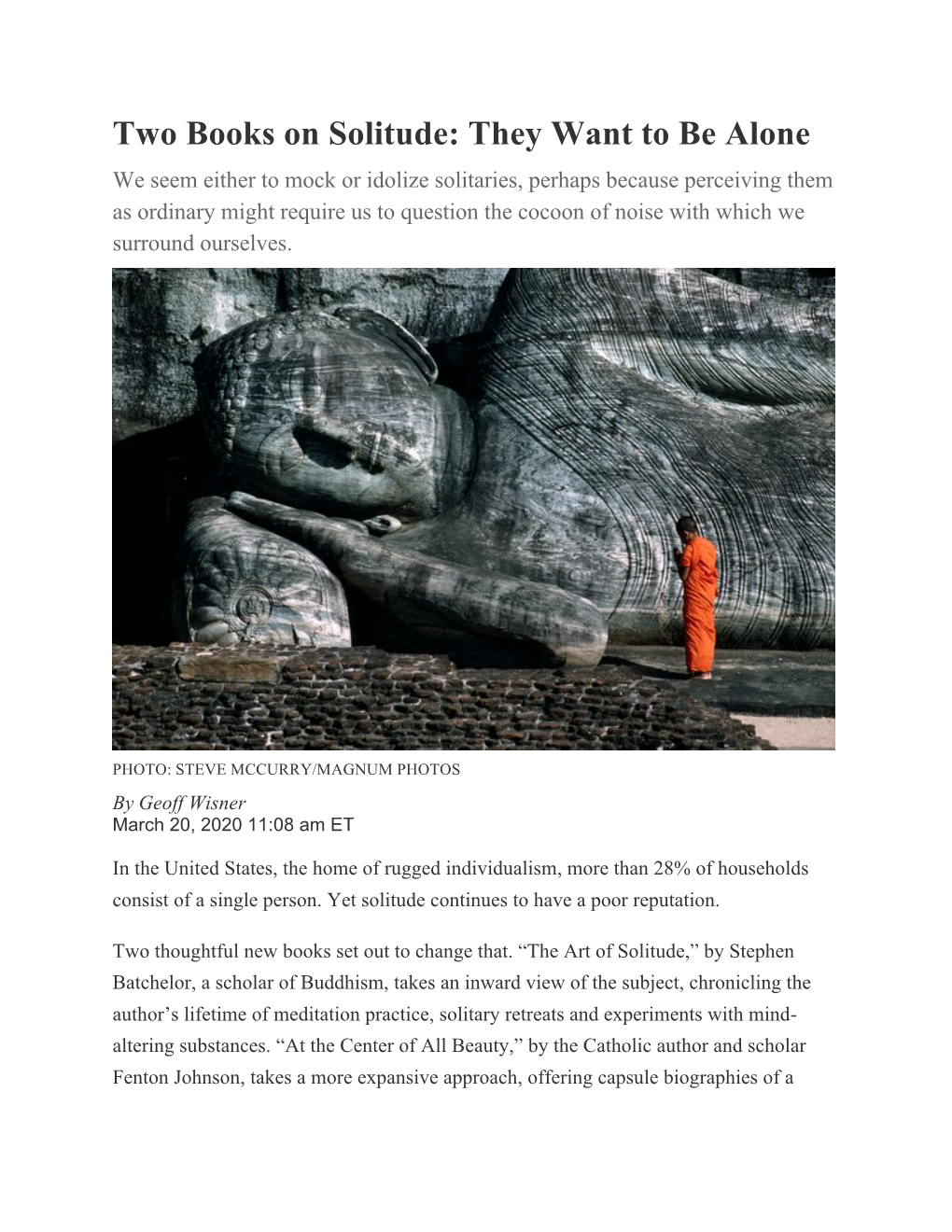

Two Books on Solitude

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katsushika Hokusai and a Poetics of Nostalgia

