Peaks of the Sissu Nala Basin,· Lahul Himaijaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photographic Archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus

Photographic archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Photographic archives in Paris and London. European bulletin of Himalayan research, University of Cambridge ; Südasien-Institut (Heidelberg, Allemagne)., 1999, Special double issue on photography dedicated to Corneille Jest, pp.103-106. hal-00586763 HAL Id: hal-00586763 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00586763 Submitted on 10 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EBHR 15- 16. 1998- 1999 PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES IN PARIS AND epal among the Limbu. Rai. Chetri. Sherpa, Bhotiya and Sunuwar. LONDO ' Both these collections encompa'\s pictures of land flY PA CALE DOLL FUSS scapes. architecture. techniques. agriculture. herding, lrade, feslivals. shaman practices. rites or passage. etc. In addition to these major collecti ons. once can find I. PUOTOGRAPfIIC ARCIUVES IN PARIS 350 photographs taken in 1965 by Jaeques Millot. (director of the RCP epal) in the Kathmandu Valley. Photographic Library ("Phototheque"), Musee de approx. 110 photographs (c. 1966-67) by Mireille Helf /'lIommc. fer. related primari Iy to musicians caSles, 45 photo 1'1. du Trocadero. Paris 750 16. graphs (1967-68) by Marc Gaborieau. -

Mountain Biking- Manali to Leh (Ladakh) Across the Roof Top of the World

Kedar Gogte 112/3, Amrut Apartment, Prabhat Road, Pune-411004 Maharashtra, India 9850896145/020-25430505 MOUNTAIN BIKING- MANALI TO LEH (LADAKH) ACROSS THE ROOF TOP OF THE WORLD This scenic and picturesque landscape of Ladakh is among the most breathtaking in the World. Your bike tour starts among the lush green and alpine meadows of the Kullu valley and then crosses the Main Himalayan Ranges to the fabled lands of Lahoul and Ladakh. Over the next few days you will ride through breathtaking high altitude desert plateaus; High Mountain passes; remote mountain villages and visit splendid Buddhist monasteries. You will see camping grounds of Tibetan nomads, the Changpas and migrating herds of Kiangs (wild ass). As a climax to the entire trip, you will touch the famous Khardung La pass, which is the highest motorable road in the world at 18,380 feet. DURATION: - 14 Days. ACTUAL BIKING: - 10 Days. DATES: - 25 August to 7 September. SPECIAL EQUIPMENT: - Personal biking equipment HIGHEST ALTITUDE: - Khardung -La 18,380 ft. ITINERARY: 25 Aug Day 01 Reach Delhi by 4 pm > Volvo to Manali 26 Aug Day 02 Reach Manali. Acclimatization ride 27 Aug Day 03 Manali / Kothi - Marrhi (3,281m/10,827 ft.) on bike 38 km Today’s biking is on picturesque upper Manali valley on nice road and solid climbing the entire way. Easy road till village Palchan, 4 km from Solang. From Palchan the climb towards Rohtang Pass begins. We camp at Marrhi, from which Rohtang Pass is only 12 km. 28 Aug Day 04 Marhi- Sisu/ Gondla (3,102 m. -

Existing Tourism Infrastructure and Services in Lahaul Valley of Himachal Pradesh: a Case Study of Hotels / Guest Houses, Home Stays and Travel Agencies

Amity Research Journal of Tourism, Aviation and Hospitality Vol. 01, issue 01, January-June 2016 Existing Tourism Infrastructure and Services in Lahaul Valley of Himachal Pradesh: A Case Study of Hotels / Guest Houses, Home Stays and Travel Agencies Dr. Arvind Kumar Project Fellow-UGC-SAP DRS Level-I (Tourism), Institute of Vocational (Tourism) Studies, Himachal Pradesh University, Summer Hill, Shimla (H.P.) PIN-171005, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The district has occupied an area of Lahaul valley of Himachal Pradesh is one of approximately 3979 metres. The district has the geographically restricted valleys of India. been divided into two division i.e. Lahaul and It remains blocked by Rohtang pass (approx. Spiti. The Lahaul valley is popular among 3979 metres) during winters for almost six adventure tourists during summers and months. During remaining six months tourists monsoon season in India. Geographically, it is make their passage to different tourist places one of the beautiful valleys of the country. It is in Lahaul up to Leh in Jammu and Kashmir. home to numerous tourist attractions like Their passage is assisted by tourist Chnadra and Bhaga rivers, their collision at a infrastructure and services available within the place namely Tandi, Udaipur, Miyar village, valley. The research study has utilized Trilokinath village, Keylong, Guru Ghantal secondary information obtained from office of Monastery, Jispa, Zanskar Sumdo, Shingola deputy director of tourism and civil aviation, pass, Patseo, Baralacha pass, Sarchu, Sissu, Kullu at Manali to assess the existing tourism Koksar and Lady of Keylong glacier etc. Due infrastructure and services within the valley. -

