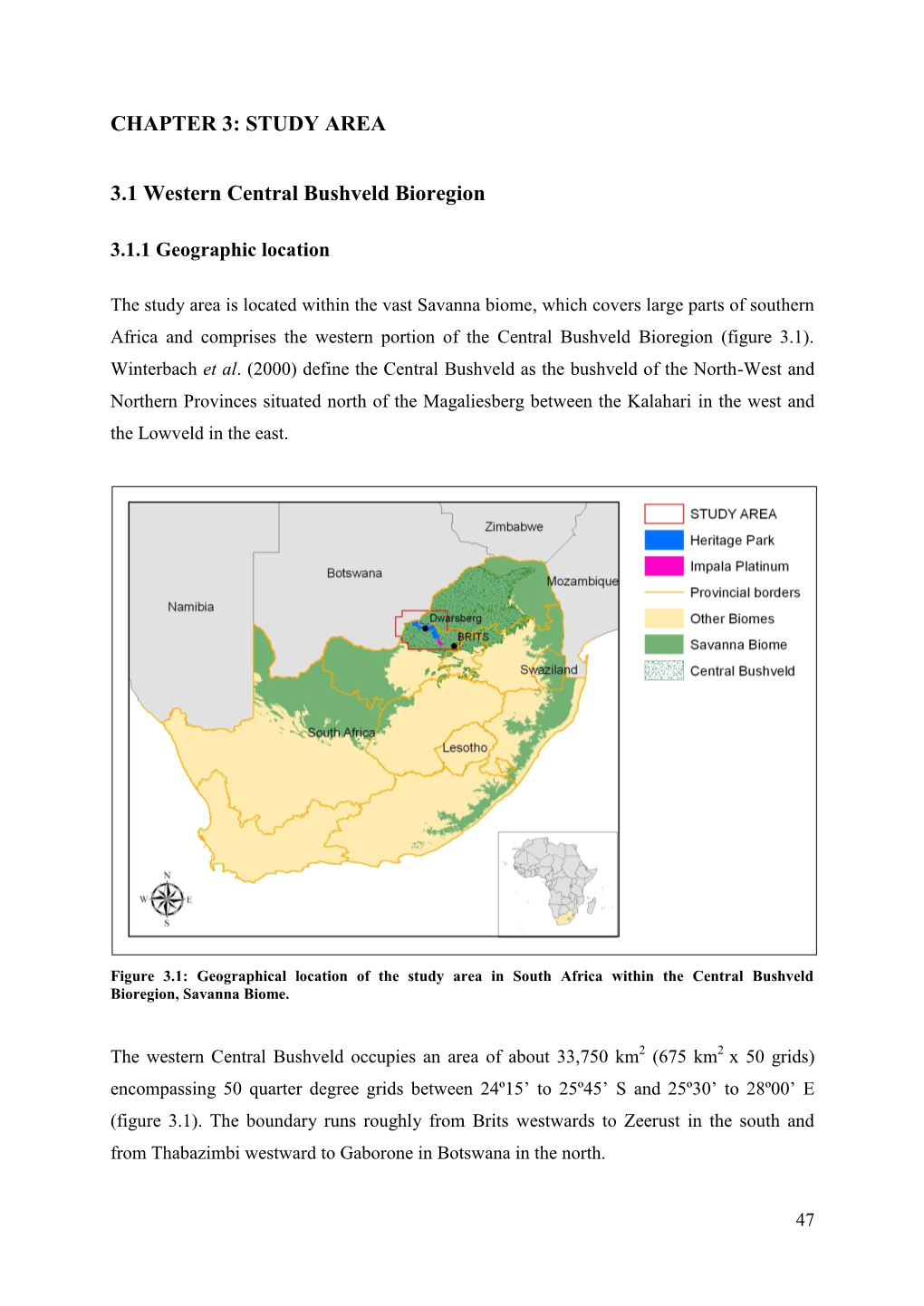

CHAPTER 3: STUDY AREA 3.1 Western Central Bushveld Bioregion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KEIDEL Itinerary