ACCESS: CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN EDUCATION 2015, VOL. 33, NO. 1, 33–46 https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.964158 Katsushika Hokusai and a Poetics of Nostalgia David Bell College of Education, University of Otago ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article addresses the activation of aesthetics through the examination of cultural memory, Hokusai, an acute sensitivity to melancholy and time permeating the literary and ukiyo-e, poetic allusion, nostalgia, mono no aware pictorial arts of Japan. In medieval court circles, this sensitivity was activated through a pervasive sense of aware, a poignant reflection on the pathos of things. This sensibility became the motivating force for court verse, and ARTICLE HISTORY through this medium, for the mature projects of the ukiyo-e ‘floating world First published in picture’ artist Katsushika Hokusai. Hokusai reached back to aware sensibilities, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 2015, Vol. 47, No. 6, subjects and conventions in celebrations of the poetic that sustained cultural 579–595 memories resonating classical lyric and pastoral themes. This paper examines how this elegiac sensibility activated Hokusai’s preoccupations with poetic allusion in his late representations of scholar-poets and the unfinished series of Hyakunin isshu uba-ga etoki, ‘One hundred poems, by one hundred poets, explained by the nurse’. It examines four works to explain how their synthesis of the visual and poetic could sustain aware themes and tropes over time to maintain a distinctive sense of this aesthetic sensibility in Japan. Introduction: Mono no aware How can an aesthetic sensibility become an activating force in and through poetic and pictorial amalgams of specific cultural histories and memories? This article examines how the poignant aesthetic sensibility of mono no aware (a ‘sensitivity to the pathos of things’) established a guiding inflection for social engagements of the Heian period (794–1185CE) Fujiwara court in Japan. -

From Grasping to Emptiness – Excursions Into the Thought-World of the Pāli Discourses (2)

From Grasping to Emptiness – Excursions into the Thought-world of the Pāli Discourses (2) Anālayo © 2010 Anālayo Published by The Buddhist Association of the United States 2020 Route 301, Carmel, New York 10512 Printed in Taiwan Cover design by Laurent Dhaussy ISBN 978-0-615-25529-3 Introduction 3 1. Grasping / Upādāna 5 1.1 Grasping at Sensual Pleasures 5 1.2 Grasping at Views 7 1.3 Grasping at Rules and Observances 9 1.4 Grasping at a Doctrine of Self 10 1.5 The Five Aggregates [Affected by] Clinging 13 1.6 Grasping and Nibbāna 15 1.7 Freedom from Grasping 16 2. Personality View / Sakkāyadihi 19 2.1 Manifestations of Personality View 19 2.2 Removal of Personality View 24 3. Right View / Sammādihi 27 3.1 Wrong View 27 3.2 Right View and Investigation 29 3.3 Right View as the Forerunner of the Path 31 3.4 Arrival at Right View 33 3.5 Right View and the Four Noble Truths 34 4. Volitional Formations / Sakhārā 39 4.1 Sakhāras as an Aggregate 40 4.2 Sakhāras as a Link in Dependent Arising 44 4.3 Sakhāras in General 48 5. Thought / Vitakka 55 5.1 The Ethical Perspective on Thought 56 5.2 The Arising of Thought 57 5.3 The Vitakkasahāna-sutta 60 5.4 Vitakka in Meditation 64 5.5 Thought Imagery 66 6. Wise Attention / Yoniso Manasikāra 69 6.1 Wise ( Yoniso ) 69 6.2 Attention ( Manasikāra ) 72 6.3 The Implications of Wise Attention 72 6.4 The Importance of Wise Attention 78 7. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of MISSOURI EASTERN DIVISION JEFFREY D. BRIDGES, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) V. )

