Introduction Martine Robbeets and Alexander Savelyev The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transeurasian Verbal Morphology in a Comparative Perspective: Genealogy, Contact, Chance

Turcologica 78 Transeurasian verbal morphology in a comparative perspective: genealogy, contact, chance Bearbeitet von Lars Johanson, Martine I Robbeets 1. Auflage 2010. Taschenbuch. V, 180 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 447 05914 5 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 360 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Literatur, Sprache > Sprachwissenschaften Allgemein > Grammatik, Syntax, Morphologie Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Transeurasian verbal morphology in a comparative perspective: genealogy, contact, chance Edited by Lars Johanson and Martine Robbeets 2010 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 0177-4743 ISBN 978-3-447-05914-5 Contents Lars Johanson & Martine Robbeets....................................... .................................... Introduction............................................................................................................................ 1 Lars Johanson...... ...... The high and low spirits of Transeurasian language studies .............................................. 7 Bernard Comrie.......................................... .................................................................. The role of verbal morphology -

Robbeets, Martine 2017. Japanese, Korean and the Transeurasian Languages

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309763268 Robbeets, Martine 2017. Japanese, Korean and the Transeurasian languages. In: Hickey, Raymond (ed.) The Cambridge handbook... Chapter · November 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 26 1 author: Martine Robbeets Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History 37 PUBLICATIONS 21 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Martine Robbeets on 16 November 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/8902253/WORKINGFOLDER/HICY/9781107051614C22.3D 586 [586–626] 9.11.2016 5:30PM 22 The Transeurasian Languages Martine Robbeets 22.1 Introduction The present contribution is concerned with the areal concentration of a number of linguistic features in the Transeurasian languages and its histor- ical motivation. The label ‘Transeurasian’ was coined by Johanson and Robbeets (2010: 1–2) with reference to a large group of geographically adjacent languages, traditionally known as ‘Altaic’, that share a significant number of linguistic properties and include up to five different linguistic families: Japonic, Koreanic, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic. The question whether all similarities between the Transeurasian languages should be accounted for by language contact or whether some are the residue of a common ancestor is one of the most debated issues of historical compara- tive linguistics (see Robbeets 2005 for an overview of the debate). Since the term ‘linguistic area’ implies that the shared properties are the result of borrowing, I will refrain from aprioriattaching it to the Transeurasian region and rely on the concept of ‘areality’ instead, that is, the geographical concentration of linguistic features, independent of how these features developed historically. -

Austronesian Influence Andtranseurasian Ancestry in Japanese

Language Dynamics and Change 7 (2017) 210–251 brill.com/ldc Austronesian influence and Transeurasian ancestry in Japanese A case of farming/language dispersal Martine Robbeets Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History [email protected] Abstract In this paper, I propose a hypothesis reconciling Austronesian influence and Trans- eurasian ancestry in the Japanese language, explaining the spread of the Japanic lan- guages through farming dispersal.To this end, I identify the original speech community of the Transeurasian language family as the Neolithic Xinglongwa culture situated in the West Liao River Basin in the sixth millennium bc. I argue that the separation of the Japanic branch from the other Transeurasian languages and its spread to the Japanese Islands can be understood as occurring in connection with the dispersal of millet agri- culture and its subsequent integration with rice agriculture. I further suggest that a prehistorical layer of borrowings related to rice agriculture entered Japanic from a sis- ter language of proto-Austronesian, at a time when both language families were still situated in the Shandong-Liaodong interaction sphere. Keywords Transeurasian – Austronesian – Japanese – farming/language dispersal hypothesis – borrowing – inheritance 1 Introduction The Japanese language displays remarkable similarities with the Transeur- asian—traditionally called “Altaic”—languages as well as with the Austrone- sian languages. This fact has given rise to a certain polarization in classification attempts between scholars who try to relate Japanese to the Transeurasian lan- © martine robbeets, 2017 | doi: 10.1163/22105832-00702005 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc license at the time of publication. -