GILDEA, KEIDEL AND SCHULTZ ITINERARY SOUTH AFRICA - DECEMBER 2014 DAY BY DAY DAY 1 (SUNDAY 7 DECEMBER) Pick up your rental car and head towards Lesedi Cultural Village. Your accommodation on the 6th had not been confirmed yet, but more than likely the fire and ice hotel in Melrose Arch, in which case the following directions are suitable. From Johannesburg take the M1 north towards Pretoria, (the highway right next to Melrose Arch) and then turn west onto the N1 at the Woodmead interchange, following signs to Bloemfontein (Roughly 10km after you get onto the highway). At the Malabongwe drive off-ramp (roughly another 10 km), turn off and then turn right onto Malabongwe drive (R512), proceed for 40 kms along the R512, Lesedi is clearly marked on the left-hand side of the rd. The Lesedi Staff will meet you on arrival. Start your journey at the Ndebele village with an introduction to the cultural experience preceded by a multi-media presentation on the history and origins of South Africa’s rainbow nation. Then, enjoy a guided tour of the other four ethnic homesteads – Zulu, Basotho, Xhosa and Pedi. As the sun sets over the African bush, visit the Boma for a very interactive affair of traditional singing and dancing, which depict stories dating back to the days of their ancestors. Dine in the Nyama Choma Restaurant, featuring ethnic dishes, a fusion of Pan African cuisine all complemented by warm, traditional service. Lesedi African Lodge and Cultural Village Kalkheuwel, Broederstroom R512, Lanseria, 1748 [t] 087 940 9933 [m] 071 507 1447 DAY 2 – 4 (MONDAY 8 DECEMBER – WEDNESDAY 10 DECEMBER) After a good night’s sleep awaken to the sounds of traditional maskande guitar or squash-box, and enjoy a full English breakfast, which is served in the restaurant. -

North West No Fee Schools 2020

NORTH WEST NO FEE SCHOOLS 2020 NATIONAL EMIS NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER NUMBER 2020 NUMBERS 2020 600100023 AMALIA PUBLIC PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. BOX 7 AMALIA 2786 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 1363 600100033 ATAMELANG PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. BOX 282 PAMPIERSTAD 8566 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 251 600100036 AVONDSTER PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. BOX 335 SCHWEIZER-RENEKE 2780 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 171 600100040 BABUSENG PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O. BOX 100 LERATO 2880 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 432 600100045 BADUMEDI SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY P. O. BOX 69 RADIUM 0483 BOJANALA 1 591 600100049 BAGAMAIDI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O BOX 297 HARTSWATER 8570 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 247 600103614 BAHENTSWE PRIMARY P.O BOX 545 DELAREYVILLE 2770 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 119 600100053 BAISITSE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O. BOX 5006 TAUNG 8584 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 535 600100056 BAITSHOKI HIGH SCHOOL SECONDARY PRIVATE BAG X 21 ITSOSENG 2744 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 774 600100061 BAKGOFA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P O BOX 1194 SUN CITY 0316 BOJANALA 1 680 600100067 BALESENG PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P. O. BOX 6 LEBOTLOANE 0411 BOJANALA 1 232 600100069 BANABAKAE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P.O. BOX 192 LERATO 2880 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 740 600100071 BANCHO PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY PRIVATE BAG X10003 MOROKWENG 8614 DR RUTH S MOMPATI 1 60 600100073 BANOGENG MIDDLE SCHOOL SECONDARY PRIVATE BAG X 28 ITSOSENG 2744 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA 1 84 600100075 BAPHALANE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY P. O. BOX 108 RAMOKOKASTAD 0195 BOJANALA 1 459 600100281 BARETSE PRIMARY PRIMARY P.O. -

Genetic Verification of Multiple Paternity in Two Free-Ranging Isolated Populations of African Wild Dogs (Lycaon Pictus)

University of Pretoria etd – Moueix, C H M (2006) Genetic verification of multiple paternity in two free-ranging isolated populations of African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) by Charlotte Moueix Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Production Animal Studies Faculty of Veterinary Science University of Pretoria Onderstepoort Supervisor Prof HJ Bertschinger Co-supervisors Dr CK Harper Dr ML Schulman August 2006 University of Pretoria etd – Moueix, C H M (2006) DECLARATION I, Charlotte Moueix, do hereby declare that the research presented in this dissertation, was conceived and executed by myself, and apart from the normal guidance from my supervisor, I have received no assistance. Neither the substance, nor any part of this dissertation has been submitted in the past, or is to be submitted for a degree at this University or any other University. This dissertation is presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MSc in Production Animal Studies. I hereby grant the University of Pretoria free license to reproduce this dissertation in part or as whole, for the purpose of research or continuing education. Signed ……………………………. Charlotte Moueix Date ………………………………. ii University of Pretoria etd – Moueix, C H M (2006) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have been lucky to have people at my side whose support, encouragement and wisdom made all the difference. The following people and organisations contributed to the completion of this work, either materially or through their expertise or moral support: Prof. Henk Bertschinger, for trusting me with this project and making it possible. Dr. Martin Schulman, for his expert advice. -

