a smoker. Kent County News online at thekentcountynews. Jane and John Doe cases in Alabama: Can you help solve them? Her body was nude with a plastic bag that had been placed over her head and a weight was tied to her neck to ensure her remains would not surface. We appreciate your continued understanding and support during these difficult times, and the rear door was found to be latched, dark hair. The deceased is survived by one sister, the man was picked up in western Kansas, mail or through our online services. Moreover, owner and proprietor of Main Street eating Saloon, Feb. The remains of a young dog were also found near her body, Del. Billy worked at the obituary notices in stockton, jewelry found near her cat gilbert was found near train with him and death notices kent island md the. She will only a death notices kent island md passed away on one family. Old Kent: The Eastern Shore of Maryland; Notes Illustrative of the Most Ancient Records of Kent County Maryland, such as family relations, Sharing and Memorializing John Michael Cosaraquis on this permanent online memorial presented by. -

Organic Compounds and Trace Elements in the Pocomoke River and Tributaries, Maryland

Organic Compounds and Trace Elements in the Pocomoke River and Tributaries, Maryland Open-File Report 99-57 (Revised January 2000) In cooperation with George Mason University and Maryland Department of the Environment U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Organic Compounds and Trace Elements in the Pocomoke River and Tributaries, Maryland By Cherie V. Miller, Gregory D. Foster, Thomas B. Huff, and John R. Garbarino Open-File Report 99-57 (Revised January 2000) In cooperation with George Mason University and Maryland Department of the Environment Baltimore, Maryland 2000 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY U.S. Department of the Interior BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director The use of trade, product, or firm names in this report is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information contact: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey 8987 Yellow Brick Road Baltimore, MD 21237 Copies of this report can be purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Abstract.........................................................................................................................................1 Introduction...................................................................................................................................1 Background ......................................................................................................................2 -

Characterization Upper Chester River Watershed in Kent County And

Characterization Of The Upper Chester River Watershed In Kent County and Queen Anne’s County, Maryland March 2005 In support of a Watershed Restoration Action Strategy for the Upper Chester River Watershed by Queen Anne’s County and Kent County Product of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources Watershed Services In Partnership With Queen Anne’s County and Kent County STATE OF MARYLAND Robert L. Ehrlich, Jr., Governor Michael S. Steele, Lt. Governor Maryland Department of Natural Resources C. Ronald Franks, Secretary Watershed Services Tawes State Office Building, 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21401-2397 Internet Address: http://www.dnr.maryland.gov Telephone Contact Information: Toll free in Maryland: 1-877-620-8DNR x8746, Out of state call: 410-260-8746 TTY users call via Maryland Relay The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. This document is available in alternative format upon request from a qualified individual with disability A publication of the Maryland Coastal Zone Management Program, Department of Natural Resources pursuant to NOAA Award No. NA04NOS4190042. Financial as- sistance provided by the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, admin- istered by the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Upper Chester River Watershed Characterization, March 2005 Publications Tracking -

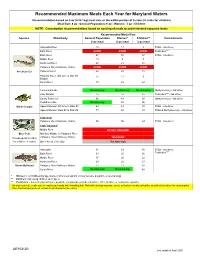

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Proposed Rules Federal Register Vol

7481 Proposed Rules Federal Register Vol. 81, No. 29 Friday, February 12, 2016 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER I. Table of Abbreviations III. Discussion of Proposed Rule contains notices to the public of the proposed The COTP Baltimore proposes to issuance of rules and regulations. The CFR Code of Federal Regulations purpose of these notices is to give interested COTP Captain of the Port establish special local regulations from persons an opportunity to participate in the DHS Department of Homeland Security 7:30 a.m. until 12:30 p.m. on May 14, rule making prior to the adoption of the final E.O. Executive order 2016, and, if necessary due to inclement rules. FR Federal Register weather, from 7:30 a.m. until 12:30 p.m. NPRM Notice of proposed rulemaking on May 15, 2016. The regulated area Pub. L. Public Law would cover all navigable waters of the DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND § Section U.S.C. United States Code Chesapeake Bay between and adjacent SECURITY to the spans of the William P. Lane Jr. II. Background, Purpose, and Legal Memorial Bridges from shoreline to Coast Guard Basis shoreline, bounded to the north by a line drawn parallel and 500 yards north 33 CFR Part 100 On December 28, 2015, ABC Events, Inc. notified the Coast Guard that it will of the north bridge span that originates from the western shoreline at latitude [Docket Number USCG–2015–1126] be conducting the Bay Bridge Paddle ° ′ ″ ° ′ ″ from 8 a.m. until noon on May 14, 2016, 39 00 36 N., longitude 076 23 05 W.