The Peru Power Grab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Bondage in Peru

CHINESE BONDAGE IN PERU Stewart UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES COLLEGE LIBRARV DUKE UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS CHINESE BONDAGE IN PERU Chinese Bondage IN PERU A History of the Chinese Coolie in Peru, 1849-1874 BY WATT STEWART DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1951 Copyright, 195 i, by the Duke University Press PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY THE SEEMAN PRINTERY, INC., DURHAM, N. C. ij To JORGE BASADRE Historian Scholar Friend Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/chinesebondageinOOstew FOREWORD THE CENTURY just passed has witnessed a great movement of the sons of China from their huge country to other portions of the globe. Hundreds of thousands have fanned out southwestward, southward, and southeastward into various parts of the Pacific world. Many thousands have moved eastward to Hawaii and be- yond to the mainland of North and South America. Other thousands have been borne to Panama and to Cuba. The movement was in part forced, or at least semi-forced. This movement was the consequence of, and it like- wise entailed, many problems of a social and economic nature, with added political aspects and implications. It was a movement of human beings which, while it has had superficial notice in various works, has not yet been ade- quately investigated. It is important enough to merit a full historical record, particularly as we are now in an era when international understanding is of such extreme mo- ment. The peoples of the world will better understand one another if the antecedents of present conditions are thoroughly and widely known. -

Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 7 Number 2 Pervuvian Trajectories of Sociocultural Article 13 Transformation December 2013 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Silva, Ernesto (2013) "Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol7/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emesto Silva Journal of Global Initiatives Volume 7, umber 2, 2012, pp. l83-197 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva 1 The aim of this essay is to provide a panoramic socio-historical overview of Peru by focusing on two periods: before and after independence from Spain. The approach emphasizes two cultural phenomena: how the indigenous peo ple related to the Conquistadors in forging a new society, as well as how im migration, particularly to Lima, has shaped contemporary Peru. This contribu tion also aims at providing a bibliographical resource to those who would like to conduct research on Peru. -

PERU REPUBLIC of Form 18-K Filed 2018-09-28

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 18-K Annual report for foreign governments and political subdivisions Filing Date: 2018-09-28 | Period of Report: 2017-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-18-286865 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER PERU REPUBLIC OF Mailing Address Business Address MINISTERIO DE ECONOMIA 241 EAST 49TH ST CIK:77694| IRS No.: 000000000 | Fiscal Year End: 1231 Y FINANZA NEW YORK NY 10017 Type: 18-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-02512 | Film No.: 181092999 JR JUNIN NO 319 SIC: 8888 Foreign governments LIMA PERU R5 999999999 Copyright © 2018 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 18-K ANNUAL REPORT of Republic of Peru (Name of Registrant) Date at end of last fiscal year: December 31, 2017 SECURITIES REGISTERED* (as of the close of the last fiscal year) CALCULATION OF REGISTRATION FEE Amounts as to Names of which registration exchanges on Title of Issue is effective which registered N/A N/A N/A Names and addresses of persons authorized to receive notices and communications from the Securities and Exchange Commission Ambassador Carlos Pareja Ríos Embassy of Peru 1700 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 (Name and address of Authorized Representative of the Registrant in the United States) Copies to: Jaime Mercado Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP 425 Lexington Avenue New York, New York 10017 Copyright © 2018 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document * The Registrant is filing this annual report on a voluntary basis. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

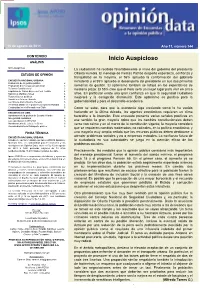

15 de agosto de 2011 Año 11, número 144 CONTENIDO Inicio Auspicioso ANÁLISIS Inicio Auspicioso 1 La ciudadanía ha recibido favorablemente el inicio del gobierno del presidente ESTUDIO DE OPINIÓN Ollanta Humala. El mensaje de Fiestas Patrias despertó esperanza, confianza y tranquilidad en la mayoría, el 56% aprueba la conformación del gabinete ENCUESTA NACIONAL URBANA ministerial y el 55% aprueba el desempeño del presidente en sus dos primeras Evaluación de la gestión pública 2 Evaluación del mensaje presidencial 3 semanas de gestión. El optimismo también se refleja en las expectativas de Reforma Constitucional 3 mediano plazo: El 55% cree que el Perú será un mejor lugar para vivir en cinco Expulsión de Carlos Bruce de Perú Posible 4 Sanción a Martha Chávez 4 años. En particular existe una gran confianza en que la seguridad ciudadana Futuros líderes políticos 4 mejorará y la corrupción disminuirá. Este optimismo es positivo para la Amnistía a Antauro Humala 5 La Primera Dama Nadine Heredia 5 gobernabilidad y para el desarrollo económico. Presencia Militar en el gobierno de Ollanta Humala 5 Continuidad en el diferendo con Chile 5 Como se sabe, para que la economía siga creciendo como lo ha venido ENCUESTA EN LIMA haciendo en la última década, los agentes económicos requieren un clima Aprobación de la gestión de Susana Villarán 5 favorable a la inversión. Esta encuesta presenta varias señales positivas en Inseguridad ciudadana 6 La reapertura del el Frontón 6 ese sentido: la gran mayoría opina que los cambios constitucionales deben Nombramiento de Jefa de la Sunat 6 verse con calma y en el marco de la constitución vigente; la mayoría considera Reordenamiento del transporte público 6 que se requieren cambios moderados, no radicales, en la política económica; y FICHA TÉCNICA una mayoría muy amplia señala que los recursos públicos deben destinarse a ENCUESTA NACIONAL URBANA atender problemas sociales y no a empresas estatales. -

Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon Christian Calienes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2526 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 CHRISTIAN CALIENES All Rights Reserved ii The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon by Christian Calienes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Earth & Environmental Sciences in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Inés Miyares Chair of Examining Committee Date Cindi Katz Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Inés Miyares Thomas Angotti Mark Ungar THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes Advisor: Inés Miyares The resistance movement that resulted in the Baguazo in the northern Peruvian Amazon in 2009 was the culmination of a series of social, economic, political and spatial processes that reflected the Peruvian nation’s engagement with global capitalism and democratic consolidation after decades of crippling instability and chaos. -

Ideólogos Y Expertos En El Perú Reciente

Ideólogos y expertos en el Perú reciente Juan Martín Sánchez* y Osmar Gonzales** Escuela deEstudios Hispano-Americanos, CSIC. Sevilla y Biblioteca Nacional de Perú En este artículo se contraponen las figuras del ideólogo y el experto que tienen en común el uso del conocimiento y su polémica proximidad a las altas esferas del gobierno estatal. Se esbozan tres decenios de la vida política peruana en que aparecen y desaparecen esas dos figuras, atendiendo a su extracción sociopolítica y a su lugar en las luchas dentro del poder estatal. El movimiento pendular que parecieran haber tenido en las décadas de los setenta y ochenta, entre gobiernos reformistas más ambi- ciosos en cuanto a producción ideológica y los gobiernos conservadores más pragmá- ticos, se rompe con la irrupción del gobierno de Fujimori con sus tácticas mafiosas y secretas. En las últimas décadas y a escala mundial el llamado experto o tec- nócrata ha adquirido una importancia creciente hasta el punto de poner en tensión los clásicos modelos ilustrados de la política. Si bien su presencia no es absolutamente inédita sí lo es su arrollador protagonismo, siempre asido a las altas esferas del poder, ligado a las instancias últimas de deci- sión. En un proceso paulatino, el experto ha ido desplazando a ese tipo de intelectual tan cautivante y polémico como es el ideólogo. Éste, atento a los grandes valores que supuestamente deben tutelar a las sociedades, defien- de proyectos de formación de comunidad, preocupación que para los exper- tos resulta irrelevante. Desde los años del reformismo militar dirigido por el general Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968-1975), hasta el autoritarismo tecno-militar acaudi- llado por el ingeniero Alberto Fujimori, pasando por la fase conservadora del gobierno militar (comandada por el general Francisco Morales Bermúdez, 1975-1980) y los dos gobiernos constitucionales de la década del ochenta (de Acción Popular, 1980-1985, y el de APRA, 1985-1990), la tensión entre humanistas y expertos por capturar las fantasías del Príncipe ha sido perma- nente. -