THE PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION of an 88Kv DISTRIBUTION POWERLINE from the EXISTING STRAATSDRIFT SUBSTATION to the PROPOSED SILWERKRAA

THE PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF AN 88kV DISTRIBUTION POWERLINE FROM THE EXISTING STRAATSDRIFT SUBSTATION TO THE PROPOSED SILWERKRAANS SUBSTATION WITHIN THE RAMOTSHERE MOILOA, MOSES KOTANE AND KGETLENGRIVIER LOCAL MUNICIPALITIES, NORTH WEST PROVINCE Ecological & Avifauna Component June 2017 Compiled by: Prepared for: Pachnoda Consulting CC Baagi Environmental Consultancy Lukas Niemand Pr.Sci.Nat PostNet Suite 412 PO Box 72847 Private Bag x4 Lynwood Ridge MENLO PARK Pretoria 0102 0040 Pachnoda Consulting cc Straatsdrift - Silwerkraans 88kV powerline EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Pachnoda Consulting CC was contracted by Baagi Environmental Consultancy CC to provide a terrestrial ecological report (general ecology and avifauna) for the proposed construction of an 88 kV distribution powerline from the existing Straatsdrift substation to the proposed Silwerkraans substation within the Ramotshere Moiloa, Moses Kotane and Kgetlengrivier Local Municipalities, North West Province. The project consists of two proposed corridors: Preferred Corridor (47.2 km) on the eastern section of the study area; and Alternative Corridor (45.8 km) on the western section of the study area. The terms of reference for this assessment are to: provide a general description of the affected environment concerning the avifaunal and terrestrial habitat types; conduct an assessment of all available information in order to present the following results: o typify the regional and local vegetation that will be affected by the proposed corridors; o provide an indication on the occurrence of threatened, “near- threatened”, endemic and conservation important plant, bird or animal species likely to be affected by the proposed corridors; o provide an indication of sensitive bird, fauna habitat and vegetation corresponding to the proposed corridors; o highlight areas of concern or hotspot areas; o identify potential impacts on the terrestrial ecological environment that are considered pertinent to the proposed development; o identify negative impacts and feasible mitigation options. -

Moses Kotane Local Municipality

Moses Kotane Local Municipality Final IDP/Budget for the Financial Year 2017/2022 4th Generation IDP Page 1 of 327 Table of Content HEADINGS PAGES SECTION A Part One 1. Mayor’s Foreword……………………………………………………………………………………. 7 – 8 2. Municipal Manager’s foreword…………………………………………………………………….. 9 – 10 Part Two 3. Introduction and Legislative Requirements…………..…………………………………….……. 12 – 14 4. Service Delivery and Budget Imlementation Plan: Progress for the last Five Years…...… 14 5. IDP/PMS/Budget Process Plan 2017/2018………………………………………………………... 15 – 16 5.1 Where are we and Where to (Vision, Mission and Values)………….……………………… 17 5.2 Municipal Vision Statement…………………………………………………………………….. 17 5.3 The Proposed Vision…………………………………………………………………………….. 17 5.4 Proposed Mission………………………………………………………………………………... 17 5.5 Municipal Values…………………………………………………………………………………. 18 5.6 Municipal Priorities…………………………………………………………………………….… 18 5.7 IDP Developmental Processes…………………………………………………………………. 19 5.8 Key Components of the IDP Processes……………………………………………………….. 20 – 29 Part Three 6. Analysis Phase 6.1 Local Orientation ………………………………………………………………………………… 30 6.2 Demographic Profile……………………………………………………………………………... 31 6.3 Racial Composition………………………………………………………………………………. 31 6.4 Ward Level Population by Age Group and Gender………………………………………….. 31 – 33 6.5 Household per ward........................................................................................................... 33 – 34 6.6 Population Distribution/composition structure and pyramid…………………………………. 32 – 33 6.7 National Mortality, -