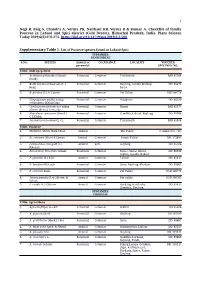

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of Family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti Distr

1 Negi R, Baig S, Chandra A, Verma PK, Naithani HB, Verma R & Kumar A. Checklist of family Poaceae in Lahaul and Spiti district (Cold Desert), Himachal Pradesh, India. Plant Science Today 2019;6(2):270-274. https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.2019.6.2.500 Supplementary Table 1. List of Poaceae species found in Lahaul-Spiti SUBFAMILY: PANICOIDEAE S.No. SPECIES Annual or OCCURANCE LOCALITY VOUCHER perennial SPECIMEN NO. Tribe- Andropogoneae 1. Arthraxon prionodes (Steud.) Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45386 Dandy 2. Bothriochloa ischaemum (L.) Perennial Common Keylong, Gondla, Kailing- DD 85472 Keng ka-Jot 3. B. pertusa (L.) A. Camus Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD100754 4. Chrysopogon gryllus subsp. Perennial Common Madgram DD 85320 echinulatus (Nees) Cope 5. Cymbopogon jwarancusa subsp. Perennial Common Kamri BSD 45377 olivieri (Boiss.) Soenarko 6. Phacelurus speciosus (Steud.) Perennial Common Gondhla, Lahaul, Keylong DD 99908 C.E.Hubb. 7. Saccharum ravennae (L.) L. Perennial Common Trilokinath BSD 45958 Tribe- Paniceae 1. Digitaria ciliaris (Retz.) Koel Annual - Pin Valley C. Sekar (loc. cit.) 2. D. cruciata (Nees) A.Camus Annual Common Pattan Valley DD 172693 3. Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Annual Rare Keylong DD 85186 P.Beauv. 4. Pennisetum flaccidum Griseb. Perennial Common Sissoo, Sanao, Khote, DD 85530 Gojina, Gondla, Koksar 5. P. glaucum (L.) R.Br. Annual Common Lahaul DD 85417 6. P. lanatum Klotzsch Perennial Common Sissu, Keylong, Khoksar DD 99862 7. P. orientale Rich. Perennial Common Pin Valley BSD 100775 8. Setaria pumila (Poir.) Roem. & Annual Common Pin valley BSD 100763 Schult. 9. S. viridis (L.) P.Beauv. Annual Common Kardang, Baralacha, DD 85415 Gondhla, Keylong SUBFAMILY: POOIDEAE Tribe- Agrostideae 1. -

Sub- State Site Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (Lahaul & Spiti and Kinnaur)

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY SUB- STATE SITE BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN (LAHAUL & SPITI AND KINNAUR) MAY-2002 SUBMITTED TO: TPCG (NBSAP), MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT & FOREST,GOI, NEW DELHI, TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT, H.P. SECRETARIAT, SHIMLA-2 & STATE COUNCIL FOR SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT, 34 SDA COMPLEX, KASUMPTI, SHIMLA –9 CONTENTS S. No. Chapter Pages 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Profile of Area 7-16 3. Current Range and Status of Biodiversity 17-35 4. Statement of the problems relating to 36-38 biodiversity 5. Major Actors and their current roles relevant 39-40 to biodiversity 6. Ongoing biodiversity- related initiatives 41-46 (including assessment of their efficacy) 7. Gap Analysis 47-48 8. Major strategies to fill these gaps and to 49-51 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 9. Required actions to fill gaps, and 52-61 enhance/strengthen ongoing measures 10. Proposed Projects for Implementation of 62-74 Action Plan 11. Comprehensive Note 75-81 12. Public Hearing 82-86 13. Synthesis of the Issues/problems 87-96 14. Bibliography 97-99 Annexures CHAPTER- 1 INTRODUCTION Biodiversity or Biological Diversity is the variability within and between all microorganisms, plants and animals and the ecological system, which they inhabit. It starts with genes and manifests itself as organisms, populations, species and communities, which give life to ecosystems, landscapes and ultimately the biosphere (Swaminathan, 1997). India in general and Himalayas in particular are the reservoir of genetic wealth ranging from tropical, sub-tropical, sub temperate including dry temperate and cold desert culminating into alpine (both dry and moist) flora and fauna. -