1 Período Legislativo 2011 Período

Estamos para servirlo de lunes a viernes de 09:00 a 17:00 horas. Jr. Junín s/n cuadra 5. Teléfono 311-7777 anexos 5152- 5153 - 5154 (fax) http://www.congreso.gob.pe E-mail: di [email protected] PERÍODO LEGISLATIVO 20112011----20122012 COMISIÓN PERMANENTE 3.ª SESIÓN (Vespertina) VIERNES 7 DE OCTUBRE DE 2011 PRESIDENCIA DEL SEÑOR DANIEL ABUGATTÁS MAJLUF SUMARIO Se pasa lista.lista.———— Se abre la sesión.sesión.———— Se aprueba, sin observaciones, el acta de la 2.ª Sesión, celebrada el día 14 de setiembre de 2011.2011.———— Se aprueba el proyecto de resolución legislativa que ratifica la designación del señor Julio Emilio VelarVelardede Flores como presidente del Directorio del Banco Central de Reserva del Perú.Perú.———— Se acuerda la designación de los congresistas María Soledad Pérez Tello y Víctor Andrés García Belaunde como integrantes de la Subcomisión de Acusaciones Constitucionales para el período anual de sesiones 20112011----20122012 en reemplazo de los señores Luis Iberico NúñezNúñez y Rennán Espinoza Rosales, respectivamente.respectivamente.———— Se acuerda la designación del señor Víctor Andrés García Belaunde como presidente de la SubcomisiónSubcomisión de Acusaciones ConstitucConstitucionalesionales para el período anual de sesiones 20112011----2012.2012.2012.———— Se levanta la sesión. —A las 12 horas y 14 minutos, bajo la Presidencia del señor Daniel Abugattás Majluf e integrando la Mesa Directiva los señores Manuel Merino de Lama y Yehude Simon Munaro, el Relator pasa lista, a la que contestan los señores congresistas Miguel Grau Seminario 111, Delgado Zegarra, Chehade Moya, Solórzano Flores, Mavila León, Otárola 1 Por Res. Leg. N.° 23680 (13-10-83), se dispone permanentemente una curul, en el Hemiciclo del Congreso, con el nombre del Diputado Miguel Grau Seminario. -

Corruption and Anti-Corruption Agencies: Assessing Peruvian Agencies' Effectiveness

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2020 Corruption and Anti-corruption Agencies: Assessing Peruvian Agencies' Effectiveness Kia R. Del Solar University of Central Florida Part of the Political Science Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Del Solar, Kia R., "Corruption and Anti-corruption Agencies: Assessing Peruvian Agencies' Effectiveness" (2020). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 698. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/698 CORRUPTION AND ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES: ASSESSING PERUVIAN AGENCIES’ EFFECTIVENESS by KIA DEL SOLAR PATIÑO A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Majors Program in Political Science in the School of Politics, Security, and International Affairs and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2020 Thesis Chair: Bruce Wilson, Ph.D. Abstract Corruption has gained attention around the world as a prominent issue. This is because corruption has greatly affected several countries. Following the exploration of various definitions and types of corruption, this thesis focuses on two efforts to rein in “grand corruption”, also known as executive corruption. The thesis is informed by existing theories of corruption as well as anti- corruption agencies and then situates Peru’s experience with corruption in its theoretical context and its broader Latin American context. -

Políticas Públicas, Pandemia Y Corrupción: El Caso “Vacunagate” En Perú

984 POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS, PANDEMIA Y CORRUPCIÓN: EL CASO “VACUNAGATE” EN PERÚ PUBLIC POLICIES, PANDEMIC AND CORRUPTION: THE “VACUNAGATE” CASE IN PERU Recebido em: 04/02/2021 Aprovado em: 02/04/2021 Manuel Bermúdez-Tapia 1 RESUMEN En el período de marzo a octubre del 2021, La presidencia de la República del Perú a cargo de Martín Vizcarra Cornejo había desarrollado una serie de políticas públicas que procuraban atender la pandemia del Covid-19, entre ellas un proceso que involucraba la búsqueda y adquisición de vacunas contra el virus que había dejado al país en una situación de calamidad nacional. A la salida del gobierno, las indagaciones preliminares habían determinado que la negociación y adquisición de vacunas involucraba una serie de actos que podrían generar 1 Abogado graduado con la mención de Summa Cumme Laude por la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Magister en Derecho, Doctorado en Derecho en la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Argentina. Profesor Investigador de la Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista y profesor de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Investigador afiliado al MinCiencias de Colombia y al RENACYT de Perú, con código PO140233, ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1576-9464. Correo electrónico: [email protected] R E V I S T A D I R E I T O S S O C I A I S E P O L Í T I C A S P Ú B L I C A S (UNIFAFIBE) D ISPONÍVEL EM : WWW. UNIFAFIBE . COM . BR/ REVISTA / INDEX . PHP / DIREITOS - SOCIAIS - POLITICAS - PUB / INDEX ISSN 2 3 18 -5 73 2 – V OL. -

Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori's Extradition Process

Law and Business Review of the Americas Volume 14 Number 3 Article 8 2008 Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori's Extradition Process Patricio Noboa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/lbra Recommended Citation Patricio Noboa, Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori's Extradition Process, 14 LAW & BUS. REV. AM. 621 (2008) https://scholar.smu.edu/lbra/vol14/iss3/8 This Comment and Case Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law and Business Review of the Americas by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. FORMER PERUVIAN PRESIDENT ALBERTO FUJIMORI'S EXTRADITION PROCESS Patricio Noboa* I. INTRODUCTION "gAlguna duda, ingeniero? ZMe van a enmarrocar?... No, eso no ocurrird" ATURDAY, September 22 of 2007, 5:12 p.m., Peruvian time. After seven years of exile, Alberto Fujimori, Peru's strongman president from 1990 to 2000, returns to Peru. 2 This historical event takes place one day after the Chilean Supreme Court's long-anticipated deci- sion granting the Peruvian government's request to extradite Mr. Fujimori so that he can be prosecuted in Peru for claims of crimes against humanity and corruption, which allegedly took place during his time in office.3 Former President Fujimori's controversial career is an issue that has divided the Peruvian opinion. To his supporters, Mr. Fujimori is the man who saved Peru "from the twin evils of terrorism and economic col- lapse."'4 Thus, he is remembered with gratitude by some of the Peruvian population for "crush[ing] the Shining Path guerrillas, stabili[zing] the economy' 5 by overcoming hyperinflation, and "buil[ding] schools and *Patricio Noboa received his Bachelor in Law from the School of Law and Political Science at the University of Lima in Lima, Peru, and his Masters of Law in Com- parative and International Law from the Dedman School of Law at Southern Methodist University. -

El Otro Virus Que Mata En El Perú: La Corrupción En Tiempos De Pandemia

El otro virus que mata en el Perú: la corrupción en tiempos de pandemia The other virus that kills in Peru: corruption in times of pandemic Delcy Ruiz-Enriquez Universidad César Vallejo - Perú [email protected] Carlos Jaime Gonzales-Castilla Universidad César Vallejo - Perú [email protected] Cristian Gumercindo Medina-Sotelo Universidad César Vallejo - Perú [email protected] doi.org/10.33386/593dp.2021.3.581 V6-N3 (may-jun) 2021, pp. 452-464 | Recibido: 30 de marzo de 2021 - Aceptado: 29 de abril de 2021 (2 ronda rev.) 452 RESUMEN El coronavirus (Covid-19) ha causado una profunda crisis mundial. El Perú no ha sido ajeno a esta crisis, dado que, según reporte de la sala situacional del Ministerio de Salud, tenemos 1´520,973 contagiados y 51,238 muertes hasta el 28 de marzo del 2021. La pandemia viene evidenciando profundas carencias del país, las mismas que han sido desatendidas por décadas, a pesar del crecimiento económico vivido, como es el caso los servicios básicos, la alta informalidad que debilita las bases de la sociedad peruana, y lo más grave, la ineficiencia, indiferencia y corrupción del aparato público, que han continuado aún en plena pandemia, desestabilizando cualquier iniciativa de cambio y de buenas intenciones por recuperar la confianza y legitimidad ciudadana. El propósito del artículo es dar cuenta del drama peruano de la corrupción en plena pandemia del Covd-19, para ello se analizó la bibliografía disponible, haciendo uso de plataformas virtuales, que permitieron acceder a la información objeto de estudio. Las principales conclusiones a los que arriba la investigación es que es necesario abordar por igual al coronavirus y a la corrupción, revalorando los servicios básicos en la sociedad y fortaleciendo la participación ciudadana, como mecanismo de vigilancia y control. -

A Construçao Do Conhecimento

MAPAS E ICONOGRAFIA DOS SÉCS. XVI E XVII 1369 [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] Apêndices A armada de António de Abreu reconhece as ilhas de Amboino e Banda, 1511 Francisco Serrão reconhece Ternate (Molucas do Norte), 1511 Primeiras missões portuguesas ao Sião e a Pegu, 1. Cronologias 1511-1512 Jorge Álvares atinge o estuário do “rio das Pérolas” a bordo de um junco chinês, Junho I. Cronologia essencial da corrida de 1513 dos europeus para o Extremo Vasco Núñez de Balboa chega ao Oceano Oriente, 1474-1641 Pacífico, Setembro de 1513 As acções associadas de modo directo à Os portugueses reconhecem as costas do China a sombreado. Guangdong, 1514 Afonso de Albuquerque impõe a soberania Paolo Toscanelli propõe a Portugal plano para portuguesa em Ormuz e domina o Golfo atingir o Japão e a China pelo Ocidente, 1574 Pérsico, 1515 Diogo Cão navega para além do cabo de Santa Os portugueses começam a frequentar Solor e Maria (13º 23’ lat. S) e crê encontrar-se às Timor, 1515 portas do Índico, 1482-1484 Missão de Fernão Peres de Andrade a Pêro da Covilhã parte para a Índia via Cantão, levando a embaixada de Tomé Pires Alexandria para saber das rotas e locais de à China, 1517 comércio do Índico, 1487 Fracasso da embaixada de Tomé Pires; os Bartolomeu Dias dobra o cabo da Boa portugueses são proibidos de frequentar os Esperança, 1488 portos chineses; estabelecimento do comércio Cristóvão Colombo atinge as Antilhas e crê luso ilícito no Fujian e Zhejiang, 1521 encontrar-se nos confins