Recueil Des Colis Postaux En Ligne SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE

Recueil des colis postaux en ligne ZA - South Africa SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE LIMITED ZAA Service de base RESDES Informations sur la réception des Oui V 1.1 dépêches (réponse à un message 1 Limite de poids maximale PREDES) (poste de destination) 1.1 Colis de surface (kg) 30 5.1.5 Prêt à commencer à transmettre des Oui données aux partenaires qui le veulent 1.2 Colis-avion (kg) 30 5.1.6 Autres données transmis 2 Dimensions maximales admises PRECON Préavis d'expédition d'un envoi Oui 2.1 Colis de surface international (poste d'origine) 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non RESCON Réponse à un message PRECON Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus (poste de destination) grand pourtour) CARDIT Documents de transport international Oui 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non pour le transporteur (poste d'origine) (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus RESDIT Réponse à un message CARDIT (poste Oui grand pourtour) de destination) 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui 6 Distribution à domicile (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus grand pourtour) 6.1 Première tentative de distribution Oui 2.2 Colis-avion effectuée à l'adresse physique du destinataire 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non 6.2 En cas d'échec, un avis de passage est Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus laissé au destinataire grand pourtour) 6.3 Destinataire peut payer les taxes ou Non 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non droits dus et prendre physiquement (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus livraison de l'envoi grand pourtour) 6.4 Il y a des restrictions gouvernementales 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui ou légales vous limitent dans la (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus prestation du service de livraison à grand pourtour) domicile. -

Annual Report 2016-2017

Department: Public Works and Roads North West Provincial Government Republic of South Africa ANNUAL REPORT 201 6-20 17 "$& & $ !$&! 6A2CE>6?E@7%F3=:4,@C<D2?5'@25D %C@G:?4:2=625$77:46 #82<2"@5:C:"@=6>2'@25 ">232E9@ %C:G2E628- ">232E9@ )6= O ,63D:E6HHH?HA88@GK2 AF3=:4H@C<D Annual Report 2016/17 1 PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION . .6 1. FOREWORD BY THE MEC . .8 2. REPORT OF THE ACCOUNTING OFFICER . .9 3. STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY AND CONFIRMATION OF THE ACCURACY OF THE ANNUAL REPORT . .12 4. STRATEGIC OVERVIEW . .13 5. LEGISLATIVE AND OTHER MANDATES . .13 5.1 Legislative mandates . .13 5.2 Policy mandates . .14 6. ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE . .20 7. ENTITIES REPORTING TO THE MEC . .22 PART B: PERFORMANCE INFORMATION . .23 8. AUDITOR GENERAL’S REPORT: PRE-DETERMINED OBJECTIVES . .24 9. OVERVIEW OF DEPARTMENTAL PERFORMANCE . .24 9.1 Service Delivery Environment . .24 9.2 Service Delivery Improvement Plan . .32 9.3 Organizational Environment . .36 9.4 Key policy developments and legislative changes . .36 10. STRATEGIC OUTCOME-ORIENTED GOALS . .37 11. PERFORMANCE INFORMATION BY PROGRRAMME . .37 11.1 Programme 1: Administration . .37 11.2 Programme 2: Public Works Infrastructure . .39 11.3 Programme 3: Transport Infrastructure . .43 11.4 Programme 4: Community-Based Programme . .45 12. TRANSFER PAYMENTS . .48 13. CONDITIONAL GRANTS . .48 14. DONOR FUNDS RECEIVED . .49 15. CAPITAL INVESTMENT . .50 Annual Report 2016/17 2 PART C: GOVERNANCE . .59 16. GOVERNANCE IN THE DEPARTMENT . .60 16.1 Risk Management . .61 16.2 Fraud and Corruption . .61 16.3 Minimizing conflict of interest . -