Case: 4:06-cv-01200-ERW Doc. #: 16 Filed: 07/26/07 Page: 1 of 40 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI EASTERN DIVISION JEFFREY D. BRIDGES, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case number 4:06cv1200 ERW ) TCM MICHAEL J. ASTRUE, ) Commissioner of Social Security,1 ) ) Defendant. ) REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF UNITED STATES MAGISTRATE JUDGE This is an action under 42 U.S.C. § 405(g) for judicial review of the final decision of Michael Astrue, the Commissioner of Social Security ("Commissioner"), denying Jeffrey D. Bridges disability insurance benefits ("DIB") under Title II of the Social Security Act ("the Act"), 42 U.S.C. §§ 401-433. Plaintiff has filed a brief in support of his complaint; the Commissioner has filed a brief in support of his answer. The case was referred to the undersigned United States Magistrate Judge for a review and recommended disposition pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 636(b). Procedural History Jeffrey D. Bridges ("Plaintiff") applied for DIB in December 2003, alleging he was disabled as of January 2000 by Wegener's disease, stress, aches and pains, memory loss, 1Mr. Astrue was sworn in as the Commissioner of Social Security on February 12, 2007, and is hereby substituted as defendant pursuant to Rule 25(d)(1) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Case: 4:06-cv-01200-ERW Doc. #: 16 Filed: 07/26/07 Page: 2 of 40 PageID #: <pageID> depression, high blood pressure, and anxiety. (R. at 48-50.)2 This application was denied initially and after a hearing held in November 2004 before Administrative Law Judge ("ALJ") James B. -

Factors Influencing Depression in Men: a Qualitative Investigation

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Nursing College of Nursing 2015 Factors Influencing Depression in Men: A Qualitative Investigation Lori A. Mutiso University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mutiso, Lori A., "Factors Influencing Depression in Men: A Qualitative Investigation" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Nursing. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/nursing_etds/15 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Nursing at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Nursing by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

From Grasping to Emptiness – Excursions Into the Thought-World of the Pāli Discourses (2)

From Grasping to Emptiness – Excursions into the Thought-world of the Pāli Discourses (2) Anālayo © 2010 Anālayo Published by The Buddhist Association of the United States 2020 Route 301, Carmel, New York 10512 Printed in Taiwan Cover design by Laurent Dhaussy ISBN 978-0-615-25529-3 Introduction 3 1. Grasping / Upādāna 5 1.1 Grasping at Sensual Pleasures 5 1.2 Grasping at Views 7 1.3 Grasping at Rules and Observances 9 1.4 Grasping at a Doctrine of Self 10 1.5 The Five Aggregates [Affected by] Clinging 13 1.6 Grasping and Nibbāna 15 1.7 Freedom from Grasping 16 2. Personality View / Sakkāyadihi 19 2.1 Manifestations of Personality View 19 2.2 Removal of Personality View 24 3. Right View / Sammādihi 27 3.1 Wrong View 27 3.2 Right View and Investigation 29 3.3 Right View as the Forerunner of the Path 31 3.4 Arrival at Right View 33 3.5 Right View and the Four Noble Truths 34 4. Volitional Formations / Sakhārā 39 4.1 Sakhāras as an Aggregate 40 4.2 Sakhāras as a Link in Dependent Arising 44 4.3 Sakhāras in General 48 5. Thought / Vitakka 55 5.1 The Ethical Perspective on Thought 56 5.2 The Arising of Thought 57 5.3 The Vitakkasahāna-sutta 60 5.4 Vitakka in Meditation 64 5.5 Thought Imagery 66 6. Wise Attention / Yoniso Manasikāra 69 6.1 Wise ( Yoniso ) 69 6.2 Attention ( Manasikāra ) 72 6.3 The Implications of Wise Attention 72 6.4 The Importance of Wise Attention 78 7. -

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Toni Morrison's Beloved

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:4 April 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ================================================================ Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Toni Morrison’s Beloved Nidhin Johny, M.Phil. Research Scholar and Subin P. S., Ph.D. Scholar ================================================================== Courtesy: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/117647/beloved-by-toni- morrison/9780307264886/ Abstract Experiencing trauma is an inevitable part of human life, we must go through extremely difficult situation though we like it or not. History is painted in blood. Literature provides an amble medium for venting out certain emotions. Human beings are exposed to worst situation in the course of history and most of the rational race has come out of it without unaltered mental and spiritual sanctity. But not all of them were lucky despite the human ability to adapt and survive some traumatic experience has shaken up the whole composition of physical mental and psychological wellbeing of these people. Post- traumatic stress disorder gives a theoretical framework on how people’s conception of the world and themselves and how personal and shared experience are intertwined. In Toni Morrison’s Beloved we see the psychological effect of the personal and collective trauma of slavery. Each of the characters though out of slavery are still haunted by the ghosts of their past, their ================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:4 April 2018 Nidhin Johny, M.Phil. Research Scholar and Subin P. S., Ph.D. Scholar Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Toni Morrison’s Beloved 221 bodies are emancipated their minds still carries the burden of memory. -