Transeurasian: Can Verbal Morphology End the Controversy? 1

Transeurasian: Can verbal morphology end the controversy? Martine Robbeets 1 Which end of the controversy? Recently, both supporters and critics of the hypothesis that the Transeurasian languages are affiliated have claimed to have ended the controversy. Whereas the authors of “Etymolo- gical dictionary of the Altaic languages” express their hope (Starostin et al. 2003: 7) “that this publication will bring an end to this discussion”, Vovin’s (2005) review, subtitled “The end of the Altaic controversy” claims to put an end to it in the opposite way, while Dybo & Starostin (2008) return to the other end of the controversy in a rebuttal of Vovin’s critique, titled “The end of the Vovin controversy”. In reality the issue seems to be more controversial than it has ever been. And yet, supporters and critics seem to agree on at least one point, namely that shared morphology could substantially help unravel the question. Vovin (2005: 73) begins his critique with the postulation that “The best way … is to prove a suggested genetic relationship on the basis of paradigmatic morphology …”. Dybo & Starostin (2008: 125) agree that “… regular paradigmatic correspondences in morphology are necessarily indicative of genetic relationship”. The present paper examines the role of shared verbal morphology in the affiliation question of the Transeurasian languages. The term “Transeurasian” is used in reference to Japanese, Korean, the Tungusic languages, the Mongolic languages and the Turkic languages. In the first section it is explained why, unlike in Indo-European, it is unreasonable to expect the reconstruction of paradigmatic verbal morphology and why diathesis is such a fruitful category to begin with. -

Altaic Languages

Altaic Languages Masaryk University Press Reviewed by Ivo T. Budil Václav Blažek in collaboration with Michal Schwarz and Ondřej Srba Altaic Languages History of research, survey, classification and a sketch of comparative grammar Masaryk University Press Brno 2019 Publication financed by the grant No. GA15-12215S of the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR) © 2019 Masaryk University Press ISBN 978-80-210-9321-8 ISBN 978-80-210-9322-5 (online : pdf) https://doi.org/10.5817/CZ.MUNI.M210-9322-2019 5 Analytical Contents 0. Preface .................................................................. 9 1. History of recognition of the Altaic languages ............................... 15 1.1. History of descriptive and comparative research of the Turkic languages ..........15 1.1.1. Beginning of description of the Turkic languages . .15 1.1.2. The beginning of Turkic comparative studies ...........................21 1.1.3. Old Turkic language and script – discovery and development of research .....22 1.1.4. Turkic etymological dictionaries .....................................23 1.1.5. Turkic comparative grammars .......................................24 1.1.6. Syntheses of grammatical descriptions of the Turkic languages .............25 1.2. History of descriptive and comparative research of the Mongolic languages .......28 1.2.0. Bibliographic survey of Mongolic linguistics ...........................28 1.2.1. Beginning of description of the Mongolic languages .....................28 1.2.2. Standard Mongolic grammars and dictionaries ..........................31 1.2.3. Mongolic comparative and etymological dictionaries .....................32 1.2.4. Mongolic comparative grammars and grammatical syntheses...............33 1.3. History of descriptive and comparative research of the Tungusic languages ........33 1.3.0. Bibliographic survey of the Tungusic linguistics.........................33 1.3.1. Beginning of description of the Tungusic languages ......................34 1.3.2. -

