Pigments and Painting Techniques of Roman Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abraham (Hermit) 142F. Aristode 160 Acacius (Bishop Atarbius (Bishop Of

INDEX Abraham (hermit) 142f. Aristode 160 Acacius (bishop Atarbius (bishop of Caesarea) 80f., 86f., of Neocaesarea) 109f., 127 91 Athanasius 63, 67ff., 75 Acacius (bishop Athanasius of Balad 156, 162 of Beroea) 142ff. Athenodorus (brother Aelianus 109 of Gregory al-Farabi 156 Thaumaturgus) 103, 105, Alexander (bishop 133 of Comana) I 26f., 129, Athens 120 132 Augustine 9-21, 70 Alexander (of the Cassiciacum Dialogues 9, 15ff. "Non-Sleepers" Corifessions 9-13, 15, monastery) 203, 211 18, 20f. Alexander (patriarch De beata vita 16ff. of Antioch) 144 De ordine 16ff. Alexander of Retractions 19 Abonoteichos 41 Soliloquies 19f. Alexander Severus Aurelian (emperor (emperor 222-235) 47 270-275) 121 Alexandria 37, 39f., 64, Auxentios 205 82, 101, 104, 120, Babai 172 n. II, 126f., 129 173ff. n. 92, 143, Babylas 70 156, 215 Baghdad 156 Alexandrian Christology 68 Bardesanism/Bardesanites 147 Amaseia 128 Barhadbeshabba 'Arbaya 145 Ambrose 70, 91 Barnabas 203 n. 39 Basil of Caeserea 109f., 117, Anastasios (monk) 207 121ff., 126f., Anastasius (= Magundat) 171 131, 157, Ancyra 113 166 Andrew Kalybites 207 Basilides 32, 37ff. Andrew the Fool 203 Beroea 141, 142 Annisa 112f. Berytus 101, 103f., Antioch 82, 105, 120 I I If., 155, 160, 215 Caesarea (Cappadocia) 129 Antiochene theology 72f., 143 Caesarea (Palestine) 80ff., 87, Antiochos the African 205 91, 92, 100, Antony 63,69f., 101, 103ff., 75f. 120 Antony / Antoninus Cappadocia 46ff., 53, (pupil of Lucian) 65 122 Apelles 51 Carpocrates 32, 39, 41 Arius/ Arianism/ Arians 65ff., 80ff., Carthage 47,49, 51, 92, 148 53ff., 57f. 224 INDEX Cataphrygian(s) 50ff., 56, 59 David of Thessalonike 205 Chaereas (comes) 140 Dcmosthenes (vicarius Chalcedon 75 of Pontica) III Chosroes II 17Iff., 175, Diogenes (bishop 177, I 79f., of Edessa) 144 182, 184, Dionysius (pope 259~269) 106 188 Doctrina Addai 91 n. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Background The present study concerns materials used for Pompeian wall paintings.1 In focus are plasters of the early period, related to the Samnite period and the so called First style. My earlier experiences the field of ancient materials were studies of Roman plasters at the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta and fragments of wall decorations from the demolished buildings underneath the church San Lorenzo in Lucina in Rome. These studies led to the hypothesis that technology reflects not only the natural (geographical) resources available but also the ambitions within a society, a moment in time, and the economic potential of the commissioner.2 Later, during two years within the Swedish archaeological project at Pompeii, it was my task to study the plasters used in one of the houses of insula V 1, an experience that led to the perception that specific characteristics are linked to plasters used over time. In the period 2003-2005, funding by the Swedish Research Council made possible to test the hypotheses. The present method was developed at insula I 9 and the Forum of Pompeii with the approval of the Soprintendenza archeological di Pompei and in collaboration with the directors of two international archaeological teams.3 It became evident that plaster’s composition changes over time, and eight groups of chronologically pertinent plasters were identified and defined A-H. Based on these results, I assume there is a connection between the typology and the relative chronology in which the plasters appear on the walls. I also believe these factors are related not only in single buildings or quarters but over the site and that, hypothetically, the variations observed are related to technology, craftsmanship and fashion. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Homer in Philo: Scylla's Myth in Philonic Philosophical Context