Ladakhi Knowledge and Western Learning: A

LADAKHI KNOWLEDGE AND WESTERN LEARNING: A. H. FRANCKE’S TEACHERS, GUIDES AND FRIENDS IN THE WESTERN HIMALAYA1 JOHN BRAY (International Association for Ladakhi Studies) The Moravian missionary scholar August Hermann Francke (1870-1930) left a rich legacy of research on Ladakh and the neighbouring regions of the Western Himalaya. Arguably, his greatest single contribution was his Antiquities of Indian Tibet, published in two volumes by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1914 and 1926, which contains translations of the Ladakhi royal chronicle, the La dvags rgyal rabs, as well as other key historical texts. Other important contributions Fig. 1. Francke exploring the ruins of a Buddhist temple in Gompa village, near Leh, Ladakh, 1909. Photo: Pindi Lal. Courtesy of Kern Institute, University of Leiden 1 I gratefully acknowledge advice and support from a number of friends and colleagues over the years, especially Michaela Appel, Stephan Augustin, Isrun Engelhardt, Martin Klingner, Thsespal Kundan, Rüdiger Kröger, Onesimus Ngundu, Lorraine Parsons, Frank Seeliger and Hartmut Walravens. All errors remain my own responsibility. 40 JOHN BRAY include A Lower Ladakhi Version of the Kesar Saga (1905-1941) and dozens of shorter publications on topics ranging from rock inscriptions to music and folk songs.2 In February 1930 Francke died tragically young at Berlin’s Charité hospital, still aged only 59. Among the works that still lay incomplete at the time of his death was a collection of Ladakhi wedding songs that he planned to publish with the ASI. As Elena De Rossi Filibeck (2009, 2016) has explained, the ASI still hoped to bring out the text after Francke’s death. -

Itinerary: Day 01: Delhi/Manali (560 Kms/12 Hrs)-Over Night at Volvo Bus

Itinerary: Day 01: Delhi/Manali (560 kms/12 hrs)-Over night at Volvo bus. Day 02: In Manal-city tour Day 03: Manali/ Rohtang Pass/ Keylong/Jispa (140 kms/ 8 hrs) Day 04: Jispa/ Baralacha Pass/ Sarchu (100 kms/ 7 hrs) Day 05: Sarchu/ Leh (253 kms/ 10 hrs) Day 06: Leh/ Nubra Day 07: Nubra/ Leh Day 08: Leh/ Pangong Lake (160 kms/ 6-7 hrs) Day 09: Pangong/ Leh Day 10: Leh/Sarchu Day 11: Sarchu/ Manali/ (232 kms/10 hrs) Day 12: Depart Manali-over night at Volvo bus PACKAGE INCLUSION Accommodation in hotels/camps/guest house on twin/triple sharing basis as per package option. Check in/ out time is 12 noon MAP basis in hotel (Room+Breakfast+Dinner) starting with dinner in Manali till Breakfast on departure from Manali One Enfield bike (without fuel) (350 cc) per rider and as per the above itinerary Basic spares parts for the bike (any damage/ change of spares payable as extra directly) Accompanied guide one Motorbike Mechanic for the entire tour in bike Inner line Permit (camera fee not included) Volvo tickets from Delhi to Manali and Manali to Delhi Presently applicable taxes Local cuisine Interaction with local people Life time memories Bone fire on departure Gift items on departure from Manali Cost Exclusions : Any airfare/ train fare, Fuel for Bike Entrances to place of visit Any other meal than mentioned in itinerary Any personal or travel Insurance, tips, gratuities, portage, laundry, telephone calls, table drinks or any other expenses of personal nature, any item not specified under cost inclusions. -

