View in PDF Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Dearborn River High Bridge other name/site number: 24LC130 2. Location street & number: Fifteen Miles Southwest of Augusta on Bean Lake Road not for publication: n/a vicinity: X city/town: Augusta state: Montana code: MT county: Lewis & Clark code: 049 zip code: 59410 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_ nomination _ request for detenj ination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the proc urf I and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criterfi commend thatthis oroperty be considered significant _ nationally X statewide X locafly. Signa jre of oertifying officialn itle Date Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification , he/eby certify that this property is: 'entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register_ _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): _________________ Dearborn River High Bridge Lewis & Clark County. -

Zenas King and the Bridges of New York City

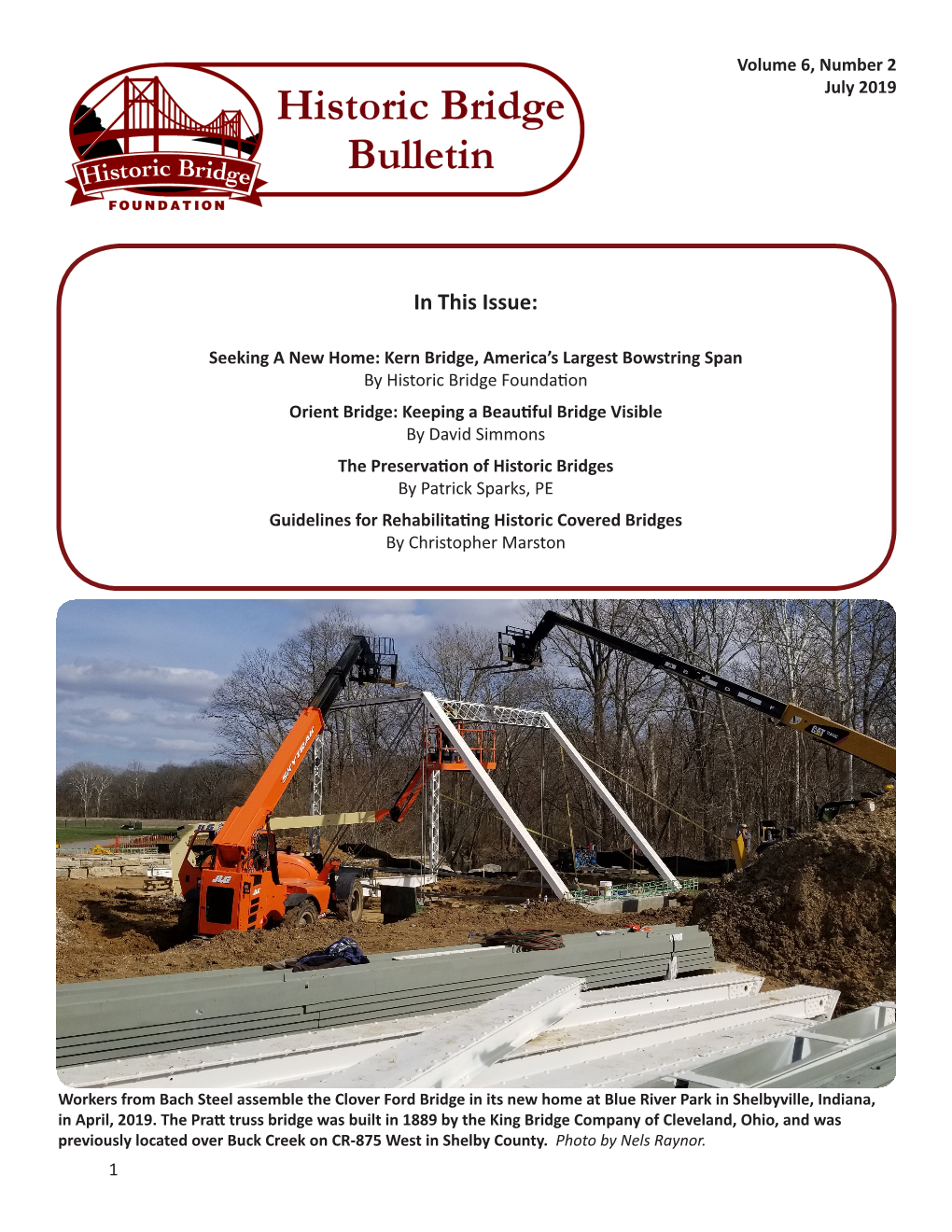

Volume 1, Number 2 November 2014 From the Director’s Desk In This Issue: From the Director’s Desk Dear Friends of Historic Bridges, Zenas King and the Bridges of New Welcome to the second issue of the Historic Bridge York City (Part II) Bulletin, the official newsletter of the Historic Bridge Hays Street Bridge Foundation. Case Study: East Delhi Road Bridge As many of you know, the Historic Bridge Foundation advocates nationally for the preservation Sewall’s Bridge of historic bridges. Since its establishment, the Historic Bridge Collector’s Historic Bridge Foundation has become an important Ornaments clearinghouse for the preservation of endangered bridges. We support local efforts to preserve Set in Stone significant bridges by every means possible and we Upcoming Conferences proactively consult with public officials to devise reasonable alternatives to the demolition of historic bridges throughout the United States. We need your help in this endeavor. Along with Zenas King and the Bridges our desire to share information with you about historic bridges in the U.S. through our newsletter, of New York City (Part II) we need support of our mission with your donations to the Historic Bridge Foundation. Your generous King Bridge Company Projects in contributions will help us to publish the Historic New York City Bridge Bulletin, to continue to maintain our website By Allan King Sloan at www.historicbridgefoundation.com, and, most importantly, to continue our mission to actively promote the preservation of bridges. Without your When Zenas King passed away in the fall of 1892, help, the loss of these cultural and engineering his grand plan to build two bridges across the East landmarks threatens to change the face of our nation. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