Chapter 10 Homer in Philo: Scylla’s Myth in Philonic Philosophical Context Marta Alesso The Homeric hypotext emerges in Philo by way of quotations or allusions on approximately sixty occasions. Homer is mentioned by name five times.1 Philo was not the only one to use Homer for his purposes of allegorical reading as a method. In the Hellenistic period, two ways of dealing with the problem of the apprehension of the meaning of a sacred text are foremost used. On the one hand the understanding of the Homeric poems under the light of a monotheis- tic perspective and, on the other, the reading of the Pentateuch illuminated by Greek philosophy. This practice, as a manner of understanding both the Bible and Homer’s poems, becomes after a few centuries a mode of interpretation of every text, when we arrive at Christian allegorism. Paradigmatic examples will be the Christian allegorism of Clement, who applied to Jesus the same argu- ments that Philo had used on Moses without mentioning his source; of Origen, in the polemic against Celso; of Ambrose, the bishop of Milan who practically plagiarized the Philonic texts. Ideas about Greek cosmology and cosmogony, genetically illuminated by etymologies, constitute the main instrumental basis of the exegetical method of Heraclitus (Homeric Problems), Lucius Annaeus Cornutus (Compendium of Greek Theology) and the Ps. Plutarch (On Homer), whose main objective is not to reveal the deep meaning of proper names and epithets (in the Stoic way) but to analyze extensive mythical episodes maintaining the coherence between the allegorical reading and the epic narrative, in order to demonstrate that Homer is the first and most enlightened enunciator of all philosophical conceptions about the physis of the universe. -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

40 Common Minerals and Their Uses

40 Common Minerals and Their Uses Aluminum Beryllium The most abundant metal element in Earth’s Used in the nuclear industry and to crust. Aluminum originates as an oxide called make light, very strong alloys used in the alumina. Bauxite ore is the main source aircraft industry. Beryllium salts are used of aluminum and must be imported from in fluorescent lamps, in X-ray tubes and as Jamaica, Guinea, Brazil, Guyana, etc. Used a deoxidizer in bronze metallurgy. Beryl is in transportation (automobiles), packaging, the gem stones emerald and aquamarine. It building/construction, electrical, machinery is used in computers, telecommunication and other uses. The U.S. was 100 percent products, aerospace and defense import reliant for its aluminum in 2012. applications, appliances and automotive and consumer electronics. Also used in medical Antimony equipment. The U.S. was 10 percent import A native element; antimony metal is reliant in 2012. extracted from stibnite ore and other minerals. Used as a hardening alloy for Chromite lead, especially storage batteries and cable The U.S. consumes about 6 percent of world sheaths; also used in bearing metal, type chromite ore production in various forms metal, solder, collapsible tubes and foil, sheet of imported materials, such as chromite ore, and pipes and semiconductor technology. chromite chemicals, chromium ferroalloys, Antimony is used as a flame retardant, in chromium metal and stainless steel. Used fireworks, and in antimony salts are used in as an alloy and in stainless and heat resisting the rubber, chemical and textile industries, steel products. Used in chemical and as well as medicine and glassmaking. -

Discussion and Conclusions

Discussion and Conclusions It is clear that the plasters investigated fall into very distinct groups. The vast majority of samples are clearly distinctive, and there is generally no problem in placing them into specific groups, determined by macroscopical observations. These groups of plasters are always found in the same sequence, wherever a sequence of plasters is visible. Eight different groups of plasters have been identified and are listed in chronological order from A to H. The earliest plaster type is not necessarily the same in all buildings, though this was sometimes the case. Not all phases are represented in every house, probably because the owner did not need or have any wish to redecorate. Plasters in group C, for example, were used for 2nd style decorations in three houses in insula I 9. At the Forum, such a plaster was found only in the cella of the Temple of Jupiter. On the other hand, plasters in group E, connected with the 3rd style, were found in all houses in the insula and was common also at the Forum, used in all buildings except for the Basilica, where only earlier plasters were found, and the Macellum, which had only later decorations. The chronological order of groups and phases is clear, but what do we know about the correlation between plasters and styles? This is more problematic, not least of all since there is no unconditional agreement on their dating. When discussing with myself, I think of plasters in terms of “1st style”, “2nd” and so on, since the typologies are clear and I know this kind of definition is not explicit. -

A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India's Wall Paintings

heritage Review A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India’s Wall Paintings Anjali Sharma 1 and Manager Rajdeo Singh 2,* 1 Department of Conservation, National Museum Institute, Janpath, New Delhi 110011, India; [email protected] 2 National Research Laboratory for the Conservation of Cultural Property, Aliganj, Lucknow 226024, India * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Iron-containing earth minerals of various hues were the earliest pigments of the prehistoric artists who dwelled in caves. Being a prominent part of human expression through art, nature- derived pigments have been used in continuum through ages until now. Studies reveal that the primitive artist stored or used his pigments as color cakes made out of skin or reeds. Although records to help understand the technical details of Indian painting in the early periodare scanty, there is a certain amount of material from which some idea may be gained regarding the methods used by the artists to obtain their results. Considering Indian wall paintings, the most widely used earth pigments include red, yellow, and green ochres, making it fairly easy for the modern era scientific conservators and researchers to study them. The present knowledge on material sources given in the literature is limited and deficient as of now, hence the present work attempts to elucidate the range of earth pigments encountered in Indian wall paintings and the scientific studies and characterization by analytical techniques that form the knowledge background on the topic. Studies leadingto well-founded knowledge on pigments can contribute towards the safeguarding of Indian cultural heritage as well as spread awareness among conservators, restorers, and scholars. -