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, an Initiator of the Psychological Thriller

MEISART, MICHELE F. Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu: An Initiator of the Psychological Thriller. (1973) Directed by: Dr. Arthur W. Dixon. Pp.100. Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, an important figure in the world of supernatural literature, was born in Ireland and as a writer could never escape his Irish origin. In his short stories the themes as well as the characters are Irish and in his novels the atmosphere is definitely Irish. The Irish people furnished Le Fanu with a never ending source for the psychological study of characters of his novels. His power of penetration into the human mind was enhanced by his own neurosis and his personal grief (when his wife died he became a recluse). His neurosis and his grief also caused his novels to become more indepth studies of death, murder and retribution. The strength of his stories lies in the fact that they are based on his own experience. The bases for his weirdly horrible tales, specifically the novels Uncle Silas, Checkmate, Wylder's Hand and Willing to Die are the following: one, the reader shares in the hallu- cinations and premonitions of the victim, two, he also shares in the identity of the agent of terror. In supernatural literature Le Fanu is between the gothic period and the modern supernatural fiction. There are elements of both in his own stories. The natural elements, typically gothic, condition the reader psychologically. Le Fanu, deeply learned in Swedenborgianism, believed that "men are constantly surrounded by preternatural powers," represented by vegetation, the moon or a house. These preternatural influences create an effect on the characters in the stories. -

The Application of Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Linda Hogan’S Solar Storms and Eden Robinson’S Monkey Beach

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 5-2020 THE CATASTROPHIC OPEN WOUND: THE APPLICATION OF COMPLEX POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER IN LINDA HOGAN’S SOLAR STORMS AND EDEN ROBINSON’S MONKEY BEACH Kawther I. Abbas [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Abbas, Kawther I., "THE CATASTROPHIC OPEN WOUND: THE APPLICATION OF COMPLEX POST- TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER IN LINDA HOGAN’S SOLAR STORMS AND EDEN ROBINSON’S MONKEY BEACH" (2020). All NMU Master's Theses. 621. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/621 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE CATASTROPHIC OPEN WOUND: THE APPLICATION OF COMPLEX POST- TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER IN LINDA HOGAN’S SOLAR STORMS AND EDEN ROBINSON’S MONKEY BEACH By Kawther I. Abbas THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Office of Graduate Education and Research April 2020 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM THE CATASTROPHIC OPEN WOUND: THE APPLICATION OF COMPLEX POST- TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER IN LINDA HOGAN’S SOLAR STORMS AND EDEN ROBINSON’S MONKEY BEACH This thesis by Kawther I. Abbas is recommended for approval by the student’s Thesis Committee and Department Head in the Department of English and by the Dean of Graduate Education and Research. -

The Harmony of Illusions the Harmony of Illusions

THE HARMONY OF ILLUSIONS THE HARMONY OF ILLUSIONS I NVENTING POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER Allan Young PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY Copyright 1995 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Young, Allan, 1938– The harmony of illusions : inventing post-traumatic stress disorder / Allan Young. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-691-03352-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Post-traumatic stress disorder—Philosophy. 2. Social epistemology. I. Title. RC552.P67Y68 1995 616.85′21—dc20 95-16254 This book has been composed in Times Roman Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources Printed in the United States of America by Princeton Academic Press 10987654321 For Roberta Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 3 PART I: THE ORIGINS OF TRAUMATIC MEMORY One Making Traumatic Memory 13 Two World War I 43 PART II: THE TRANSFORMATION OF TRAUMATIC MEMORY Three The DSM-III Revolution 89 Four The Architecture of Traumatic Time 118 PART III: POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER IN PRACTICE Five The Technology of Diagnosis 145 Six Everyday Life in a Psychiatric Unit 176 Seven Talking about PTSD 224 Eight The Biology of Traumatic Memory 264 Conclusion 287 Notes 291 Works Cited 299 Index 321 Acknowledgments I OWE a debt to colleagues and friends in the Department of Social Studies of Medicine and the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University: I thank Don Bates, Alberto Cambrosio, Margaret Lock, Faith Wallis, George Weisz, and Laurence Kirmayer for their invaluable advice. -