MRS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_______________________________________ _____Iron and Steel Bridges in Minnesota________________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts____________________________________________ Historic Iron and Steel Bridges in Minnesota, 1873-1945 C. Geographical Data State of Minnesota See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Nina M. Archabal Date State Historic Preservation Officer______________________ __________ , _____ State or Federal agency and bureau Minriesota Historical Society I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. Signature of the Keeper of the National Register E. Statement of Historic Contexts Discuss each historic context listed in Section B. -

Welcome to Our First Digital Newsletter by Paul Brandenburg, Board President of the Historic Bridge Foundation

Volume 1, Number 1 Summer 2014 Welcome To Our First Digital Newsletter By Paul Brandenburg, Board President of the Historic Bridge Foundation Welcome to the new electronic edition of the Historic Bridge Foundation newsletter--Historic Bridge Bulletin. Providing relevant information and education regarding all aspects of historic bridges has always been at the core of our mission. Earlier this year, the Board jumped at the opportunity to restart the “publication” of a newsletter using the latest electronic technology. We were further encouraged by the response received when we requested articles for publication. We now have commitments to complete the first three newsletters. We enjoy hearing about your work with historic bridges. Please consider sharing your experiences by contributing an article for future newsletters. Clearly a project of this magnitude does not happen by itself and I thank Kitty for the excellent work as Executive Director and Nathan as Editor for the Historic Bridge Bulletin in producing a quality product for your review in record time. bridge maintains the same center of gravity in all operating Chicago’s Movable positions. Today, across the country, the fixed trunnion is one of the two most common types of bascule bridge, the other common type being the Scherzer-style rolling Highway Bridges lift bascule which include A Mixed Preservation Commitment leaves that roll back on a track and have a variable By Nathan Holth center of gravity during operation. Additionally, Chicago has been said to have more movable many of Chicago’s bascule bridges than any other city in the world. Many of these bridges are notable for bridges have historic significance. -