The Reception of Alexander in Hellenistic Art

chapter 6 The Reception of Alexander in Hellenistic Art Olga Palagia Introduction Alexander appears to have invented his own image as a youthful ruler who preserved his young looks by shaving his chin contrary to usual practice, and by growing his hair longer than average, swept up from the forehead to form an anastole. In addition, he was said to have a melting gaze and crooked neck.1 Alexander’s own favourite artists, the sculptor Lysippus, the painter Apelles and the gem-cutter Pyrgoteles, disseminated his official image during his lifetime. Other artists, like Leochares and Euphranor of the Attic School, also attempted his portrait, not least during the lifetime of his father, Philip ii, when Alexander was crown prince.2 None of these works has come down to us. The only inscribed portrait of Alexander is the Azara herm of the Roman period, which is heavily restored.3 It is thought to reflect an original by Lysippus though this is sometimes disputed. It does, nevertheless, provide a blueprint for Alexander’s appearance enabling us to recognize his image. The Hellenistic period begins with Alexander’s death in Babylon in 323 and ends with Cleopatra vii’s death in Alexandria in 30bc. Shortly after his death in 323, Alexander’s empire disintegrated and was divided into the kingdoms of the Successors.4 Each one of them claimed him in some manner and depended 1 On the physical characteristics of Alexander, see Plut. Mor. 180b and 335a–b; Alex. 4.1–7; Athen. 13.565a; Ael. vh 12.14. T. Hölscher, Ideal und Wirklichkeit in den Bildnissen Alexanders desGrossen (Heidelberg: CarlWinter, 1971), 24–42; A. -

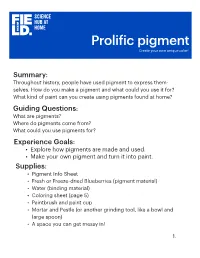

Prolific Pigmentfinal4.19.20 Copy

Proliic pigment Create your own unique color! Summary: Throughout history, people have used pigment to express them- selves. How do you make a pigment and what could you use it for? What kind of paint can you create using pigments found at home? Guiding Questions: What are pigments? Where do pigments come from? What could you use pigments for? Experience Goals: • Explore how pigments are made and used. • Make your own pigment and turn it into paint. Supplies: • Pigment Info Sheet • Fresh or Freeze-dried Blueberries (pigment material) • Water (binding material) • Coloring sheet (page 5) • Paintbrush and paint cup • Mortar and Pestle (or another grinding tool, like a bowl and large spoon) • A space you can get messy in! 1. Steps: 1. Explore Pigments a. Explore the Pigment Info Sheet to learn about pigment and how it is used. b. Think about what could create pigment in your home. Is there anything in your kitchen? How about colorful plants outside? c. We will use blueberries to make our color! You can ind the recipe in Step 3. What other colors could you create? What would you paint with them? 2. Make Your Pigment a. Gather your pigment material. Usually a pigment used in painting will be powdered, but can also be in juice form. Crushed up freeze dried fruits like blueberries make for an excellent pigment powder! b. Grind or mash up your pigment material. If using fresh blueberries, mash them then strain out the juice using a kitchen strainer. With frozen or freeze dried blueberries, use a mortar and pestle (or similar items like a bowl and large spoon) to grind them into a ine powder. -

Technological Features of the Chalcolithic Pottery from Târpești (Neamț County, Eastern Romania)

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry Vol. 19, No 3, (2019), pp. 93-104 Open Access. Online & Print. www.maajournal.com DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3541108 TECHNOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE CHALCOLITHIC POTTERY FROM TÂRPEȘTI (NEAMȚ COUNTY, EASTERN ROMANIA) Florica Mățău*1, Ovidiu Chișcan2, Mitică Pintilei3, Daniel Garvăn4, Alexandru Stancu2 1Interdisciplinary Research Institute, Science Department-ARHEOINVEST Platform, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Lascăr Catargi, no. 54, 700107, Iasi, Romania 2Faculty of Physics, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Carol I, no. 11, 700506, Iasi, Romania 3Department of Geology, Faculty of Geography and Geology, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Carol I, no. 11, 700506, Iasi, Romania 4Buzău County Museum, Castanilor, no. 1, 120248, Buzău, Romania Received: 11/10/2019 Accepted: 14/11/2019 *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The technological parameters of representative pottery samples attributed to Precucuteni (5050-4600 cal BC) and Cucuteni (4600-3500 cal BC) cultures identified at Târpești (Neamț County, Eastern Romania) were determined using a complex archaeometric approach. The site is located in the north-eastern part of the present-day Romania occupying a small plateau situated in a hilly region. In order to evaluate the raw materials and the firing process we have used optical microscopy (OM), X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) and magnetic measurements. Further on, the XRPD data were statistically treated using hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) taking into account position and peak intensity, the Euclidian distance as metric and the average linkage method as a linkage basis for gaining a more refined estimation of the mineralogical transformations induced by the firing process and for defining homogenous group of samples.