Battlefield Trauma (Exposure, Psychiatric Diagnosis and Outcomes)

Battlefield Trauma (Exposure, Psychiatric Diagnosis and Outcomes) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By ROBERT ANDREW COXON November 2008 The University of Adelaide, Australia Centre for Military and Veterans’ Health School of Population Health and Clinical Practice Faculty of Health Sciences REFERENCES Aaronson, N.K., Acquadro, C., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Bucquet, D., Bullinger, M., Bungay, K., Fukuhara, S., Gandek, B. & Keller, S. et al. (1992) International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Quality of Life Research, 1, 349- 351. Acierno, R., Resnick, H.S., Kilpatrick, D.G., Saunders, B.E., & Best, C.L., (1999). Risk factors for rape, physical assault, and posttraumatic stress disorder in women: examination of differential multivariate relationships. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13, 542-563. Adler, A.B.,Vaitkus, M.A. & Martin, J.A., (1996). Combat exposure and posttraumatic stress symptomatology among U.S. soldiers deployed to the Gulf War. Military Psychology, 8, 1-14. Alexander, D.A. & Wells, A., (1991). Reactions of police officers to body handling after a major disaster: A before and after comparison: British Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 547-555. American Psychiatric Association. (1952). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. First Edition. Washington D.C., American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. (1968). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Second Edition. Washington D.C., American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third Edition. Washington D.C., American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Third Edition (Revised). Washington D.C., American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. -

The Forensic Examination

The Forensic Examination A Handbook for the Mental Health Professional Alberto M. Goldwaser Eric L. Goldwaser 123 The Forensic Examination Alberto M. Goldwaser · Eric L. Goldwaser The Forensic Examination A Handbook for the Mental Health Professional Alberto M. Goldwaser Eric L. Goldwaser Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Sheppard Pratt Health System Psychiatry New York University School of Medicine University of Maryland Medical Center Jersey City, NJ Baltimore, MD USA USA ISBN 978-3-030-00162-9 ISBN 978-3-030-00163-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00163-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018959462 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

A Sense of Loneliness and Alienation Experiences by the Individual in Anita Desai’S Fire on the Mountain

Notions Vol. 7 No. 4, 2016 ISSN: (P) 0976-5247, (e) 2395-7239 ICRJIFR IMPACT FACTOR 3.9531 A Sense of Loneliness and Alienation Experiences by the Individual in Anita Desai’s Fire on The Mountain Dr. R. Krishnaveni Assistant Professor Department of English LRG Govt. Arts College for Women Tirupur - 641 604 E-Mail ID: [email protected] Abstract The Indo-Anglian novel has enriched itself with the Indian Independence Movement, materialism and spiritualism, East-west encounter and tradition and modernity as the common themes till the 1970’s. Anita Desai creates a character in order to tell a tale and articulate her vision of life. Almost all her novels portray female protagonists as hyper-sensitive, solitary and introspective. In Fire on the Mountain, Nanda Kaul, Raka and Ila are isolated from society because of their guilty consciences, and their desire to hide their humiliation and suffer from alienation. These three female characters are embodiments of the alienation experienced by the individual in a hostile universe. Her characters are living individuals, interested in life with its hopes, dejections, and chaotic flow. This article has explored how Desai has portrayed the decline of human relationships and how some of the characters want to lead a life of solitude as in the case of Nanda, Raka and Ila. Keywords: loneliness, alienation, solitary and materialism. The Indo-Anglian novel has now gained an international recognition. It has enriched itself with the Indian Independence Movement, materialism and spiritualism, East-west encounter and tradition and modernity as the common themes till the 1970’s.