Lahaul Spiti

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET LAHAUL & SPITI DISTRICT HIMACHAL PRADESH NORTHERN HIMALAYAN REGION DHARMSALA 2013 “ जल संरण वष - 2013” Contributors Anukaran Kujur Assistant Hydrogeologist Prepared under the guidance of Dalel Singh Head of Office Our Vision Water security through sound management “ जल संरण वष - 2013” GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET Lahaul & Spiti District, Himachal Pradesh CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1-2 2.0 CLIMATE & RAINFALL 3 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOIL TYPES 3-5 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO 5-11 4.1 Hydrogeology 5-9 4.2 Ground Water Resources 9-10 4.3 Ground Water Quality 11 4.4 Status of Ground Water Development 11 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 12 5.1 Ground Water Development 12 5.2 Water Conservation & Artificial Recharge 12 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES & PROBLEMS 12 7.0 AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY 13 8.0 AREAS NOTIFIED BY CGWA / SGWA 13 9.0 RECOMMENDATIONS 13 “ जल संरण वष - 2013” LAHAUL & SPITI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. No Items Statistics 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (sq km) 13,841 ii) Administrative Divisions (2001) a) Number of Tehsil & Sub-tehsils 2 & 1 b) Number of Blocks 2 c) Number of Panchayats 41 d) Number of Villages 521 iii) Population (2011 Census) a) Total population 31,564 persons b) Population Density (persons/sq km) 2 c) Rural & Urban Population in Percentage 100% & Nil d) SC & ST Population (in percent) 7.08 % & 81.44% e) Sex Ratio 903 females per 1000 males iv) Annual Rain fall (2012) 455.40 mm 2. -

Kaul & Thornton. 2013. Adaptation in Himalayan Environment

Reg Environ Change (2014) 14:683–698 DOI 10.1007/s10113-013-0526-3 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Resilience and adaptation to extremes in a changing Himalayan environment Vaibhav Kaul • Thomas F. Thornton Received: 22 February 2013 / Accepted: 25 August 2013 / Published online: 8 September 2013 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Abstract Human communities inhabiting remote and Keywords Climate change adaptation Á Adaptive geomorphically fragile high-altitude regions are particu- capacity Á Resilience Á Disaster risk reduction Á larly vulnerable to climate change-related glacial hazards Mountain environments and hydrometeorological extremes. This study presents a strategy for enhancing adaptation and resilience of com- munities living immediately downstream of two potentially Introduction hazardous glacial lakes in the Upper Chenab Basin of the Western Himalaya in India. It uses an interdisciplinary Context and aim investigative framework, involving ground surveys, par- ticipatory mapping, comparison of local perceptions of In large parts of the Himalaya, proglacial meltwater lakes, environmental change and hazards with scientific data, dammed between glacier termini and unconsolidated ter- identification of assets and livelihood resources at risk, minal moraine deposits, are expanding due to glacial assessment of existing community-level adaptive capacity recession associated with climate change. This is height- and resilience and a brief review of governance issues. In ening the risk of catastrophic glacial lake outburst floods addition to recommending specific actions for securing (GLOFs) for downstream populations (ICIMOD 2003, lives and livelihoods in the study area, the study demon- 2004, 2005; Rosenzweig et al. 2007). The high-altitude strates the crucial role of regional ground-level, commu- Chenab Basin in the Indian Himalayan state of Himachal nity-centric assessments in evolving an integrated approach Pradesh has 31 moraine-dammed glacial lakes (Randhawa to disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation for et al. -