WHERE and WHEN? Martine Robbeets a Centuries Old

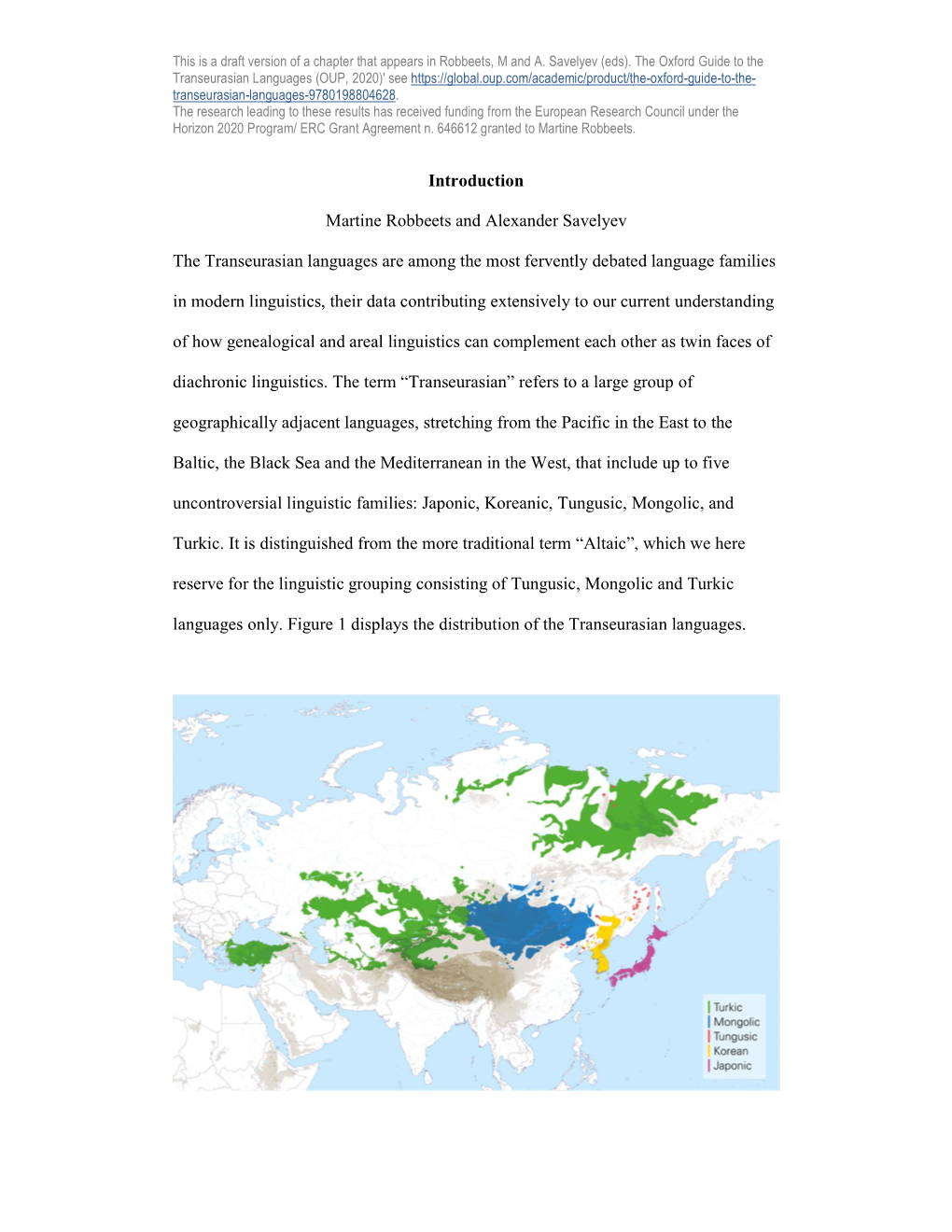

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by MPG.PuRe Man In India, 97 (1): 19–46 © Serials Publications PROTO-TRANS-EURASIAN: WHERE AND WHEN? Martine Robbeets A centuries old controversy Explaining linguistic diversity in East Asia is among the most important challenges of ethno-linguistics. Especially controversial is the question about the ultimate unity or diversity of the Trans-Eurasian languages. The term “Trans- Eurasian” was coined by Lars Johanson and myself to refer to a large group of geographically adjacent languages, stretching from the Pacific in the East to the Baltic and the Mediterranean in the West (Johanson & Robbeets 2010: 1-2). As illustrated in Figure 1, this grouping includes up to five different linguistic families: Japonic, Koreanic, Tungusic, Mongolic, and Turkic. I distinguish “Trans-Eurasian” from the more traditional term “Altaic”, which can be reserved for the linguistic grouping consisting of Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic languages only. The question of whether these five families descend from a single common ancestor has been the topic of a longstanding debate, for an overview of which I refer to Robbeets (2005: 18-29). The main issue is whether all shared forms are generated by horizontal transmission (i.e. borrowing), or whether some of them are residues of vertical transmission (i.e. inheritance). In Robbeets (2005), I showed that the majority of etymologies proposed in support of a genealogical relationship between the Trans-Eurasian languages are indeed questionable. Nevertheless, I reached a core of reliable etymologies that enables us to classify Trans-Eurasian as a valid genealogical grouping. -

Transeurasian Verbal Morphology in a Comparative Perspective: Genealogy, Contact, Chance