Historic Highway Bridges in Maryland: 1631-1960: Historic Context Report

HISTORIC HIGHWAY BRIDGES IN MARYLAND: 1631-1960: HISTORIC CONTEXT REPORT Prepared for: Maryland State Highway Administration Maryland State Department of Transportation 707 North Calvert Street Baltimore, Maryland 21202 Prepared by: P.A.C. Spero & Company 40 West Chesapeake Avenue, Suite 412 Baltimore, Maryland 21204 and Louis Berger & Associates 1001 East Broad Street, Suite 220 Richmond, Virginia 23219 July 1995 Revised October 1995 Acknowledgements "Historic Highway Bridges in Maryland: 1631-1960: Historic Context Report" has been prepared with the generous assistance of the Maryland Department of Transportation, State Highway Administration's Environmental Management Section and Bridge Development Division, and the historic and cultural resources staff of the Maryland Historical Trust. The preparers of this report would like to thank Cynthia Simpson, Rita Suffness, and Bruce Grey of the State Highway Administration Environmental Management Section, and Jim Gatley, Alonzo Corley, and Chris Barth of the State Highway Administration Bridge Development Division for their aid in providing access to key research materials. Thanks are also extended to Ron Andrews, Beth Hannold, Bill Pencek, Mary Louise de Sarran, and Barbara Shepard--all of the staff of the Maryland Historical Trust, and to the members of the Advisory Committee appointed to review this report. In addition we extend special appreciation to Rita Suffness, Architectural/Bridge Historian for the Maryland State Highway Administration, for providing us with numerous background materials, analyses, research papers, histories, and a draft historic bridge context report which she authored, for use in preparing this report. The final report was prepared by P.A.C. Spero & Company. Research, analysis, graphics preparation, and report writing were conducted by Paula Spero, Michael Reis, James DuSel, Kate Elliot, Laura Landefeld, and Deborah Scherkoske of P.A.C. -

Safety and Reliability of Bridge Structures

SAFETY AND RELIABILITY OF BRIDGE STRUCTURES Safety and Reliability of Bridge Structures Edited by Khaled M. Mahmoud Bridge Technology Consulting New York City, USA Front Cover: Kanchanaphisek Bridge, Samut Prakan Province, Thailand Photo courtesy of Parsons Brinckerhoff, USA Back Cover: (From top to bottom) Grimselsee Bridge, Bern, Switzerland Rendering courtesy of Christian Menn, Switzerland Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge, Kingston, New York, USA Photo courtesy of New York State Bridge Authority, USA Cover Design: Khaled M. Mahmoud Bridge Technology Consulting, New York City, USA CRC Press/Balkema is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, UK Typeset by Vikatan Publishing Solutions (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed and bound in the USA by Edwards Brothers, Inc, Lillington, NC All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publisher. Although all care is taken to ensure integrity and the quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the author for any damage to the property or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. Published by: CRC Press/Balkema P.O. Box 447, 2300 AK Leiden, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] www.crcpress.com – www.taylorandfrancis.co.uk – www.balkema.nl ISBN: 978-0-415-56484-7 (Hbk) ISBN: 978-0-203-86158-5 (Ebook) Table of contents Preface IX 1 Bridge safety, analysis and design The safety of bridges 3 T.V. -

SIA Occasional No4.Pdf

.. --;- 1840· MCMLXXXIV THE SOCIETY FOR INDUSllUAL ARCBE<LOGYpromotes the study of the physical survivals of our industrial heritage. It encourages and sponsors field investigations, research, recording, and the dissemination and exchange of information on all aspects of industrial archeology through publications, meetings, field trips, and other appropriate means. The SIA also seeks to educate the public, public agencies, and owners of sites on the advantages of preserving, through continued or adaptive use, structures and equipment of significance in the history of technology, engineering, and industry. A membership information brochure and a sample copy of the Society's newsletter are available on request. Society for Industrial Archeology Room 5020 National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC 20560 • Copyright 1984 by Victor C. Darnell All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without permission, in writing. from the author or the Society for Industrial Archeology. Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 84-51536 • Cover illustration: 'The above illustration is taken direct from a photograph and shows a square end view of a Parabolic Truss Bridge designed and built by us at Williamsport, Pa. The bridge is built across the Susquehanna River and consists of five spans of 200 ft. each with a roadway 18 ft. wide in the clear. Since the bridge was built a walk has been added on the north side. This is one of the longest iron high way bridges in the State of Pennsylvania and is built after our Patent Parabolic Form.' The bridge was built in 1885 and had a short life, being destroyed by flood in the 1890s. -