Annual Performance Plan 2019 - 2022 MTEF

Performance Plan Title of Publication: North West Province Department of Public Works and Roads Annual Performance Plan 2019 - 2022 MTEF Department of Public Works and Roads Provincial Head Office Ngaka Modiri Molema Road Mmabatho 2735 Private Bag X2080 Mmabatho 2735 Tel. (018) 3881450/3881366 Website: www.nwpg.gov.za/publicworks 1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS APP Annual Performance Plan CIDB Construction Industry Development Board COIDA Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act DBAC Departmental Bid Adjudication Committee DORA Division of Revenue Act DPSA Department of Public Service and Administration DPW&R Department of Public Works and Roads EPWP Expanded Public Works Programme FTE Full Time Equivalent GIAMA Government Immovable Asset Management Act GITC GIAMA Implementation Technical Committee HOD Head of Department HR Human Resources IAR Immovable Asset Register ICT Information and Communication Technology IDIP Infrastructure Delivery Improvement Programme IDMS Infrastructure Delivery Management System IPIP Infrastructure Programme Implementation Plan IPMP Infrastructure Programme Management Plan KPA Key Performance Area MEC Member of Executive Council MPAT Management Performance Assessment Tool MPSA Minister of Public Service and Administration MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework MTSF Medium Term Strategic Framework NDP National Development Plan NDPW National Department of Public Works NDRDLR National Department of Rural Development and Land Reform NGO Non-governmental Organization PFMA Public Finance Management Act 2 -

Madikwe Hills Private Game Reserve I North-West Province

MADIKWE HILLS PRIVATE GAME RESERVE I NORTH-WEST PROVINCE www.madikwehills.com AUGUST 2013 Moscow London Frankfurt Paris Milan Rome Doha Dubai BOTSWANA DERDEPOORT GATE ZAMBIA Singapore AFRICA Seychelles TAU VICTORIA GATE FALLS ZIMBABWE Johannesburg Gaberone Marico River MADIKWE HILLS BOTSWANA Kruger MADIKWE National WONDERBOOM Park GATE GAME Timbavati GR TUNINGI GABORONE Sabi Sands GR MOZAMBIQUE RESERVE Madikwe GR Pilanesburg GR Hazyview Sun City PRETORIA White River ABJATERSKOP Johannesburg PILANESBERG GATE MOLATEDI GATE GAME RESERVE Dwarsberg/ Mabeskraal NORTH WEST Molatedi Dam ZEERUST SOUTH AFRICA August 2012 ATLANTIC OCEAN INDIAN SOUTH AFRICA OCEAN George CAPE TOWN Knysna Port Elizabeth BOMA GYM KITCHEN TSALA 1 MAIN DINING RECEPTION & ROOM MAIN OFFICE & BAR CURIO & RANGER OFFICE 2 8 WATERHOLE 5 7 6 3 4 9 10 11 12 LITTLE MADIKWE Traversing over 75 000 hectares, Madikwe Hills Private Game Lodge is situated on a hill, in the heart of the malaria-free Madikwe Game Reserve. Ingeniously set amongst boulders and age-old Tamboti trees, the lodge offers visitors the utmost in luxury and hospitality, where you will find yourself enchanted by a world of intrigue and majestic beauty. LOCATION • Madikwe Game Reserve – North West Province. • 4½ hours from Johannesburg/Pretoria. ACCOMMODATION MAIN CAMP • 10 Secluded glass fronted suites (±150m2) • Uninterrupted views of the African bush • Private deck with plunge pool • Air-conditioning • Fans • Fireplaces • Fully stocked mini-bar • Indoor and outdoor showers • Mosquito nets • Private lounge ACCOMMODATION LITTLE MADIKWE (Family Friendly Camp) Little Madikwe comprises of a 2 Bedroomed Suite (±390m2). An additional 2 Luxury Suites (±150m2) can be reserved to form a completely private camp accommodating up to 8 guests. -