Turcologica 78 Transeurasian verbal morphology in a comparative perspective: genealogy, contact, chance Bearbeitet von Lars Johanson, Martine I Robbeets 1. Auflage 2010. Taschenbuch. V, 180 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 447 05914 5 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 360 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Literatur, Sprache > Sprachwissenschaften Allgemein > Grammatik, Syntax, Morphologie Zu Leseprobe schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Transeurasian verbal morphology in a comparative perspective: genealogy, contact, chance Edited by Lars Johanson and Martine Robbeets 2010 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 0177-4743 ISBN 978-3-447-05914-5 Contents Lars Johanson & Martine Robbeets....................................... .................................... Introduction............................................................................................................................ 1 Lars Johanson...... ...... The high and low spirits of Transeurasian language studies .............................................. 7 Bernard Comrie.......................................... .................................................................. The role of verbal morphology -

The Causative-Passive in the Trans-Eurasian Languages

The causative-passive in the Trans-Eurasian languages Martine Robbeets Robbeets, Martine 2007. The causative-passive in the Trans-Eurasian languages. Turkic Languages. 11, xx-xx. The affiliation question of the Trans-Eurasian languages is among the most controversial issues of historical linguistics. A major difficulty is the distinction between genetic reten- tion and code-copying. The present article studies two causative-passive markers relating Japanese to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic. The decision to concentrate on dia- thetical suffixes is motivated by the cross-linguistic observation that the positions closest to the verbal stem are resistant to code-copying. As a consequence of their relative conser- vativism, the causative-passive suffixes compared in this study are no longer productive: they have petrified into verb stems. In spite of the ongoing lexicalization, the suffixes can be reconstructed for the individual languages on the basis of diagrammatic iconicity. In the comparative part of this study, a common causative-passive suffix pTE *-ti- and an ancil- lar auxiliary pTE *ki- ‘make, do’ that grammaticalized into a marker of causativity, are re- constructed. The shared properties are assessed in terms of form, function, combinational behavior and systemic organization. The article concludes that it is more logical to attrib- ute the causative-passive etymologies to genetic retention than to motivate them by code- copying. Martine Robbeets, Seminar für Orientkunde, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, DE- 55099 Mainz, Germany. 1. Introduction Trans-Eurasian is used in reference to a vast zone of geographically adjacent lan- guages stretching from the Pacific in the East to the Black Sea in the West. -

Austronesian Influence Andtranseurasian Ancestry In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MPG.PuRe Language Dynamics and Change 7 (2017) 210–251 brill.com/ldc Austronesian influence and Transeurasian ancestry in Japanese A case of farming/language dispersal Martine Robbeets Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History [email protected] Abstract In this paper, I propose a hypothesis reconciling Austronesian influence and Trans- eurasian ancestry in the Japanese language, explaining the spread of the Japanic lan- guages through farming dispersal.To this end, I identify the original speech community of the Transeurasian language family as the Neolithic Xinglongwa culture situated in the West Liao River Basin in the sixth millennium bc. I argue that the separation of the Japanic branch from the other Transeurasian languages and its spread to the Japanese Islands can be understood as occurring in connection with the dispersal of millet agri- culture and its subsequent integration with rice agriculture. I further suggest that a prehistorical layer of borrowings related to rice agriculture entered Japanic from a sis- ter language of proto-Austronesian, at a time when both language families were still situated in the Shandong-Liaodong interaction sphere. Keywords Transeurasian – Austronesian – Japanese – farming/language dispersal hypothesis – borrowing – inheritance 1 Introduction The Japanese language displays remarkable similarities with the Transeur- asian—traditionally called “Altaic”—languages as well as with the Austrone- sian languages. This fact has given rise to a certain polarization in classification attempts between scholars who try to relate Japanese to the Transeurasian lan- © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2017 | doi: 10.1163/22105832-00702005 austronesian influence and transeurasian ancestry in japanese 211 guages on the one hand (e.g., Miller, 1971; Vovin, 1994; Starostin et al., 2003; Robbeets, 2005) and others who try to relate it to the Austronesian languages on the other hand (e.g., Kawamoto, 1985; Benedict, 1990). -