LEH LADAKH BIKE TOUR PACKAGE 2019 Overview Short Itinerary

LEH LADAKH BIKE TOUR PACKAGE 2019 Overview A bike trip to challenging mountainscape of Leh – Ladakh is in top of every passionate biker’s bucket list. The roads are open only few month a year. The Manali – Leh highway connects the lower Himalayas region to high altitude Ladakh region. In this tour we will cross total 7 passes and 3 of them are world highest passes. The journey is full of great adventures and will leave of spellbound. The call of open road and pull of the unknown. Over the course of 9 days you will see all kinds of shifts in weather, terrain and cultures. Snow covered mountains, waterfalls, lakes and deserts will make you feel that you are in heaven. So enjoy the journey with Gulliver Adventures. As someone said – ‘Climb it so you can see the world, not so the world can see you.’ This Package is exclusively for those who want to customize Leh Ladakh bike Tour as per their convenience i.e Day, Date, Time, Itinerary etc. for that we consult, help & manage you to design your own Leh Ladakh Bike Tour Package. To Know Detail Contact Us. Short Itinerary Day 1:- Manali – Jispa Day 2:- Jispa – Sarchu Day 3:- Sarchu – Leh Day 4:- Leh Local Sightseeing Day 5:- Leh – Nubra Day 6:- Nubra – Pangong Day 7:- Pangong – Leh Day 8:- Leh – Jispa Day 9:- Jispa – Manali Detailed Itinerary Day 1:- Manali – Jispa Today morning we will start our journey to Jispa which is 140 km away from Manali. By the time we reach Rohtang Pass(3,978m) you will be amazed by the beauty of Himalayas. -

Archaeology of Lahual Region, Himachal Pradesh

Archaeology of Lahual Region, Himachal Pradesh Ankush Gupta1 1. Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Panjab University, Sector 14, Chandigarh – 160 014, Punjab, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 30 July 2019; Revised: 13 September 2019; Accepted: 20 October 2019 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 7 (2019): 867-874 Abstract: Lahaul is a subdivision of Lahual and Spiti is a district, located in the state of Himachal Pradesh, situated between 31° 44' 57'' and 32° 59' 57'' north latitude and between 76° 46' 29'' and 78° 41' 34'' east longitude. Lahaul is an important center of Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism is also known as Vajrayana Buddhism or Tantric Buddhism. Tibetan branch of Buddhism was introduced in Lahaul in the ninth and tenth century through Tibet. There some Buddhist Sculptures and carvings at various places in Lahaul region, belonging to the early Buddhism. These carvings and sculptures are heritage of Buddhist history of the region. These sculptures are located on the route, which was used both by the travelers or missionaries in the ancient times. It is difficult to say, how and when Buddhism introduced in the region, but these sculptures are the proof that, the region of Lahaul was under the influence of Buddhism prior to 9th-10th century. Present paper is mainly focus on the literary and archaeological evidence to trace the introduction of Buddhism in Lahaul and Spiti. Keywords: Archaeology, Buddhism, Lahual, Rinchen Zangpo, Padmasambhava, Monasteries, Sculptures Introduction Lahaul is a sub-division of Lahual and Spiti is a district, located in the state of Himachal Pradesh, situated between 31° 44' 57'' and 32° 59' 57'' north latitude and between 76° 46' 29'' and 78° 41' 34'' east longitude. -

Study of Roof Collapse in Rohtang Tunnel During Construction/JRMTT 22(1), 2016, 11-20

K.K.Sharma/Study of Roof Collapse in Rohtang Tunnel during Construction/JRMTT 22(1), 2016, 11-20 Journal of Rock Mechanics & Tunnelling Technology (JRMTT) 22 (1) 2016 pp 11-20 Available online at www.isrmtt.com Study of Roof Collapse in Rohtang Tunnel during Construction K. K. Sharma Rohtang Tunnel, Border Roads Organisation, Manali, India Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Collapse in tunnels during construction in Himalayan region may occur due to various reasons. High overburden over tunnel causes increase in rock load. High overburden in weak rock mass creates squeezing ground condition while that in hard/brittle rock may cause rock burst problem. Stress flow along foliation under high overburden and deep seated slope movement may also give rise to high deformation in a particular direction in tunnel. In North portal drive of Rohtang tunnel, alternate layers of migmatite and mica schist are being encountered. Mountain is very steep and overburden rises upto 1.9 km. High deformations are being observed in crown area of the tunnel. Problems being faced in North portal drive include bending of lattice girders, cracks in shotcrete layer, fall of shotcrete/rock block etc. In October 2013, a stretch of crown area of approximately 50 m in length suddenly collapsed. Overburden in this area was approximately 1200 m. It took almost two months to repair the collapsed area. To counter the problems and prevent such occurrence in future; a thick layer of shotcrete, longer rock bolts, regular repairing of cracked shotcrete layers and daily 3D deformation monitoring are being followed. Keywords: Collapse; Squeezing; Overburden; Stress; Foliation; 3D monitoring 1.