Directions from Tuningi to Sun City

BOTSWANA GABORONE MADIKWE GAME WONDERBOOM RESERVE GATE Molatedi Dam ABJATERSKOP GATE Dwarsberg MOLATEDI GATE DRIVING DIRECTIONS A1 R49 Mabeskraal PILANESBERG FROM TUNINGI TO SUN CITY Zeerust NATIONAL PARK N4 Groot Marico Sun City Hartbeespoort Rustenburg N4 PRETORIA N1 DIRECTIONS FROM TUNINGI SAFARI LODGE TO SUN CITY [VIA MOLATEDI GATE] THE GRAVEL ROAD ON THIS ROUTE MAKES IT A LITTLE BUMPY BUT NOT IMPASSABLE IN A SEDAN VEHICLE. JOHANNESBURG THE ESTIMATES DRIVING TIME IS 2 TO 2½ HOURS. • From Tuningi Safari Lodge exit the lodge and turn right at the first road. • Follow this road and turn left at the T- junction. • Continue past Rhulani Safari Lodge and turn right at the T- junction. • Continue past Royal Madikwe and Impodimo Lodge and turn left at the T – junction towards Wonderboom Gate. • Exit Wonderboom Gate and turn left on the R49 towards Zeerust. • Continue along this road for 7km’s and turn left in to Abjaterskop Gate to re-enter Madikwe. • After entering Abjaterskop gate continue along this road passing the Western Airstrip. • Follow the road till you reach a T-junction with signboard for Molatedi Gate and Derdepoort gate. • Turn left towards Molatedi Gate • Follow this road till the next signboard and turn right towards Molatedi Gate. • Follow this road for 11km’s and exit Madikwe at Molatedi gate. • After exiting Molatedi gate follow the gravel road for 32km’s, it then becomes tar continue straight for another 26km’s into Mabeskraal. • In Mabeskraal turn left at the 4 way stop with signboard stating Sun City. • Follow this road for 34.8km’s and turn right at the T- junction with signboard stating Sun City. -

Peasants and Politics in the Western Transvaal, 1920-1940

PEASANTS AND POLITICS IN THE WESTERN TRANSVAAL, 1920-1940 G.N. SIMPSON PEASANTS AND POLITICS IN THE WESTERN TRANSVAAL, 1920-1940 Graeme Neil Simpson A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. Johannesburg 1986 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other University Graeme Neil Simpson 5 August 1986 ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the political and ideological struggles within Tswana chiefdoms in the Rustenburg district of the Western Transvaal in the period 1920 - 1940. This period was characterized by a spate of struggles against tribal chiefs which took on similar forms in most of the chiefdoms of the district. These challenges to chiefly political authority reflected a variety of underlying material interests which were rooted in the process of class formation resulting from the development of capitalist relations of production within the wider society. Despite the variations in material conditions in the different chiefdoms of the district, the forms of political and ideological resistance were very similar. The thesis examines the extent of the influences of Christian missions and national political organisations in these localized struggles, and also explores the relationship between chiefs, Native Affairs Department officials and the rural African population in the context of developing segregationalist ideology during the inter-war period. iii PREFACE This thesis was originally born out of a desire to extend and expand on the research which I did in the course of my B.A. -

Provincial-Gazette-ZA-NW-Vol-253-No

@] §] ~ I~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ NORTH WEST ~ ~ ~ ~ NOORDWES ~ ~ ~ ~ EXTRAORDINARY ~ ~ PROVINCIAL GAZETTE ~ ~ ~ ~ BUITENGEWONE !§j PROVINSIALE KOERANT @j III @/ ~ §].§]~ ~ ~ ~ ~ JUNE ~ ~ Vol. 253 14 JUNIE 2010 No. 6791 ~ ~ ~ ~ L::; '!I fdIE'~ §] 2 No. 6791 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 14 JUNE 2010 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an "OK" slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender's respon sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS· INHOUD No. Page Gazette No. No. GENERAL NOTICE . ALGEMENE KENNISGEWING 184 Local Government: Municipal Structures Act (117/1998): Municipal Demarcation Board: Delimitation of municipal wards: Moses Kotane Local Municipality (NW375) . 3 6791 184 Wet op Plaaslike Regering: Munisipale Strukture (117/1998): Munisipale Afbakeningsraad: Afbakening van munisi- pale wyke: Moses Kotane Plaaslike Munisipaliteit (NW375) 11 6791 BUITENGEWONE PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 14 JUNIE 2010 No. 6791 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 184 OF 2010 MUNICIPAL DEMARCATION BOARD DELIMITATION OF MUNICIPAL WARDS IN TERMS OF THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT: MUNICIPAL STRUCTURES ACT, 1998 Municipality: Moses Kotane Local Municipality (NW375) In terms of Item 5(1) of Schedule 1 to the Local Government: Municipal Structures Act, 1998 (Act NO.117 of 1998) ("the Act") the Municipal Demarcation Board hereby publishes its delimitation of wards for the above-mentioned municipality.