Chapter 43 the Homelands of the Individual Transeurasian Proto

This is a draft version of a chapter that appears in Robbeets, M and A. Savelyev (eds). The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages (OUP, 2020)' see https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-oxford-guide-to-the- transeurasian-languages-9780198804628. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the Horizon 2020 Program/ ERC Grant Agreement n. 646612 granted to Martine Robbeets. Chapter 43 The homelands of the individual Transeurasian proto-languages Martine Robbeets, Juha Janhunen, Alexander Savelyev and Evgeniya Korovina Abstract This chapter is an attempt to identify the individual homelands of the five families making up the Transeurasian grouping, i.e. the Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Koreanic and Japonic families. Combining various linguistic methods and principles such as the diversity hotspot principle, phylolinguistics, cultural reconstruction and contact linguistics, we try to determine the original location and time depth of the families under discussion. We further propose that the individual speech communities were originally familiar with millet agriculture, while terms for pastoralism or wet- rice agriculture entered their vocabularies only at a later stage. Keywords: Japonic, Koreanic, Tungusic, Mongolic, Turkic, Transeurasian, homeland, time depth, agriculture, cultural reconstruction, contact linguistics 43.1 Introduction The aim of this chapter is to estimate the location and time depth of the individual families that make up the Transeurasian grouping and to suggest evidence for the presence of agricultural vocabulary in each of the proto-languages. In the present context, farming or agriculture is understood in its restricted sense of economic dependence on the cultivation of crops and does not necessarily include the raising of animals as livestock. -

New Trends in European Studies on the Altaic Problem

Anna Dybo Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences; [email protected] New trends in European studies on the Altaic problem The paper discusses several general problems of present-day historical Altaistics, taking as a reference point the critical evaluation of two large monographs by Martine Robbeets — one on the Altaic origins of the Japanese language (Robbeets, Martine. 2005. Is Japanese related to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic? Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz) and another on the evi- dence that comparative verbal morphology provides to validate the Altaic hypothesis (Rob- beets, Martine. 2015. Diachrony of verb morphology: Japanese and the Transeurasian languages. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter). Along with the analysis of the main methodological principles and some specific etymological decisions taken by the author, the paper also focuses on the critical discussion of certain assumptions that may be seen as typical of “anti-Altaic” re- searchers. Keywords: Altaic languages, historical Turkology, verbal morphology, long-range compari- son, history of the Japanese language, etymology. After the Etymological Dictionary of Altaic Languages (EDAL) came out in 2003, accompanied by both positive (Blažek 2005; Miller 2004) and sharply negative (Vovin 2005; Stachowski 2005; Norman 2009; Georg 2004) reviews, it seems logical that the next step, instead of a Sturm und Drang-style gathering of additional material to confirm the updated reconstruction, should rather be a verification and cleanup of the already accomplished work. The author of these lines remains fully convinced (in fact, has always been convinced) that the first collection of Altaic etymologies with claims to a certain degree of completeness, published by S. Starostin, A. -

About Millets and Beans, Words and Genes

Evolutionary Human Sciences (2020), 2, e33, page 1 of 13 doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.33 EDITORIAL About millets and beans, words and genes Martine Robbeets1* and Chuan-Chao Wang2 1Eurasia3angle Research group, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany and 2Department of Anthropology and Ethnology, Institute of Anthropology, National Institute for Data Science in Health and Medicine, and School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this special collection, we address the origin and dispersal of the Transeurasian languages, i.e. Japonic, Koreanic, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic, from an interdisciplinary perspective. Our key objective is to effectively synthesize linguistic, archaeological and genetic evidence in a single approach, for which we use the term ‘triangulation’. The 10 articles collected in this volume contribute to the question of whether and to what extent the early spread of Transeurasian languages was driven by agriculture in general, and by economic reliance on millet cultivation in particular. Key words: Transeurasian; triangulation; genetics; linguistics; archaeology; Neolithic; millet agriculture Media summary: In this special collection, we address the origin and dispersal of the Transeurasian languages, by synthesizing linguistic, archaeological and genetic evidence in a single approach. The origin and dispersal of the Transeurasian languages is among the most fervently disputed issues in historical comparative linguistics. In this special collection, we address this topic from an interdiscip- linary perspective. Our key objective is to effectively synthesize linguistic, archaeological and genetic evidence in a single approach, for which Bellwood (2002:23–25) introduced the term ‘triangulation’, generalizing Kirch and Green (2001)’s earlier application of the term to Polynesian language and archaeology.