Bridge Companies

3 BRIDGE COMPANIES Luten Bridge Brochure Pages: Bridge companies such as Luten Bridge mailed or personally delivered brochures, pamphlets, and postcards to potential clients such as county or city governments in an effort to procure contracts. This image shows the frontispiece of a 1921, leather-bound, Luten promotional calendar and address book (Author’s Collection). The Luten Bridge Company was one of the most prolific builders of concrete arch bridges in Tennessee. The Harriman Bridge, a seven span closed spandrel arch built in 1918, is typical of Luten’s work (Author’s Collection). 152 BRIDGE COMPANIES BRIDGE COMPANIES In the early nineteenth century, local builders or engineers built most bridges. However, formal bridge companies began to appear in the mid-1800s. Although only a handful existed by 1870, from then until the end of the century, a plethora of companies flourished in the United States. In 1901 twenty-eight bridge and structural companies consolidated to form the American Bridge Company, becoming one of the largest bridge companies in the country. In 1902, American Bridge consolidated with nine other firms to form the United States Steel Corporation. Although a number of national and regional companies continued to operate, the heyday of experimentation and enterprising start-up companies effectively ended. In the 1910s, the federal review process for bridge construction and standardized bridge plans further changed the industry. Still, numerous bridge companies continued to provide structural steel and construction teams for highway projects until the Great Depression. In the 1930s, a combination of factors that included bank closures, the reduction in road and bridge construction, and changing trends in the field resulted in the demise of most of the bridge companies in the United States. -

Bulletin Summer 2017

VOLUME 46 NEWSLETTER SUMMER 2017 Downtown Bozeman 1875 GALLATIN MUSEUM photo Montana Ghost Town The Prez Sez TERRY HALDEN Quarterly The Montana Ghost Town Quarterly is published four times a year by the Convention 2017 in Bozeman is all set to go and it looks like Montana Ghost Town Preservation Society, it will be another winner. Margie Kankrik and Marilyn Murdock have P.O. Box 1861, Bozeman, Montana 59771. e-mail: [email protected] done a tremendous job in putting it together, along with some exciting www.mtghosttown.org guest speakers that are sure to inform and entertain you. Next year it Copyright © 2017, all rights reserved. is Darian Halden’s turn to put a convention together. I can assure Founded in 1970, the Montana Ghost Town you, from past experience, it is not an easy task. Preservation Society is a 501c3 non-profit organization dedicated to educating the public to In this issue of the newsletter, we welcome back Rachel the benefits of preserving the historic buildings, Phillips who has written an article about the Bozeman Hot Springs, sites, and artifacts that make up the living history of Montana. which is not as well-known as those hot springs between Butte and Opinions expressed in the bylined articles are Anaconda, but nevertheless, sports just as interesting a history. Your the authors’ and do not necessarily represent Vice-President, Brad O’Grosky has written an article about the history the views of the M. G. T. P. S. of bridges in Montana. Although they do not have the romance of SUMMER 2017 ghost towns, they were just as important to the development of Montana and as such their history should be maintained. -

Bridge Builders and Designers Active in Maryland the Following Companies and Individuals Are Known to Have Designed and Built Br

Bridge Builders and Designers Active in Maryland The following companies and individuals are known to have designed and built bridges in Maryland, based on documentary research alone. Descriptive information on each company or person was compiled from several sources, including prior historic resource survey data, historical research materials, lists provided by Rita Suffness of the Maryland State Highway Administration, prior bridge inventories performed in Pennsylvania and Delaware, and Victor Darnell's Directory of American Bridge Building Companies. A. and W. Denmead & Sons, Baltimore, Maryland This firm, located on the Canton waterfront of Baltimore, built bridges for Baltimore City during the 1850s. A. J. Boyle, Baltimore, Maryland This firm built SHA bridge 3010, US 1 over the Patapsco River, in 1915. American Bridge Company, Pittsburgh and Ambridge, Pennsylvania Founded in 1900, this massive bridge building company was the result of financier and U.S. Steel magnate J.P. Morgan's consolidation of twenty-eight formerly independent bridge companies, including several known to have marketed bridges in Maryland. In 1903, the American Bridge Company opened a huge new plant at Ambridge (Economy), Pennsylvania. Four additional companies, including the Toledo Bridge Company and the Virginia Bridge and Iron Company, were bought between 1901 and 1936. American Bridge Company is known to have fabricated or built numerous bridges for the State Roads Commission between the 1920s and the 1960s. Baltimore Bridge Company, Baltimore, Maryland Organized in 1869, this company was the direct successor to Smith, Latrobe and Company. The company was a major local competitor of Wendel Bollman's Patapsco Bridge Company and other Baltimore-based bridge building firms such as Campbell & Zell and H.A. -

Historic Iron & Steel Bridges

C. Historic context: Historic Iron and Steel Bridges in Minnesota, 1873-1945 NOTE: The original text of this context is included in “Iron and Steel Bridges in Minnesota,” National Register of Historic Places, Multiple Property Documentation Form, prepared by Fredric L. Quivik and Dale L. Martin, 1988, available in the Minnesota State Historic Preservation Office. Historic Iron and Steel Bridges in Minnesota, 1873-1945 Since its statehood in 1858, Minnesota has been reliant on bridges to maintain the effective transportation system needed to conduct commerce. The earliest bridges in the state were primarily wooden structures, but in the last quarter of the 19th century, iron and steel, materials which became available in large quantities as the United States industrialized, assumed the major role in carrying Minnesota's highways and railroads over rivers, streams, and other barriers. Iron was more common until the 1890s, when steel emerged as the preferred material. Although steel began to give way to reinforced concrete after 1910, it nevertheless, continued to play an important part in bridge building up to the present. This historic context will focus on iron and steel bridges in Minnesota from the time when the oldest surviving iron bridge in the state was built until the end of World War II, when the economy of the state and the nation moved into a new era. Before European-American fur traders arrived in Minnesota in the early 19th century, the region's transportation network consisted of the trails and water routes of the Indians. The U.S. government established a fort (now Fort Snelling) at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers in 1819, and nearby Mendota soon became a major fur-trading center. -

Kalispell 1/ \ Flathead County Montana HAER No. MI

Old Steel Bridge HAER No. MI'-21 Spann.mg the Flathead River on FAS 317,(1~ Miles East of) Kalispell 1/ \ tir! 1 Flathead County H Montana PHOI'CGRAPHS WRITI'EN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic Arrerican Engineermg Record National Park Service Departrrent of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Old Steel Bridge MT-21 Location: Spanning the Flathead River on FAS 317, 1-1/2 miles east of Kalispell, Flathead County, Montana. Date of Construction: 1894 Present Owner: Flathead County Flathead County Courthouse Kalispell, Montana 59901 Present Use: Vehicular Bridge Significance: Flathead County was created by the third session of the Montana legislature in 1893. Kalispell, which became the county seat, was becoming the important trade center for the northwest corner of the State. The mountain slopes of the county produced large quantities of lumber and the Flathead Valley, with rich soil, low elevation, and mild climate, was producing award-winning fruits and vegetables. A ~pur of the Great Northern RR served Kalispell. In January of 1894, the county commissioners decided to build a bridge over the Flathead River near the site of the Kalispell Ferry, provided the city of Kalispell would share the costs. In March, Gillette & Herzog of Minneapolis were awarded the contract for $17,497.00 with the county paying $9,999.000 and the city paying the remainder. The three main spans of the multi-span bridge are pin-connected Pratt through trusses, the southern-most being 220 feet long, the other two each being 144 feet long. The spans are approached.by wood stringer spans at each end and the total length of the bridge is 610 feet.